Before I start, a note on sources: the content of this Post is largely taken from a Doctoral Thesis by ANDERS AHLBÄCK, ÅBO AKADEMI UNIVERSITY, entitled “Soldiering and the Making of Finnish Manhood: Conscription and Masculinity in Interwar Finland 1918-1939”. (see here for the source, available online). I have largely stripped out the gender/masculinity content as being superfluous to my Alternative History. However, if you’re interested, do refer to the source. Also note, all photos and associated commentary in this Post have been added by me. All of that aside, Ahlbäck has authored a magnificent historical study which is well worth reading.

At the age of 61, Lauri Mattila wrote down his memories of military training in a garrison in Helsinki forty years earlier. Mattila, a farmer from a rural municipality in Western Finland, was evidently carried away by his reminiscences, since he wrote almost 200 pages. The resulting narrative is a fascinating depiction of both the dark and the bright sides of military service in interwar Finland.1 Recalling his service in 1931–1932 from the vantage point of the early 1970’s, Mattila underlined that he had a positive attitude to the army as a young man and reported for duty “full of the eagerness of youth and military spirit”. In his memories, he marked his loyalty with “white” Finland. However, the conditions of military training he described are in many places shocking to read. He remembered recruit training as characterised not least by the insulting language of superiors: “The training style of the squad leaders was to bawl, accuse and shame the recruit. A conscripted corporal could give instructions like the following when he instructed a recruit [in close-order drill]. Lift your head, here you don’t dangle your head like an old nag. You have a stomach like a pregnant hag, pull it in. Now there I’ve got a man, who doesn’t know what is left and what is right. Tomorrow you will get yourself some litter to put in your right pocket – and hay from the stables to put in your left pocket, then you can be commanded to turn towards the litter or turn towards hay. Maybe then you will understand the commands.”

The recruits’ carefully made beds were ruined daily, “blown up” by inspecting officers, and Mattila had all the meticulously arranged equipment in his locker heaved out onto the floor because his spoon was lying “in the wrong direction.” As he moved on from recruit training to NCO training, he and the other NCO pupils were virtually persecuted by squad leaders who punished them at every step they took, incessantly making them drop to a prone position, crawl, get up again, run around the lavatories, clean the rifles, polish the squad leaders’ boots etc. The squad leaders cut the buttons of their tunics off almost daily and the pupils had to spend their evenings sewing them back on. The squad leaders could humiliate soldiers by making them kneel before them. In one instance a soldier was forced to lick a squad leader’s boot. According to Mattila, all this passed with the silent consent of the NCO school’s sadistic director, a Jäger Major. Yet Mattila also remembered training officers who were excellent educators, especially one lieutenant who always had surprises in his training programme, trained the men’s power of observation and always rewarded good achievements. The sergeant major of Mattila’s recruit training unit who had terrified the recruits on their first days of duty is later in the narrative described as a basically kind-hearted man, bellowing at the soldiers “always tongue in cheek”.

Mattila recalled his platoon’s ambition of always being the best unit in the company with apparent pride, as well as his regiment’s self-understanding of being an elite corps superior to other military units in the area. He wrote about how he acquired new acquaintances and friends during his service and how he would sit around with them in the service club, discussing “religion, patriotism, theatre, opera, we sometimes visited them (…) and yes we talked about women and it can be added that we visited them too.” After his NCO training, Mattila was assigned to be a squad leader in the main guard. He lyrically depicted the daily changing of the guard, the military band playing and the sidewalks filled with townspeople never growing tired of watching the spectacle. “Whoever has marched in that parade, will remember it with nostalgia for the rest of his life”, he wrote. As he reached the end of his long account, Lauri Mattila summed up what the military training had meant for him: “I was willing to go to [the military] and in spite of all the bullying I did not experience the army as a disagreeable compulsion, but as a duty set by the fatherland, a duty that was meaningful to fulfil. Moreover, it was a matter of honour for a Finnish man. My opinion about the mission of the armed forces and their educational significance has not changed. For this reason, I do not understand this present direction that the soldiers’ position becomes ever more civilian-like and that it becomes unclear who is in command, the soldier or the officer. The barracks must not become a resting home spoiling the inmates.”

The memories of this farmer in his old-age recount a unique individual experience. Yet they also contain many elements typical of reminiscences of military training in the interwar period: the shock of arrival in an entirely different social world; the harshness of recruit training; the complex relationships between soldiers and their superiors; the comradeship between soldiers and the perceived adventurousness of any contacts with women of their own age; the slowly ameliorating conditions as disbandment day grew closer; and the final assessment of military training as a necessary duty and its hardships as a wholesome experience for conscripts. In a sense, this Post moves on from the rhetoric of politics, hero myths and army propaganda into the “real world” of garrisons, barracks and training fields, as that world was described by “ordinary” conscripts – not only educated, middle-class politicians, officers or educationalists, but also

men of the lower classes. This however, is not to investigate what “actually happened” in military training, or what the conscripts “really experienced”, but to study the images of conscript soldiering that arose from story-telling about military training. The post studies stories about the social reality of interwar military training, both as written in the period and as memories written down decades later.

The civic education and “enlightenment” propaganda, analysed in the previous posts, powerfully propagated the notion that it was in the environment of military service that a boy or youngster was transformed and somehow reached full and real adult citizenship. The army was “a school for men” or “the place where men were made”. It was never stated in military rhetoric of the era that learning the technical use of weapons or elementary combat tactics was in itself what made men into boys. Instead, this transformation was, by implication, brought about by the shared experience of living in the military environment and coping with the demands put on the conscripts by their superiors and by the collective of military comrades. On the other hand, there was also, as we have seen, vivid and outspoken political criticism of military training within the confinements of a cadre army, as well as loud-spoken moral concerns that this same environment would damage conscripts. In this critical debate, the relationships both to superiors and to “comrades” debased the young man, the former through brutalising him and the latter through morally corrupting him. The conscripts were all exposed to the army’s “enlightenment” efforts, but it cannot be taken for granted that they subscribed to their contents any more than it can be assumed that men from a working class background espoused socialist anti-militarism. Whether they embraced or rejected the idea of military training as a place “where men were made”, it is significant in how they depicted the social relationships among men in the military and how they saw the military as changing them through the shared experience that all conscripts wnt through.

To the extent that soldiering became a crucial part of Finnish society in the interwar period, stories about what military service was“really like” conveyed messages to its audiences – and to the narrators themselves – about what it meant to be a Finn. How did army stories depict what happened as conscripts arrived for their military training? How did they describe the experience of entering the military world, with its social relationships, practices and ideological environment? How did different stories about personal experiences of military training relate to contemporary notions of soldiering? This Post emphasises how many men talked about the hardships, harshness and even brutality of military training – images of soldiering largely contradicting the pro-defence debate studied in the two previous posts. The proportion of stories about the austerity and severity of military discipline and of abuses and bullying does not prove whether this was a defining feature of Finnish military training at any particular point in time – in some conscript’s experience it was, in others’ it was not. Many men certainly had largely positive memories, emphasising good relationships with superiors, tolerable conditions and supportive comradeship. Yet even these narrators appear conscious of the powerful presence in popular culture of a “dark side” to the practices of military training that they were anxious to refute.

Perhaps one reason why the narrators – including some of those who underline that they got on well in the military and even enjoyed themselves – chose to narrate and highlight stories about forced subordination and bullying was because these stories referred to a contradiction between the actual experience of life as a conscript and the public image of the military. This derived from the tensions between relationships in the military, where the conscripts experienced the contradiction between the idea of equal citizenship inherent in a modern “citizens’ army” vs the conflicting military logic of absolute obedience. The complete and unquestioning obedience demanded in the interwar Finnish conscript army, and the oftentimes humiliating methods used to bring it about, meant a loss of control for the conscript. He was defencelessly exposed to potential abuse. This contradicted the concept of soldiers as warriors and the army as a place “where boys become men” or “where men are made”. It also contradicted the contemporary nationalist defence rhetoric of self-restraint, a sense of duty and a spirit of sacrifice, since the bullied conscript was under external compulsion, forced forward not by internal motivation but by force of violence and the threat of even worse punishments. Moreover, the relationships among the rank-and-file conscripts were run through with informal hierarchies actively upheld by the soldiers themselves. The authors Pentti Haanpää and Mika Waltari addressed this major contradiction in the army books they published around 1930 – each in his fashion.

The historicity of Experiences and Memories

Here, we will go on to analyse two groups of sources depicting experiences of military service in the interwar period; Pentti Haanpää’s Fields and Barracks (1928) and Mika Waltari’s Where Men Are Made (1931) on the one hand, and a collection of autobiographical reminiscences on the other.

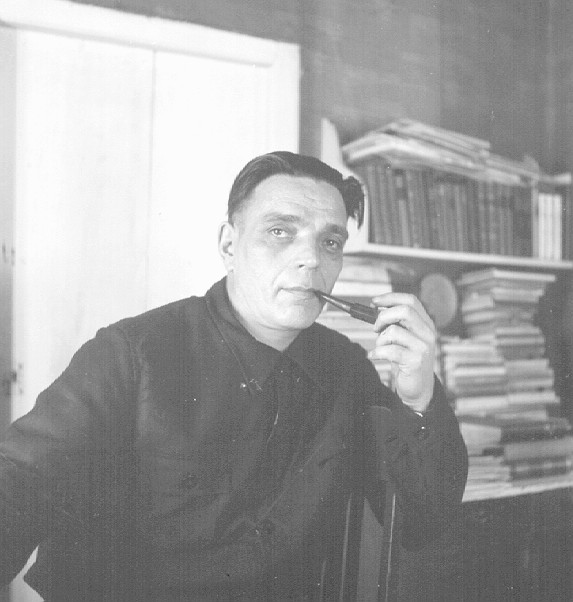

Pentti Haanpää (October 14, 1905, Pulkkila – September 30, 1955 Pyhäntä) was a Finnish novelist and a masterful short story writer

Pentti Haanpää (October 14, 1905, Pulkkila – September 30, 1955 Pyhäntä) was a Finnish novelist and a masterful short story writer whose father, Mikko Haanpää, and grandfather, Juho Haanpää, who was a senator, were also published authors. They were both socially and politically active in their home region.His mother, Maria Susanna (Keckman) Haanpää, was born in Haapavesi and came from a farming family. At school in Leskelä, Haanpää was a good student. After finishing elementary school, he began to contribute from 1921 on to the magazine Pääskynen, At the same time, he was also very active in sports. In 1923 Haanpää joined the literary association Nuoren Voiman Liitto and continued to write for its magazine Nuori Voima. Haanpää’s first book, MAANTIETÄ PITKIN (1925), appeared when he was 20. It was well received by critics, who made special note of Haanpää’s skillful use of language. A few years later the story was translated into Swedish under the title “Hemfolk och Strykare”. After this successful debut, Haanpää decided to devote himself entirely to writing.

He served in the army from 1925-26 and in 1927 published TUULI KÄY HEIDÄN YLITSEEN, a collection of short stories. It was followed by KENTTÄ JA KASARMI (1928), which portrayed the army as a closed system, working under its own rules. In the promilitary atmosphere of the time, the book generated heated discussion. Among the critics was Olavi Paavolainen, the spiritual leader of the new generation of writers, who had reviewed Haanpää’s earlier debut novel positively, and praised his straightforward and self-assured expression. Kenttä Ja Kasarmi was the first work in which Haanpää drew on his own unpleasant experiences in the army. Unable to adjust himself to military life, he felt that he had wasted a year of his life in “the straitjacket of a soldier.” Haanpää’s description of the brutal training methods and ugliness of the authoritarian military system upset patriotic reviewers so that for the next seven years no publisher would touch Haanpää’s manuscripts.

Haanpää became best known for two controversial books that he wrote during this period of enforced silence. The first of these was the socialistically orientated “Noitaympyr” (1931) in which he examined the conflict between a misfit and his unbearable surroundings. At the end of the story Pate Teikka, the protagonist, chooses Communism instead of Western democracy and leaves Finland for an unknown future – he walks over the border into the Soviet Union. The second was “Vääpeli Sadon Tapaus” (1935), a bitter criticism of army life and brutality, dealing with the sadism of petty authority. The central characters are Simo Kärnä, a recruit and later corporal, and the psychopathic sergeant-major Sato, the embodiment of sadistic militarism. After repeated humiliations, Kärnä uses his intelligence and Sato’s wife to gain his revenge, but eventually realizes that he has been as brutal as his enemy. Haanpää’s other published works from the 1930s include ISÄNNÄT JA ISÄNTIEN VARJOT (1935), TAIVALVAARAN NÄYTTELJÄ (1938), and IHMISELON KARVAS IHANUUS (1939). Isännät ja isäntien varjot was published by Kirjailijain Kustannusliike, founded by Erkki Vala. The company was closely associated with the literary group Kiila (Wedge), whose members favored radical free verse and were more or less Marxists. Haanpää was among Kiila’s best-known writers, along with such names as Arvo Turtiainen, Katri Vala, Viljo Kajava, and Elvi Sinervo. Suffice it to say that his anti-militarism and Marxist leanings in the 1920s and 1930s were not received with enthusiasm by right wing critics. Haanpää created his literary reputation chiefly with his short stories, of which he published twelve collections.

During the Winter War (1939-40), Haanpää served in the army. He was in the front line in Lapland. In 1940 while on leave he married Aili Karjalainen, a dairymaid whom he had met in the late 1930s. Haanpää utilized his war experiences in the story ‘Sallimuksen Sormi’, in which an exhausted infantry company, quartered in a church, is attacked by enemy aircraft. In the Continuation War (1941-44) Haanpää served in the service troops in the Kiestinki and Untua area. Haanpää’s war novel KORPISOTAA (1940) was translated into French under the title Guerre Dans le Désert Blanc by M. Aurelien Sauvageot. The Austrian publishing company Karl H. Bischoff Verlag also planned to translate the work; one of Haanpää’s short stories, ‘Siipirikko’, had already appeared in the German magazine Das Reich. However, German publishers did not consider Korpisotaa positive enough for the war effort. NYKYAIKAA (1942), a collection of short stories, reflected Haanpää’s bitterness and disillusionment.

After the wars Haanpää wrote some of his best works, among them YHDEKSÄN MIEHEN SAAPPAAT (1945), a war novel, in which the same pair of boots passes from one trooper to another, and JAUHOT (1949), based on a historical event when peasants seized a government granary during the great famine of 1867-68. Haanpää’s journey in 1953 to China with a delegation of Finnish writers inspired KIINALAISET JUTUT (1954). Although Haanpää had earlier condemned restrictions on free speech in the Soviet Union, he kept silent on this matter in his book on China, expressing an admiration for the spirit of change which had seized the country. “Kiinanmaassa tuoksahti joku merkillinen muuttumisen, uudistumisen ja kasvamisen ihme. Se oli jotakin ainutlaatuista ja muukalainen ei hevillä saane siitä täyttä käsitystä. Aavisteli, että kiinalaiset itse ällistelivät muuttuvaa maataan ja muuttuvaa elämäänsä ja kutsuivat siitä syystä ihmisiä maapallon toiselta puolelta näkemään, mitä heille tapahtui…” (from Kiinalaiset jutut). ATOMINTUTKIJA (1950) received good reviews by the right-wing columnist and critic Kauko Kare in the journal Suomalainen Suomi. Haanpää drowned on a fishing trip on September 30, 1955, two weeks before his 50th birthday. His last novel, PUUT, a story of a socialist who becomes a non-socialist, was left unfinished. Haanpää’s collected works appeared in 1956 (10 vols.), and then in 1976 (8 vols.). Haanpää’s notes from 1925 to 1939 were published in 1976 under the title MUISTIINMERKINTÖJÄ. Taivalvaaran näyttelijä was reprinted in 1997. ‘Haanpää monument’ (1996), made by the sculptor Tapio Junno, is situated in Leskelä, Piippola.

Mika Waltari (1908 – 1979) was born in Helsinki and lost his father, a Lutheran pastor, at the age of five. As a boy, he witnessed the Finnish Civil War in Helsinki. Later he enrolled in the University of Helsinki as a theology student, following his mother’s wishes, but soon abandoned theology in favour of philosophy, aesthetics and literature, graduating in 1929. While studying, he contributed to various magazines, wrote poetry and stories and had his first book published in 1925 (at the age of 17). In 1927 he went to Paris where he wrote his first major novel Suuri Illusioni (‘The Grand Illusion’), a story of bohemian life. Waltari also was, for a while, a member of the liberal literary movement Tulenkantajat, though his political and social views later turned conservative. He was married in 1931 and had a daughter, Satu, who also became a writer.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Waltari worked as a journalist and critic, writing for a number of newspapers and magazines and travelling widely in Europe. He was Editor for the magazine Suomen Kuvalehti. At the same time, he kept writing books in many genres, moving easily from one literary field to another. He participated, and often succeeded, in literary competitions to prove the quality of his work to critics. One of these competitions gave rise to one of his most popular characters, Inspector Palmu, a gruff detective of the Helsinki police department, who starred in three mystery novels, all of which were filmed (a fourth one was made without Waltari involved). Waltari also scripted the popular cartoon Kieku ja Kaiku and wrote Aiotko Kirjailijaksi, a guidebook for aspiring writers that influenced many younger writers such as Kalle Päätalo.

During the Winter War (1939–1940) and the Continuation War (1941–1944), Waltari worked in the government information center, placing his literary skills at the service of the government to produce political propaganda. 1945 saw the publication of Waltari’s first and most successful historical novel, The Egyptian. The book became an international bestseller, serving as the basis of the 1954 Hollywood movie of the same name. Waltari wrote seven more historical novels, placed in various ancient cultures, among others The Dark Angel, set during the Fall of Constantinople in 1453. Waltari was one of the most prolific Finnish writers. He wrote at least 29 novels, 15 novellas, 6 collections of stories or fairy-tales, 6 collections of poetry and 26 plays, as well as screenplays, radioplays, non-fiction, translations, and hundreds of reviews and articles. Internationally he is probably the best-known Finnish writer, with his works translated into more than 40 languages.

Haanpää and Waltari wrote their army books during or immediately after they went through military training, whereas the autobiographical stories were written down much later, in response to an ethnological collection of memories of military training carried out in 1972–1973. The two books are the testimonies of only two single individuals, but immediately reached large national audiences and thus made the images they conveyed available for others to re-use, confirm or criticise. The collections of reminiscences, on the other hand, contains the stories of hundreds of former soldiers, most of whom probably never published a story or took part in public debate. These sources are compared and contrasted in this Post in order to bring out both their similarities and differences and to discuss how the narrators’ class, age, and political outlook informed depictions of the actual experience of interwar military training. Both the literary works and the reminiscences are, however, highly complicated historical sources in terms of what they actually carry information about. When, how, and why they were written is essential for what stories they tell and for how they craft experiences and memories into stories. They are shaped by cultural notions, political issues, and the historically changing contents of individual and collective commemoration. It is therefore necessary to discuss the circumstances in which these sources were created, and the problems of source criticism associated with them, before entering their narrative world.

Two Authors, Two Worlds

Pentti Haanpää’s collection of short stories, Kenttä Ja Kasarmi: Kertomuksia Tasavallan Armeijasta (Fields and Barracks: Tales from the Republic’s Army, 1928), and Mika Waltari’s Siellä Missä Miehiä Tehdään (Where Men Are Made, 1931) are the best-known and most widely read literary works of the interwar period depicting the life of conscripts’ doing their military service. In addition to these two books, only a few short stories and causerie-like military farces on the subject were published in the period. Three motion pictures about the conscript army were also produced 1929–1934. These films were made in close cooperation between the film company and the armed forces. The images of soldiering they conveyed was of a similar kind to those in military propaganda materials such as Suomen Sotilas. The films became a success with the public and were followed by no less than four military farces, premiering in cinemas in 1938–1939. The first feature film about the conscript army, ‘Our Boys’ (Meidän Poikamme, 1929), was released in the wake of Fields and Barracks. The film was first advertised as both more objective and truthful, and later as more patriotic in its supportive attitude to the armed forces and a strong national defence than Fields and Barracks – which demonstrates the impact of Haanpää’s work.

Pentti Haanpää (1905–1955) was born into a family of “educated peasants” in rural Northern Finland. His grandfather had been a representative of the peasantry (rural smallholders) in the Finnish Diet in the nineteenth century and was the author of books of moral tales. His father and two uncles were also both politically active in their local community and amateur writers. Yet Haanpää did not go through any higher education as a young man. He took occasional employment in farming and forestry and went on living on his family’s farm far into adult age. When he made his literary debut in 1925, the cultural establishment in Helsinki greeted him as a ‘man of nature’; a lumberjack and log rafter from the deep forests; a narrator brought forth from the depths of the true Finnish folk soul. His three first books received enthusiastic reviews in 1925–1927 and critics labelled him the new hope of national literature. All this only made the shock the greater for the nationalist and bourgeois-minded cultural establishment when Haanpää published Fields and Barracks in November 1928.

Haanpää had done his military service in the “wilderness garrison” of Kivimäki on the Karelian Isthmus, close to the Russian border, in 1925-1926. Since he lacked formal academic education, he served in the rank-and-file. During his time in the Kivimäki garrison, he developed a deeply felt indignation towards the army’s educational methods. He wrote the short stories of Fields and Barracks during the year after his completion of conscript service. They were fictional stories, but set in the contemporary Finnish conscript army and written in a style combining expressionism with psychological realism. They depicted military life as a time of gruesome hardships, sadism and violence that appeared meaningless to the conscripts and frustrated officers to the point of desperation. Haanpää’s regular publishers considered some sections portraying the soldiers’ uninhibited joking and partying so indecent that they wanted them to be left out. Haanpää refused to make even minor omissions and took his manuscript to a small socialist publishing house, which published it unaltered. The book aroused great controversy in Finland in the autumn of 1928 because of its hostility to both the military training system and the official pro-defence rhetoric. It was discussed in editorials as well as book reviews. There were demands for all copies to be confiscated and many bookshops did not dare put the book openly at display. The book was nevertheless a small commercial success – four new editions were swiftly printed. Yet Haanpää became an outcast in the mainstream cultural scene for several years.

Mika Waltari (1908–1979) was born into a family of priests and public servants. According to his memoirs, a Christian, bourgeois and patriotic “white” spirit permeated his childhood home. He attended an elite school for the sons of the Finnish-nationalist bourgeoisie, the Finnish Lyceum ‘Norssi’ in Helsinki, and was a member of the YMCA and the Christian Students’ Association. He emerged as a prolific author from age 17 and published several novels and collections of short stories and poems between 1926–1930. Entering the University of Helsinki as a student of theology, he switched to the science of religion and literary studies after three terms. He socialised in young artists’ circles, most importantly the famous ‘Torch Bearers’ (Tulenkantajat) group that combined Finnish nationalism with internationalism and optimistic modernism. The great success of his bestselling first novel, ‘The Great Illusion’ (Suuri Illusiooni) in 1928 helped him take the leap of giving up his plans to become a priest and committing himself to a writer’s career.

Waltari partly wrote Where Men Are Made, which is almost in the form of a diary, during his military service. In the book, he actually depicted how he managed to get access to the company office’s typewriter and an allowance to write on his manuscripts during his recruit training. Where Men Are Made is literary reportage, written from Waltari’s first person perspective, describing his everyday life as a conscript in a very positive tenor. Published only two years after the scandal surrounding Haanpää’s work, Waltari’s army book was received and read as a response to Fields and the Barracks. It is nonetheless important to keep in mind that Haanpää’s was not the only negative depiction of army life in circulation after the fierce anti-militarist campaigns of 1917. Waltari’s book probably would have been written even if Haanpää had never published his. The press reactions it received were, however, muted in comparison to the furore around Fields and Barracks; it was greeted with satisfaction by some of Haanpää’s critics, but not celebrated as a major literary work.

Both Haanpää and Waltari obviously wanted to have an impact on how the Finnish public conceived of the conscript army. Yet Fields and Barracks and Where Men Are Made are also works of art, intended to convey aesthetic impressions, ideological messages, and and understanding of human feelings and motives. One might ask to what extent they may be said to mirror the attitudes and understandings of larger groups rather than only the original and imaginative vision of two artistic individuals. All that aside, Haanpää’s and Waltari’s army depictions are valuable sources to the cultural imagery surrounding conscription in the interwar period. In their books there are echoes of contemporary opinion and views about class, conscription, military training and the cadre army, which are familiar from the materials examined in previous Posts. Although Haanpää and Waltari were talented writers, they also had to make sense of what they experienced in the military through relating it to previous cultural knowledge. Their works were products of the creative imagination, yet no doubt were influenced by the forms and contents of stories about army life and political debates over conscription they had themselves heard and read. Their stories, in turn, provided frames of reference for their readers’ subsequent stories about military training; models for emplotment and evaluation to either embrace or reject.

Memories of Military Training

The collection of autobiographical reminiscences, which is studied in this Post parallel with Haanpää’s and Waltari’s literary depictions, resulted from a writing competition arranged by the Ethnology Department at the University of Turku in 1972–1973. Conscripts into the armed forces of independent Finland were asked to write down and send in their memories of military training in the peacetime army. In addition to using the department’s network of regular informants, the competition was advertised in a brochure about voluntary defence work that was distributed to every household in Finland in the autumn of 1972. The 10 best contributions would be rewarded and the first prize was an award of 500 marks (equivalent to about 500 Euros at present). Those who entered their names for the collection were sent a very detailed questionnaire by mail. The response was unusually strong for an inquiry of this kind. The Ethnology Department received almost 700 answers, which altogether comprised almost 30 000 pages (A5), both handwritten and typed. Many men who had served in the Army evidently felt a great desire to recount their army memories.

However, the accounts of military training they wrote probably tell us more about how old men in the 1970’s made sense of experiences in their youth than about how they might have articulated those experiences at the time. As historians using interviews with contemporary witnesses have increasingly stressed since the late 1970’s, oral testimony – what people tell an interviewer about their memories, or equally what they write down from memory in response to a questionnaire – cannot be read as direct evidence of factual events or even the “original” subjective experiences of those events. Experiences and memories are marked by historicity: they are dynamic and changing. Memories are fleeting and fragmentary and only take solid form as mental images or articulated stories in a specific act of recollection that always takes place in the present. What an individual considers it relevant to remember, in the sense of telling others about his or her past, changes over time. How an individual experiences military training when he is in the midst of it, how he talks about it when just returned to civilian life, and how he remembers it as an old man, can produce three very different stories. More than a source of history, these reminiscences are a kind of history writing in themselves, where contemporary witnesses become their own historians, constructing and narrating their own version of history.

Academic oral history since the 1980’s, writes Ronald J. Grele, has been “predicated upon the proposition that oral history, while it does tell us about how people lived in the past, also, and maybe more importantly, tells us about how the past lives on into and informs the present”. The author’s original reason for using the collection of reminiscences from the 1970’s was a desire to grasp what “ordinary” men without higher education told friends and family about their own experiences of conscripted soldiering. He wanted to contrast the images of soldiering in the political sphere, military propaganda, and the “high culture” of literary works by esteemed authors to the “low culture” of popular oral culture. However, this oral culture has not been recorded in contemporary sources. It can be very faintly discerned in press reports and parliamentary debates on the scandalous treatment of conscripts outlined in an earlier Post. Some of its elements can be guessed at from criticisms of “old-fashioned” training methods in storys on military philosophy, the rhetoric of civic education directed at soldiers, or the literary imagery produced by Mika Waltari and Pentti Haanpää. As such, however, the auhor estimated that no other available corpus of sources bears witness to it more closely than the 1972–1973 collection of memories, which is very comprehensive and multifaceted. It contains the stories of hundreds of men from the lower classes, whose voices are not present in the written historical sources from the interwar period. Almost 300 of the answers entered for the writing competition depicted military training in the interwar period. The author of these thesis (Anders Ahlack) used a sample of 56 stories, comprising 4213 pages, including a random sample as well as all the stories exceeding 100 pages, because of their relative richness of detail. The sample was made only among those men who had served in the infantry, since this was by far the largest branch of the armed forces and overwhelmingly dominated the public image of “the army”. Among the authors in the sample are twelve farmers, nine workers in industry, crafts and forestry (three carpenters, two masons, an engine-man, a sheet metal worker, a sawmill worker and a lumberjack), and four men who worked or had worked in the service sector (two office clerks, a policeman and an engine driver). Five men obviously had had a higher education, although this was not asked in the questionnaire, as they stated folk school teacher (2), agronomist (2) or bank manager to be their occupation. Five further men were or had been in managerial positions that did not necessarily require higher education: a district headman at a sawmill, a head of a department (unspecified), a shop manager and a stores manager. Four had been regular officers or non-commissioned officers. Twelve men did not state their occupation.

Researchers of memory knowledge within folklore studies and oral history greatly emphasise the specific situation where experiences and memories are articulated into stories. The Finnish folklorist Jyrki Pöysä points out that a “collection” of reminiscences never actually consists in gathering something pre-existing that is “out there”, waiting for the researcher to come and collect it. Instead, it is a creative activity, where memories, stories and folklore are produced in cooperation between the informants and the scholars. The questions asked, and how they are put, make the informant intuitively feel that certain stories are expected of him and he thus may recall only certain things in memory and not others. The 1972-73 collection of memories of military training was executed in a manner that signalled approval and appreciation of conscription and the Finnish armed forces. The brochure that was the main advertising channel for the writing competition propagated voluntary civic work for supporting national defence. The ingress of the questionnaire connected the history of universal conscription and the national armed forces with “over fifty years of Finnish independence”. It further claimed that “every Finnish man has learnt the art of defending the country” in those forces, thus recycling old phrases from nationalist defence rhetoric. It was also pointed out in the first section that the collection of reminiscences was realised in “collaboration with the General Staff”. All this might have influenced who participated in the collection and who shunned it, as well as the informants’ notions of what kind of narration was expected of them.

Juha Mälkki, who has worked with all the answers from the interwar period surmises that the informants might represent mainly those with positive attitudes to the army. It is impossible to know which voices might be missing, yet in the author’s opinion the collected material offers a broad spectrum of experiences and attitudes, including significant numbers of very negative images of military service. The questionnaire, worked out by the ethnologists at the University of Turku, contained almost 230 different questions, grouped under 40 numbered topics, ranging from material culture, such as clothing, food and buildings, to military folklore, in the form of jokes and marching songs, and to the relationships between men and officers and among the soldiers themselves. The meticulous list of questions was evidently based on a very detailed and specific pre-understanding of the social ”morphology” of military life; notions of how military life is organised and structured and what social and cultural phenomena are specific to it. For example, regarding leaves of absence the questionnaire asked: “What false reasons were used when applying for leaves, or what stories were told about such attempts? Was it difficult to actually obtain leave when there was a real need, or were there suspicions that the reasons were falsified? What kinds of men were the most skilled in getting leave?” The questions asked were ways of helping the informants remember, but directed their recollections towards certain topics, excluding others. Many informants wrote at length about the first questions in the questionnaire, but further on answered more briefly and started skipping questions, apparently exhausted by the long list of questions and the cumbersomeness of writing. On the other hand, several informants chose to tell “their story”, largely ignoring the questions asked.

The ensuing stories have to be read with sensitivity as to how they are written in response to specific questions, at particular stages in their authors’ lives, and in a particular historical situation. The Finnish men writing for the collection in 1972–1973 were born into, grew up, and did their military service in the same mental and political landscape as Mika Waltari and Pentti Haanpää. Yet by the time they wrote down their memories of military training they had also experienced a world war and Finland’s military defeat in 1944, which against all odds secured Finland’s survival as an independent nation. They had heard the resurgent Finnish communists criticise the interwar period as one of Finnish militarism and characterize the Finnish war efforts as aggression. They had witnessed the official pact of “friendship and mutual assistance” between Finland and their former foe, the Soviet Union. They had recently observed the emergence of a youth revolt in the 1960’s with its anti-authoritarianism and critical stance towards the nationalist and moral values of previous generations. All of this was present in their “space of experience”, illuminating and giving new meanings to their own experiences of military training as conscripts. Individual memories overlap and connect with other people’s memories and images of the past, shared by larger collectives, such as generations or nations. This can provide social support for individual memories, increasing their coherence and credibility through linguistic interaction with other people. It can also, however, result in people confusing their own personal memories with things that happened to other people that they have only heard or read about. Historian Christof Dejung points out how the informants he interviewed about their memories of the Second World War in Switzerland had re-interpreted, re-shaped and rearticulated their memories since the war under the influence of political debates on Swiss history, stories they had been told, books about the war years they had read, and films they had seen. Individual memories, Dejung summarises, are parts of collective patterns of interpretation that originate both in the past and the present.

The oral historian Alistair Thomson stresses the psychological motives at work in the process where memories are constructed and articulated. People compose or construct memories using the public languages and meanings of their culture, but they do it in such a way as to help them feel relatively comfortable with their lives and identities. In Thomson’s words, we want to remember the past in a way that gives us “a feeling of composure” and ensures that our memories fit with what is publicly acceptable. When we remember, we seek the affirmation and recognition of others for our memories and our personal identities. Still, the thesis’ author finds that a radical scepticism regarding memories as evidence of the past would be an erroneous conclusion. As many oral historians have pointed out, distortions due to distance from events, class bias and ideology, as well as uncertainty regarding the absolute accuracy of factual evidence are not unique to oral evidence or reminiscences, but characteristic of many historical sources. For example, court records are based on oral testimony that has often been re-articulated and summarised by the recording clerks. Newspaper reports are usually based on the oral testimony of interviewed people that has been evaluated, condensed and re-narrated by journalists. The historian always has to make a critical assessment of his sources in the light of other sources as well as theories and assumptions about human motives and behaviour. In this respect, memories are not different in kind from most other historical source materials. The literary historian Alessandro Portelli, famous for his oral history work, writes that oral sources tell us less about events than about their meaning, about how events were understood and experienced and what role they came to play in the informant’s life. Still, he underlines that the reminiscences told by people in oral history interviews often reveal unknown events or unknown aspects of known events. They always cast light on the everyday life of the lower, “non-hegemonic” social classes that have left few traces in public archives. Oral sources might compensate chronological distance with much closer personal involvement. Portelli claims that in his experience, narrators are often capable of reconstructing their past attitudes even when they no longer coincide with present ones. They are able to make a distinction between past and present self and to objectify the past self as other than the present one.

Neither can memories be held as the product of the interview situation alone. The oral historian Luisa Passerini points out that when someone is asked for his or her life-story, this person’s memory draws on pre-existing storylines and ways of telling stories, even if these are in part modified by the circumstances. According to the oral historian Paul Thompson, the encapsulation of earlier attitudes in a story is a protection, which makes them less likely to represent a recent reformulation. Recurrent story telling can thus preserve memories, but if there is a strong “public memory” of the events in question, it can also distort personal recollections. In interviews with Australian veterans from the First World War, conducted in the 1980’s, Alistair Thomson found that memories of the post-war period, that had rarely been the focus of conversation and storytelling, seemed more fresh and less influenced by public accounts than the stories about the war years. Thomson connects this with the powerful presence in Australian culture of an “official”, nationalist commemoration of the Australian war experience. He describes a process where the diverse and even contradictory experiences of Australians at war were narrated through a public war legend, a compelling narrative that smoothed the sharp edges of individual experiences and constructed a homogenous veteran identity defined in terms of national ideals. Nonetheless, Thomson found that oral testimony collected in the 1980’s still indicated the variety of the Australian veterans’ experiences. Many of the veterans Thomson interviewed had preserved a distance from the nationalist myths about the war experience. The influence of the public legend depended on each veteran’s original experience of the war, on the ways he had previously composed his war remembering, and on the social and emotional constory of old age. In the case of the Swiss commeration of the Second World War, Christof Dejung points out that in spite of strong national myths about the defence of Switzerland, the political left, women, and the Jewish community have maintained diverging memory cultures that were ignored in official commemoration until recently. In the final analysis, Alistair Thomson concludes from his study that there is plentiful evidence in oral testimony to make for histories representing the range and complexity of Australian experiences of war. The use of soldier’s testimony should, however, be sensitive to the ways in which such testimony is articulated in relation to public stories and personal identities.

I think we can assume that certain parts of the memories of militarytraining in the Finnish conscript army were formed and influenced by decades of the informants telling and listening to army stories together with other men. Many of their elements have probably been told and retold many times since the interwar period. An informant might be prone to include a story that has been successful with his previous audiences – comrades, colleagues, and family members – in his answer to the writing competition. Just as Haanpää and Waltari were using and commenting on contemporary popular traditions and political debates, the men composing their memories in the 1970’s certainly borrowed elements and narrative forms from literary and oral traditions in depicting military life. However, comparisons with the critical press reports and parliamentary debates on the treatment of conscripts as well as with Pentti Haanpää’s and Mika Waltari’s army books, reveal that essential narrative elements in their reminiscences were already in public circulation in the interwar period. In comparison to the cultural images of the Finnish front-line experience in the Second World War, there was by far no such equally powerful “official” commemoration or nationalist legend about interwar military training in post-war society, prescribing how one was supposed to remember it. However, historian Juha Mälkki assumes that the experiences of fighting the Second World War were formative for how pre-war military training was remembered and narrated. Mälkki has used the 1972–1973 collection for a study of the emergence of the particular military culture making possible Finland’s relatively successful defence against the Soviet Union in 1939–1940. He reckons that the informants’ notions of which military skills and modes of functioning turned out useful or even life-saving in the Winter War informed their evaluation of their peacetime military training, which was in retrospect seen essentially as a preparation for the war experience.

This is an important observation. However, we must not presume that the informants’ war experiences had a uniform impact on all of them. The thesis’ author finds significant and wants to stress not only the similarities, but also the differences among the different voices and stories in the collection. The ways experiences are articulated are never completely determined by culture, public memory or even personal history. There are always different and mutually contradictory models of interpretation circulating in a culture. Despite their elements of collective tradition, the variation among the memories display how conscripts were influenced by their varying sociocultural backgrounds and political stances, both in how they experienced military training in their youth and in how they reproduced or re-assessed their experiences during their later lives. It also bears witness to how not only self-reflection, but also factors as difficult to capture as what we call personality, temperament and genuine innovativeness make human experience richer and more unpredictable than any social theory can fully fathom.

Functionalism versus Meaning in an understanding of Bullying

To some extent, sociological interpretations of military bullying as ‘breaking down and re-building’ the soldier can be applied to the Finnish interwar case. Recruit training, with its emphasis on close-order drill and indoor duties, was evidently aimed at drilling the soldiers into instinctive, unquestioning and instantaneous obedience. According to Juha Mälkki, Finnish military thinking in the 1920’s understood military discipline as the exact and mechanical fulfilment of given orders. Inspections by high ranking officers focused on inspecting the soldiers marching past in close-order and the neatness of garrisons and camps. The outer appearance of the troops was taken as evidence of how disciplined they were, which in turn was understood as a direct indicator of how well they would perform in combat, i.e. how well they would execute given orders. However, the incessant inspections, where nothing was ever good enough, perfectly made beds were “blasted” and laboriously cleaned rifles “burnt”, also seem to have been intended to instil the soldiers with a sense that not even their utmost efforts were ever enough to fulfil military requirements. Not only should the soldiers feel that they were constantly supervised and that even the slightest infringements of regulations – a lump of sugar in the drinking cup, the spoon lying in the wrong direction – would be detected and punished by their superiors. They should also feel they were good-for-nothings who only by subjecting themselves to thorough and prolonged training by their superiors might one day reach the status of real soldiers.

In the Finnish case, there does not seem to have been any centrally controlled system or articulated plan behind this particular way of socializing the conscripts into a specific military behaviour and attitude, nor behind its extreme forms, the bullying by superiors. Rather, abuses and bullying occurred where superior officers turned a blind eye, and was easily weeded out where commanding officers wanted to stop it. The hierarchical relationships therefore varied from company to company. The rather poorly organised armed forces of the early 1920’s had to manage with NCOs and training officers without proper military education. There was a lack in the supervision of how conscripts were treated. Many officers certainly also seem to have harboured a mindset, perhaps shaped by old European military traditions, according to which scaring, humiliating and bullying the soldiers into fearful obedience was a natural and necessary part of shaping a civilian into a soldier. In addition to the military imperative of producing obedient and efficient soldiers, many officers embraced the political project of rebuilding the conscript into “a citizen conscious of his patriotic duties”. The reminiscences do not, however, reveal much of how this was undertaken, other than by draconian discipline. The ‘enlightenment lectures’ given by the military priests are hardly mentioned. A few men bring up that officers delivered patriotic speeches on festive occasions such as when the soldiers gave their oath of allegiance or were disbanded. Traces of the political re-education project mainly become visible in recollections of the ban on socialist newspapers and other leftist publications in the garrison areas, permanently reminding conscripts from a “red” background that their citizenship was seen as questionable.

Certain cafés and restaurants in the garrison towns that were associated with the workers’ movement were also out of bounds for conscripts on evening leaves. Some informants write about how conscripts were anxious to conceal their family association with the red rebellion or the workers’ movement from the officers in fear of harassment. Many informants mention that certain conscripts’ advancement to NCO or officer training was blocked because of their or their families’ association with the political left – a view confirmed by recent historical research. Some of the officers might very well have had rational and articulate ideas about the functionality of harsh and humiliating methods. However, as described above, many Finnish military educationalists in the 1920’s already viewed this traditional military pedagogy as counter-productive to the needs of a national Finnish army whose effectiveness in combat had to be based on patriotic motivation and not on numbers or ‘machine-like obedience’. Neither did the men who personally experienced interwar military training later choose to present the bullying as somehow productive of anything positive, be it discipline, group cohesion, or a new military identity.

Physical Training in Military Service

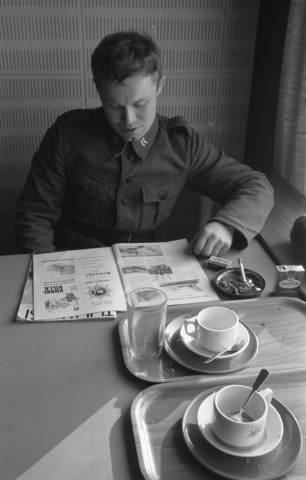

Yrjö Norta (b Turku 1904, d Helsinki 1988, Finnish filmmaker)recording soldiers doing Drill for a promotional film (1927)

Conscription dislocated young men from family and working life into garrisons and training fields, packed them into dormitories of 20 to 50 men, robbed them of personal privacy, infringed on their integrity, and demanded they performed extreme physical tasks. It toughened men through gymnastics, drill, sports and field exercises. It trained men into particular postures and ways of moving as well as an attitude marked by a recklessness towards vulnerability. Yet physical vulnerability did put limits to what the men could be put through. And conscripts faked or inflicted illness and injuries upon themselves to evade training.

Physical Inspection and Assessment

The first concrete contact with conscription and military service for a young man was actually the call-up inspection. The colloquial term often used in Finnish for the call-up, syyni, refers to viewing or gazing – to the conscript being seen and inspected by the call-up board. As most men remembered the call-up, the youngsters had to undress in the presence of the others called up and step up stark naked in front of the examination board. Juha Mälkki characterises this practice as part of the “inspection mentality” of the era. It was evidently an embarrassing or at least peculiar experience for many conscripts, since it often needed to be treated with humour in narration, giving rise to a large number of anecdotes. One of these stories demonstrates how joking was used at the call-up itself as a means of defusing the tense situation of scores of young naked men being inspected by older men behind a table. Albert Lahti remembered that a young man at his callup tried to cover his genitals with his hands as he stepped up on the scales to be weighed. A local district court judge corrected him tongue-in-cheek: “Come, come, young man, don’t cover anything and don’t lessen the load. Step down and take your hands off your balls and then step up on the scales once more so we can see your real weight. – You don’t get away as a crown wreck that shamelessly!” The boy did as he was told and steps back upon the scales with his hands at the sides and is greeted by the judge: “All right, what did I tell you, four kilogrammes more weight straight away as you don’t support those balls”. Laughter rolled around the room where a ”court room atmosphere” had reigned the moment before. The joke was on the boy on the scales – according to the end of the story he afterwards asked his comrades in round-eyed wonder whether his balls could really be that heavy. For that, he got the nickname ”Lead Balls”.

At the call-up, conscripts were sorted into those fit and those unfit for military service. As such, there was nothing very particular about the criteria applied. In the military, just as in the civil sphere, it was considered superior for a man to be strong, not weak, tall rather than short, have good eyesight and hearing, well-shaped limbs and no serious or chronic diseases. Yet hardly anywhere else at this time was such a systematic examination and comparison of conscripts’s made, accompanied by a categorical sorting strongly associated with masculine pride or shame over one’s own body. The physical examination at the call-up often stands out in the memories of military service and appears to have left behind strong images in memory. Even if few men probably were looking forward to their military service, being categorised as fit for service was still a matter of honour, whereas being exempted on the grounds of being physically unfit carried a strong stigma. The colloquial term for those discarded, ruununraakki, literally translates as “crown wreck”, somebody whose body was such a wreck that it was not good enough for the crown, for serving the country as a soldier. According to many informants, the ‘crown wrecks’ were shown contempt in the interwar years, also by young women who would not accept their courtships. Historian Kenneth Lundin has noted that in 1930’s feature films set in the conscript army, the ‘crown wrecks’ were always depicted as lazy, fat malingerers. Urpo Sallanko (b. 1908) recounted in his memories that he was very nervous at the call-up because he was of small stature. Both his older brothers had been categorised as ’crown wrecks’ and discarded. Hearing about his brothers, a neighbour woman had told the other women in his home village that ”she would be ashamed to give birth to kids who are not good enough to be men of war. This naturally reached my mothers ears,” Urpo wrote, “and made her weep”. Lauri Mattila’s friend Janne was sent home “to eat more porridge” because of his weak constitution and “was so ashamed of his fate that he never told anyone about what happened to him at the call-up”.

This notion of ’crown wrecks’ seems to have been a tradition from the days of the ’old’ Finnish conscript army in the 1880’s and 1890’s. At that time, roughly one tenth of each age cohort was called up for active service and about a third for a brief reserve training. The military authorities could thus be very selective at the call-up examinations, only choosing the physically “best” developed for the drawing of lots that determined who had to do three years of active service and who was put in the reserve. According to Heikki Kolehmainen (b. 1897), this tradition was alive and well in the countryside when he entered service in 1919. “You would often hear old men tell about the drawing of lots, about their service in the reserve or the active forces, and like a red thread through those conversations ran a positive, even boastful attitude of having been classed fit for conscription in those days. We [youngsters] accordingly thought of those who had served for three years as real he-men, of those who had served in the reserve as men, and of the crown wrecks as useless cripples.” Nevertheless, the ’crown wrecks’ were a group of considerable size. In the days of the “old” conscript army, at the end of the nineteenth century, around half of each age cohort was exempted.

Being in higher education or being a sole provider were valid grounds for exemption, but a weak physique was the most usual reason. In the 1920’s, about one third of each male age class never entered service on these grounds, and towards the end of the 1930’s roughly one man in six was still discarded. Claims that politically “untrustworthy” men would have been rejected under the guise of medical reasons have, however, been convincingly refuted by historical research. Historian Juha Mälkki claims that the number of men who received military training precisely met the manpower needs of the planned wartime army organisation and that the number discarded would thus have been governed by operative considerations in interwar Finland. Nevertheless, the high rejection rates caused public concern over the state of public health. Somewhat surprisingly, these numbers were not kept secret, but discussed openly in the press. Being a “crown wreck” was thus not an existence on the margin of society, but rather usual. Although being fit for service was probably associated with toughness by most contemporaries, the stigmatisation of being discarded might be exaggerated in both the collected reminiscences and interwar popular culture.

Toughening and Hardening the Conscripts

The army stories emphasise the toughness and hardships of military service, but also depict a military culture where the individual soldier was trained to physically merge with his unit and become indifferent to nakedness, pains or vulnerabilities. He became part of a collective. The initial physical inspection at the call-up can be interpreted as a stripping of the youngsters’ old, civilian identities, as a symbolic initiation that was repeated and completed months later, when the recruit arrived at his garrison and had to hand in his civilian clothes and don the uniform clothing of the army. In the light of the reminiscences, it seems that stripping naked was rather an introduction to a military culture where there should be nothing private about one’s body. Once the recruits entered service they had virtually no privacy. They spent their days and nights in a group of other men; sleeping, washing, and easing nature in full visibility of a score of other youngsters. The scarcity of toilets, causing long queues, and going to the latrine at camp in close formation with one’s whole unit stand out strongly in some men’s memories. Even more colourful are descriptions of the so-called “willie inspection” as the men stood in naked in line to be very intrusively inspected for symptoms of gonorrhea and other venereal diseases. Janne Kuusinen still remembered fifty years later that some men were ashamed the first time they had to undergo this and would not take off all clothes, that some men caught a cold as they were made to stand naked for over an hour, and that one man was diagnosed with tight foreskin and sent to surgery the next day. This ruthlessness concerning the conscripts’ privacy can be understood as either sheer brutality or as a part of training intended to do away with any feeling of physical individuality. A soldier should neither be shy nor self-conscious.

Army stories display the pride men felt over having been found fit for military service at the call-up. However, in many stories conscripts were greeted as too soft and immature upon reporting for duty, as mere “raw material” or “a shapeless mass of meat” that completely lacked the strength, toughness, skills and comportment required in a soldier. At every turn, the recruits were reminded that they were not yet physically fit for war, but needed ruthless training and hardening. Their status as complete greenhorns was in many units manifested through physical manifestations. Their hair was cut or even completely shaved off, in some units this was administered by the older soldiers as part of a “hazing” ritual. They were allotted the shabbiest and most worn-out uniforms and equipment. “Dreams of soldier life in handsome uniforms were roughly scrapped on the very first day”, commented Eero Tuominen, who ten months later became a storekeeper sergeant himself, and remembered as the greatest benefit of this new position that for the first time he could get a uniform tidy enough to visit a theatre. Valtteri Aaltonen realised that the Finnish soldiers on home leave in neat uniforms with the insignia that he had seen in his home district were “an idealised image”, as he entered the garrison, saw the soldiers in their everyday clothes and got his own kit. Jorma Kiiski claims one recruit in his unit was given a shirt that had 52 patchs. The stories about torn and unsightly uniforms mainly date from the early to mid–1920’s, but informants serving in later years also remember that the storekeeper sergeants were demonstratively rude to the new recruits and seemed to make a point of handing out boots and uniforms in impossible sizes to each of them.”

In official debates on military education, physical training of Conscripts centred on gymnastics, sports and athletics. The official Sports Regulations for the armed forces, approved by the Minister of Defence in 1924, underlined how modern athletics derived their origins from ancient combat exercises.

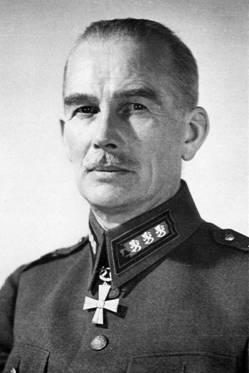

Vilho Petter Nenonen (March 6, 1883, Kuopio – February 17, 1960) received his military education in the Hamina Cadet School 1896-1901, in the Mihailov Artillery School in St Petersburg 1901-1903, and in St Petersburg Artillery Academy 1906-1909. He served in the Russian army during World War I. When the Finnish Civil War began he moved to Finland and was given the job of creating the artillery of General Mannerheim’s White Army. After the war he also served as the Minister of Defence between 1923 and 1924. During the Continuation War he was a part of Mannerheim’s inner circle. He was promoted to the rank of General of the Artillery in 1941. Nenonen developed the Finnish Army’s artillery and tactics that proved decisive in the defensive victory in the Battle of Tali-Ihantala. The trajectory calculation formulas he developed are still in use today by all modern artillery. He received the Mannerheim Cross in 1945.

Sports, it was stated, especially team games, developed the soldiers’ mental as well as physical fitness for modern warfare. The regulations gave detailed instructions for baseball, football, skiing, swimming, and a number of branches of athletics. However, according to historian Erkki Vasara, the regular army never received sufficient funding for sports grounds and equipment during the interwar years. In this area, the Suojeluskuntas (Civil Guards) were much more advanced than the regular army. Sports and athletics in the army focussed on competitions between different units and therefore mainly engaged the most skilled sportsmen among the conscripts.

For most conscripts, physical education meant morning gymnastics, close-order drill, marching and field exercises. The physicality of military training was remembered by some in terms of stiffness, strain and pain. Military training especially in the 1920’s emphasised a “military” rigidity in comportment and body language. Instructors gave meticulous guidelines for standing at attention: protrude your breast, pull in your stomach, set your feet at an angle of 60 degrees to each other, keep your elbows slightly pushed forward, and keep your middle finger at the seam of your trousers, etc. Paavo Vuorinen (b. 1908) remembered one sergeant major who made every formation in line into an agonising experience: “I guarantee that a [very small] ten penny coin would have stayed securely in place between one’s buttocks without falling down, as we stood there at attention, as if each one of us had swallowed an iron bar, and still [the sergeant major] had the gall to squeak with a voice like sour beer: ”No bearing whatsoever in this drove, not even crushed bones, just gruel, gruel … Incessant, impertinent barking all the time, utter insolence really. Finnish military education in the interwar period followed the general European military tradition, originating in the new emphasis on military drill in the seventeenth century, where recruits had to learn new “soldierly” ways of moving, even how to stand still. The soldier was robbed of control over his own posture, even the direction of his eyes. Jorma Kiiski (b. 1903) understood this training in a carriage as a dimension of the pompous theatricality of the ”Prussian discipline”. “There was a lot of unnecessary self-importance, muscle tension to the level of painfulness, attention, closing the ranks, turnings, salute, yes sir, certainly sir, no matter how obscure the orders.”

Stories about the harshness and brutality of military training entail strong images of how the Conscripts were put under extreme physical strain. An important element in the stories is the ruthlessness shown by superiors as they pushed the conscripts beyond their physical limits. Kustaa Liikkanen relates how his unit was on a heavy ski march in full marching kit. Two conscripts arrived exhausted at the resting-place a good while later than the rest. The sergeant-major started bellowing about where they had been, making them repeatedly hit the ground, barking, “I’ll damned well teach you about lagging behind the troops. Up! Down! Don’t you think I know what a man can take! Up! Down!” To ”harden” the soldiers and simulate wartime conditions, or sometimes only as a form of punishment, Officers made their men march until some fainted. Eino Sallila took part in a field manoeuvre lasting several days. On the march back to the garrison, he claims, many conscripts were so exhausted that they fainted and fell down along the road. One fainting soldier in Sallila’s group rolled down into a ditch filled with water, but when Sallila ran to pick him up, an officer roared at him to let the man lie. Back at camp, a higher-ranking officer praised the men for their efforts, adding that in order to understand the exertions they had been put through, “you have to be aware of the purpose of the exercise – we are exercising for war.” Sallila sourly commented in his memories that had the enemy attacked on the next day, the whole regiment would have been completely disabled.

The army stories portray some officers as unflinching in their view that smarting and bleeding sores were something a soldier must learn to doggedly endure. Kalle Leppälä had constantly bad chafes on his feet during the recruit period, due to badly fitting boots. “Sometimes I bled so much in my boots that I had to let the blood drop out along the bootlegs in the evening. I never complained about the sores, but took the pain clenching my teeth. It was pointless complaining about trifles, that I gradually learned during my time in the army; I did not want to become known as a shirker.” Viljo Vuori (b. 1907) had so bad sores during a march that the medical officer told him to put his pack in the baggage, but when his company commander found out about this, he was ordered to fetch the pack and continue marching. The next day, Vuori was unable to walk and the foot was in a bad condition for a long time. Both the medical officer and the company commander probably foresaw this physical effect of marching on with the heavy pack, but where the physician found it necessary to stop at this physical limit, the other commander thought the conscript must learn to press himself through the pain, even if it would disable him for weeks. Pentti Haanpää portrayed the physical “hardening” of conscripts in a short story about a recruit who tells his second lieutenant he is ill and cannot take part in a marching exercise, but is dismissed; “A soldier must take no notice if he is feeling a bit sick. You must hold on until you fall. Preferably stay standing until you drop dead. Get back in line.” The sick conscript marches ready to faint and vomits at the resting place. An older soldier hushes him away from the spew, making him believe he will be in even greater trouble if the second-lieutenant finds out, only to then pretend to the passing officer that he himself has been sick. The “old” soldier gets a seat in a horse carriage and the sick recruit learns his lesson. In the army, a man must learn to endure hardships, but above all acquire the audacity and skilfulness to shirk duty and minimise the strain.

The military discipline regulated many areas of the conscripts’ life yet at the same time military culture had a quality of brisk outdoor life that in some stories is portrayed as invigorating or even liberating. In Haanpää’s stories, the physical training appears to be strenuous work that produces no results, at least none that the soldiers comprehend. The Finnish conscript depicted by Haanpää enjoys disbandment not least as a physical release from the straitjacket of the strictly disciplined military comportment, relaxing his body and putting his hands deep down into his pockets. Mika Waltari and his comrades, on the contrary, experience some elements of military life in terms of freedom from the physical constraints of school discipline and urban middle-class family life. Waltari’s initial impressions of life at summer camp are marked by physical sensuousness and the cultured town-dwellers romanticisation of rough and masculine outdoor life. “We enjoy that our hands are always dirty. We can mess and eat our food out of the mess-kit just as we like. We do not have to care at all about our clothes. We can flop down on the ground anywhere we like and roll and lounge.”

Pride in Endurance

Pressing one’s body to extreme physical performances could also be a positive experience and a matter of honour and pride. Many informants highlight the experience of their heaviest marches in full pack, by foot or on ski, lasting several days. Kustaa Liikkanen mentions with marked pride how he pulled through a seven-day skiing march with 18 kilograms of pack plus his rifle and 100 cartridges of live ammunition. Lauri Mattila remembered an extremely heavy 32-hour march, including a combat exercise, in sweltering summer heat with full pack. The boots and pack chaffed the soldiers’ skin on the feet, thighs and shoulders. Dozens of soldiers fainted along the way. They were driven by ambulance a few kilometres forward and then had to resume marching. Nonetheless, Mattila recalled the march as a kind of trial that none of the men wanted to fail. “It was a march where everything you can get out of a man by marching him was truly taken out. It was a matter of honour for every man to remain on his feet and march for as long as the others could march and making the utmost effort ….if they fainted and fell they would be trampled underfoot by those behind”. Mika Waltari actually describes the painful experience of a heavy marching exercise in more detail than Haanpää; the scorching summer sun, the sweat, the thirst, the weight of the pack, straps and boots chafing and cutting into the skin, hands going numb and eyes smarting from sweat and dust, the mounting pain in every limb and the increasing exhaustion. “In my mind there is only blackness, despairing submission, silent curses rolling over and over.” Yet as soon as Waltari and his comrades are back at camp they start bickering and cracking jokes about how they could have walked much further now they had been warmed up, and they proudly compare their sores and blisters. They happily tell each other that the major has praised their detachment. Once they have been for a swim and bought doughnuts from the canteen, Waltari describes their state of mind and body as virtually blissful: “We are proud and satisfied beyond imagination. It only does you good, comrades! Who the heck would like to be a civilian now? Nowhere else can you reach such a perfect physical feeling of happiness.”

In Waltari’s eyes, the army fosters ”healthy bodies accustomed to the heaviest strains, more and more hardened men than in civilian circumstances.” Waltari himself appears to have been eager to demonstrate his fitness, to prove that in spite of being an intellectual, artist and town-dweller he could cope with the military and even enjoy his training. He really lives the part and seems to regard his toughness as proven and recognised by the physical hardships he has endured. Just as in Lauri Mattila’s narrative, it is a matter of honour to Waltari and his comrades to “take it like a man” and cope with whatever the others manage. Even if many army stories signalled disapproval of the physical treatment of conscripts, the narrative tradition conveyed a cultural knowledge about what a healthy conscript had to take and what he should endure. Enduring physical strain and pain without complaint and without breaking down was not so much idealised as portrayed as a grim necessity.

Conscript Resistance

Physical Training was a central arena for the power struggle that often raged between the soldiers and their superiors, where Officers and NCOs tried to enforce subordination through punishments directed at the connscripts in the form of strain, exhaustion and pain. Conscripts resisted this treatment through injuries and illness, real or faked. During the first years after the Civil War, as many conscripts were undernourished, the exercises and punishments could be dangerously exhausting. “The exercises were tough, get up and hit the ground until the boys were completely exhausted and the weakest fell ill and at times the hospital was full of patients. Throughout the 1920’s, however, the press reported on how men returning from military service gave an appalling picture of poor sanitary conditions and deficient medical services. One non-socialist daily local newspaper wrote in 1925, “Ask the gentleman, whose son has performed military service, ask the peasant or the worker, and the answer shall very often be that the youngsters have been badly neglected, overstrained, been treated according to all too Prussian methods. […] There’s talk of lifethreatening illnesses contracted in the military service, talk of deaths, of overstrain due to unacceptable punishment methods, of venereal disease due to shabby clothing handed out to the young soldiers, of tuberculosis contracted through transmission from sick soldiers. […] A father whose healthy son has returned ruined by illness will become an irremediable anti-militarist and strongly influence his environment, and a father whose son has been conscripted in spite of sickness and returned with ruined health can be counted to the same category.”