Before we return to the Foreign Press for a final summation, it’s perhaps also worth taking a look at the Finnish Press and the Winter War – more specifically, how the Finnish newspapers reacted to, and reported on, the Winter War. This is more relevant that it at first seems, as many foreign correspondents picked up translations of Finnish newspaper articles for their own use. Also, both the Finnish newspapers and the foreign correspondents relied to an extent on the daily media releases from the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus (VTK, or State Information Centre). Add to this the strong sympathy and support that almost all of the foreign correspondents felt for Finland and foreign reporting took on a more and more “Finnish” viewpoint as the War continued. This, a look at the Finnish Press is certainly both relevant and justified.

When examining coverage of the Winter War in the Finnish Press, we are dealing largely with the nation’s defence. Questions dealing with the enemy and hostilities were naturally a dominant daily topic in Finnish newspaper editorials and articles and the subsequent reputation of the Winter War is dominated by an image of the Finns’ complete unanimity. Examining the sources strengthens this view because the language used during the war appears remarkably similar in all newspapers, and every paper pretty much described the enemy using the same negative arguments and views, regardless of previous political affiliation. In general, one can say that Finns in general already had a preconceived mental image of the Soviet Union created over different periods and the unprovoked Soviet attack on Finland dovetailed into this.

This view had its roots in the repeated invasions of Finland and its seizure from Sweden in the eighteenth century, followed by the increasing nationalism and a desire for independence from “the loathsome embrace” of Russia in the nineteenth century. The achievement of independence in 1917 and the subsequent Civil War between the Whites and the Reds in 1918 had resulted in a stirring up of hatred against Russians and an increasing fear of communism, especially among influential right wing movements such as the Akateeminen Karjala Seura (AKS or “Academic Karelia Society) and the Lapua Movement (Lapuanliike). While some political parties perhaps could be considered more nationalist than others, the negative image of the Soviet Union permeated the entire Finnish middle class and indeed, was also widely held among leftists, excluding only the extreme left, largely as a result of events in the Soviet Union in the 1930s and the purges of the late 1930’s, news of which was well known in Finland, where refugees from across the border regularly arrived. Thus, the Finns image of the USSR had centuries-long roots due to a common history that included repeated conflicts, occupation and oppression.

Since independence, the Finnish military had viewed the USSR as the only potential threat to Finland. Through the 1930s Finnish military preparations had been directed towards meeting this threat. Care was taken however, even by the rightist politicians, not to unduly inflame relations with the neighbouring giant. Indeed, at the same time as Finland was increasing defence spending through the 1930’s, every effort was being made to increase reciprocal trade with the USSR and tie both countries into a mutually beneficial relationship. However, the Purges of the late 1930’s and the execution and deportation of large numbers of Karelians and Ingrians across the border were well-known in Finland and despite not being made much of in the Finnish Press, the activities of the NKVD reinforced the negative views of many Finns with regard to the Russians. This negative image of the Russians became ever more pronounced in late 1939 with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, the “stab in the back” of Poland, the “agreements” with the Baltic States and then the pressure on Finland to adjust the borders and grant the USSR bases in strategic Finnish locations. In all of these acts, the USSR ensured that it was the very archetype of the same enemy that had repeatedly attacked and oppressed Finland in the past.

On the outbreak of the Winter War, Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus (VTK, the State Information Centre) had very little work to do to create a negative image of the enemy that would unite all Finns. The actions of the USSR achieved this quite successfully, creating an enemy “tailor-made” for the media, both Finnish and foreign, to demonise with ease. Influencing public opinion within Finland to adopt and receive views the government wished it to adopt and receive in this regard was not a great challenge. Nor was it a challenge to suitably influence the foreign press. This also was a relatively easy task that the Finns generally left to the USSR to achieve for them, something which the USSR did quite effectively, turning even former sympathizers such as John Langdon-Davies into outright opponents. The biggest challenge turned out to be detailed censorship of military information and the development of information-sharing guidelines associated with military topics and the actual fighting. Thus, censorship and the provision of information to the press was not so much a political question as a military one, due to the unanimity shared between the press, both local and foreign, and the people.

Non-Socialist Finnish Newspapers

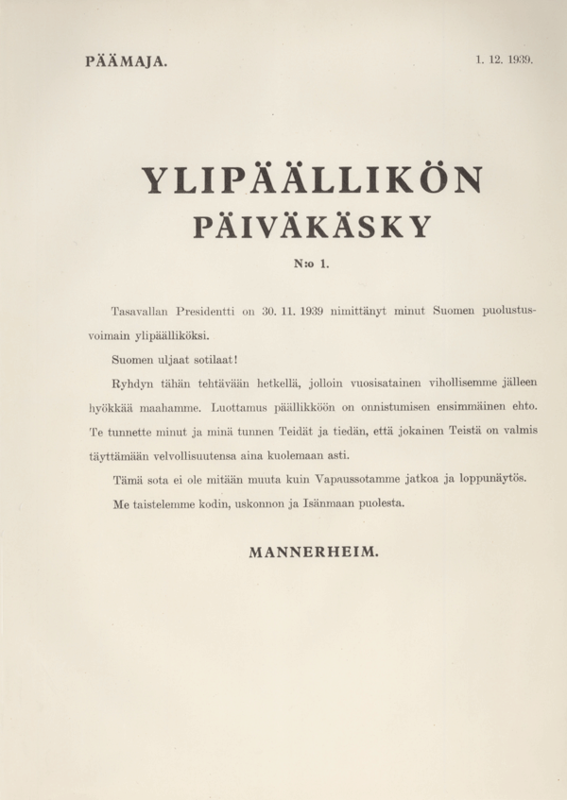

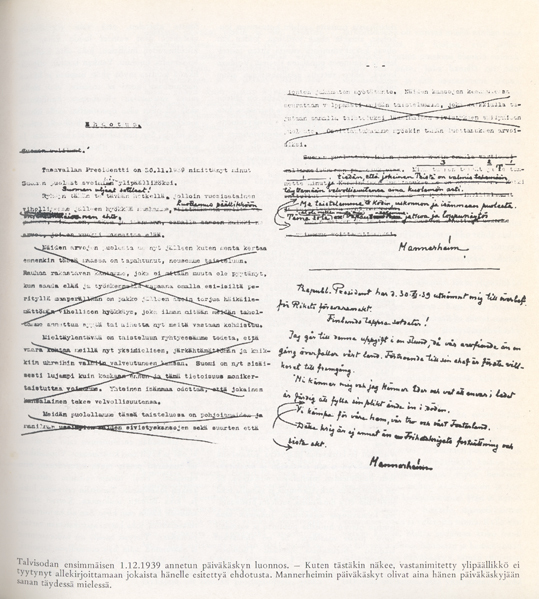

When the portrayal of the enemy in the Finnish news media is examined more closely however, differences emerge in the seemingly unified descriptions of the enemy. Different ideologies and ideals existing in the country are reflected in the image of the enemy created by newspapers – because of course the papers naturally wanted to appeal to their own particular groups of readers. For readers with right-wing inclinations, which included many members of the Agrarian party, the emphasis was on a patriotic war of national defence. This was the view that made its appearance in the first Order of the Day of the Military Commander, the Marshal of Finland, C. G. E. Mannerheim.

Commander-in-Chief’s Order of the Day No. 1.

On 30 Nov 1939, the President of the Republic has appointed me Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces.

Valiant soldiers of Finland!

I accept this task at a moment when our centuries-old enemy is once again attacking our country. Confidence in an army commander is the primary condition for success in war. You know me, and I know you and I know that each and every one of you is prepared to fulfil his duty even unto death. This war is merely a continuation and final act of our War of Independence.

We fight for our homes, our religion and for our Fatherland.

MANNERHEIM

This view, succinctly expressed in Mannerheim’s first Order of the Day, presented the war as a battle of national defence in which the Soviet Union threatened home, religion and the fatherland. It also included a theme which had been emphasized throughout the 1920s and 1930s in Government, Suojeluskuntas and Army publications and by nationalist and conservative groups, namely that the Civil War of 1918 was a War of Independence (or War of Liberation) from the Russians. In the non-Socialist Finnish newspapers, this view and the history behind it was utilized from the very start of the war.

These non-Socialist Finnish papers described and made use of the historic connections between Russia and Finland. Old conflicts were used for comparison, mainly the Great Wrath. With the help of these, it was possible to describe that the Soviet Union was Russia’s successor and also very demonstratably the archenemy. It was “that old tormentor” which throughout history had attacked Finland and forced every generation to defend the country. The image of the USSR that was presented by the conservative factions in Finland, most explicitly by the right AKS and the Lapua Movement was utilised. Understandably this image was the strongest in papers of the extreme right and of the Agrarian Union and is seen in these papers from the first days of the war. Because war is generally a unifying force, it is not surprising that this enemy image based on history soon found its way into the newspapers of the political centre and occasionally into newspapers of the Left.

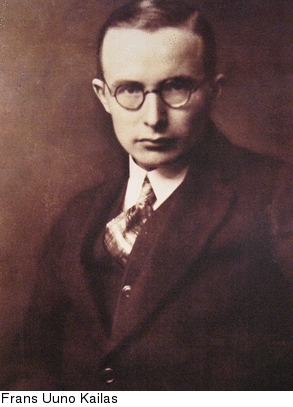

This “image of the enemy” also included appealing to the cultural difference between the Finns and the Russians and the Russians’ difference from the western peoples. Uuno Kailas’ famous poem “Rajalla” (On the Border) was well-known and was often referred to over the course of the Winter War, even finding its way into an English translation and being printed in foreign news articles about the Winter War:

Photo, Left: Uuno Kailas, born Frans Uno Salonen (29 March 1901 – 22 March 1933) was a Finnish poet, author, and translator. After his mother’s death when he was young, he received a strict religious upbringing from his grandmother. He studied in Heinola and occasionally in the University of Helsinki. In 1919, he took part in the Aunus expedition, where his close friend Bruno Schildt, whom he had persuaded to take part, was killed. Kailas’ critical reviews and translations were published in Helsingin Sanomat and the literary magazine Nuori Voima. His first collection of poetry was “Tuuli ja Tähkä” in 1922. Kailas served in the army from 1923 until 1925. The ideology of the right-wing movements in Finland is strongly reflected in Kailas’s poem “Rajalla” (On the Border). Like Kipling, Kailas saw an unresolved antagonism between East and West, seeing Finland as the guardian of Western culture on the Soviet border. In 1929, he was hospitalized due to schizophrenia, and he was also diagnosed with tuberculosis. He died in Nice, France in 1933, and was buried in Helsinki.

Rajalla (On the Border)

Raja railona aukeaa (Like a chasm runs the border)

Edessä Aasia, Itä. (In front, Asia, the East)

Takana Länttä ja Eurooppaa; (Behind, Europe, the West)

varjelen, vartija, sitä. (Like a sentry, I stand guard)

Takana kaunis isänmaa (Behind, the beautiful fatherland)

Kaupungein ja kylin. (with its cities and villages)

Sinua poikas puolustaa (Your sons defend you)

Maani, aarteista ylin. (My country, the greatest treasure)

Öinen, ulvova tuuli tuo (Nocturnal howling winds bring)

Rajan takaa lunta. (Snow from across the border)

— Isäni, äitini, Herra, suo (Lord, let my mother and father)

Nukkua tyyntä unta! (Sleep, calmly dreaming!)

Anna jyviä hinkaloon, (Fill the bins with grain)

Anna karjojen siitä! (Let the herds breed)

Kätes peltoja siunatkoon! (Let thy hand bless the fields)

– Täällä suojelen niitä. (I am here, protecting them)

Synkeä, kylmä on talviyö, (The winter night is dark and cold)

Hyisenä henkii itä. (There is an Icy breath from the East)

Siell’ ovat orjuus ja pakkotyö; (Over there is slavery and forced labour)

tähdet katsovat sitä. (the stars look down and see)

Kaukaa aroilta kohoaa (Far away on the Steppe rises)

Iivana Julman haamu. (The ghost of Ivan the Terrible)

Turman henki, se ennustaa: (A spirit of doom is at work, predicting that

verta on näkevä aamu. (the morning shall see blood)

Mut isät harmaat haudoistaan (The gray fathers rise from their graves)

aaveratsuilla ajaa: (Phantom steeds they ride)

karhunkeihäitä kourissaan (Bear spears in their hands)

syöksyvät kohti raja (Rushing to the border)

—Henget taattojen, autuaat, (Blessed spirits of the fathers)

kuulkaa poikanne sana — (Listen to your sons words)

jos sen pettäisin, saapukaat (if I should not keep my word, then come)

koston armeijana —: (as an army of vengeance)

Ei ole polkeva häpäisten (Their tread will not desecrate)

sankarileponne majaa (the resting place of your heroes)

rauta-antura vihollisen, – (From the iron-soled foot of the enemy)

suojelen maani rajaa! (I will protect your borders)

Ei ota vieraat milloinkaan (Strangers will never take)

kallista perintöänne. (your precious heritage)

tulkoot hurttina aroiltaan! (let them come like hounds from the steppes)

Mahtuvat multiin tänne. (they will find a place here under the soil)

Kontion rinnoin voimakkain (With a bears powerful chest)

ryntään peitsiä vasten (I charge against the lances)

naisen rukkia puolustain (defending your women’s spinning wheels)

ynnä kehtoa lasten. (and your children’s cradles)

Raja railona aukeaa (Like a chasm runs the border)

Edessä Aasia, Itä. (In front, Asia, the East)

Takana Länttä ja Eurooppaa; (Behind, Europe, the West)

varjelen, vartija, sitä. (Like a sentry, I stand guard)

Finland certainly had strong reasons for identifying with the west following the national awakening in the mid-19th century, and it had been actively emphasizing the need for national unity – which included stirring up an antipathy towards the Soviet Union in the early years of the independence period. This topic was also dealt with by propaganda directed outside Finland during the war. This propaganda was used to influence public (and government) opinion in other countries by emphasising that the Soviet Union’s attack against Finland was not only aimed at conquering Finland but towards the entire world and a worldwide revolution. Therefore, it was in the best interest of those countries to help Finland. This propaganda, thus, had a clear practical goal and, because we are expressly dealing with the best interests of Finland fighting a defensive war, it is understandable that the domestic newspapers also wrote about the need for help from foreign countries.

The ideological differences between the different Finnish newspapers did not differ on this – almost all Finnish newspapers soon came to reflect this viewpoint, regardless of their previous ideological perspective, There were, however, differences in the volumes of articles with this theme. This may also be explain by the desire to influence foreign opinion because liberal Helsingin Sanomat, the largest newspaper of the country and the newspaper whose content was most often translated and used abroad in the British Commonwealth countries and in the USA, included the most articles on this topic. This paper was owned by Elias Erkko – a former Foreign Minister – and opinions expressed in this paper were definitely followed abroad and through the foreign diplomatic missions in Finland.

Finnish Labour newspapers

The Labour Movement newspapers were expressly newspapers of the Social Democratic Party, which as one of the parties making up the government, condemned the Soviet Union’s attack as unequivocally as did other newspapers (the Finnish Communist Party was banned). When we examine the content of the SDP’s newspaper dealing with the enemy, the SDP’s worldview is brought up as well as the practical need to encourage the working class to defend the country. The need for national unity in a war of survival for Finland was emphasized as being essential to military success. Thus the Soviet Union was examined from a somewhat different point of view than that of the non-labour movement newspapers.

It was of course not particularly useful to appeal to the working class left with the memories of their defeat in the Civil War in 1918. What did appeal was the condemnation of the imperialism of the Soviet Union and Stalin, separating thus from the ideals of the Finnish labour movement, which were assumed to be shared by readers of the SDP-supporting newspapers. For this reason it was emphasised in the labour newspapers that the Soviet Union had violated the most cherished and central principles of the labour movement by attacking its small neighbour. This meant that the ideals of socialism and working class ideology that had emerged during the revolution were no longer honoured in the Soviet Union.

This indicates that the motives behind these articles were clearly different from those expressed by the non-socialists. Later in the War, the labour newspapers also attempted to influence their readers’ opinion by emphasising the social development that had taken place in Finland since independence. Always in the background was a need to emphasise that Finland was worth defending from the point of view of the labour class – and this idea was apparently influential. The basis for the success of this line of propaganda was created by the events that took place in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, particularly the purges of Finns in Karelia – and as these events were relatively well known in all groups in Finland, it was possible to use mentions of these to remind readers of what the working class was going to lose if Finland was defeated. There was no need for the non-labour newspapers to emphasise the more democratic and humane nature of the Finnish society in comparison to that of the Soviet Union. It was clear without stating this explicitly. Therefore, it was typically only the labour newspapers that made an effort to demonstrate the issue by presenting arguments.

The Words and Deeds of the Soviet Union as reflected in Finnish Media

From the beginning of the war, news and commentary were intertwined in newspapers, and newspaper reporters freely expressed their views of the enemy’s actions and character in the news pages and headlines. All the Finnish newspapers used content from the Soviet Union’s own propaganda and actions which generously reinforced the preexisting image of the enemy in Finnish eyes. When the war began, Radio Moscow proclaimed on 1 December 1939 that the people of Finland had raised a rebellion against the white government and said that a new Finnish Government had been established at Terijoki. This government, for its part, proclaimed that it had requested help from the Red Army to suppress Finland’s White Guard government and had signed a mutual assistance agreement with the Soviet Union on December 2nd. With this assistance, it was certain that every Finn now knew that the whole of national independence was at stake, not only some strategic territories on the eastern border.

The Finnish government apparently felt some degree of concern about the influence of the Terijoki government on opinions at the beginning of the war, influenced by a fear that the Soviet Union’s propaganda maneuver would appeal to at least some members of the extreme left. Such concerns proved to be without any basis as the Terijoki “government” was ferociously condemned by the labour newspapers in many editorials and commentaries. The non-socialist press also judged the Terijoki government to be a sub-standard move by the Soviet Union but of course, they did not need to feel similar worry about their readers’ views.

The entire Finnish press considered the Terijoki government an example of “typical” Soviet duplicity. When it promised the Finns an eight-hour workday, which Finland had already had for more than two decades, this poor knowledge of conditions in Finland was utilised in the Finnish press. Many more minor mistakes of the Soviet Union were also exploited to create a poor image of the Soviet enemy. Descriptive examples of these are provided by radio programs directed by the Soviet Union to Finland in which it was reported that Finns ran toward the Red Army soldiers at the borders to hug and kiss them. The Soviet Union’s Finnish-language programs commonly reported that soldiers of the Red Army had received a “hot” reception at the borders, apparently meaning friendly and warm. The non-socialist Finnish newspapers milked everything possible out of the double meaning of this Finnish word. For once “Ryssä” speaks the truth – they certainly received a “hot” reception – that is, they had came under heavy fire – and they would in the future also receive a “hot reception”, they wrote with amusement.

The aerial bombing carried out by the Soviet Union had a stronger effect on the image of the Russians as enemy than even the Terijoki government. There had been attacks against civilians in the Spanish Civil War, but in the Second World War, which started in September 1939, Germany, England and France had not carried bombing attacks against each other’s civilians (although the Finnish Press had reported on the German bombing of Warsaw and of Rotterdam). For this reason, the Soviet Air Force bombings of Helsinki and other cities awoke the old image of the Russian as a traditional enemy – and an enemy for whom the killing of Finnish civilians in war was characteristically and traditionally a Russian activity. The Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov said at the beginning of the war (and continued to repeat through January) that the Soviet Union had not bombed civilian targets in Finland. The Finnish newspapers reported this with anger and reported that Molotov had also said that rather than bombs, the Russian planes dropped bread to starving Finnish workers. When Soviet bombers circled in the sky they were, after that, referred to as “Molotov’s breadbaskets”- and it was reported to astonished readers that entire buildings had collapsed due to the weight of the Soviet bread. Similarly, the howling of alarm sirens came to be called “the voice of Molotoff”. It was in this way possible to utilise a person, Molotov, as an image at which to direct people’s feelings of hatred. Whether or not claims presented to the public by Soviet propaganda were created for their own domestic propaganda was naturally not deliberated during the war. On the other hand, when they were presented in radio broadcasting directed at Finland there might have been a desire to also appeal to the Finnish workers in some way.

The image of the Russian enemy in which evil deeds are seen as being due to the national character of the Russians first appeared in right wing and agrarian party newspapers. In this viewpoint, the negative image of the Soviet Union had strong roots in the atmosphere of the Independence and Civil War period, which was strongly coloured by a hatred of the Russians and the fear of communism. At Christmas 1939, when the Soviet air bombings recurred, the non-socialist newspapers further developed the Great Wrath theme in the emotional atmosphere of the war. They started to write about the “Holy Wrath,” in which Finland defended all western and Christian values against the Asian communist barbarians – Finland was fighting for the sake of all Europe. This was a view that was rapidly reflected in almost all of the conservative newspapers of both the western democracies and of countries such as Italy and Spain. In the conservative newspapers of Britain and France, much was also made of the fact that the Soviet Union and Germany were both cut from the same cloth – totalitarian states imposing their demands on smaller states by force of arms.

In the case of the extreme right, the enemy of Finland was also perceived as God’s enemy that should be destroyed so that Christian values would survive in the world. This tendency was to be found in the right wing’s image of the Soviet Union before the war, but as the war continued it became a view that was more widely shared than previously. From January 1940 on, when more frequent Soviet air raids occurred despite the strong defence put up by the Ilmavoimat, the enemy’s inhuman cruelty was constantly emphasised in the news headlines. Editorials emphasised a parallel between the new attacks and the similar experiences of previous generations who had been attacked by the same archenemy. The labour newspapers’ condemnation of the Soviet air raids was ferocious from the first days of the war. However, neither the Russian national character, the Great Wrath nor the archenemy issue were brought up when deliberating the air raids. Instead, what was emphasized was the target areas of bombing and Stalinist imperialism. It was reported in labour newspapers that the Soviet Union for some reason bombed areas where workers lived especially intensively. The non-socialistic newspapers wrote about this also, but this view was clearly emphasised in the labour newspapers. From the background, one can see a desire to influence workers’ feelings at the moment of distress with concrete facts. Apparently there was no absolute certainty at the beginning of the war that the entire working class would fight to defend the country against the Soviet Union. A comparison with non-socialist papers, which did not need have a similar concern with regard to their readers, also emphasises the differences. The non-socialist newspapers for example, were able to concentrate on proving through history the cowardly nature of the enemy, which may not have appealed to the leftist readers of the labour newspapers.

When the concern for maintaining national unity turned out to be groundless as the war went on, the portrayal of the Soviet Union’s war as a war against civilians became more uniform. This changed viewpoint affected the labour newspapers most, as from January 1940 on they wrote more and more articles describing the Russians’ as barbarians as well as Russia being Finland’s traditional archenemy. These characteristics however never as prominent during the war as they were in the non-socialistic newspapers. The condemnation of the system created by Stalin and its differentiation from the “real labour” ideology would continue as a theme of the labour newspapers for the Winter War and thereafter.

As was stated at the beginning, appropriate slogans and terms that portray an enemy as evil are easy to adopt and are a common theme of war-time propaganda. In the Winter War, the Soviet Union made this an easy task for the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus. The enemy who bombed civilians became “Ryssä” in the right wing and agrarian union newspapers from the beginning of the war. The spirit of defence was intensified by stating that “one Finn equals twenty ‘ryssä’”. The opinion-uniting influence of the war grew stronger in January 1940 when there were strongly worded articles and editorials about “ryssä” in all the newspapers. At that time, even Pohjolan Työ, an extreme leftist labour newspaper, headlined its news of bombings with the emotional statement “Nearly 7000 kg of bread dropped last week by “ryssä’s” flying devils on top of civilians.” At the same time, news reports according to which the Soviet Union frequently bombed hospitals, churches and ambulances transporting the wounded became more common. The slogan ”A red cross equals a bombing target in the enemy’s mind” was headlined in all newspapers and made headlines in foreign newspapers worldwide.

“The Land of Kolkhoz Slaves and Forced Labourers”

After December, analytical articles in newspapers often examined communism, the Russian people, leaders of the Soviet Union and Soviet society. In non-socialistic newspapers, in which the abolition of private property, kolkhozes, the banning of religion and the communistic doctrine had already been described prior the war as the greatest evil, it was possible to write these articles in an I-told-you-so-tone. The Soviet system was as rotten and violent as had always been said, although a lot more was written with specific details of oppression, dictatorship and misery. Much was also made of the discovery of the “slave camps” on the Kola Peninsula, the discovery of the many mass graves, particularly along the route of the White Sea Canal and especially of the murders and deportations of Karelian Finns within the Soviet Union that was now reported on in great and shocking detail. As one can imagine, reporting and discussion of these topics in the newspapers intensified the already strong will of defence. In principle, one can summarise the image of Soviet society in non-socialist newspapers with a statement that, for these newspapers, the Soviet Union was the land of kolkhoz slaves and forced labourers led by Stalin, a bloody dictator and a mass-murderer who exceeded the worst excesses of Genghis Khan.

There were some differences in the viewpoints stated. For example, newspapers of the Agrarian Union wrote for their readers explaining the misery in the kolkhozes and the shortages of food rather more than other newspapers did. Religious persecution was also a part enemy image spelled out by the Agrarian Union and right-wing newspapers’ as well as in the entire non-socialist press. The negative characteristics of the Russian workers was mostly written about in the right wing and the Agrarian Union’s newspapers, with the Russians described as, for example, “an uneducated horde”, “a horde of slaves without their own will”, and “eastern barbarians”. Differences of emphasis were found mainly in giving reasons for the evil actions of the Russians. For the extreme right, they were due to the Russian people’s inherent characteristics. When we move toward the centre, the view is expressed that the Russians eval actions resulted more from a lack of education and centuries of oppression. At first, the descriptions of liberal newspapers also included pity for the oppressed people of Russia. This pity disappeared completely as the war continued. For example newspapers of the Agrarian Union begun to write that the Russian people were themselves responsible for their own misery because they were unable to establish a better system. In this view, one can also see the effect of the nationalistic Finnish ideology emerging.

The leaders of the Soviet Union were criticized so strongly that in February 1940 censorship forbid the making of defamatory comments about Stalin as a person. The background to this prohibition were articles where Molotov was commonly described as “molottaa” (says stupid things). Stalin was described as “a despot and tyrant”, “a bloody dictator”, “Josef the Terrible”, the “Russians’ new God” or as the “old bank robber”, who in his lust for power had his people killed in abundance. The articles in the labour newspapers about the Soviet Union were rather more studied and analytical than those of the non-socialistic papers. The Russian people were also criticized rather less frequently than in the non-socialistic newspapers. This may have been because of the situation of Finland’s leftists after the Russian Revolution and the Civil War of 1918. In the early 1930s, extreme leftist workers still had idealised views of the Soviet Union. Although this image had started to crumble as a result of events occurring in the Soviet Union in the later 1930’s, images are generally long lived and one may assume they had not entirely disappeared in the late 1930s.

As the war went on, it became clear that Finnish workers were as strongly committed as any other Finn to defending their country on the frontlines, and that the Soviet propaganda had no effect on them. Regardless of this, or partly due to this, there was a desire in the labour newspapers to criticise conditions in the Soviet Union. It was certainly easier to influence those who possessed a right-wing way of thinking and shared an image of the Soviet Union as the enemy, even during peacetime, by appealing directly to their emotional image of Russia as the traditional enemy and an evil Communist state. Workers, for their part, were generally not receptive to this viewpoint and as a result, facts were emphasised in creating the image of the Russians as an enemy.

In January, February and March 1940, labour newspapers’ often long editorials presented more and more information of the enemy country’s condition based on accurate numbers. The labour newspapers described the Soviet Union’s shortage of housing, food and consumer goods, how much a Soviet worker was able to buy with his salary and how much he paid in taxes. And, above all, there were continual reminders that the rights of citizenship that all Finns enjoyed – such as the right to go on strike – were missing, conditions were generally miserable, and there was a lack of personal freedom in factories and kolkhozes. Much was also made of the horrors of the slave camps that had been uncovered, and the sufferings of innocent people who were guilty of no crimes. These newspapers constantly sought reasons why the revolution had developed in entirely the wrong direction. Stalin was most commonly presented as the guilty party. He was said to have changed the system created by Lenin into a violent dictatorship, which subsequently destroyed Lenin’s co-workers. This viewpoint was understandable because it left honorably intact the Finnish labour movement’s roots, which dated to the period of the Russian Revolution and, thus, it did not include elements that violated traditions. As the war continued, criticism was also focused on Lenin, who was now thought of as the founder of an extremist Soviet Union. Apparently the Workers were no longer offended by this and it was possible for the ideologies between Finnish socialists and non-socialists to draw closer.

”David and Goliath: the Image of the Red Army in the Finnish Press”

From the very first, the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus had put a great deal of thought and planning into how the Red Army as an enemy was to be portrayed, both in the Finnish Press and to foreign correspondents and the foreign media. There was of course a great concern that in any war with the Soviet Union, the Finnish military would be severely outnumbered with all the military resources of a major totalitarian state attacking the small Finnish military. Initial Finnish strategy was geared towards a strategically defensive war in which the Finns would be fighting against far larger forces. News releases from Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus would continually emphasise this, and also emphasise the need for assistance – of equipment, weapons, munitions and men. The Red Army’s skills and size would be continually mentioned, always in conjunction with the fact that the Finns were holding the line, undefeated, inflicting large losses on the Red Army in every battle. The continuing tactical successes of the Maavoimat in almost every action was downplayed, as were the astounding ratio of Red Army casualties to Maavoimat casualties.

Within the Finnish Press, there was an emphasis on the strong defensive fight being put up by the Finnish military. Within a few weeks however, events overwhelmed the ability of the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus to impose their own “spin” on the stories being published. The mid-December 1939 defensive victory at Tolvajärvi, the truly enormous losses inflicted on the Red Army on the Karelian Isthmus, the limited but tactically highly successful counter-attack on the Isthmus of mid-December an the annihilation of the Soviet naval and marine force attempting to land near Petsamo were victories that the Finnish newspapers (and the foreign press) all emphasized. Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus was somewhat successful in ensuring that the Red Army’s mistakes and poor command were not emphasized, but with the stunning victories of January and February 1940 – especially the battles of Suomussalmi and Raate in early January, the slightly later capture of Murmansk and the rapid offensive in eastern Karelia that took the Maavoimat to the Syvari, Lake Onega and the White Sea, it was hard to portray the red Army’s military skills as anything other than sub-standard.

The emphasising of Finnish victories and the underestimation of the Red Army’s military skills was a view expressed in all Finnish newspapers, from late February on. Although Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus attempted to prevent newspapers from underestimating the enemy and overestimating Finnish victories, the right wing and the Agrarian Union’s newspapers and somewhat later all non-socialist newspapers were guilty of both. Many newspapers started to write that as a result of the war, the Soviet Union was more likely to collapse than Finland. When the situation of the time is taken into account, the description of the enemy’s poor military skills was discussed to some extent as an attempt to maintain the people’s will to fight, which may have been the real reason but was not really necessary. After all, Finland could not have been certain ar the beginning of the war that she was able to defend herself against a great power. The Soviet Union itself was prepared at most for a two-week war, which was a realistic assumption because nations such as Czechoslovakia, Austria and Poland had either surrendered without a fight to Germany or they had collapsed instantly.

Furthermore, there was no certainty in Finland when the war started as to whether Finland’s own ranks would remain intact. In January, the situation was completely different – Finland had not just stopped a great power cold, but had also inflicted such severe casualties that the entire world looked on with admiration and wonder. As a result, instead of becoming divided, the cohesiveness of the Finns became ever stronger. An overreaction in the propaganda war was perhaps the result of this feeling of relief – Newspapers, including many of the major newspapers, reported that the Soviet military leaders had left their troops without supplies, did not take care of the wounded, had men killed left and right and, ultimately, sent them to attack at gun point. Therefore, it was possible to imply that the Red Army was close to collapsing.

The defensive propaganda of the early war took on more offensive tones as the Finnish strategic position strengthened. With the May 1940 offensive that took the Maavoimat back down the Karelian Isthmus to the outer suburbs of Leningrad, the tone of Finnish reporting became ever more strident – although in foreign newspapers the Battle of France, followed by the fall of France, virtually eliminated Finland and the Winter War from the headlines. But by then at least, the information war fought by Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus had been, for all intents and purposes, won. Large foreign volunteer contingents were in Finland, weapons and munitions had arrived or were en route, foreign support was assured and Finland was able to fight on, logistically secure. Many of the non-socialist newspapers held the optimistic view that the Soviet Union was going to lose the war and face societal collapse – despite the best efforts of the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus to rein in this over optimistic train of thought. Newspapers of the Agrarian Union and the right wing were the guiltiest of underestimating the Soviet Union. Newspapers of the labour class, in which the Red Army’s good equipment and training were occasionally described, were the least guilty of this underestimation. Even this late in the Winter War however, there was occasionally worry about underestimation of the Red Army – particularly in the Social Democratic newspapers, which feared that the underestimation would eventually prove costly by making foreign countries believe that Finland did not need any help and that the enormous resources of the Soviet Union remained a threat.

Therefore Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus continually reminded the media that it did not matter how wretched a Russian soldier may be and how badly he was led. Finland was dealing with a great power that had at its disposal unlimited reserves, as opposed to Finland’s small numbers. Despite this, the huge Soviet offensive of July 1940 that stretched along the entire front, from the White Sea to the Gulf of Finland, came as a shock to those who thought Finland on the verge of victory. Instead of victory and a negotiated peace, Finland was once more fighting desperately for survival and strict censorship had to be imposed to avert panic-stricken reporting of defeats and attacks made with overwhelming strength. In the event, despite the size of the attacks, the tactical skill of the Finnish military resulted in a series of annihilating victories over the Red Army. The Finnish newspaper reports of the time all exude a feeling of relief rather than of triumph – it was realized how narrow the margin had been, with victory the result of the skill and courage of every Finnish soldier – and newspaper reporting tended to reflect this rather clearly. The elation and sense of victory of a few weeks before had rapidly turned to incipient panic and then relief and a realization that getting out of this war was going to be just as much a strategic battle as winning the fighting so far had been.

At the same time as the Red Army attacked the Finns, Stalin had also decided to deal with the incipient problem of Estonia and a further massive offensive had simultaneously been launched against the Estonian armed forces. The five divisions of the Estonian Army together with the Estonian Air Force had put up a gallant resistance but found themselves driven back by sheer weight of numbers and firepower. The redoubt centered on Tallinn held out into late August 1940 but fell eventually – with a number of Estonian units fighting to the end to ensure as many civilians as possible could be evacuated to Finland. In this way, what amounted to personnel for two Divisions together with some 100,000 civilian refugees found themselves in Finland. This was reported with some sadness in the Finnish press – that the massive Red Army offensive that the Finns were facing precluded help from Finland being extended, other than from the Merivoimat, which carried out the evacuation from Tallinn under heavy fire (and later, from the islands of Osel and Moon). But it was only in the Finnish and Swedish Press that the situation of Estonia was reported extensively. In the rest of the world, a paragraph here and there was all that Estonia received. She would be forgotten for the next four years by all but the Finns.

The creation of the enemy image had succeeded rather too well

As a whole, Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus succeeded in its two-fold task of (1) influencing Finnish public opinion and maintaining the nation’s will to fight and (2) influencing foreign public opinion to generate support for Finland (which we will examine in the next Post).

Looking at Finnish public opinion, success was absolute – throughout the entire Winter War and thereafter, everybody in Finland felt that there was no alternative to fighting. Therefore, the readiness of the newspapers to maintain and support a “spirit of defence” existed across the entire political spectrum from the start. When we examine the image created of the Soviet Union, both the non-socialist and labour newspapers’ image of the Soviet Union was that Finland was dealing with a barbaric enemy. If the Soviet Union won, the enemy would not only conquer the country militarily, but would also destroy Finnish society, culture, religion and eventually the nation in its entirety. Each group of newspapers emphasised issues central to its own worldview. Therefore, details of the enemy image varied according to which issues were considered the most important in its own ideology. In point of fact however, the image became increasingly uniform as a result of the war and by the end of the war, those views that were originally held only by the right wing were adopted also across all other Finnish newspapers.

The image of military skill clearly shows how difficult it was to erase the self-admiration and, in reversal, the underestimation of the Russian enemy that emerged in January and February of 1940. The inferior enemy soldier as an archetype was created in Finnish newspapers without caution following the startlingly one-sided victories of the winter months. Thus when the major Red Army offensive of July 1940 burst against the Finnish defences, newspapers had succeeded too well in the creation of the image of the unskilled enemy and both the soldiers on the frontlines and the civilians at home were shocked at the resurgent strength of the Red Army. The attack began with a massive and successful Red Army crossing of the Syvari in late July, while a coordinated attack on the Karelian Isthmus was timed to coincide with the Syvari offensive.

Initially threatening gains were made against the greatly outnumbered Maavoimat. Within a week, the Maavoimat had recovered and launched a four-day counter-offensive, driving the Red Army forces on the Isthmus back past their starting point. Stalin ordered Timoshenko to continue the offensive across the Syvari, but after initial deep penetrations, further attacks were decisively defeated; after which the Maavoimat counterattacked at the seam between two Red Army groups, crossed the Syvari, and advanced southward and westward towards Leningrad in over a week of heavy fighting while inflicting enormous casualties. At the same time the Ilmavoimat launched wave after wave of strikes against Red Army, Soviet Air Force and infrastructure targets, flying a higher sortie rate than at any other time except the early weeks of the Winter War.

For months the Finnish newspapers had described the enemy as militaristically extremely incompetent, its leaders as tormentors of their own people, its society as being on the brink of collapse, and its people as a mere mob afraid of the dictator. So the Finns were not psychologically prepared for the Red Army’s July offensive. Newspapers, and through them, their readers were themselves prisoners of an image of an incompetent enemy created for domestic use – and, it must be admitted, based on the early months the Red Army was incompetently led and trained, but by late summer 1940 major improvements in the enemy could be seen and this was reflected in a substantially more cautious viewpoint in the media from August 1940 on. Thus, the destruction of the Kremlin and with it a large proportion of the Politburo in the Ilmavoimat strike of September 1940 was not greeted with the elation that earlier victories had resulted in. The response was rather one of caution – would this attack merely spur the Russian monster into a renewed fury, or would it, as Mannerheim gambled, result in a new leadership and hopes of a peaceful conclusion to a war that, for Finland, could at best be a draw.

We now know the end result – the triumvirate that succeeded Stalin negotiated a peace agreement with Finland, one that satisfied neither completely but was at least tolerable to Finland. There were concessions made on both sides, and later, due to the extreme secrecy under which the talks were conducted, there would be much criticism in Finland of the Peace Treaty. The common view was that Finland had won victory after victory and suffered tremendous casualties in a war that the Soviet Union had started – and had won very little from her victories. In addition, a deep and abiding hatred of the Russians permeated Finnish society from top to bottom. Therefore, the terms for peace became upsetting news for the whole nation. It was for this reason that Marshall Mannerheim presented the terms of the peace agreement to the people of Finland. As Finland’s military commander, the architect of victory, he was the most trusted person in Finland and it was certain that every Finn would heed his voice. As indeed they did.

This did not mean the people of Finland were happy with the terms of the Peace Treaty. In this, Finland had succeeded too well in her creation of the enemy image which had at first been far from uniform. But by the end of the Winter War, there was a common view shared throughout Finnish society that Russia was indeed the historic enemy, an evil empire, the Red Army were indeed “hounds from the steppe”. And thus, while a peace agreement had been signed, the Finnish newspapers were united as one in agreeing that Finland must remain on guard, her armed forces strong, ready to again protect Finland in a world at war.

Raja railona aukeaa (Like a chasm runs the border)

Edessä Aasia, Itä. (In front, Asia, the East)

Takana Länttä ja Eurooppaa; (Behind, Europe, the West)

varjelen, vartija, sitä. (Like a sentry, I stand guard)

Note on sources: The above is based largely on http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9514266331/html/t857.html (Image Research and the Enemy Image: The Soviet Union in Finnish Newspapers during the Winter War (November 30, 1939 – March 13, 1940 by Sinikka Wunsch, Oulun Yliopisto) but adapted for this ATL.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

One Response to What then of the Finnish Press and the Winter War?