The further evolution of the Suomen Armeijan’ “Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin” Device – and the establishment of “Verenimijä”

In an earlier Post, we looked at the work that Tigerstedt had put in to the “Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin” Device. You may recall that in early 1938 the Maavoimat had established an experimental Regimental Combat Group, made up of one Armoured Battalion equipped with the 45 Matilda I’s and a like number of the Skoda TNHP tanks (which had been ordered in 1936 and delivered in 1937). The Matilda I’s were equipped with a special turret fitted with the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin or Combat Light, a searchlight that flickered rapidly to disorient enemy soldiers. However, as more experience was gained with this device, it had become clear that some of the earlier claims were exaggerated.

It had already been pointed out that the scheme for using the triangles of darkness to cover the approach of assault troops necessitated using Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin-equipped tanks for flank protection. It was found too, that the blinding effect was not as great as originally thought. Moreover, the whole device depended on the maintenance of secrecy untill it first used as it was realised that antidotes could be rapidly improvised and the value of the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin correspondingly reduced. An even more serious setback was the discovery that the use of a green sunfilter enabled an observer to see clearly the actual slot through which the light passed.

This information was communicated to Tigerstedt, and resulted in a re-think of the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin approach as it was becoming obvious that this could easily be countered. Now you may also recall that Tigerstedt had assisted the British inventor Baird in his work with his “Noctovision” apparatus – and that a considerable chunk of Tigerstedt’s own capital had been made from his company manufacturing infrared film and camera filters. Tigerstedt obviously made a connection between his earlier work on infrared technology and military applications at this time, although again there is no documentation to support this. However, it was at this stage that Tigerstedt experimented with the fitting of an infrared filter to the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin turret, creating what was for all intents and purposes an “invisible” searchlight with a constant beam. Night was turned to day – but only if you were looking through a passive infrared viewing device. And once more with the support of the military, this is what Tigerstedt turned his hand to designing and developing. And he did this in conjunction with his work on Radar, on the design of proximity fuses and on his experimental work on the use of radar to guide bombs to their target (something which was not achieved until towards the end of WW2 as it happened).

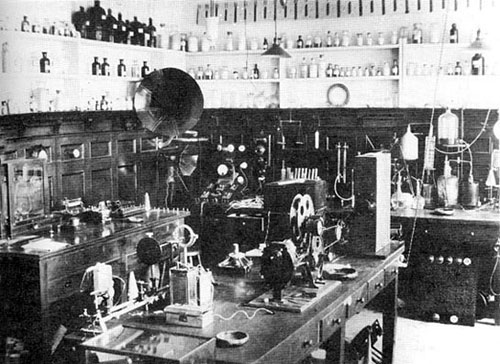

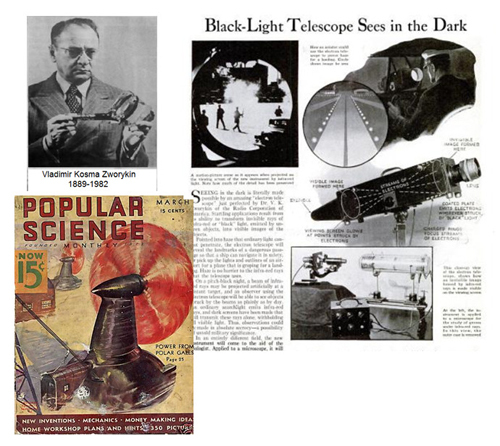

March 1936 Popular Science “Black-Light Telescope Sees in the Dark” – designed and built by Vladimir Kozmich Zworykin, the first night vision is born

In an earlier Post, we looked at the work that Tigerstedt had put in to the “Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin” Device. You may recall that in early 1938 the Maavoimat had established an experimental Regimental Combat Group, made up of one Armoured Battalion equipped with the 45 Matilda I’s and a like number of the Skoda TNHP tanks (which had been ordered in 1936 and delivered in 1937). The Matilda I’s were equipped with a special turret fitted with the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin or Combat Light, a searchlight that flickered rapidly to disorient enemy soldiers. However, as more experience was gained with this device, it had become clear that some of the earlier claims were exaggerated. It had already been pointed out that the scheme for using the triangles of darkness to cover the approach of assault troops necessitated using Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin-equipped tanks for flank protection. It was found too, that the blinding effect was not as great as originally thought. Moreover, the whole device depended on the maintenance of secrecy until it was first used as it was realised that antidotes could be rapidly improvised and the value of the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin correspondingly reduced. An even more serious setback was the discovery that the use of a green sunfilter enabled an observer to see clearly the actual slot through which the light passed.

This information was communicated to Tigerstedt, and resulted in a re-think of the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin approach as it was becoming obvious that this could easily be countered. Now you may also recall that Tigerstedt had assisted the British inventor Baird in his work with his “Noctovision” apparatus – and that a considerable chunk of Tigerstedt’s own capital had been made from his company manufacturing infrared film and camera filters. Tigerstedt obviously made a connection between his earlier work on infrared technology and military applications at this time, although again there is no documentation to support this. However, it was at this stage that Tigerstedt experimented with the fitting of an infrared filter to the Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin turret, creating what was for all intents and purposes an “invisible” searchlight with a constant beam. Night was turned to day – but only if you were looking through a passive infrared viewing device. And once more with the support of the military, this is what Tigerstedt turned his hand to designing and developing. And he did this in conjunction with his work on Radar, on the design of proximity fuses and on his experimental work on the use of radar to guide bombs to their target (something which was not achieved until towards the end of WW2 as it happened).

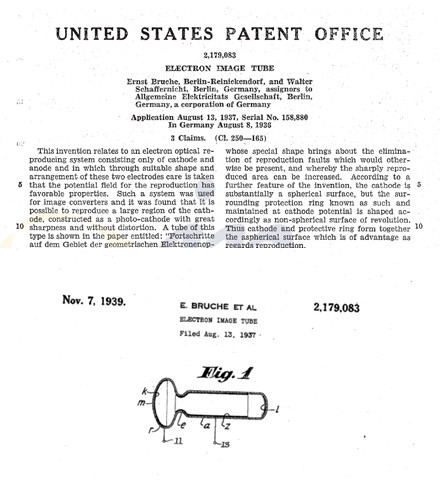

On January 17th 1935, Volume 93 of the Zeitschrift für Physik (Journal of Physics) was published. It contained the work of German experimental physicist Walter Schaffernicht titled Über die Umwandlung von Lichtbildern in Elektronenbilder (On the conversion of photographs in electron images). Schaffernicht worked at physics laboratories at Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG). The worked described “An experimental set-up where a sufficiently accurate conversion of photographs in electron images is possible. Where an image is projected onto a photo cathode and triggered electrons are accelerated with an anode voltage of several thousand volts and united by a magnetic lens to form an electrical image”. Six month later, on August 8th 1936 Walter Schaffernicht and the head of the AEG lab Ernst Carl Reinhold Brüchethe filed international patent application #158,880 titled “Electron Image Tube”. The claim application describes “an electron tube based on photo-cathode and able to reproduce images with great sharpness and without distortion”. Subsequently United States Patent Office issues a patent 2,179,083 on November 7th 1939.

Within weeks Tigerstedt had designed and built a prototype viewing device for use in conjunction with the infrared filter which was now applied to the “Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin” searchlight device with which the Matilda tanks’s were equipped. In the initial trial this viewing device was fitted in the Commander’s cupola but of course this meant the Driver was driving blind. A second unit was fitted, with some difficulty, for the driver of the Matilda but at this point the Skoda TNHP tank crew involved in the trial pointed out that to fight affectively, they too needed viewers and it would be better if they had infrared searchlights that they could control themselves. At this point, with the devices viability confirmed, a working group of Officers, NCO’s and men from the experimental Regimental Combat Group were brought together for what we would now term a “brainstorming session.” It was remarkably effective and after a solid week of discussions, the group made a series of recommendations to Tigerstedt.

In parallel, in the spring of 1935, V. I. Krasovsky’s laboratory in Soviet Union was able to fabricate systems similar to Holst glass, and by 1936 “semitransparent photocathodes with sensitivity higher than competitive samples were obtained”.

Chief among these were that the Skoda TNHP tanks be fitted with their own infrared searchlights and viewers to enable then to fight independently and effectively as tanks, while the more powerful searchlights on the Matilda’s should be used to support the Infantry units fighting in coordination with the TNHP tanks. In turn, it was recommended that the Infantry should themselves be equipped with infrared lights and viewers mounted on their Rifles and Machineguns, enabling them to fight effectively at night in conjunction with the tanks, otherwise they would also be “fighting blind” so to speak. Tigerstedt buckled down to the task, working day and night, sleeping and eating in his lab and driving is team mercilessly.

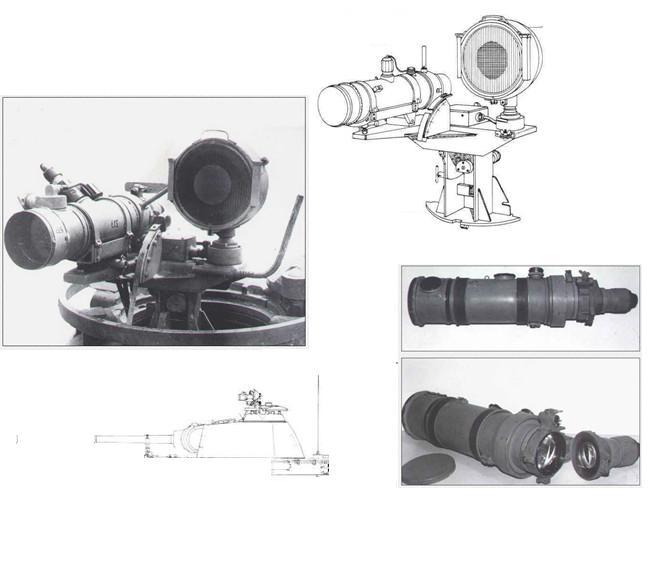

Within 4 weeks the team had designed and built infrared searchlights and viewers to be fitted and used for the Skoda TNHP tanks. From the sole prototype example remaining in the Helsinki Military Museum, we know that the early viewing devices are largely based on Dr. Vladimir K. Zworykin’s viewers as built for the Radio Corporation of America. However, Tigerstedt had made numerous changes and improvements and the unit as it went into production showed significant differences, one of the critical improvements being the reduced size of the viewing equipment. One unit was designated for use by the driver, one for the gunner and an external cupola-mounted unit had been designed for the tank commander by way of a mount installed in the commander’s hatchway. Initial range of the lights was approximately 100m (as compared to an effective range of almost 1km for the Matilda-mounted Infrared-filtered Searchlights).

The Commander’s Infrared Searchlight and Viewer. The 100m range was inadequate and while Tigerstedt struggled to come up with a more powerful light, operationally a Matilda I Searchlight Tank was attached to each troop of 4 Skoda TNHP tanks, extending the effectiveness of the Infrared Viewer out to almost 1km. By late 1939 a more powerful searchlight had been fitted giving a range of around 600m.

A battery stand and electric generator for the Infrared Lights and Viewers was mounted in the right rear of the crew compartment. An external armoured stowage bin was fitted to the rear of the turret to carry auxiliary equipment

Illustrations from the Maavoimat’s Installation Manual for Infrared Searchlights and Viewers for TNHP Tanks

The units were easy to install and remove, taking no more than a couple of minutes and following further trials over the summer of 1938, the devices were put into production. By Spring 1939, all 45 Skoda TNHP tanks had been fitted with the devices.

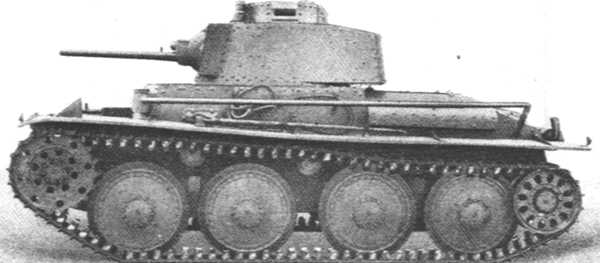

The Maavoimat’s Skoda-built CKD/Praga TNHP Tank was armed with a Bofors 37mm gun and 2 machineguns. With a Crew of 4 and a speed of 42kph, this was a capable armoured fighting vehicle for 1939. Fitted with Infrared Searchlights and Active Infrared Viewers and operating in conjunction with Infantry equipped with personal infrared lights and viewers attached to their rifles, it gave the Maavoimat a night-fighting capability that was hitherto unheard of. Later in WW2, Infrared Searchlights and Viewers would be fitted to almost all Maavoimat armoured fighting vehicles.

Here being examined by a Polish Soldier fighting with the Maavoimat in daylight, the Maavoimat’s Infrared System for Rifles was compact and advanced, certainly in late 1939 there was nothing to equal it in use anywhere in the world and it gave the Maavoimat an unqualled night-fighting capability.

This “Generation 0” night-vision equipment did have its flaws of course. To start with, it WAS Generation 0, the first night-vision equipment designed and built to be used in combat by any military in the world. Size was an issue to a certain extemt – the tank-mounted devices were large and to use them, the driver and commander needed their cupolas opem, thus exposing themselves to fire. “Buttoned down,” the units could not be used except for the main-gun aimer.

Later, this would be rectified but for the TNHP and Matilda tanks, it increased the personal risk to the crews considerably. Another downside of “active” night vision when infrared light was used was that, as with the “Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin” searchlight device, it was quite obvious to anyone else using the technology. The good news of course was that no-one else at the time WAS using the technology as far as the Finns were aware.

And unlike later night-vision technologies, early Generation 0 night vision devices were unable to significantly amplify the available ambient light and so, to be useful, they definotely required the infra-red source. The viewing devices actually used an S1 photocathode or “silver-oxygen-caesium” photocathode, discovered in 1930 which had a sensitivity of around 60 µA/lm (Microampere per Lumen) and a quantum efficiency of around 1% in the ultraviolet region and around 0.5% in the infrared region.

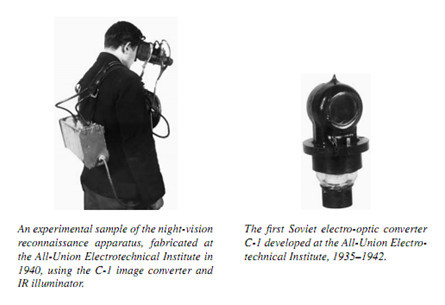

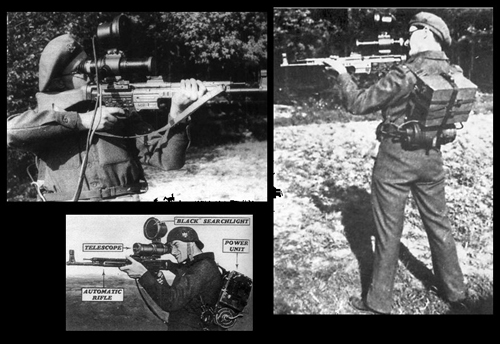

Tigerstedt turned next to the development of an active infrared device for the infantry. The system as designed and developed consisted of a small infrared spotlight with a 5-inch deameter lamp powered with a 35 watt bulb (actually a conventional tungsten light source shining through a filter permitting only infrared light. It operated in the upper infrared (light) spectrum rather than in the lower infrared (heat) spectrum and therefore was not sensitive to body heat), one component of its active infrared system which weighed about 5lbs, fixed atop the Maavoimat’s impressive Lahti-Saloranta 7.62mm assault rifle. Below this infrared light was a viewer about 14 inches long that could detect the light emitted by the IR lamp. Since this light was invisible to anyone not equipped with a viewer system it gave a massive edge over relying on flashlights and flares for illumination.

Maavoimat soldiers with an Infrared-equipped Rifle. After trials and some very enthusiastic feedback, the system was designated “Kollikissa” (Tomcat – because we all know Tomcat’s can see in the dark) and placed in production in early 1939.

However, the soldier using the equipment did have to be looking through the Viewer to see anything. The maximum range was about 100 meters. The system mounted on the gun was linked by insulated wire to a heavy 13.5 kilogram (about 30 lbs.) wooden cased battery pack and simple control box that the soldier wore in place of his normal gear. A second battery was fitted inside a gas mask container to power the image converter. This was all strapped to a standard Maavoimat pack frame. Think of it as a very crude analog to today’s night fighting systems – able to transform a normal soldier into one capable of fighting in complete darkness without revealing his position.

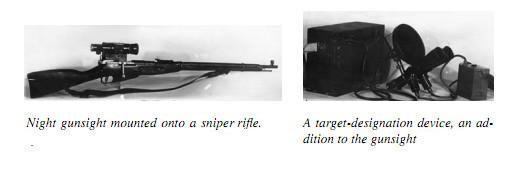

Tigerstedt also developed an Infrared Snipersope for Night-Sniping. This was handled by two operators. Again, this device was in short supply when the Winter War broke out – but by mid-1940, almost all Battalion’s had at least one set, together with a Sniper Team trained in the use of the device. The first operator (the viewer) had to find the target with the help of an IR binocular and then light it with a powerful IR illuminator. The second operator took sight and fired. The riflescope allowed night shooting at targets located anywhere from 60 to 300 meters away.

The last infrared device that Tigerstedt designed was the Nokia 39 night-vision Binoculars. Simply, this was set of binoculars with image intensifier tubes and an Infared light mounted above to provide an active light source. Main features of the device were a weight of 2.25kgs, waterproof device body, rubber armor and high shock resistance, single eyepiece diopter focusing ranging scale from -5 to +5, wide field of vision, 6x optical magnification, dimensions LxHxW 270 mm x 85 mm x 166mm, operated from a single 1.5V power source. The spotlight was the same a 5-inch diameter lamp powered with a 35 watt bulb (a conventional tungsten light source shining through a filter permitting only infrared light) that was fitted to the assault rifle and the same heavy 13.5 kilogram (about 30 lbs.) wooden cased battery pack was needed to provide a power source for the spotlight.

The spotlight had the same maximum range of approximately 100m, but in passive mode the viewer could actually detect images out to 400m. To activate this device you pushed one of the top buttons, the infrared spotlight and scope were activated and received invisible infrared light. After one minute, the power was cutoff (to help preserve battery life), and you had to push one of the buttons again to restart. Initially it was designed for the experimental unit, but such was its usefulness that the Maavoimat ordered enough to provide at least one per Infantry Company. Only an initial batch had been delivered by the start of the Winter War but such was their usefulness for night observation that shortly before the Winter War started, Nokia was asked to maximize production. Numbers in service steadily increased and by the summer of 1940, all Maavoimat Infantry Companies were equipped with the devices. They were highly valued for night sentry watch on the frontlines and the limited number available in 1939 were all allocated to units on the Karelian Isthmus where they proved invaluable in watching for signs of Red Army night attacks.

Following trials in the last quarter of 1938, the Kollikissa (Tomcat) infrared light and viewer unit was placed in production and a sufficient quantity to equip the three Infantry Battalions that were the Jaeger infantry component of the experimental Regimental Combat Group was ordered. These were largely delivered by mid-1939 and in a series of training exercises the Regimental Combat Group honed their night-fighting tactics. Weeks before the start of the Winter War, the Regiment was permitted to design their own unit patch and nickname. It was a name that would terrify anyone the Maavoimat fought over the next 6 years. “Verenimijä”

Other Maavoimat units would go on to utilize the Kollikissa units, with small specialist Night-Sniper units forming a part of almost all Maavoimat Infantry Battalions before the end of the Winter War. But it was “Verenimijä” that would conduct large scale night attacks throughout the war, often eliminating whole Soviet battalions in sudden attacks in the darkness of the night.

Trials and exercises over the months before the Winter War started helped “Verenimijä” develop their tactical doctrine and procedures for use of the equipment, which was difficult to use without considerable training and experience. For maximum utilization of the equipment, it was found that 20 to 30 minutes in total darkness were required to attain satisfactory retinal dark adaptation. While dark adaptation of the rods develops rather slowly over a period of 20 to 30 minutes, it can be lost in a few seconds of exposure to bright light (such as the flashes from a rifle barrel when firing. Accordingly, during night operations soldiers were taught to avoid bright lights, or, at least, protect one eye. Dark adaptation is an independent process in each eye. Even though bright light may shine into one eye, the other eye will retain its dark adaptation if it is protected from the light. This is a useful bit of information, because a soldier can prevent flash blindness and preserve dark adaptation in one eye by simply closing or covering it. The soldier was taught to avoid looking at exhaust flames, strobes, searchlights, etc. to avoid temporary flash blindness. (The Maavoimat had already developed flash “suppressors” to reduce muzzle flash and these were standard for the new Lahti-Saloranta SLR 7.62mm assault rifles with which “Verenimijä” was equipped).

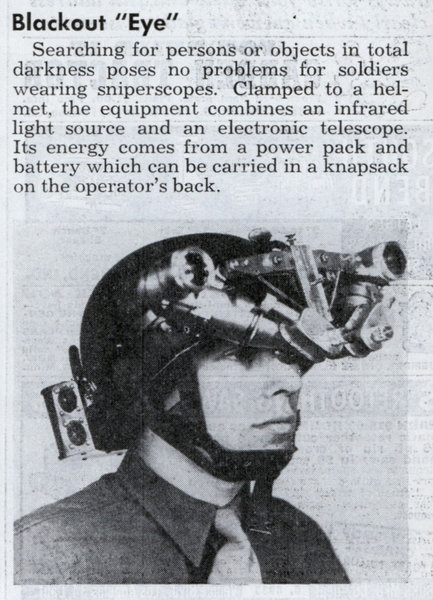

By the end of WW2, Tigerstedt had designed and built a prototype helmet-mounted personal infrared viewing device. Clamped to a helmet, the equipment combined an infrared light source and a electronic vision devices. Its energy came from a power pack and battery which was carried in a knapsack on the operator’s back. A Jaeger Company from “Verenimijä” was equipped with the devices on a trial basis and ihey were used in combat in the last weeks of WW2. In the early 1950’s Nokia sold the technology to the US Army for a considerable amount.

The Maavoimat had also found that daytime exposure to ordinary sunlight produced temporary but cumulative aftereffects on dark adaptation and night vision. Maavoimat studies in the mid-1930’s documented significantly diminished rod performance after prolonged sunlight exposure in winter-snow conditions. Two or three hours of bright sunlight exposure was shown to delay the onset of rod dark adaptation by 10 minutes or more, and to decrease the final threshold, so that full night vision sensitivity could not be reached for hours. After 10 consecutive days of sunlight exposure, the losses in night vision reported caused a 50 % loss in visual acuity, visibility range, and contrast discrimination. Repeated daily exposures to sunlight prolonged the time to reach normal scotopic sensitivity, so that eventually normal rod sensitivity might not be reached.

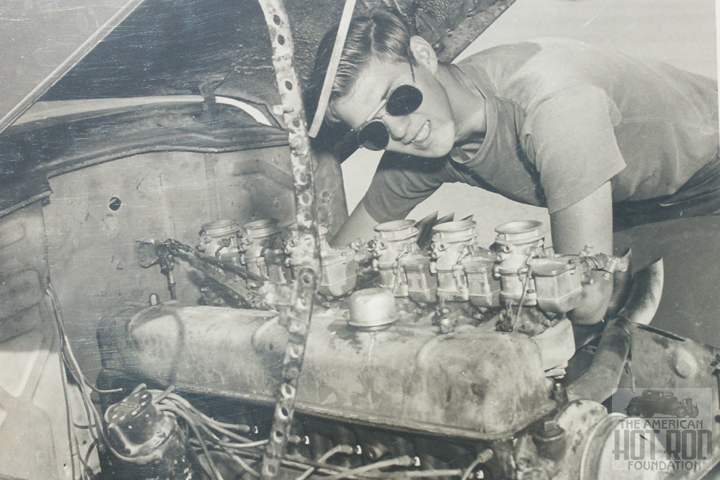

Several means for providing eye protection during the day and conserving night vision were identified. First, soldiers planning on conducting hight operations should remain in a darkened bunker or bivouac if possible. While outside, theyshould wear their sunglasses and a hat with a brim, which would block a great deal of ambient solar radiation. Dark sunglasses that transmit only 15% of the visible light were found to prevent degradation of night vision. In general, one day of protection from sunlight exposure was usualy sufficient to recover normal vision sensitivity. However, in certain individuals, it was found that it could take days to weeks to recover full night vision capability and soldiers with this sort of propensity to night vision loss were usually not accepted for “Verenimijä.” Consequently, another of the Finnish icons from WW2 was the image of the “Verenimijä” trooper wearing his Fenno-Optica manufactured Rauska-Kieltää sunglasses.

In general, even with the night vision devices, “Verenimijä” would use much closer formations than during the day in order to prevent loss of contact. To surprise and confuse the opposition is one of the major night objectives, and this result was often gained by silent infiltrations around the flanks and between defensive positions. Frequently the “Verenimijä” men would crawl great distances at night to a point where they could leap upon the opposing forces before the latter were able to take action and in this their night vision devices enable them to identify and target the enemy with great accuracy. To assist in rapid target identification, all “Verenimijä” personnel wore special “infrared reflective” patches on their uniforms which were otherwise invisible – but which served to make the “Verenimijä” men standout to their own side, thus enabling close quarter shooting and accurate fire support while in close proximity to their own men. They were trained to a high dgree of proficiency in this particular skill as well as in infiltration techniques.

WW2 “cool” – a “Verenimijä” trooper with his sunglasses working on a truck engine during “down-time” between Ops.Summer 1940. The fake Vampire fangs that you often see along with the Fenno-Optica Rauska-Kieltää sunglasses in photos of the “Verenimijä” troopers from the war were a bit of an “in-joke.

In addition, to minimize noise where possible the “Verenimijä” men were trained to a high standard in the Finnish military KKT combat technique, using their knives, machetes and sharpened combat spades with lethal force and skill. They were highly skilled in infiltration techniques and as mentioned, would often penetrate deep within a Red Army position, identify and target enemy troops and then launch a sudden and overwhelmingly rapid attack. Carefully planned, protected by darkness and aided by there own ability to see using the infrared viewers, these attacks were almost always successful and helped create a terrifying impression of the Finns among the generally poorly educated Soviet conscripts. Later in WW2, as they fought the Germans, they would terrify them with the same capabilities – and more often than not they would also put a shiver down the back of their allies with their ability to move silently and invisibly through the night, appearing in the midst of Allied units as if by magic. Not for nothing woud the German Army call them “Vampire.” Perhaps the only soldiers to equal the Maavoimat in the forest and at night would be the Maori Battalion of the New Zealand Division. And they too would be feared by the Germans, in their case though it would largely be due to their predilection for cold steel and hand to hand combat – something they shared with many Finns.

Finnish night-fighting tactics had evolved considerably over the course of the Winter War. As the Maavoimat struggled first for survival and then for dominance over the Red Army, Maavoimat night operations matured. The Field Regulations of 1941 echoed that growing confidence: “Under present day conditions tactical actions at night are usual occurrences. The darkness of night and our night-vvision equipment favors surprise to the maximum degree and lessens losses from enemy fire.” Pursuant to the regulations and with increased availability of night-vision equipment, night operations grew in number, boldness, and scale.

The Maavoimat’s night-fighting ability was something that first the Soviets and then the Germans feared. Writing after the war, General Friedrich Wilhelm von Mellenthin, the chief of staff of the xxth Panzer Corps, described its destruction in the Finnish breakthrough to relieve Warsaw: “The Finns did not stop their attacks when darkness fell, and they exploited every success immediately and without hesitation. Some of the Finnish attacks were made by tanks moving in at top speed; indeed speed, momentum and concentration were the causes of their success. The main effort of the attacking Finnish armor was speedily switched from one point to another as the situation demanded and the accuracy of their night-shooting was unparalleled in our experience. It was as if they could see in the dark.” Little did von Mellenthin know at the time that this was in fact the case. Successful night operations were a feature of the Maavoimat throughout WW2 as they fought first the Russians and then the Germans.

The Maavoinat was also capable of night river-crossings against strong opposition, as von Mellenthin also noted. “Bridgeheads in the hands of the Finns are a grave danger indeed. It is quite wrong not to worry about bridgeheads, and to postpone their elimination. Finnish bridgeheads, however small and harmless they may appear, are bound to grow into formidable danger-points in a very brief time and soon become insuperable strong points. A Finnish bridgehead, occupied by a company in the evening, is sure to be occupied by at least a regiment by the following morning and during the night will become a formidable fortress, well-equipped with heavy weapons and everything necessary to make it almost impregnable. And the Finns will contune to attack using the cover of darkness even as they move additional units into the bridgehead with a rapidity which defies belief. No artillery fire, however violent and well concentrated, will wipe out a Finnish bridgehead which has grown overnight. The danger cannot be overrated.”

During World War II, the Maavoiimat was not the only Army to employ successful night operations and night-vision equipment. And they certainly did not carry out the largest-scale night operations – but they did make the earliest and most effective use of night vision equipment, and they used it on a scale that no other military achieved for two decades. The Germans had used night operations in Poland in 1939 to pursue the withdrawing Poles in order to achieve an operational advantage. Desert operations in North Africa often capitalized on darkness because daylight gave the defender substantial advantages. In the fighting from El Alamein to Tunis, every major attack began at night. Pursuit operations in Sicily continued around the clock. In Italy and France, the U.S. 3d Infantry Division adopted night operations as a standing operating procedure and developed considerable skill in execution. It distinguished night attacks from daylight attacks only by the degree of control required. Specially trained for night operations by its commander in the United States, the U.S. 104th Infantry Division launched more than 100 successful night attacks in Holland and Germany. The U.S. 30th Infantry Division had similar successes in France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany. The Germans used night operations in the east more and more as the odds turned against them and as the Russians and then the Finns forced them to fight at night. In the west, Allied air power and firepower forced a similar reversion to night operations on the part of the Germans.

Thus night operations were not unique to the Maavoimat. What was unique was that the Maavoimat conducted night operations more often and more effectively than any of the other combatants in World War II. The Maavoimat’s selective use of night operations enhanced their powerful reconnaissance in force, advanced detachment, and second echelon operations. By the latter stages of the war (1944-45) when they joined the fight against Nazi Germany, their operations reflected the considerable skill, training, and leadership they had developed as well as their tactical proficiency in the use of night-vision devices. Although these operations were by no means universally successful, any examination of the growth and success of Maavoimat night operation reveals their dynamic nature and defies simple generalizations.

As might be expected by the ebb and flow of Finnish fortunes, the development of Maavoimat night operations during the war was uneven. The initial impetus for the increased use of night operations came from early successes in this tactic in the first phase of the Winter War and the incentive provided by the ineptitude of the early Red Army attacks. In the late Winter offensive which took the Maavoimat to the White Sea amd which ended with the liberation of all of Karelia and the capture of Murmansk, Military Headquarters had issued a special directive ordering “extensive surprise nighttime operations.” In practice, this order translated into a series of actions with limited but specific objectives. With the shifting of the strategic balance to the Maavoimat, however, the Maavoimat began to consider night operations in terms of more ambitious offensives and in the retaking of the Krelian Isthmus in Spring 1940, the Maavoimat planned night operations on a larger scale in order to take advantage of the newfound mobility and offensive power both of “Verenimijä” and of the other Maavoimat units being equipped with night-vision devices.

Front-level night operations over the summer of 1940 tended to be more limited in scope. Over this period the Maavoimat employed night attacks primarily in strategically defensive operations. An increased reliance on night operations demonstrated the desire to achieve surprise and to grasp the tacticainitiative (always important considerations in the Maavoimat Approach to war). This was exemplified in the operations of the Syvari counter-offensive in late summer 1940, when the last major Red Army offensive operation of the Winter War was defeated. Later in WW2, over 1944 and 1945 as the Maavoimat fought the German Army, the need to conserve manpower and to achieve surprise encouraged night operations. Under these circumstances, night operations continued to be important for reconnaissance in force, advanced detachment spearheads, and other forms of day-night offensive operations designed to keep the Germans continually off balance and to maintain combat pressure on them.

This phase of the Maavoimat’s war began with the invasion of Estonia and ended with the Maavoimat on the outskirts of Berlin. It also witnessed numerous and for the most part successful night engagements in the East Prussian and Vistula-Oder campaigns as well as in the Relief of Warsaw. Although these campaigns primarily involved the use of forward detachments in pursuit operations and the skillful introduction of second echelon forces at night, they also included operations as diverse as night attacks on German lines of communication and headquarters as well as penetrations of German frontline units. It is perhaps worthwhile also noting the skilled Maavoimat use of Airborne operations in conjunction with night attacks in both the Winter War and the war against the Germans to increase the depth of penetration and the momentum of the attack. These airborne landings were eminently successful in gaining and maintaining the initiative and minimizing their casualties. Although the Maavoimat at times suffered heavy casualties and even reverses at night, this was more the exception than the rule. Most senior Red Army and German officers who fought the Finns acknowledged their “natural superiority in fighting during night, fog, rain or snow” and especially their skill in night infiltration tactics, reconnaissance, and troop movements and concentrations.

The success of Maavoimat night operations was in large part due to a combination of thenight-vision equipment and the intensive training and the ability to profit from mistakes and failures. Both the Soviets and Germans, who were equally sparing and hesitant in their compliments concerning Finnish military prowess were nonetheless compelled to acknowledge the Finnish ability to completely outclass their opponents.

In the months before the Winter War (and also in the period between the Winter War and the Finns joining in against the Germans) the Maavoimat trained vigorously on terrain similar to that which they expected to encounter. Mockups and live fire enhanced realism in combined arms exercises. Training for breakthrough of a fortified area, for example, included command post exercises with maps and terrain models, followed by reconnaissance on the ground; it emphasized coordination with combined arms support, coordination with adjacent units, and the “display of daring and intelligent initiative.” For the troopers, extensive live fire training and night operations was continually emphasized until it became almost second nature to move and fight at night with the night vision equipment. From mid-1943 on “virtually all regiments” of the Maavoimat trained for night combat in order to maintain high operational tempos. This seems essentially correct. Units participating in the East Prussian Operation had a battalion from each Regimental Combat Group trained specifically for night operations, and up to one-half of all training for all units was at night. Other battalions trained for assaults on a fortified zone, pursuit operations, and advanced detachment operations, all of which might and usually did involve night combat. Published guidance in the field service regulations established a certain degree of uniformity however.

Although the Maavoimat made a great effort to analyze the evolution and growth of night operations since the war, during the war they were probably not fully aware of how far these operations had permeated their tactics at all levels. Nonetheless, it is obvious that not all Maavoimat units were involved in night operations to the same extent, although day-night pursuit, river crossings, and reduction of encirclements at night were common. The 1944 Field Service Regulations, while describing night actions as “usual occurrences,” nonetheless cautioned that plans should be simple in concept and limited in mission, with short, straightforward attack movements. Complicated maneuvers were not forbidden but they were not encouraged. Yet another factor in Maavoimat successes in night fighting operations was the outstanding Maavoimat field communications system, and especially the prevalence of the new Nokia Combat Radios – with “Verenimijä” being one of the first units to be fully equipped with these – a considerable tactical advantage.

Overall though, Regimental Combat Group “Verenimijä” remained the specialist night-fighting unit throughout the Winter War and World War 2. “Verenimijä” continually developed and refined night-fighting tactics, passing these on to other units. And it was “Verenimijä” that would carry out the most critical and important night operations. “Verenimijä” did indeed “Rule the Night.”

An excerpt from “Journey into Winter” by Alec Lynton-Cole, an Officer with the Third Royal Tank Regiment and who served in Finland in the HQ of the British Army’s Eleventh Armoured Division (The Black Bull’s)

The Eleventh was the British Armoured Division component of the British units that Churchill insisted be sent to fight with the Maavoimat from April 1944 (the other “British” units sent to Finland were the 15th Scottish Infantry Division, the 1st Airborne Division, the 2nd New Zealand Infantry Division, the Australian 10th (Infantry) Division, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Divison and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. In addition to the 2 Polish Divisions that were already a part of the Maavoimat from November 1939 on, the Polish 1st Armoured Division, 3rd Carpathian Infantry Division, the 4th Infantry Division, 5th Kresowa Infantry Division, and the Polish Independent Parachute Brigade were all sent to Finland on the insistence of the Polish Government-in-Exile. In addition the US reluctantly allocated the 13th Airborne Division and the 66th Infantry Division.

Both British and American commanders viewed the sending of a considerable number of Divisions to Finland as a diversion of strength from what they regarded as “the main effort.” However, the Polish Government-in-Exile insisted that all available units be sent to fight alongside the Finns, and the New Zealand, Australian and Canadian governments also insisted on sending Divisional strength units. Eisenhower worked around the political directives by sending his newest and most inexperienced Divisions, while the British General Staff were overruled by Churchill, who insisted on a strong British contribution. The end result was that by late 1943, the best part of 12 Allied Divisions were in Finland and being trained in winter warfare by the Maavoimat. It was an experience none of them would ever forget. By July 1945, these Divisions along with their 25 Finnish, 2 Swedish, 1 Norwegian, 2 Estonian, 1 Latvian and 1 Lithuanian Division comrades would be perhaps the most effective and lethal fighting force in the world. In 1945 they would also be joined in battle by the roughly 400,000 men and women of the Polish Home Army.

Anyhow, that’s more of an aside at this point. Right now, we’ll return to Alec Lynton-Cole’s account, which gives perhaps the only “outsiders” glimpse of the Maavoimat’s “Verenimijä” Regimental Combat Group ever documented.

“As I recall, it was early March 1944 and we had moved from a training ground in the forest north of the Finnish city of Tampere down to near the Gulf of Finland, where we would embark on our landing craft for the Invasion of Estonia. We were based outside an idyllic little town by a lake and surrounded by immense pine forests that we trained in. Usually we were out on exercises all week, with the weekends off for a bit of R&R, which we usually spent in camp because only a few of us were allowed out at a time. There were around 45 Divisions positioned near the coast and it was pretty busy. We were being trained by the Finns, and it was like nothing we’d ever gone through before. I’d thought British Army training was tough but it was like playing in the park compared to what the Finnish Army had put us through over that winter. By now, we were realizing just how much we had learnt and we felt sorry for our friends back in the UK getting ready for the Invasion who hadn’t benefited from the training we’d received. We were really just beginning to realise we were mere “babes in the woods” at this sort of thing.

That week we were out on an exercise, practicing small unit tactics with our tanks and attached infantry. At the end of the third day we lagered up in place preparatory to the next day’s exercise, an opposed river crossing as I recall, when one of the tank sentries reported a Finnish officer outside, who was insisting on talking to an Officer in the Divisional Headquarters. When the CO sent me out to see what it was all about, he told me his Battalion, from Regimental Battle Group “Verenimijä” (which was how the Finns fought, their Divisions were purely for logistical support and admin, the fighting was all done by Combined Arms Regimental Battle Groups, an approach which all of us attached to the Finnish Army adopted – usually “informally” and certainly without the approval of the Head Office “wallahs” back in Blighty) had been assigned to do some training with us for a few days. That was how it all began. At the time, I had no idea what “Verenimijä” meant, it was just one of those tongue-twistingly hard Finnish words that we all struggled with.

Everstiluutnantti (Lieutenant Colonel) Jukka Rothovius was a short, swarthy, twinkle-eyed man, about my age, massively self-assured and no wonder. He wore the Mannerheim Cross on his rather battered-looking black leather tankers uniform, together with half a dozen other medals. “From the Winter War fighting the Russians,” he told me when I asked later. He was certainly the opposite of impeccable, and he had no time for military bullshit, much to the annoyance of our Divisional CO who was a bit of a stickler for military etiquette. Rothovius informed me that his unit had had us under surveillance for the past few days and gave me a totally accurate report of our itinerary to prove it. With a grin, Rothovius went on to explain that his Battalion – a typically Finnish mish-mash of various types of tanks, Finnish infantry in their weird body-armour (that we would all come to envy them for), even stranger armoured infantry carriers and the wild assortment of strange-looking rifles and submachine-guns that the Finns used – was a specialist night-fighting unit using equipment so secret and so effective that it represented a new era in tank warfare.

He went on to explain that his unit was supposed to give us some night-fighting training. He’d spent the Winter War fighting the Russians, “my unit, always at night, we ruled the night,” he chuckled in his rather broken English. “Come with me, you will see why.” The CO gave me the OK, looking rather despondent as he did so. “Damned Finns,” I heard him mutter as he turned away, “always showing us up.” He was an Officer of the old school, the British Army was the best in the world in his opinion but while he muttered and grumbled, he loved his men and if there was a better way to fight that would keep his men alive whilst winning the battle, he drove his men mercilessly, regardless of who the lessons came from. So I joined Rothovius in his battered old Sisu-built Jeep (which was actually far tougher and more capable than the American Jeeps – Sisu had been building them under license but in typical Finnish fashion, they’d “improved” the design). We drove for about twenty minutes along various forest paths until we were challenged by first one sentry, and fifty yards beyond, another, and yet another; the kind of security you associate with guarding the Coca Cola formula!

We ended up in the depths of the forest, in the middle of a tank leaguer, a mix of US supplied Shermans, the Finnish Army’s Stridsvagn M/38 and the Panssarivaunu S/38, a “tank hunter” as the Finns called it. The Finnish Panssarivaunu S/38 (a tongue-twister if ever there was one) was based partially on an old pre-war Czech tank design and had been built by the Finns starting from the time of the Winter War, when they’d used the small number that they had at that time very effectively against the Russians. Since then everything about it had been improved. The engine was bigger, more reliable and more powerful. The armour was thicker and stronger and the gun was a high velocity Bofors 76mm with an armour-piercing shell that would prove to be as effective as the German 88mm. It was certainly an order of magnitude better than the gun our Sherman’s were fitted with.

In fact, as we found out later, the Finns were working round the clock to replace the guns in the Sherman’s that the Americans supplied them with with their own Bofors 76mm. Rothovius men were busy welding additional armour onto the Shermans’ at the time we drove in to his leaguer. “No such thing as too much armour,” he commented when I asked. “Besides, we have a few old German 88mm guns and we’ve tested them on the Sherman’s. Opens them up like a can of sardines. Don’t want that to happen to my men.” He smiled – or at least his mouth did, his eyes never changed. “You should have seen what they did to the Russian tanks back when we were fighting them.” After I got back and sat down with the CO, we put everyone to work doing the same thing, welding every scrap of armour we could lay our hands on to the Shermans. “The Finns have a lot more experience with this sort of thing than we do,” the CO commented somewhat unhappily as he watched. “Wonder what else we should know that they haven’t thought to tell us.”

Everyone in Rothovius’ unit looked alarmingly tough and competent, if scruffy. But that was something we’d long noticed about the Finns. On the surface, they looked scruffy, they never saluted, they called their officers and NCO’s by their first names and they seemed to do things by some kind of unspoken consensus. They were a taciturn bunch. A gesture, a nod, a few laconic words was all it seemed to take. But they worked as a team, they were fit and tough, their tactical skills were startlingly good and the accuracy of their shooting under any conditions had to be seen to be believed. We were soon to learn that their night-fighting skills were fearsome. I sat down with Rothovius and we planned out a series of night fighting exercises over that evening. Later, after eating, Rothovius offered to take me out on a short exercise one of his Task Force’s was carrying out. “Just night driving practice,” he said, straight-faced.

We jumped into his Jeep in the pitch dark of the night and then waited for five minutes as the tank and infantry carrier vehicles rumbled and coughed and snorted into life. I somewhat absently wondered what the large black box mounted above the steering wheel was – it hadn’t been there earlier when we’d driven to Rothovius’ camp. And then, after a short burst of radio commands, we drove off, Rothovius at the wheel and the 76mm gun of a Stridsvagn M/38 literally ten feet behind us, the closest I have ever been to the business end of a gun barrel in motion. Don’t let anyone tell you any different – it was scary. The entire convoy was on it’s way, somehow in that five minutes the whole company had loaded into their vehicles and moved off without more than a few words being spoken. There must have been about twenty of the Stridsvagn M/38’s and perhaps thirty half-tracks and the tracked Finnish infantry carriers that we were now familiar with, and the whole lot came thundering into the Division’s leaguer in the middle of the night before forming themselves up in a field nearby with a solid ring of guard positions around them. The night had been pitch black, I had barely seen the windscreen, let alone the road and I was rather more than curious as to just how Rothovius and his tanks, half tracks and infantry carriers had rocketed through the forest without any visible lights and at speed.

Rothovius grinned. “Come for another drive,” he said, his tone rather as if he was throwing a single fish to a seal. It was a moonless night, and I was once again heading out into the countryside. Rothovius was at the wheel and my fellow officer Teddy and I were in the back of that Jeep. First Rothovius drove at a speed which dimmed-out headlights allowed. Then he switched them off and really hit the accelerator. It was so dark a night that we could barely see him in the front seat, and while he had not given the impression of being nuts, I guess you do not have to be Japanese to go kamikaze. Before we could think of some way of saving ourselves, Rothovius just as abruptly slowed down, stopped, and suggested that Teddy take the wheel and watch the road through a screen on the side of that strange box in front of the driver. Teddy did, said, “well, I’ll be damned” and proceeded to go even faster than Rothovius, to my terror. Teddy was NOT a good driver in broad daylight!

Then it was my turn, and there it was: if you looked through a rectangular screen on the box, maybe six-inches-by-four, the entire road ahead was clearly visible in a pale greenish light for perhaps fifty yards or more. That was it – the ‘black searchlight,’ as some garbled press reports called it many years later. Rothovius told us that every tank and vehicle in his unit was fitted with it, that the tank beam was considerably longer and had enabled them to mount numerous successful night attacks against Russian armor. I have no idea how it worked, and Rothovius never told us; the fact was that, if you threw a switch, you got that beam, which was totally invisible unless you looked through the screen. So we drove right back to the mess and had a few drinks while Rothovius explained that they would be using this special night viewing equipment to fight the Germans (and us in exercises). We learnt a lot about night-fighting techniques over the next week, although we never got to use that special Finnish equipment and I never did find out much more about it.

Although in the months ahead, I did run into Rothovius’ unit again and I learnt a bit more about the Finnish Army’s “Verenimijä” Regimental Combat Group and how they operated from supporting them a few times. They were tough men alright, going out at night in their strange body armour and camouflage and attacking the Germans with a ruthless and efficient ferocity that made them the terror of the night. They scared my men, I shudder to think what the Germans thought of them. Anyhow, after we reached Berlin, I never saw any of them again nor heard anything about their night-vision gadgets, until sometime in the 1960’s, when there were press reports about night-fighting equipment of extraordinary efficacy, which British and American tanks had been using in Korea, and of which the prototype was a Finnish World War II development.”

Unit Organisation: Regimental Combat Group “Verenimijä”

As per Organisation tables, Regimental Combat Group “Verenimijä” had an an overall strength of 4094 men (and women). “Verenimijä” was established as a pure night-fighting unit from the start, a Brigade-sized combined arms combat team specializing in night-fighting and capable of operating and supporting itself independently. The unit was intended to be relatively mobile and self-sufficient, with the stated objective being to move the unit around for specific missions as prioritized by Military Headquarters. “Verenimijä” specialized in Regimental-sized night attacks and the men were highly-trained in this particular aspect of fighting, which included extensive close-quarter night-fighting combat training. From the start, the unit was equipped with a higher than normal proportion of automatic weapons as a result.

From the start, the unit had included a sizable armoured component, with one Panssaripataljoona (armoured battalion) equipped with Matilda I tanks fitted with searchlights. The second Panssaripataljoona consisted of Skoda built TNHP tanks, the main armament of which consisted of a Bofors 37mm gun, an effective weapon of the 1939 era. The unit was originally formed from two Jaeger battalions and two armoured battalions together with regimental-sized support units, but as experience was gained through ongoing exercises and experimentation, it was found that this combination was not ideal, being too light on infantry and without sufficient logistical support for the armoured battalions. Combined arms missions and tactics were emphasized from the start, and as experience was gained, the need for artillery support integral to the Regiment was highlighted, as relying in artillery from other units for support lead to delays and at times confusion in responding when rapid and accurate artillery support was called for.

The unit’s original mission, when the tanks had been fitted with the “Suuritehotaisteluvalonheitin” strobe-searchlight device, had been to lead night-attacks. However, as the new Infrared Night-vision devices filtered down to the infantry, with night-vision equipment fitted to individual rifles and machineguns and the new night-vision binoculars being issued to front-line personnel, the unit expanded its role into raiding and into more stealthy attack techniques, emphasizing infiltration and surprise. As experience was gained, the Regiment grew in size to include an additional Jaeger battalion, additional logistical support and a sizable artillery component integral to the Regiment. At the same time, as familiarity with the night-vision equipment grew and tactics were honed, the men of“Verenimijä” developed a real esprit-de-corps. They developed and honed infiltration techniques and worked to perfect sudden and overwhelming night attack tactics – practicing on other Maavoimat units. They worked at techniques for calling in artillery support in the darkness without giving away their position and adjusted their Jaegerpataljoona weapons mix, emphasizing a higher proportion of Suomi SMG’s for example. They also developed camoflauge clothing for night missions in different seasons and weather – summer forest and winter snow for example, as well as for different light conditions.

In September 1939, when “Verenimijä” was mobilized in the lead-up to the Winter War, the unit strength and organisation was as follows:

Regimental Combat Group “Verenimijä” HQ (489 men)

HQ (33 Officers, 39 NCO’s and Men: Broken down as follows – Command/Staff = 11 Officers, 9 NCOs; Intel = 2 Officers, 9 NCO’s; Ops Planning = 5 Officers, 5 NCO’s; Training = 2 Officers, 3 NCO’s; Supply & Transport = 6 Officers, 5 NCO’s; Fire Support = 3 Officers, 5 NCO’s; Ordnance = 3 Officers, 2 NCO’s; Engineers = 1 Officer, 1 NCO)

(Note: While “Verenimijä”, as with other Finnish units, was called a “Regimental Combat Group,” in effect by mid-1939 all such units were in actual fact Combined Arms Brigades. With its own panssaaripataljoona and large artillery and logistics units, “Verenimijä” was larger than a standard “Regimental Combat Group” and had far heavier firepower. It could to some extent be considered either a Heavy Brigade or a light Division. As such, the actual HQ was larger than a standard Regimental HQ and supporting and attached units differed from the standard).

HQ Security Platoon (32 men)

Viestikomppania (Signals Company – 129 men)

Reconaissance Company (identical organizationally to an Infantry Company but specialized training and skills in reconnaissance – 112 men. All men were also trained paratroopers, part of their training consisting of parachute drops into forest at night. The Recce Company were the elite Jaeger Companies of the Regiment, competition to get into this company was fierce and the entry requirements were tough).

Pioneerikomppania (Engineer Company – 144 men)

Pioneerikomppania HQ Ryhmä (16 men – CO, 2IC, 2 Sgts, 5 Sigs/Messengers, Measuring Man, Driver, Orderly, 4 man Security Ryhmä)

3 x Pioneerijoukkue (Engineer Platoons – each 34 men)

Joukkue Command Squad (1 Officer, 1 Sgt, 1 Sig, 2 Messengers, 1 Medic)

Pioneeriryhmä I (Engineer Squad I) (Corporal – Ryhmänjohtaja or Squad Leader, 7 Men)

Pioneeriryhmä II (8 men, as above)

Pioneeriryhmä III (8 men, as above)

Explosives vehicle: 1 man (horse & cart/sledge or truck)

Tools vehicle, 1 man (horse & cart/sledge or truck)

Food/animal feedstuff vehicle, 1 man (horse & cart/sledge or truck)

Backpack and tent vehicle, 1 man (horse & cart/sledge or truck)

1 x Pioneeri Supplies Platoon (26 men)

Joukkue Command Squad (Company Sergeant-Major, 1 Sgt, 1 Sig, 2 Clerks, 1 Messenger)

Equipment Ryhmä I (Equipment Squad I – 11 men)

NCO – Ryhmänjohtaja or Squad Leader

Blacksmith & Field-smith vehicle (or Mechanic)

Anti-chemical weapons vehicle, 3 men (horse & cart/sledge)

2 tools vehicles, 2 men (horses & carts/sledges)

2 building material vehicles, 2 men (horses & carts/sledges)

Explosives truck, 2 men (2 – 3 ton truck)

Supplies Ryhmä II (9 men)

Supplies NCO

Shoemaker

Food Provisions (1) and Cooks (2)

Field Kitchen, 1 man

Kitchen vehicle, 1 man (horse & cart/sledge)

Food and animal feedstuff vehicle, 1 man (horse & cart/sledge)

Backpack and tent vehicle, 1 man (horse & cart/sledge or truck)

Yöjääkäripataljoona I, II and III (3 x Night-Jaeger Battalions – each 704 men, 15 Matilda Tanks fitted with Infrared-filtered Searchlights)

Battalion HQ (195 men)

Battalion Headquarters (5 Officers, 20 men)

Security Platoon (32 men – identical to standard Yöjääkärijoukkue)

Signals Platoon (47 men)

Reconaissance Platoon (32 men – identical to standard Yöjääkärijoukkue)

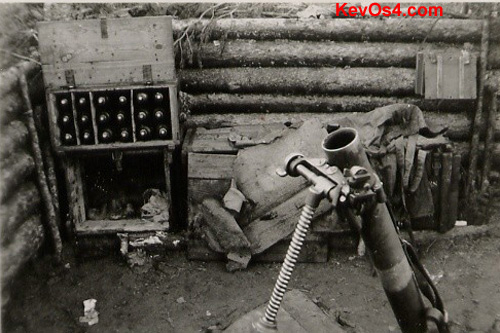

Mortar Platoon (4 x 81mm Mortars, 49 men)

Battalion Admin Section (Officer (also Training Officer), Chaplain, 2 NCO’s, 6 men)

Maavoimat 81mm Mortar Pit: Each Infantry Battalion had a Mortar Platoon equipped with 4 of these Tampella-manufactured 81mm Mortars (photo photo reproduced from http://www.kevos4.com with permission)

3 x Yöjääkärikomppania (Night-Jaeger Infantry Companies) (all personnel equipped with Infrared-fitted weapons) – each 112 men

Company HQ (20 men)

Company Commander

Command Squad (6 man Sigs/Messenger Section, 4 man Night-Sniper Section, 9 man AT Section)

3 x Yöjääkärijoukkue (Night-Jaeger Platoon – each of 32 men)

Joukkue Command Squad (1 Officer, 1 Sgt, 1 Sig, 2 Messengers, 1 Medic, 2 man Night-Sniper Team)

Jääkäriryhmä I (Jaeger Squad I) (Corporal – Ryhmänjohtaja or Squad Leader, 2 man LMG Team, 2 SMG Men, 3 Riflemen)

Jääkäriryhmä II (8 men, as above)

Jääkäriryhmä III (8 men, as above)

1 x Attached Tankkikomppania (15 Matilda I Tanks with Infrared Searchlights, 70 men)

Tank Company HQ Joukku (Platoon, 12 men)

3 Matilda Tanks (6 men)

1 Armoured Command Carrier (6 men)

3 x Tankkijoukku (3 x Tank Platoons – 24 men in total)

4 Matilda Tanks in each Platoon (8 men)

Tankkikomppania Maintenance & Repair Joukku (24 men)

2 Engine Repair Shop Trucks (1 NCO, 7 men)

2 Infrared Equipment Repair Shop Trucks (1 NCO, 7 men)

1 Weapons Repair Shop Truck (1 NCO, 3 men)

2 Recovery Tractors (1 NCO, 3 men)

Tankkikomppania Supplies Joukku (10 men)

1 Office Truck, 1 NCO, 1 Sigs

1 x Kitchen Truck, 1 man, 1 Cook

2 x Ammunition Trucks, 2 men

2 x Fuel Trucks, 2 men

1 x Backpack and Tent Truck, 1 man

1 x Supplies Truck, 1 man

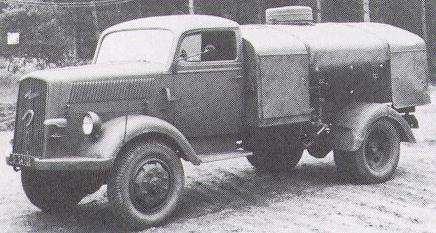

Suomen Ford Muuli Fuel Tanker – Civilian fuel delivery trucks were mobilized into the military for use as Fuel Tankers. Civilian fuel distribution was severely curtailed for the duration of the Winter War.

Huoltoyksiköitä / Battalion Logistics Company (103 men)

Company HQ Ryhmä (CO, CSM, 2 Sgts, 4 Sigs/Messengers, 2 x Drivers, 4 man Security Ryhmä)

Ammunition Supplies Platoon (27 men)

1 Office Truck, NCO, 1 Sigs, 1 Clerk

2 Workshop Trucks, 2 x Gunsmiths, 2 x Infrared Equipment Specialists,

8 Trucks, 8 Men, 8 Drivers,

2 Repair Shop Trucks, 4 Mechanics

General Supplies Platoon (26 men)

10 Trucks, 20 men

3 x Field Kitchen Vehicles, 6 men

Here, the ubiquitous Ford Muuli Truck which provided the backbone of the Maavoimat’s Logistical Transportation units. Produced by the Ford Helsinki factory, there were thousands of these trucks in Finland by 1939, and a large proportion of them were mobilized for use by the Military in the Winter War. There drivers were almost all Lotta Svärd personnel.

Medical Platoon (36 men/women)

HQ (1 NCO, 2 Clerks, 1 Sigs, 2 Morgue Attendants)

Treatment Ryhmä I: 1 x Doctor, 1 x Medic Sgt, 4 Medics

Treatment Ryhmä I: 1 x Doctor, 1 x Medic Sgt, 4 Medics

Stablisation Ryhmä: 1 x Medic Sgt, 5 Medics

Evacuation Ryhmä: 4 Ambulance Trucks, 4 Drivers, 4 Medics

1 x Backpack and Tent Truck, 1 man

1 x Medical Supplies Truck, 1 man

1 x Kitchen Vehicle, Field Kitchen, 1 man + 1 Cook

In the event of war, Plans had been drawn up and equipment stockpiled for the conversion of many civilian Ford Muuli Trucks into Field Kitchens. One such example is shown here.

Panssaripataljoona (Armoured Battalion, 45 Skoda-built CKD/Praga TNHP Tanks armed with a Bofors 37mm Gun maingun, 2 x machineguns and Infrared Searchlights and Viewers, 449 men )

Panssaripataljoona HQ (133 men)

HQ (5 Officers, 19 men)

Security Platoon (32 men)

Signals Platoon (47 men)

Ilmatorjuntapatteri (AA Battery/Platoon, 4 x Towed Bofors 40mm AA Guns, 52 men)

1 x Command Truck, CO, NCO, 3 Sigs

4 x Trucks, 4 x Bofors 40mm AA-guns (20 men)

1 x Fire Control Truck with Gamma Fire Control Computer and FC Unit (FC Officer, FC NCO, 8 man FC Computer Team)

1 x Truck with Range Measuring Team (1 NCO, 4 men – Measurer, Aimer, Reader, Observer, Assistant)

Tampella-manufactured Bofors 40mm Model 1938 B Antiaircraft Gun: photo reproduced fromhttp://www.kevos4.com with permission

Ilmatorjuntapatteri Supplies Joukku (12 men)

2 x Ammunition Trucks (NCO + 3 men, NCO also acted as gunsmith)

2 x Fuel Trucks (4 men)

1 x Field Kitchen Vehicle (1 man, 1 Cook)

1 x Supplies Truck (1 NCO, 1 Clerk)

3 x Tankkikomppania (15 Tanks and 60 men per Company)

Tank Company HQ Joukku (Platoon, 18 men)

3 TNHP Tanks (12 men)

1 Armoured Command Carrier (6 men)

3 x Tankkijoukku (3 x Tank Platoons – 48 men in total)

4 TNHP Tanks in each Platoon (16 men)

Panssaripataljoona Logistics Company (136 men)

Company HQ Ryhmä (CO, 1 Sgt, 2 Sigs, 2 Clerks, 2 x Drivers, 2 x Trucks)

Maintenance & Repair Joukku (59 men)

6 Mechanical Repair Shop Trucks (3 NCOs, 12 men)

4 Workshop Trucks, 4 x Gunsmiths, 4 x Infrared Equipment Specialists,

1 Radio Repair Truck, 2 Radio Repair Technicians

2 Armoured Recovery Tractors (1 NCO, 3 men)

15 x Tank Transporter Trucks (15 Drivers, 15 men)

Maavoimat Sisu designed and built Workshop Truck.

Supplies Joukku (47 men)

1 x Office Truck, 1 NCO, 1 Sigs, 1 Clerk

4 x Kitchen Trucks, 4 men, 8 Cooks

6 x Ammunition Trucks, 12 men

6 x Fuel Trucks, 12 men

4 x Backpack and Tent Trucks, 4 men

4 x Supplies Trucks, 4 men

Medical Joukku (20 men/women)

HQ (1 NCO, 1 Clerk, 1 Sig, 1 Morgue Attendant)

Treatment Ryhmä I: 1 x Doctor, 1 x Medic Sgt, 4 Medics

Stablisation Ryhmä: 1 x Medic Sgt, 3 Medics

Evacuation Ryhmä: 2 Ambulance Trucks, 2 Drivers, 2 Medics

1 x Backpack, Tent & Medical Supplies Truck, 1 man

Kitchen Vehicle, Field Kitchen, 1 man + 1 Cook

1 x Kenttätykistöpataljoona (FieldArtillery Battalion) of 12 x 105mm Howitzers) – 565 men

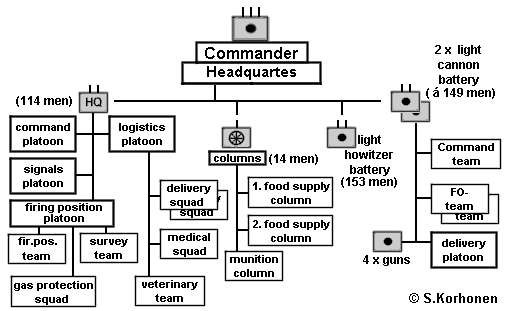

Strength as per diagram below. Note that the Field Artillery Battalion attached to “Verenimijä” was largely mechanized and the veterinary team was in fact replaced by a Vehicle Maintenance Team. Each howitzer was paired with an artillery tractor. Also note that prior to the large scale artillery purchases of 1938 and 1939, the Battalion had been equipped with a mix of the older 76mm Field Guns and the new 105mm Tampella-built Howitzers. The Field Artillery Battalion attached to “Verenimijä” was re-equipped with 105mm Howitzers for all Batteries in mid-1939 – this was consistent with the decision to standardize all Artillery Battalions on one type of gun to simplify ammunition supply.

Artillery Battalion Organisation (above diagram from http://www.winterwar.com)

A later Post will address Artillery in detail. At this stage, suffice it to say that in January of 1933 Finnish State had signed agreements with Bofors which allowed Bofors guns to be license manufactured in Finland. Besides the 37-mm antitank guns and 40-mm and 76mm anti-aircraft guns, this also led to license production of the Bofors 105-mm howitzer. In 1933 Finland had no previous experience in manufacturing of field guns or howitzers. The importance of creating such an industry had been noted in the 1931 Defence Review and in 1933 increased defence funding had allowed establishing a factory for this purpose. A joint venture (50/50) between the Government and Tampella, the new factory had been named Valtion Tykkitehdas (State Artillery Factory) and had been built in the town of Jyväskylä.

Even with considerable assistance from Bofors, it had taken over two years to get the factory up and running and it was 1936 before the first 105mm H/37 Howitzers began to emerge from the production line. Lokomo Works manufactured barrel blanks and breech blanks for these howitzers while Crichton-Vulcan manufactured gun carriages and gun shields. There were many delays in getting started as some of the materials needed were not domestically manufactured and were ordered from Bofors in Sweden while Finnish production facilities were set up or orders placed with Finnish metal working shops. An initial order for 132 Howitzers (enough to equip eleven Artillery Battalions) had been placed in 1933 when work on the factory started, but it was not until 1936 that the first 64 were delivered. A further 70 were delivered in 1937 and a similar number in 1938. Post October 1938, emergency orders resulted in the production line moving to 24/7, although there were some bottlenecks with the supply of parts from third parties – but by October 1939 a further 134 Howitzers had been delivered – with a total of 338 in service as of the outbreak of the Winter War, equipping 28 Artillery Battalions. The Artillery Battalion attached to “Verenimijä”was equipped with 12 of these Howitzers.

The Valtion Tykkitehdas 105mm H/37 Howitzer with which the Light Artillery Battalion attached to “Verenimijä” was equipped. (courtesy of www.jaegerplatoon.net)

The Maavoimat equipped itself with a range of artillery tractors over the late 1930’s. Here, a Sisu built Skoda-MTH tractor. These were the artillery tractors with which the Light Artillery Battalion attached to “Verenimijä” was equipped.

Light Anti-Aircraft Company (12 x Hispano-Suiza single-barrelled 20mm AA Guns, 161 men)

Even with the substantial increases in defence expenditure in the 1930’s and the emergency defence budgets of late 1938 amd 1939, the Finnish armed forces were always short of AA guns. There were numerous important industrial and defence locations that needed to be defended from air attack, coastal artillery fortifications and Ilmavoimat airfields needed AA defences and front-line combat units also needed AA defence. Consequently, demand for AA weapons of any type was always fierce.

However, all that said, procurement and manufacture of AA Guns had been included in defence spending and Tampella had a production line manufacturing the Bofors 40mm AA gun under license. As you may recall from an earlier Post, the Suomen Hispano-Suiza factory was established in 1936 as a second joint venture with Tampella, with a firm order placed by the Ilmavoimat to buy Hispano-Suiza Cannon for fighter aircraft. Construction of the factory began almost immediately in Spring 1936, with the first Hispano-Suiza HS.404 cannon rolling of the production line in July 1937. The new HS.404 auto-cannon was not only considered the best aircraft cannon of its kind, but on evaluation also turned out to be well-suited to the anti-aircraft role. Factory production was ramped up urgently to fulfill Maavoimat orders, which far exceeded orders from the Ilmavoimat in volume.

Maavoimat HS.404 AA Gun modeled on the German FlaK 30 design (in fact, virtually identical). This was the light AA Gun that equipped almost all Maavoimat Infantry Battalions by the outbreak of the Winter War. Far cheaper than the Bofors 40mm, mobile, relatively easy to transport and with an adequate rate of fire, at the time of the Winter War it was an effective AA Gun. This was the AA Gun that equipped the Light Anti-Aircraft Company attached to “Verenimijä.”

AA Company Headquarters (11 men)

1 x Truck for Company Commander, Driver, Company Sergeant-Major, Clerk, 2 Sigs)

2 x Supply Trucks (2 Drivers)

1 Workshop Truck (Gunsmith, Mechanic, Driver)

3 x Ilmatorjuntapatteri (each Light AA Battery/Platoon, 4 x Truck or Half-Track mounted HS-404 20mm Single-barreled AA Guns, 50 men)

1 x Command Truck (AA Battery CO, NCO, 3 Sigs, Distance Measurer NCO + 1 man)

4 x Trucks, 4 x HS-404 20mm AA-guns (32 men)

1 x Ammunition Truck (NCO, 3 Ammunition Supply men)

2 x Supply Section Trucks (1 Supply NCO, 1 Medical NCO, 2 Cooks, 2 Drivers)

Here, a Maavoimat Ford Truck converted to a Half Track and fitted with an HS.404 single-barreled 20mm AA Gun

Regimental Supply Company (318 men/women)

Regimental Admin Section (10 men)

2 x Office Trucks, 1 Car (CO, NCO, 8 men)

Transport Platoon (113 men)

Company HQ Ryhmä (CO, CSM, 2 Sgts, 4 Sigs/Messengers, 2 x Drivers, 4 man Security Ryhmä)

40 Trucks, 50 Drivers

2 Workshop Trucks, 4 Mechanics

Logistical Supply column moving slowly over a log-corduroy road, Summer 1940: photo reproduced fromhttp://www.kevos4.com with permission

Note that “Verenimijä” was heavily over-allocated transport and logistical support units as the unit was highly mobile and intended to be moved rapidly from spot to spot in order to react to the situation as needed. This was not a standard Regimental Combat Group.

Ammunition Supplies Platoon (43 men)

4 NCO, 1 Sigs, 2 Clerks

2 x Gunsmiths, 2 x Infrared Equipment Specialists, 1 Workshop Truck

16 Men, 16 Drivers, 16 Trucks

Fuel Supply Platoon (22 men)

2 NCOs, 2 Sigs, 2 Clerks

8 Men, 8 Drivers, 8 Trucks

General Supplies Platoon (26 men)

Field Kitchen Platoon (26 men)

Field Hospital Unit (102 men/women – all except Doctors are Lotta Svärd personnel)

Admin (2 NCOs, 2 Clerks, 2 Sigs, 2 Morgue Attendants)

4 medical officers, 4 general surgeons

4 Surgical Assistants, 14 Nurses,

40 Medics

Evacuation Ryhmä: 4 Ambulance Trucks, 4 Drivers, 4 Medics

8 x Backpack and Tent Truck, 8 men

4 x Medical Supplies Truck, 4 men

Field Hospital Kitchen Vehicle, Field Kitchen, 2 man + 4 Cooks

Field Post Office (12 Lotta Svärd)

Clothing Depot (16 Lotta Svärd)

Field Laundry (20 Lotta Svärd personnel)

Maavoimat Field Post Office personnel at work (note the proportion of women in the group) – photo reproduced from http://www.kevos4.com with permission

The Kenttätykistöpataljoona (Artillery Battalion) was added to the Regiment only in late 1938. A two week Combined Arms training exercise for the Regiment in spring 1939 identified a number of problems and some serious weaknesses. The first problem was the low number of trained Fire Observers – and that the Fire Observer Teams did not have night-fighting training at the same level as the Jaeger units they accompanied. By late Summer 1940 this had been corrected, with FO Teams up to establishment and training in night-fighting tactics and the use of night-vision equipment. The second major problem was that despite the Maavoimat’s increasing emphasis on combined arms training through the last half of the 1930’ in particular, the “Verenimijä” Jaeger and Panssari officers while understanding the theory had not had the luxury of working with of artillery support and as a result didn’t quite understand how to use artillery efficiently in support of their units.

Again, this was something that was corrected through some serious training, particularly after Mobilisation. With the issuing of the new Nokia Combat Radios, communications were also radically improved and fire support requests were in practice met very quickly and accurately. Mobility however was good. The Kenttätykistöpataljoona had been issued with the new Sisu license-built Artillery Tractors together with the new 105mm Howitzers and after mobilization, all transport needs were met by mobilized civilian trucks, mostly the Ford Muuli that was in common use throughout Finland. Heavier vehicles were mobilized from the forestry industry and were generally the Sisu trucks of various models.

The third problem was that many of the support and logistical units were not up to strength as manpower priority during early mobilization had gone to ensuring front-line combat units were fully manned. Most “service units were at 40-50% of strength and this was a major concern, one that “Verenimijä” shared with many other units. This in turn was met by assigning a mix of Lotta Svärd personnel who had volunteered for active servive with the Maavoimat together with young males in the 16-17 year old Classes who had been trained within the Cadet Force. These personnel filled two thirds of the supply and logistics slots (including Drivers and horse-handling personnel), supplied some fifty percent of Signals personnel and manned most of the Field Kitchen and Medical positions – a large contribution to bringing the rear-echelon up to the necessary strengths. That even an “elite” unit continually involved in combat such as “Verenimijä” needed to take these steps is indicative of how stretched Finland was to find the necessary numbers of personnel to ensure all units were able to fight effectively. For Finland, this would indeed be “Total War.”

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland