The strong feelings aroused by the Heimosodat (“Kinship Wars”) are a good background to the strongly nationalist and anti-Russian feelings among a fairly large sector of the Finnish population at the time, and thus somewhat relevant to my scenario as it progresses. It’s also a major piece of Finnish history that not too many people outside of Finland have every heard of. I’m including this in some detail as a historical prelude to my alternative history scenario, where it will aid in an understanding of the “Greater Finland” viewpoint espoused by an influential portion of the Finnish population at the time of the outbreak of WW2.

The Heimosodat

Heimosodat – the Finnish Kinship Wars of 1918-1922

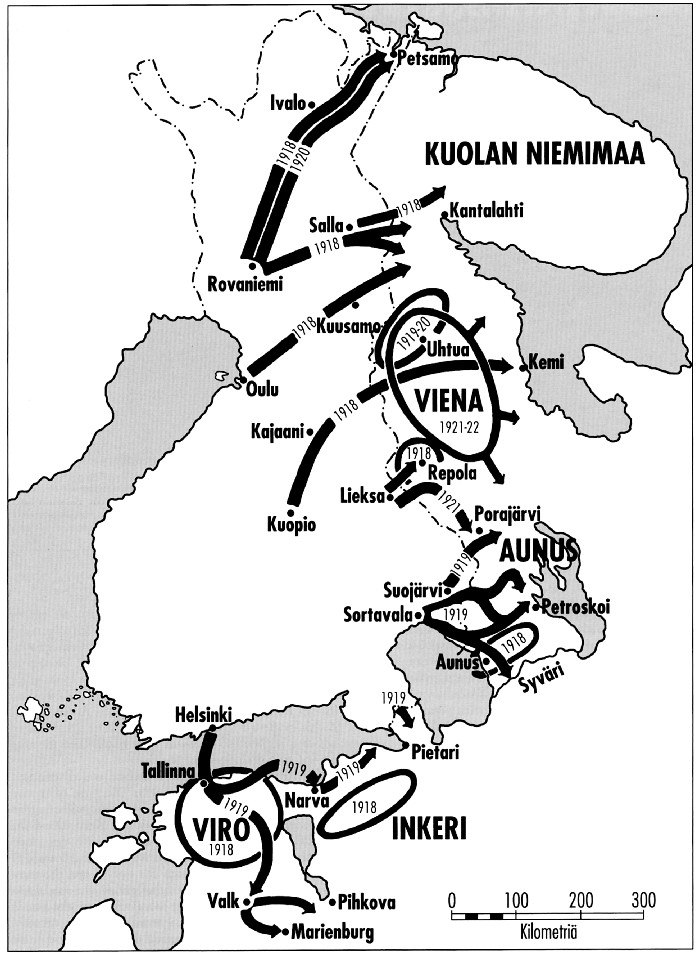

The Heimosodat, or Kinship Wars (in English literally “Kindred Nations Wars”, “Wars for Kindred Peoples” or “Kinship Wars”) were the conflicts in territories inhabited by other Finnic peoples, often in Russia or along the at that time loosely defined borders between Finland and Russia. Some 9000 Finnish volunteers took part in these wars between 1918 and 1922, with the objective of bringing under Finnish control the large areas between Finland and the White Sea with predominantly Finnic populations. Many of the volunteer soldiers were inspired by the idea of Greater Finland.

Some of the conflicts were incursions from Finland while some started as local uprisings, with the Finnish volunteers wanting either to help their kindred people in their fight for independence or to annex the areas to Finland. When Finland declared independence, a century of nationalist agitation had created a mood where Finnish politicians viewed Eastern Karelia as nationally Finnish territory that should be included in any future administrative reorganization of the Grand Duchy. A good part of the population of the former Grand Duchy of Finland also felt that they had an obligation to help other Finnic peoples to attain the same status as Finland, preferably as part of Finland itself. The Finnish Civil War had awakened a strong nationalistic feeling that sought tangible ways to make itself have an impact and in February 1918, Mannerheim, the commander of the Finnish White Army, wrote his famous “sword and scabbard” Order of the Day, in which he stated that he would not return his sword to his scabbard until East Karelia was free from Russian control. (“I will not put my sword in my scabbard before all the fortresses are in our hands, before constitutional order prevails in the country, not until the last warrior of Lenin and the last thug is deported and Finland includes White Sea Karelia … “). Finland had, incidentally, for the two next decades, a relatively high citizen participation in nationalistic activities (e.g Karelianism and Finnicization of the country and its institutions).

Sadly for those who don’t read Finnish, there is almost nothing available in English on this particular aspect of Finnish history. And while this is an Alternative History, I can assure you that everything about the Heimosodat in this and the following pages is historically accurate (with any mistakes largely due to my own flaws as a translator of Finnish source material). That said, the best source in Finnish that I have tracked down (other than fragments on various websites) is a Finnish-language book by Jussi Niinistö, Heimosotien historia 1918–1922″ (History of the Kinship Wars 1918-1922″). Finnish-language translation issues aside, this book contains a wonderful collection of photographs from the Heimosodat.

Heimosotien historia by Jussi Niinistön

This was published in 2005. If you’re looking for a copy, you can usually pick one up on this Finnish website – http://www.antikvaari.fi/ or on this one www.finlit.fi/kirjat. The author, Jussi Niinistön was born October 27, 1970 in Helsinki and is a noted Finnish war historian, a lecturer in Finnish history at the University of Helsinki and a lecturer in military history at the Finnish National Defence University. He was elected a member of the municipal council of Nurmijärvi in 2009 and was chairman of the True Finns group on the council. In 2011 he was elected to the Finnish Parliament as a True Finns representative.

Other books Niinistönhas written include “Paavo Susitaival 1896–1993. Aktivismi elämänasenteena” (Paavo Susitaival 1896-1993. A Life of Activism) , “Suomalaisia soturikohtaloita” (Finnish Warrior Destinies); “Pohjan Pojat: Kuvahistoria suomalaisen vapaaehtoisrykmentin vaiheista Viron vapaussodassa 1919” (The Boys from the North: A Picture History of the Finnish volunteer regiment in the Estonian Independence War of 1919); “Bobi Sivén – Karjalan puolesta” (Bobi Sivén – The Karelian; “Suomalaisia vapaustaistelijoita” (Finnish freedom fighters); “Lapuan Liike: Kuvahistoria kansannoususta 1929–1932″(Lapua Movement: Picture History of the uprising of 1929-1932); “Eteläpohjalaiset ja Suomen vapaustaistelu” (South Ostrobothnians and Finland’s struggle for liberation) and a number more. All in all, Niinistön has made a major contribution to recording the history of Finland’s fight for independence. As a current Member of Parliament, he is now the True Finns Party spokesman on Defence. You can read more about Jussi Niinistön here.

Greater Finland Nationalism & the origins of the Heimosodat

Greater Finland

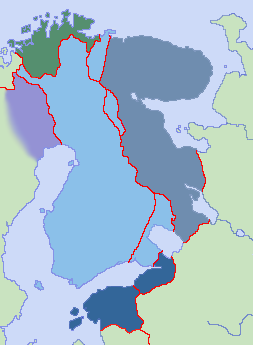

Greater Finland nationalist thinking was deeply rooted in the growing support for Finnish autonomy in the time when Finland was firmly under Tsarist Russian rule. Interest in the Finnic Karelian “tribal” people of Viena and Olonez was gradually awakened in the 1800’s as the movement of national romanticism grew in popularity along with what would become known as the “Finnish national awakening”. Interest in White Karelia also stemmed from Elias Lonrot and the Finnish Kalevala, which led many Finns to White Karelia in search of Finnish spiritual roots and wisdom. This eastern Karelian culture inspired the work of many Finnish artists, including the paintings of Akseli Gallen-Kallela, the music of Jean Sibelius and such poems as those of A. Oksanen. In the years prior to World War I, Finnish activists articulated the concept of a Greater Finland, which would free from the Russian yoke all Finnic peoples. It would also provide Finland with a safe border, the so-called “three isthmus border line” running from Lake Ladoga along the Svir River to Lake Onega and across to the White Sea, a border which could be successfully defended.

This concept was crystallized into words by Heikki Nurmio, author of the words to the famous nationalist military song, the Jääkärimarssissa, the music for which had been composed by none other than Jean Sibelius. The original words read: “Estonia, Aunus and Karelia, a beautiful country / a single great Finland.” Including Estonia within Greater Finland was considered to be somewhat excessive even by fervent nationalists, so Nurmio rewrote the words of the song into its final form, “Tavestia, Karelia, the shores and lands of Viena, one great country of Finland…”

After the October 1917 Revolution, the Bolsheviks seized power violently in Russia, overthrowing the first democratically elected government of Russia. The Bolshevik coup was followed by four years of bitter civil war between the Bolsheviks and the “Whites.” The Western Powers dispatched intervention forces to Russia, at first to help keep Russia in the war against Germany, but later to support the White forces who were fighting against the Bolsheviks. The world political situation, the chaotic civil war in Russia and the undefined Finnish-Russian border all combined to create a situation which permitted the Kinship Wars to take place.

The Government of Finland believed that taking over areas of Karelia would in the future give Finland added leverage in any negotiations to define a permanent border. The paradox was that while the integration of Eastern Karelia into Finland was the Finnish Government’s objectives, sending military expeditionary forces was not Finland’s official policy. Finland never used the Finnish Army to carry out military actions across the border. The expeditions were carried out mainly by volunteer units, although the State of Finland did provide political and some financial support. In total, the Finnish volunteers in the Kinship Wars numbered about 9,000 people so whilst they had popular support from a large proportion of the Finnish “white” population, the volunteers were limited in numbers.

The Heimosodat themselves consisted of a number of different conflicts that Finnish volunteers participated in. In broad terms, these are described as:

- The Estonian War of Independence (1918–1920) – in which the volunteer units Pohjan Pojat (“Sons of the North”) and I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko (I Finnish Volunteer Corps) helped Estonian troops in their fight for freedom.

- The Viena expedition (1918)

- The Murmansk Legion

- The Aunus expedition (1919)

- The Petsamo expeditions (1918 and 1920)

- The East Karelian Uprising (1921–1922)

- The National revolt of Ingrian Finns (1918–1920)

The Heimosodat Part 1: The Eastern Karelia uprisings, the Viena Expedition and the Aunus Expedition

Eastern Karelia – 1918

During the Finnish Civil War, the Finnish “White” forces had already begun to prepare for intervention in the wider “Greater Finland” region, looking to utilize the collapse of the Russian state to fulfill the nationalist goal of unifying the “kindred nation” of Karelians with Finland itself. At the same time, the Finnish Senate wanted to avoid direct confrontation with the various factions of the Russian Civil War, and thus refused to send the official military across the border. However, the recruitment of volunteers was not prohibited, and the Government either turned a blind eye or supported the formation of various volunteer units composed of Civil War and Suojeluskunta (Civil Guard) veterans. These volunteer units soon marched eastwards filled with nationalist zeal. The Entente Powers were not amused. Where the Finnish nationalists saw the long-waited fulfillment of their nationalist dream of a Greater Finland, Britain and France saw the aggressive expansionism of a German puppet state into a strategically important territory (the port of Murmansk & the Murmansk Railway, over which large amounts of military aid were transported to the Russian military) of their former key ally whom they were doing their best to keep in the War.

On 6th March 1918 Britain’s Royal Navy landed 130 Royal Marines in Murmansk with the tasks of guarding the local supply depots and preventing the Finnish interventionary forces from reaching and cutting the Murmansk Railway. The Entente Campaign in North Russia had begun. The original goals of this operation were ambitious, hoping to create a new anti-German resistance center in the north by providing support to local forces. As a result of these conflicting goals, Eastern Karelia would soon experience chaotic fighting over the summer of 1918. The complexities of the local political situation in Eastern Karelia are best explained by viewing the motives of various local factions and forces.

The locals themselves were Karelians, a Finnic ethnic group that largely belonged to the Russian Orthodox Church. Karelian Finns had gradually developed their own separate distinct culture with Russian influences and some key differences to Finns in a similar way the South Slavic population of Balkans gradually separated from their common origins into Serbs, Croats and Bosnians. The 19th century ethnic nationalist Fennoman movement saw East Karelia as the ancient home of Finnic culture, “uncontaminated” by both Scandinavians and Slavs. In the sparsely populated East Karelian backwoods, mainly in Vienan Karelia, Elias Lönnrot collected the folk tales that ultimately would become Finland’s national epic, the Kalevala. Conversely, most Karelians saw the Finns as “Swedes”, with an alien religion (Lutheranism) and wanted very little to do with them.

In 1918 Karelians were hungry (literally, starvation loomed) and uncertain of their political future. During the last century they had seen widespread settlement by Russian immigrants into their formerly remote home territories due the growing importance of Murmansk, and the ever closer linking of their local economy to the city of St. Petersburg. However, due to the chaos caused by the Revolution, grain supplies from the south had been cut off and the local population was threatened with starvation. Politically the Karelian local leaders would have preferred their own independence, or at least autonomy from whomever would rule Russia after the Civil War. Only some of them initially supported the idea of state union with “the Swedes”, as the locals referred to their Lutherian Finnic neighbors to the West.

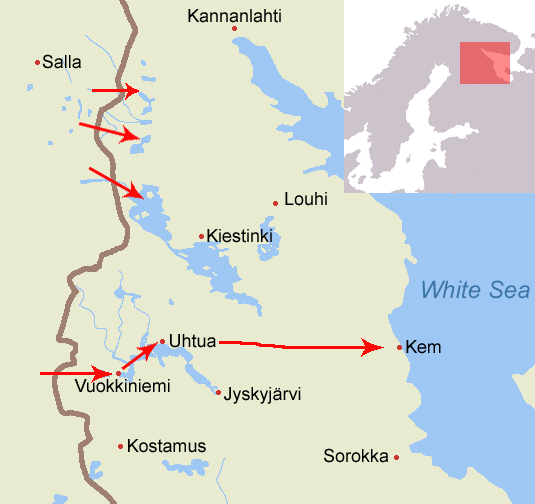

The Viena Expedition of 1918

The Viena Expedition was the first attempt by Finnish volunteer forces to annex White Karelia (Vienan Karjala). The first units of volunteers marched into Eastern Karelia in the spring of 1918, when the Finnish War of Independence (the Civil War between the Reds and the Whites) was still in progress within Finland. The military objective was essentially to secure White Finland’s flanks, although there were also nationalist objectives (indeed, the first expeditionary unit crossed the border at Suomussalmen on 21 March 1918, only four days after the start of the Civil War fighting in Tampere). The Vaasa government (the democratically elected majority “White” government against whom the Red Finns had launched their coup) had planned the offensive into Eastern Karelia as Mannerheim was concerned about the threat of the Red Finns who had fled across the loosely defined eastern border. It was stressed to the volunteers that they were not an Army of occupation, but were there to arm and assist the local population of Karelia and to combat Bolshevism. The expeditions called for Karelians to rise against their (Russian) oppressors and stressed a common Finnish language and national traditions.

Captain Toivo Kuisma

This first expeditionary unit was led by Lieutenant-Colonel C W Malm , the North Savo and Kainuu Suojeluskuntas commander. From a military family and the son of a former Russian Army cavalry captain, Malm was already a seasoned officer with combat experience. Mannerheim had refused to give his blessing to the plan if Malm was not placed in command. This was done, and Malm’s force operated directly under command of the military headquarters. Malm would lead a 350-man strong unit of volunteers from Kuopio and Savonlinna into White Sea Karelia. A second unit was led by Jaeger Captain Toivo Kuisma. These crossed the border one week after Malm’s unit. The objectives of these two units were to inspire the local Karelians to rise and fight, and to cut the Murmansk Railroad at Kem.

A third force in the North was made up of 500 Finnish Jäger volunteers, led by Lieutenant Kurt Martti Wallenius, split into four 125-man companies. The objective of Wallenius’ men was to seek out and destroy the remnants of the Finnish Red Guards who were sheltering or in hiding across the eastern border.

Major Kurt Martti Wallenius

The overall goal was to liberate White Karelia and establish the “three-Isthmus” border – a line which would follow the Svir from Lake Ladoga to Lake Onega, and thence to the White Sea. Initial operations in Northern Finland were successful and the Red Finns were forced to withdraw to Eastern Karelia. Wallenius and his light infantry crossed the border at Kuusamo after delays due to lack of equipment (they had, for example, not a single machinegun – only rifles) but got bogged down in fighting the Finnish Red Guards. The low level of training and the low morale of the conscripted troops made any advance difficult. The numbers of Bolsheviks and their weapons were also underestimates, with the volunteers suffering some casualties. Wallenius attempted further attacks but these were unsuccessful. Howver, the attacks frightened the Red Command and the defending Red Finns withdrew of their own volition. In the end the force was withdrawn back within the Finnish borders and performed only small incursions into East Karelia.

The Finnish southern Viena Expeditionary Force was at first more successful. This group was led by Lieutenant Colonel Carl Wilhelm Malm and consisted of about 350 volunteers. By 10 Apri 1918l, Malm’s group had advanced as far as the coastal town of Kem on the White Sea. Malm was unable to capture the town and retreated to Uhtua where he began defending western White Sea Karelia.

The 1918 Viena Expedition

The Finns now switched tactics and adopted a village-by-village strategy of persuading locals to join the Finnish volunteer side. When the Finnish troops arrived in White Sea Karelia they noticed that the population was divided. A part of the population wanted to secede from Russia and form an independent Karelia which would also be separate from Finland. However, a larger part of the population just wanted some form of autonomy. Many thought they would get autonomy as part of Bolshevist Russia. Only a small minority of the population wanted Karelia to be joined to the new state of Finland.

Most importantly, for the great majority of the population, practical issues (such as ensuring having enough food) were more important than ideological issues. In the end, the proposal to join East Karelia to Finland received support in the White Karelian villages around Uhtua. Local Finnish White Guard (Suojeluskunta) militias were formed in over 20 villages in that area. In July, Malm fell seriously ill and was recalled back to Finland and in his place Captain Toivo Kuisma was placed in charge of the Finnish troops. Kuisma proved a tougher commander than Malm and also was able to learn from past mistakes. He formed units of Karelian tribal people commanded by Finnish volunteers, resulting in two Infantry and one Machinegun Company being formed. Most of the Finnish volunteers in his unit were young – between 16 and 20 years old, because the Government wanted men over 21 years of age to fight in the Civil War which was raging in Finland.

By June 1918 the British/American Murmansk Expeditionary Force in Eastern Karelia was steadily growing in size due to the active work of Colonel P.J. Woods. Woods was acting more or less independently when he decided to bolster the ranks of his hodgepodge force of British-French-Polish-Serbian units by starting recruitment campaigns among the Finnish Red Guards that had withdrawn into Eastern Karelia after the Civil War and were now continuing their civil war against the Finnish volunteer military expeditions there. Woods allowed these men to enlist in his service, and by June 1918 he had over 1,500 volunteers, of whom he chose one-third to receive British military training and weapons. Even though this unit was mocked as “His Majesties Royal Bolsheviks” by many other officers of the expedition, Woods continued his recruitment efforts, this time targeting the local Karelian population, resulting in the creation of another volunteer force, the Karelian Regiment.

The situation of the Viena expedition began to deteriorate. The Karelian regiment stationed in Kem attacked the Finnish troops at Jyskyjärvi on 27 August. 18 men were lost. The next attack came against Luusalmi on 8 September when 42 Finns were killed. The following battles were fought at Kostamus and Vuokkiniemi in September-October. Soon Woods and his 4000-men strong “Irish Karelians” (Woods was of Northern Irish origin and the badge of the regiment, designed by Woods, consisting of a green shamrock on an orange field) were without question the strongest military force in the region, and the early hopes of Finnish nationalists were quickly fading away. Karelians were increasingly looking towards the Entente powers, especially Britain as the protector of their interests and the Finnish volunteer forces were unable to “rise the locals to revolt against their old Russian oppressors” as they had perhaps naively originally hoped. The Finnish Volunteer Forces had to offer little except nationalist propaganda, while the British provided bread and rifles to anyone willing to enlist to their service.

British and Soviet propaganda, as well as British food, money and arms, did their job and by Autumn, the Finnish expeditionary forces were on the retreat. The Finnish commanders requested reinforcements but Mannerheim declined to send these. The British forces under Woods were able to push the Germans and Finns established in Uhtua out of White Karelia (Vienan Karjala), with the Finnish Volunteers returning to Finland on 2 October 1918. During the retreat of the Finnish Volunteers, there was some hard fighting at Vuokkiniemi with the British backed Bolshevik Karelian forces. Infantry second lieutenant Antti Isopuo’s 50 man strong unit carried out a flank attack on a 350 strong unit of Karelians, killing 100 and taking 7 prisoners. Of the Finnish volunteers, 20 fell, including machine-gun company commander Jussi Sairo. Sairo was given a traditional Finnish warrior’s funeral – he was placed in a boat with all his equipment, the boat was filled with rocks, towed to the middle of Aijonlahtea and sunk into the depths. Even though the Finnish Volunteers were retreating, the victories of these final battles boosted morale considerably.

Woods success with the Karelians fostered unrealistic hopes of Karelian national self-determination which were ultimately unfulfilled, caught as they were between the Finns and Russians. The formation melted away as a transfer to White Russian command was attempted and Woods was evacuated in October 1919 with the rest of the British forces.

For the Finns, the Viena expedition was a defeat. The Volunteers suffered heavy losses, The British and the Bolsheviks emerged victorious and Bolshevik propaganda within Viena Karelia was successful. The primary reason for the failure of the Finnish expeditions was the British intervention, which was driven by what was seen as the strategic need to prevent then German-aligned Finland from cutting the Murmansk railroad through which military supplies were being transported to the Russian forces fighting the Germans.

The Aunus Expedition

The Aunus expedition was an attempt by Finnish volunteers to occupy parts of East Karelia in 1919. Earlier attempts in 1918 to take Petsamo and White Karelia (the Viena expedition) had failed, partly due to the passive or even hostile attitude of the Karelians. During the summer of 1918, the government of Finland received various appeals from Eastern Karelia to join the area to Finland. Over the winter of 1918-1919, a number of refugees had arrived in Finland requesting assistance and reporting that the Bolsheviks were terrorising Aunus, taking men and food by force to meet the needs of the Red Army. Now, with Finnish independence achieved and the Civil War won, defending the Eastern Finno-Karelian tribes was felt as nothing short of a duty and a responsibility.

The time was seen as opportune to send an expedition into Karelia. In Russia, there was chaos and the Bolsheviks had enemies in every direction. Estonia in the west, the White Russians under Deniken in the south and to the east, Admiral Kolchak, all with both English and French support. The fall of the Soviet government was viewed as sure to come. Also, in previous expeditions mistakes had been learned from and the end of the Civil War in Finland had freed up more troops, weapons and equipment for the expedition. People were also motivated by the spirit and success of the Finnish Volunteer units in Estonia.

Especially active were the inhabitants of the parish of Repola, which had held a vote to join Finland. The Finnish Army occupied the parish in the fall of 1918. In January 1919 a small expedition of volunteers occupied the parish of Porajärvi, but was quickly repulsed by Bolshevik forces. Porajärvi held a vote on January 7 and also voted to join Finland.

In February 1919 Mannerheim made clear to the Western powers and the White Army that Finland would attack the Bolsheviks in Saint Petersburg if it would receive material and moral support. During the same time the plans for the Aunus expedition were prepared and the Jaeger-Major Gunnar von Herzen was chosen as the commander of the troops. He thought that the expedition would succeed with a thousand Finnish volunteers, but only if the Karelians would join the fighting. Mannerheim approved the plan, but demanded that Britain also approve before it would proceed.

General Mannerheim, who had been selected as the Regent of Finland, was definitely of the opinion that Finland should act in concert with the Great Powers to take Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) with the White Russian, and with the support of the Western Allies. The Government rejected this proposal, but at the same time there was support for sending an expeditionary force into Olonets Karelia. Lieutenant Colonel Ero Gadolin was appointed to command the expeditionary force overall, with units commanded by Jaeger Majors Gunnar von Hertzen and Paavo Talvela together with infantry Captain Ragnar Nordström. Gadolin did not get along with these three, in particular, with von Hertzen, who considered himself in command.

Mannerheim approved the plans for the expeditionary force and when the White Russian General Judenits launched his attack on St Petersburg, Parliament also voted in favour of the expedition. The plan this time was to create a frontier along the three-isthmus line running Ladoga-Svir-Onega-White Sea. Plans were drawn up and equipment assembled. Volunteers were assembled and by March 1919, von Hertzen was in a position to advise Headquarters that 1,000 volunteers had come forward and that mobilisation should take place in March in preparation for Spring.

The expeditions highest ranking officers were von Hertzen and Talvela, with 132 Officers overall, the majority of whom were from the infantry. Volunteers also included the famous Ostrobothnian infantry sergeant Antti Isotalo , who put together by himself his own company of internally displaced soldiers, as well as the Pohjan Pohjat (“Boys from the North”) veteran, infantry second lieutenant Erkki Hannula , who had put together a unit of Pohjan Pohjat veterans. The expedition crossed the border on the night of April 21, 1919. Von Hertzen remembers crossing the border like this:

“When the border was crossed between Mantsilan and Rajakonnun villages, it was decided that only the officers and NCO’s would attack the Russian barracks, which were a hundred yards away on the other side of the border. This was done. We rushed toward the post, surrounded the house, threw hand grenades in the windows, and then burst in through the doors. The Russians were taken completely by surprise, they were jumping out of the windows, those who had not fallen or were not injured. We had no losses.”

Antti Isotalo ( 13 January 1895 Alahärmä – March 17, 1964 in Seinäjoki ) was a Finnish infantry lieutenant . He was a also the grandson of the famous knife fighter Antti Isotalo. His parents, Juha Isotalo and Adolfiina Ekola, were farmers. Antti Isotalo was living on his home farm in 1908, when his father was stabbed to death. He married Hilma Ritala in 1923. By his own account, he was politically a “neutral anti-Communist.”

Isotal joined the Jaeger volunteers in the Royal Prussian Jaeger 27 Battalion on October 1915. In November 1915 he was given a forged Passport and sent to Sweden and Finland to organise the recruitment of further volunteers. He spoke publicly and at youth clubs, organising the departure of dozens of volunteers to Germany. Almost arrested by Russian Gendarmes, he returned to Germany in July-August 1916 and took part in fighting on the Eastern Front with the Battalion. He was soon ordered back to special duties in Finland but after almost being arrested again, he had to return to Sweden in January 1917. He fought with the Whites in the Finnish Civil War, where he was promoted to NCO rank and where he was also wounded (in the Battle of Tampere).

After the Civil War he was on sick leave, but remained on the books in Pori Infantry Regiment 2. He resigned from the Finnish armed forces in November 1918, and then took the job of head of the Alahärmän Civil Guard early in 1919, where he helped recuit Southern Ostrobothnia men for the Estonian War of Independence volunteer units. Isotalo joined the volunteers for the Heimosodat in Finland in early spring of 1919 to take part in the fighting in East Karelia , where he served as a company commander.

At a loss for what to do with himself after returning from the Heimosodat, Isotalo moved to Australia in 1924, where he worked as a carpenter , returning to Finland in 1927. After his return, he worked as a forest supervisor , then in the South Ostrobothnia Bank Alahärmän Volt as an office supervisor from 1928 until the Bank was declared bankrupt in 1931. Isotalo participated in the extreme right-wing Lapua Movement and then the Patriotic People’s Movement activities and was involved in the Mäntsälä rebellion in 1932 as Alahärmän paramilitary leader. After the rebellion failed, he with many other nationalist officers were given“protected jobs.” Isotalo worked for Alko as the district inspector in Seinäjoki from 1932-1945, Colonel Paavo Talvela was appointed Deputy Director. Isotalo worked for Alko until his retirement in 1958.

Isotalo did not fight in the Winter War due to stomach ulcers, but did serve as Seinäjoki garrison commander. (OTL, during the Continuation War he was appointed a Lieutenant and Liaison Officer for tribal warriors in Soviet Karelia. He then was appointed Regional Commander for the district of Oulankajoki. In June 1942 Isotalo “was discharged on grounds of age.” ATL, Isotalo is appointed as a Liaison Officer for tribal warriors in Soviet Karelia in the Winter War and helps with the evacuation of Karelians into Finland at the war’s end).

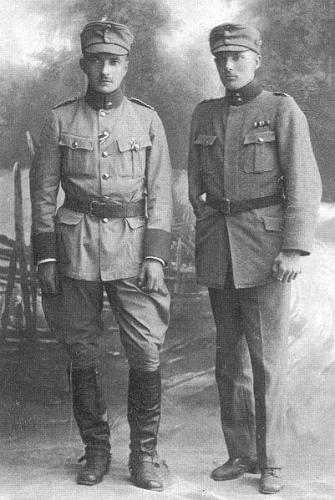

Marching to war: Captain Sihvonen and volunteers on the Olonets Expedition, the southern front in 1919

The objectives of the Expeditionary Force were to capture Lodeynoye Pole, the town of Petrozavodsk and the Murmansk railroad. The 1,000 volunteer troops were divided into three groups. Von Hertzen, led the Southern Group, targeting the railway. The group advanced rapidly. Jaeger Lieutenant Isotalo’s group had a key role in the advance: He brought is company over the ice of Lake Ladoga, completing a 120 km movement in 14 hours, and then boldly occupied the village, Isotalo himself leading the attack. Isotalo was wounded in the attack but this did not stop him riding tens of kilometers back to the main body of troops, who were in Aunuksenkaupungin, which was occupied without a fight 23 April. Von Hertzen said the city’s conquest was thanks to Isotalo’s actions.

Around this time, Gadolin resigned as overall Commander of the Expedition. The working relationship between Gadolin and von Hertzen was poor and the organisation not well defined, with the result that the forces on the ground suffered from and unclear chain of command. Mannerheim appointed Colonel Martti Sihvo as the new commander of the troops. Major von Hertzen was not quite satisfied with this, but he still got along better with Sihvo than with Gadolin. A new round of recruiting for 2000 new volunteers was also started at this time.

Talvela’s Northern Force reached the strategically important town of Prääsä on 29 April and then moved towards Petrozavodsk in pursuit of the fleeing Bolshevik units. Local Finns greeted the Finnish force joyfully, at Viel Lake many local men joined the force (the Finns had hoped that the Karelian population would have joined the troops en masse as volunteers but only a few did and their morale was never very high). Talvela’s men had now advanced 150 km from the border, their strength in numbers was insufficient to advance further against the Bolshevik forces facing them and the troops now settled into defensive positions 40 km from Petrozavodsk. To improve the defensive position, the Northern Force captured the adjacent village of Matrosen on 3 May. Seven Finnish volunteers and three aunuslaista (local aunus men fighting with the Northern Force) died in the battle, but the victory went to the Finns.

The Bolsheviks beat back the troops of the Southern Force, who were trying to move towards the Murmansk railway and Lotinapeltoon. With control of the Murmansk Railway now assured, the Red Army troops next focused on Olonets. Control of Aunuksenkaupungin by the Finnish Expeditionary force was lost on 4 May. Around 80 Finnish volunteers fell in battle and and in the retreat. The frontline was stabilised at Alavoisissa where the troops were given a rest and found time to reorganize themselves. The British troops that operated along the Murmansk railroad were quite close by, but did not participate. Talvela’s Force held its position as Prääsä, where he also made contact with the British in the hope of co-operation with the British forces in Karelia. The response was terse: although the British were in an alliance with the Russian Whites against the Bolsheviks, the British plans did not support a Greater Finland, perhaps not even an independent Finland.

Von Hertzen recaptured Aunuksenkaupungin on 7 May. He decided to continue the attack, in spite of the unstable situation and the strength of the enemy. This caused a mutiny within the Force, resulting in approximately one hundred men leaving and going back to Finland. Even Isotalo and infantry Captain Kalle Hyppökän were unhappy with the situation. The situation on the Southern Front was unstable and Aunuksenkaupunginsta had to be abandoned again on 13 May, with the troops withdrawing to form a defense line on the Tuulos River.

In late May, von Hertzen commanded 1,260 men (22 officers, 266 non-commissioned officers and 1,072 soldiers) and 948 tribal warriors. The numbers however, began to decline in late June, when the contracts with some of the men began to expire and not all wanted to renew their contracts. Talvella also had the same problem in the north, but he was able to replenish his strength with local volunteers, who were more willing to fight against the Reds.

The Finnish High Command saw the expeditionary force taking part in the future takeover of Petrograd, and pushed Sihvo to advance on and take Petrozavodsk. They wanted Finnish troops in Petrozavodsk before the British and the Russian White Guards. If the British-White Russian coalition arrived first, it would be a tough setback for the expedition, as despite having a common enemy, relations were still chilly. Reinforcements were directed to the north to Talvela, while von Hertzen was ordered to remain in position. However, von Hertzen went against orders to move his troops in the direction of Lotinajärven. At first, the Finns, under Captain Sihvonen, Sergeant Isotalo and Captain Hyppölä, proceeded quite far in triumph, Isotalo reaching Aunuksenkaupungissa.

The initiative now passed to the Bolsheviks and the Finnish advance was halted by Bolshevik forces. On June 26 over 600 Finns of the Red Officer School in Saint Petersburg made a landing at Vitele across Lake Ladoga behind the Finnish lines. Bolshevik ships were able to fire on the Finnish positions. This gunfire killed Sihvo’s Chief of Staff, Toivo Kuisma, who had just arrived in Olonets. The southern group was forced to retreat to Finland after suffering heavy losses. Major Paavo Talvela’s regiment started an attack aimed at Petrozavodsk on June 20, but was beaten by Bolsheviks and Finnish Red Guard forces just outside the town after Trotsky sent in fresh Bolshevik reinforcements. Talvela’s group was also forced to withdrew his troops to the Säämäjärvi-Munjärvi line and later to retreat back to Finland, with Finnish volunteer forces remaining only in the two border parishes of Repola and Porajärvi.

Advancing Bolshevik units forced von Hertzen to withdraw also. The Finnish government decided to do nothing and only to keep track of what was happening as they feared the Soviet reaction. This decision struck the last nail in the coffin of the expedition: reserves and equipment to support the expeditionary force were not sent. The supply lines to von Hertzen’s force were cut, and this resulted in the near collapse of the southern front. In the north, Talvela was withdrawing after knocking at the gates of Petrozavodsk.

Both von Hertzen and Nordstrom submitted their resignations. Both resignations were approved. The southern force was merged with the northern force, with a total strength of 2 243 men. Again, this force broke down in July after Talvela pulled out to take a couple of weeks holiday. Also Sihvo had resigned as Chief of Staff, but Captain Sihvonen, supported by Sergeant Isotalo, did not give up, but brought new volunteers to the frontline and a foothold was held on the former southern front. At the end of Isotalo went to Government Minister Luopajärvi to request the authority to recruit more volunteers in South Ostrobothnia. Men were gathered and Isotalo had some defensive successes in the autumn of 1919. The Olonets expedition finally withdrew on 15 January 1920, but fighting along the border areas continued for a few more months. The last Finnish soldiers returned to Finland on 11 March 1920.

The Finnish volunteers suffered almost 400 dead. Most of the killed died either in battle or in field hospitals, either due to injuries or to lack of medical care and transportation difficulties. The wounded amounted to some 600 men.Although the expedition was supported by the State, the men themselves were all volunteers, almost all from the infantry or tribal activists.The main reason for the failure of the expedition was insufficient numbers of soldiers. Major von Hertzen expressed the public opinion that if the government had sent in the army to ensure the conquered territories were defended after they had been captured, they could have been kept. The reality however was that the government left the expeditionary force to fend for themselves, and thus, with insufficient men and no heavy weapons, they failed.

The East Karelian Uprising

In the treaty of Tartu in 1920 Finland and Soviet Union agreed on their common border. Repola and Porajärvi were left on the Soviet side and the Finnish troops had to be withdrawn before February 14, 1921. During the treaty negotiations, Finland proposed a referendum in East Karelia, through which its residents could choose whether they wanted to join Finland or Soviet Russia. Due to opposition from Russia, Finland had to withdraw the initiative. In return for ceding Repola and Porajärvi back to Russia, Finland acquired Petsamo and a promise of cultural autonomy for East Karelia. However this promise of cultural autonomy was not met. The young police chief in Repola, Bobi Sivén shot himself in protest.

The East Karelian Uprising began in November 1921 and ended on March 21, 1922 with the Agreements between the governments of Soviet Russia and Finland on the inviolability of the Soviet–Finnish border. The motivation for the uprising was the East Karelians’ year long experience of the Bolshevik regime – not respecting promises of autonomy, food shortages, the Finnish nationalist “kindred activists” desire to amend the results of the “shameful peace” of Tartu, and the wishes of exiled East Karelians. Finnish kindred activists, notably Jalmari Takkinen, the deputy of Bobi Sivén, the bailiff of Repola, had been conducting a campaign in the summer of 1921 in order to rouse the East Karelians to fight against the Bolshevik belligerents of the ongoing Russian Civil War. The pivotal moment in the uprising was the council meeting of the Karelian Forest Guerrillas (Karjalan metsäsissit) in mid-October 1921. It voted in favor of secession from Soviet Russia. The key leadership was formed by military leaders: Finnish-born Jalmari Takkinen, aka. Ilmarinen, Ossippa Borissainen and Vaseli Levonen aka. Ukki Väinämöinen, who had prominent Karelian features and a general resemblance to the Finnish mythical character, Väinämöinen – and as such was deemed suitable for his role as an ideological leader.

Finnish and East Karelian soldiers figting side by side against Russians in the East Karelian uprising

Some 550 Finnish volunteers joined the uprising, acting mostly as officers and squad leaders. Most famous of them was Paavo Talvela and Erik Heinrichs, who later served as high ranking staff officer in the Winter War. The uprising is a peculiarity among the heimosodat at this time as the initiative was not taken by Finnish insurgents, but by East Karelian separatists, and Finnish government remained officially passive. The uprising began with the immediate summary execution of anyone who was or was suspected of being a Bolshevik. The uprising escalated into military engagements over October–November 1921. The 2,500 Forest Guerrillas were initially fairly successful, despite their lack of proper equipment and by the autumn of 1921 a major part of White Karelia was under their control.

The East Karelian rebels got some publicity in international media, but they had expected Finland to intervene with its defence forces. However, the Finnish government refused any official participation, but it did not prevent private Finnish volunteer activists from crossing the border. Finland also agreed to send humanitarian aid to the East Karelian rebels, taking the risk of provoking a war with the Soviet Union. Russian historians, however, stipulate that the Finnish government did support the uprising in a military manner, and was intervening in an internal conflict. In Northern White Karelia the smaller Vienan Rykmentti (Viena Regiment) was formed. On November 6, 1921 the Finnish and Karelian forces began a new incursion into East Karelia. According to Finnish historians, on that day Karelian guerrillas and Finnish volunteer forces attacked in Rukajärvi. Russian historian Alexander Shirokorad claims this force was 5,000–6,000 strong, which is twice the total strength of East Karelians and Finnish volunteers combined according to Finnish records.

Command of the Battalion in Olonets Karelia was first taken by Gustaf Svinhufvud and thereafter by Talvela, at the middle of December 1921. By the end of December 1921, the Finnish volunteers and Karelian Forest Guerrillas had advanced to the Kiestinki Suomussalmi – Rukajärvi – Paatene – Porajärvi lines. Finnish support of the uprising with volunteers and humanitarian aid caused a chill in Finnish-Russian diplomatic relations. Leon Trotsky, the commander of the Red Army, announced that he was ready to march towards Helsinki and Soviet Russian troops would strike the East Karelian rebels with a 20,000 strong army via the Murmansk railway. Meanwhile, approximately 20,000 troops of the Red Army led by Alexander Sedyakin reached Karelia and mounted a counterattack. The Red Army also had Red Finns within its ranks. These Finns had emigrated to Soviet Russia after their defeat in the Finnish Civil War.

At the onset of winter the resistance of the Forest Guerrillas collapsed under the superior numbers of the Red Army, famine, and freezing cold. The rebels panicked, and their troops started to retreat towards the Finnish border. According to Shirokorad, the troops of the Red Army had crushed the main group of the Finnish and Karelian troops by the beginning of January 1922 and had retaken Porajärvi and Repola. On January 25th 1922 the northern group of the Soviet troops had occupied Kestenga and Kokkosalmi, and by the beginning of February occupied the settlement Ukhta. During the final stages of the uprising, the Red “Pork mutiny” occurred in Finland, sparking a hope among the rebels and Finnish volunteers that this would cause the Finnish government to intervene and provide military aid to the insurgents. This did not happen; on the contrary, the minister of the Interior, Heikki Ritavuori, tightened border controls, closed the border preventing food and munitions shipments, and prohibited volunteers crossing over to join the uprising.

The assassination of Ritavuori on February 12, 1922 by a Finnish nationalist activist did not change the situation. The last unit of the uprising, remnants of Viena Regiment, fled Tiirovaara on February 16, 1922 at 10.45 am and reached the border at 1 pm. On June 1, 1922 in Helsinki, Finland and Soviet Russia signed an Agreement between the RSFSR and Finland about the measures providing the inviolability of the Soviet–Finnish border. Both parties agreed to reduce the number of border guards and to keep those who did not reside permanently in the border zone from freely crossing the border from either side to the other. Towards the end of the uprising some 30,000 East Karelian refugees evacuated to Finland.

A 1922 Bolshevik propaganda poster: “We don’t want war, but we will defend the Soviets!”

The Heimosodat – an Assessment

As has already been stated several times, the Heimosodat (Kinship Wars, or Tribal Wars) are not well known inside Finland and even less so outside of Finland, where they are virtually unknown. In point of fact, what you have read here is more than likely the best overview you’ll find that’s available in English (and I apologize for any mistakes – I’ve been translating from Finnish source material and my Finnish is poor…..so there may be some inadvertent mistakes as a result).

There are several reasons for this low profile, but chief among them is that there was never any formal war, the expeditions were treated as voluntary efforts and after their lack of success, the Finnish Government deliberately played them down and tried to keep Finland’s involvement as low profile as possible. Overall, one can safely say that the Heimosodat were a complete failure, with none of their overly ambitious aims achieved. The timing of the expeditionary forces was also not the best, with many of the Finnish Whites tied up in the fighting of the Civil War at the time of the initial incursions. This saw its reflection in many of the early expeditions being made up of ill-equipped and ill-prepared young men. At worst, such as in Wallenius’ force, there were a lot of criminals who were motivated by the pay and the chance to acquire war booty. In addition, the resistance that was encountered was tougher than expected. Neither were the local people particularly sympathetic to the Finnish cause, while the British in Murmansk gave their support to the Red Army.

The chances of success for this trip were from the very small, while it was still well-known that Valkokaartilla there was hardly any reserves to ship to Karelia. These were all factors that contributed to yet a number of successive losses, which certainly decreased men’s mood. Defeat is not given, although many purnasivat and fled. This perseverance paid off when the bad Penalty kill U.S. Department Kuisma took the victory over the Murmansk Legion Vuokkinemi the end of the trip. This victory was an indication that Finnish men are like steel: it may bend, but not break. Winning the battle to force the enemy showed that the potential of the new rides are still, as long as the design is done with great care.

The English account for tribal wars is interesting. The earlier when reading my posts, I thought that their contributions would benefit from a brief explanation: Full English was placed in Murmansk 1 during World War II. Their mission was to prevent German access to the north. For this reason, they took with the Finns together, because tribal wars, if successful, would have improved the German transport links to Russia, particularly in the Arctic Ocean äärelle Petsamo. This prevention was seen as so important that even though the Brits were in league with the White Russian, they collaborated with the Bolsheviks, including the red Murmansk Legion to stop the German north of opportunities for career advancement. The image at the chaotic situation in addition to this well by the fact that at a time when the White Russian allied with the British fought alongside the red and white against the Finnish, British warships were escorted by Finnish Estonia tribal warriors to fight against the Reds.

Estonian War of Independence was once again the success of the Finnish and display of power, and it is the part of the tribal wars, which is the highest in the history books said. I Ekström Finnish Free Mass, and Kalm’s North Boys were able to literally everything you tried, even Kalm’s own reckless attack carried out without the support came from Marienburg. This attack would be their failure could destroy not only the whole of the North Boys’ Department, the Finnish hard reputation of Estonia. Also, Ekström’s men a decisive role in the invasion and conquest of Narva, were important factors. These successes, the Finns were the seal of fraternal friendship and for that a couple of decades later, Finland, Estonia sent volunteers to assist in the Winter and Continuation War.

Lack of own troops proved to be a stumbling block for each excursion. Olonetsky trip back was all the conditions to succeed. Local assistance was guaranteed by the self-help requests under the terror of the Bolsheviks. The Civil War in Finland was over, and able men, who had gained experience in the Civil War than in Estonia in the fighting, it was possible to send the journey proper equipment. Previous trips had been learned and leadership were the best men. Although the co-Gadolin and von Hertzen between did not work, not even that hindered the men were loyal to the von Hertzen for. Also Olonetsky sleepers in the English took the now neutral position, which in itself was facilitated by the work the tribal warriors fight only against the Bolsheviks.

The trip turned out to be stumbling blocks only a few factors: first, the Finns went from victory to victory, but the Murmansk path can be obtained from the cross. When the Finnish government decided not to send additional troops, the expedition was left completely to their own devices. This is a shame, because if the Finnish army was in full support of the Olonets gone, it would have been a release of a fully realistic goal.

Pechenga first trips was finally brave and idealistic but inexperienced, and a small number of students in an adventure trip, in no time, kohdaltaan was not the best possible. The second excursion possibilities were better, but as the expedition led Wallenius said troops were again too low. The Finns, however, did a good job of dispersing the northern Red Guards, and retrograde northern conditions was no easy job. Probably without Wallenius hunter’s skills in the whole expedition would have been to return.

Karelian uprising is also a story of its own. It was a very late date, 1 World War II and the Finnish civil war in the end. Grandpa minstrel and Jalmari Takkinen, however, chose the difficult path, which might be the way to freedom from the yoke of the Bolsheviks. The company was desperate, but the Karelian peasants saw it as a better alternative than just a silent assent, and humbling.

Tribal Wars, executive forces were also a number of interesting and exemplary kansanmielisiä men, many of whom remained active for a long time after the tours. White tour manager Toivo Kuisma second was the only expedition leader, who fell during the tours. He was assigned to work in the headquarters of paper, but a fiery tribal warriors, he took part in the battles of their own accord Olonetsky, where he was killed. St. John’s Wort was buried in a tomb Antrea hero.

Kurt Martti Wallenius is a more familiar figure to Finns. He was active in the Lapua Movement and the IKL and was cited on suspicion of involvement in the group which carried out the kidnapping of President Ståhlberg (Wallenius denied involvement until his death). In the Winter War, he was one the senior officer in Lapland. Due disputes with Marshal Mannerheim, Wallenius saw no follow-up service after the Winter War. Wallenius got himself a medical certificate for military service and then joined the forces on a voluntary basis, but even in this he was not successful due to his advanced age. After the war, Wallenius lived with his wife in a hunting lodge in Rovaniemi. He died at more than 90 years old in Helsinki in 1984.

Martin Ekström and Hans Kalm, leaders of the expeditionary forces in Estonia, were from the 1930’s onwards openly National Socialists. Ekström was a Swedish Nationalsocialistika Blocket volunteer leader, as well fighting again in the Winter War. He lived for a long time in Helsinki, where he died in 1954. Kalm, while working as a Finnish National Socialist Labour activist, was after the war one of the leading Finnish homeopathic medicine doctors. Kalm was a humane man, and he wanted to compensate for the wars by working as a doctor (sotilaanahan Kalm and his men was known as a merciless fighters in the Civil War). Hans Kalm died in 1981 at the age of 92.

Thorsten Renvall, commander of the first Petsamo expedition, was an active supporter of the idea of independence, as well as a pioneer of nature conservation in Finland. He founded the Turku Society for Animal Protection and also served as one of the founders of Turun Sanomat. Renvall died in Turku in 1927.

The Olonets (Aumus) expedition generated many legends, chief among them that of Jaeger Warrant Officer Antti Isotalo. Gunnar von Hertzen and Ragnar Nordström were both active in the Lapua Movement and were IKL activists. Nordstrom also assisted in volunteer recruitment for SS-men from Finland, During the Cpntinuation War he worked in Karelia in improving the living conditions of children in the occupied territories. After the war, he was an active organizer of the aseenkätkennän (Gun Concealment – where members of the Finnish military his large quantities of weapons and ammunition so as to be able to fight any attempted takeover of Finland by the Soviet Union). Nordstrom died in Loviisa, 1984. Von Hertzen worked as a Doctor in a field hospital during the war. He died in 1973.

Ingrian uprising leader George Elfvengren was active in anti-communist activities against the Soviet Union. He was part of a group which planned to assassinate Commissar Tšitšerinin of the USSR in Geneva in 1922, but the project failed. Elfvengren then worked as a businessman in Helsinki. Details of his subsequent life are not known other than the fact that for unknown reasons, he traveled to the Soviet Union in 1925, where he was arrested. He was executed in the USSR in 1927.

Next Page: Finnish Volunteers in the Estonian War of Independance