Ukkosvyöry – Tuulispäänä Leningradiin” (Avalanche of Thunder – Whirlwind to Leningrad)

“Whoever said the pen is mightier than the sword obviously never encountered automatic weapons designed by Lahti” – Kenraaliluutnantti Ruben Lagus, Commanding Officer, 21st Panssaridivisoona

Long after the war was over, Eversti Matti Hakkarainen well remembered his first sighting of a Sika, back in early June 1940 when he was a mere vänrikki commanding a Jääkäri joukkue – and a very junior vänrikki at that. “What the hell are those?” he remembered asking. “Those” were a row of large squat truck-sized shapes covered by tarpaulins and lined up neatly down one side of a long shed. Withdrawn from the intermittent fighting on the outskirts of Leningrad two days earlier, the Komppania had been loaded on trucks, suffered an uncomfortable journey back to Viipuri and after a night in an actual bed, had been summoned to stand outside the large warehouse immediately after breakfast. Not that it seemed to be a formal parade or anything, nobody had told them to clean up, or line up or get into formation, just to be there. In fact, nobody had been sure why they were there at all. It had just been the usual Armieja “hurry up and wait.” Only that morning, there had been not too much waiting at all.

The entire Komppania filed into the Shed after the Komppanian vääpeli had opened a side-door and ordered the men inside. They’d all noticed the large tarpaulin-covered shapes lined up along the far side of the shed. A couple of the more curious had begun to drift towards them but a curt command from the Komppanian vääpeli saw them rejoin the rest. The Kapteeni moved up to the front and jumped up onto a workbench. “OK men, Listen Up,” he said. He had no problem being heard. Everyone was listening and wondering what was going on. “We are now a Mechanized Jääkäri Komppania.” He grinned. “And if you want to know what that means, well, for a start, we don’t do so much walking.” He gestured to the Komppanian vääpeli, the Company Sergeant-Major, who in turn gestured to a couple of men he’d deputized to stand next to one of the tarpaulin-covered shapes. “And THIS is what makes us Mechanized.” The tarpaulin was tugged away to reveal a squat armored shape with a sloping front and sides, small windows at the front, four large wheels, a twin 12.7mm with a small shield mounted on the front of what looked to be the passenger compartment and another 12.7mm mounted on each side. “Looks like a Pig to drive,” one of the men next to Hakkarainen had exclaimed, forgetting to keep his voice down. Everyone started to talk. The Komppanian vääpeli’s voice roared. “Keep it down men, keep it down, the Kapteeni is going to fill you in.”

Kapteeni Kaarna waited without expression until quiet returned. “This is the Armiejan’s new Armored Infantry Carrier, it’s called the Sika. We’re the first Komppania to be equipped with them and we’re going to spend the next two days familiarising ourselves with them. The rest of the 21st’s Jääkärit are going to get these over the next few weeks, Company by Company as they arrive. And if you’re wondering Why Us? Well, you all know machineguns back from when we were the old Heavy Machinegun Company, and as you can see, that’s something these Sikas have plenty of. We’ll get familiar with these and then we start training with the tanks and artillery. Now, there’s Instructors from the Experimental Combat Group waiting for us, they’re going to take you over your Sika’s in groups, the Komppanian vääpeli and Platoon Officers will meet with me..” he glanced at his watch .. “at oh nine thirty hours over there. Over to you Komppanian vääpeli.”

“Attention.” The Komppanian vääpeli’s voice snapped the Komppania to attention as the Kapteeni turned and strode off towards the group of uniformed men who’d appeared at the far end of the row of Sika’s. The Komppanian vääpeli gestured to half a dozen Lottas’ who were filing through the door. “The ladies are bringing in Coffee and buns over there, line up and feed your faces while it’s hot. Assemble back here at oh nine hundred. The Instructors will give you a rundown on the Sika’s until midday. Lunch at twelve hundred hours in the Shed here. Assemble at thirteen hundred hours right here for this afternoon’s orders.” He looked around. “Fall out.”

Rather than the next two days, the Komppania spent the next week, twelve hours a day, each and every day, familiarizing themselves inside and out with the Sika – and there was a lot to familiarize themselves with. As their Instructors told them, the Sika had been designed and the prototype built in just three weeks at the Patria plant in Tornio. The basis for the Sika was the standard MSK Truck (Maavoimien Sotilasmalli – “Maavoimat Military Pattern”) chassis and the Cummins I6-170hp diesel engine. The armoured all-welded body was made from 9mm ballistic steel plate from the Tornio Steel Works (although the front armour was actually 14mm) with a raised roof over the driver and drivers assistant seats, a rear door and an open-top troop compartment at the back, which allowed provision for three pivot mounts for single 12.7mm machine guns on the vehicle’s inner side walls – one at the front and one on each side of the troop compartment. A further 7.62mm light machinegun could be fired forward through a gun port by the drivers assistant. The armour itself was sloped at the front and angled on the sides to improve protection.

The internal layout of the Sika itself was compact. The front cab seated a driver and driver’s assistant separated by a gear box cover (both of whom would also be responsible for basic vehicle and engine maintenance). Vision for the driver and assistant was through large bullet-proof glass windows which could be covered by armour-plate visors when in battle conditions. These restricted vision considerably but offered considerable extra protection, albeit often at the cost of smashed fingers (a design flaw, as the Instructors kindly pointed out). A Radio Operator was tucked away in a compact space immediately behind the driver. In the open-topped troop compartment, three machinegunners operated the belt-fed DShK 12.7mm’s, a fourth man was responsible for passing ammunition belts out as needed – a challenging task with three 12.7mm’s and in the confined space available. Last was the Sika Commander for a total of eight men in all. Add to this personal kit, racks for personal weapons, boxes of ammunition (“there’s no such thing as to much ammunition” Sihvonen said in an aside to Salo after Salo had grumbled about how little space there was to stretch out “and it sure beats marching”).

While the Sika had a few faults – for one thing, the Instructors pointed out that the weight of the Armour meant that the chassis was overloaded and as a result, “she could be a real bitch to drive”. But on the other hand “no more walking and enough firepower to blast through the gates of hell” – the combined firepower of even a joukkue of Sikas, let alone an entire Komppania, was devastating when used against enemy infantry and light vehicles caught in the open, and the Sika’s themselves provided real mobility. They had a maximum road speed of 50mph and a range of 300 miles on good roads – and with the 4WD, they had reasonable cross-country capability, albeit with decreased range. The machineguns fitted to the Sikas were Russian DShK 12.7mm’s which had been captured from the Red Army in fairly large numbers in eastern Karelia, the Isthmus and in Murmansk together with enormous stockpiles of ammunition – including AP, AP-incendiary, AP-incendiary and exploding bullets. In hasty trials of captured Russian equipment, they proved to be reliable and effective – and as there were large numbers, hundreds at the least, of them captured, it had been decided to fit them to the Sikas as they came into service. With some work, they had been installed in with a shield for the gunner to provide at least a modicum of protection.

Over the first couple of days, Kapteeni Kaarna worked with the Joukkue Officers and NCO’s and the Instructors from the Experimental Combat Group to reorganize the Komppania around the Sika’s, with 8-man Ryhmät assigned to each Sika. Prior to re-equipping with the Sikas, the Company was a standard Jääkäri Komppania of 141 men organized as follows:

Company Commander (pistol)

Company HQ Ryhmä (Squad)

Messengers (runners)

NCO + 4 men (rifles)

Lookouts/anti chemical weapons Ryhmä (team)

NCO + 3 men (rifles)

Motorcycle messenger (pistol + motorcycle)

Antitank Ryhmä (Squad)

NCO (rifle)

8 men (2 or 4 at-rifles + rifles) (**)

Horse man (horse + cart/sledge), (rifle)

3 Jääkäri Joukkuen (Platoons), in each Jääkäri Joukkue (Platoon):

Luutnantti/Vänrikki (Lieutenant/2nd Lieutenant) (pistol and submachinegun)

Platoon Sergeant (rifle)

Company HQ Squad

2 messengers (runners), (rifles)

4 Jääkäri Ryhmät (Squads), 9 men in each Squad:

Corporal (rifle)

8 men (2 submachinegun + 6 rifles)

Reorganised, the Komppania saw a slight increase in the number of men as follows (6 Sikas per Joukkue allowed for continuous bounding overwatch – alternating movement of coordinated units to allow, if necessary, suppressive fire in support of offensive forward movement or defensive disengagement. As each pair of Sikas takes an overwatch posture, the other pair advances to cover; these two groups continually switch roles as they close with the enemy. The inclusion of 6 Sikas in a Joukkue made it possible to continue to maintain an effective bounding overwatch with sufficient suppressive firepower even when one or even two Sikas were knocked out.

Komppania HQ:

Command Sika: Kapteeni, 1 x Alikersantti (Junior Sergeant, aka Corporal), 6 men

Sika #2: Komppanian vääpeli, 1 x Alikersantti, 6 men

Sika #3: 1 x Alikersantti, 3 men (Armoured Truck Logistical Carrier)

Sika #4: 1 x Alikersantti, 3 men (Armoured Truck Logistical Carrier)

3 Jääkäri Joukkuen, in each Jääkäri Joukkue 48 men as follows:

Command Sika: Luutnantti/Vänrikki, 1 x Alikersantti, 6 men

Sika #2: Kersantti (Sergeant), 1 x Alikersantti, 6 men

Sika #3: 1 x Alikersantti, 7 men

Sika #4: 1 x Alikersantti, 7 men

Sika #5: 1 x Alikersantti, 7 men

Sika #6: 1 x Alikersantti, 7 men

As the men found out, five men in the troop compartment, together with equipment, weapons and ammo, was getting a bit crowded but it worked. Platoon Officer and Sergeants assigned crews and positions, after which the serious training began. Initially, the men assigned as machine gunners trained on the DShK 12.7mm’s, while the assigned driver and drivers assistant learned to drive the Sika’s, first on roads, then trails, then cross-country. As the drivers found out, they did indeed handle like their namesake. Meanwhile, assigned radio operators trained on their new Nokia radios while the vehicle commanders trained on tactics. That was just the first week…. On the second week, the REAL training began……training as a Joukkue and then as a Komppania.

******************************************

Vänrikki Matti Hakkarainen stood with his joukkue as they looked at their Sikas, half smiling at the sight of them. “If we’d had these back in April and May, we’d have been in Leningrad in days,” Salo’s voice behind him muttered. Matti didn’t say so, but he thought Salo was correct. The men were talking quietly among themselves as they waited. The talking faded away as a tall lean officer in the black leather of the Panssari troops jumped up onto a workbench beside the Sika in front of them. Standing on the workbench, Chief Instructor Majuri Järvinen looked around at the 150 odd men of the Jääkärikomppania. Competent looking bunch of lads, he thought to himself with some satisfaction. He knew they’d started out as a Heavy Machinegun company in an Infantry Regiment, converted to infantry and attached to a Jääkäripataljoona, then fought their way down the Isthmus. No shirkers here, they’d seen battle and fought well. Their CO, Kaarna, had put it tersely to him. “Don’t give them any crap about discipline, they’re all aika velikultia, good ‘ol boys the lot of them, their view is they’re in the Army to fight the war and that’s it. Give them barrack depot crap and we’ll never get anywhere with them and you’ll die of frustration. Just tell them what we need to learn and why and show them how to do it, the sensible matters they will sort out and get on with, otherwise they’ll all be like Ellu’s hens.”

Majuri Järvinen nodded, mostly to himself. For the next two minutes, he introduced himself and the other Instructors. Next he talked about why they were forming mechanized Jääkäri companies. “You all know what its like to fight alongside the panzers,” he said, “you went down the Isthmus with them. When they’re with you, they have to slow down so you can stay with them to protect them from the other side’s infantry, when they move at their maximum speed, you can’t keep up. And you know what you men did to the Russian tanks that got separated from their infantry, even when you didn’t have anti-tank guns you managed to take them out.” He singled out Kersantti Hietanen, who’d taken out one of the terrifying Russian KV1 tank’s single-handedly with an anti-tank mine and been awarded a medal for it, with a look and a nod that conveyed an unspoken message of respect. Hietanen stood a little taller as men glanced at him. They knew what he’d done and it had saved their bacon at the time. The memories of that one still gave Hietanen nightmares. After a slight pause, the Majuri continued. “Well, the Sika here is a way to have you men keep up with the tanks – and with a lot more firepower than you’ve had as a Jääkärikomppania.”

“More than we had as a heavy machinegun company,” one of the men spoke up. “We had a lousy dozen machineguns for the whole company.” Majuri Järvinen grinned. It made him look impish, a lot younger than his actual age. “Well, each joukkue now has twenty four machineguns. Eighty machineguns for the entire kompanie, and you men don’t have to carry either them OR the ammunition.” He chuckled now. “And think what it’ll be like for the Russkies, with eighty of these 12.7’s firing at them. They’ll shit themselves.”

“Naaah, they’ll just use more anti-tank guns,” someone grumbled.

“Or artillery,” another grumbler added sourly. “They always use their damned artillery.”

One or two others started to chip in. It had all the sounds of a familiar argument starting up again. The Grumblers vs The Pessimists. Majuri Järvinen winced. Typical Finnish soldiers. Time to get back on topic before the whole thing turned into a grousing match.

“Enough,” the Komppanian Vääpeli’s voice carried. The men settled down without any more noises. Mainly because they were interested in the Sikas and they knew they’d have to listen to find out about them. The Vääpeli had laid it on the line before they started.

“You don’t pay attention and listen to the Instructors, do what they want, you go back to walking. We’re on to a good thing here with these here Sika’s, look at them. We get to ride inside the things, that there armour keeps bullets out, we don’t have to carry nothing.”

“You never did anyhow,” someone commented drily. The Vääpeli ignored the comment. “They carry all the machineguns and ammo and kit for us. It’s a bleeding life of luxury and if any man here screws it up for us, Saatana, I’ll leave it to you men to settle with the culprit.”

It was a long speech for the Vääpeli. He was usually nowhere near as eloquent. There’d been enough growls of agreement and general looks cast around that he knew the point had sunk in and been understood.

With the audience more or less back in hand, Majuri Järvinen recommenced. In broad terms, he enthusiastically outlined the training schedule that would occupy the next two weeks. And then, even more enthusiastically, he talked about the Sikas. “Armour on the side is 9mm’s of ballistic steel, angled to increase protection. That 9mm will keep out rifle bullets and shrapnel from grenades and most mortar shells. It’ll keep out machinegun bullets except at really close range. It won’t stop close-in artillery and it sure as hell won’t stop an anti-tank round. The front armour is 14mm. That WILL stop even a heavy machinegun bullet and it’s angled acutely, so at long range it MAY stop a light anti-tank round, no promises, but its good stuff, the best that the Tornio works can make. The glass windows are armoured glass but they ARE a weak point. When the shit hits the fan, get the steel hatch covers down over the glass and use the viewing ports. Your gunners are your protection and your commander tells you where to go, what to do. Your protection is your firepower, speed and coordination with the rest of your joukkue, NOT your armour.”

“Also, you see these tubes on the front here. These are for firing smoke grenades. You can lay your own smokescreen in a few seconds and then fall back behind it. BUT it does hide the enemy from you as well as hide you from the enemy. Needs to be used effectively. What else? The engine is a diesel, and diesel is a lot harder to set on fire than petrol, so if you are hit you won’t be deep fried instantly, you’ll likely have time to get out if you’ve lived through the hit. Lots of guns, lots of bins for ammo, although you will have to be careful not to run out, these guns can use it up real fast. Personal weapons – there’s racks inside to fasten them to when you’re moving. Suomi’s and Rumpali’s are recommended, the SLR’s tend to get caught up when you mount and dismount in a hurry. Kit? Well, you can stuff all your kit in the bins under the seats….”

“Now the machineguns, the Russian 12.7 is a good heavy machinegun for all that it’s Russian. Reliable, tough, good range, 600 rounds per minute. It can take out light vehicles. No good against tanks, but you’ll be working with tanks and anti-tank gun units, your basic tactic is of you come up against tanks, you fall back and draw them on to our own anti-tank guns and let them take care of the business. We’ve got plenty of ammunition for the 12.7’s that we captured from the Russians, that hard part is getting it up to you so make sure you don’t go wasting it. Joukkue officers, you need to keep track of how much ammo is used and order resupplies. Every Joukkue is going to get a couple of armoured trucks for carrying ammo and a bit of reserve fuel but that’s for combat resupply, you still need to make sure you stay on top of your current ammo and fuel supply….”

“…..Now, you all know what its like fighting on the Isthmus and in Karelia. One of the big advantages of the Sika is that it’s small and fast. And the four wheel drive means you can go pretty much anywhere the ground is firm. Unlike a tank, you CANNOT drive through ditches. Getting stuck in a swamp will get you killed and swampy ground is just as bad…..”

“Now, fighting in the forest. The Sika is OK in forested terrain as long as it’s not too rocky or swampy. You have to always keep your eyes wide open, the Russians, they’re mostly scared of the forest but they can hide in it too. You all know what the Russians are like when they dig in, there snipers are good, they can hide anti-tank guns as well as we can so you have to really look. Going down roads, you have to be careful – those curves and corners, a Russian tank or an ambush can be anywhere. BUT the Russians are also cautious, yhey didn’t like to advance their tanks without close infantry support and with no infantry, those Russian tank crews often abandon their tanks totally intact for us to capture and reuse. So we use that to our advantage.”

“The Forest is our friend as well as our enemy, it hides us as better than it hides the Russians and we can move through it to outflank them and attack them from the rear. The Russians hate it when we do that.” He grinned. “Remember that to them. Karelia is an alien land and they’re scared of the forest and of us. And the Sika coming out of the forest where they don’t expect it will scare the living shit out of them more often as not. BUT you have to know the Sika’s limitations, which we WILL show you, the last thing you guys want is to be screwed by the Russians because you got your Sika bogged down or broke it doing something it’s not designed to do…… “

“…..As a Mechanised Jääkärikomppania, more often than not you’ll have additional platoons or sections attached based on the mission. Armoured Cars, mostly the new Kettu’s that are coming in, we have some Sika’s with the 81mm mortars for direct fire support, also there will be a few half-tracks available with the rocket launchers, also some flamethrower half-tracks and the anti-tank guns. You’re going to learn to operate with them, the anti-tank guns especially, if you run into Russian tanks, your job is going to be to lure them back onto the anti-tank guns and let the AT boys shoot the shit out of them while you take care of any Russian infantry with them….”

And so it went on…..

******************************************

Change gears. Reverse up. Change gear again, hammering the gear lever that always seemed to stick when you wanted to go from reverse to first. Turn left using brute force on the steering wheel as the Sika commander yelled directions into the intercom. In the other seat, the assistant-driver was cursing as he looked out for obstacles and yelled directions. The Sika bucked and jerked as the engine picked up power. The seat restraint belts bit painfully as the Sika bounced through a slight dip in the ground. Avoid that tree. Move into the firing position ahead. Above, the barking roar of the 12.7’s as they opened up. Change into reverse right away and hold the clutch down, ready to move. Make sure you know where to back up without running in to anything too large. A tree waving when you hit it will give your position away. Reverse up fast. Jerk as the Sika whacked a tree that was too large and solid to give much. Shit! Change into first. Quick. Quick. Go left. Move into the next firing position. Wait. This time, forward now, over the ridgeline and weaving down through the trees. Someone else, another Sika, close by, moving in parallel. Into the next firing position.

The 12.7’s roared again, covering fire as the second section moved up and through. Bounding overwatch, they’d learned to call it. Covering each other with fire as they moved. Time to move again. Reverse. Go right this time. Accelerate. Incoming fire. The Sika commander yelling instructions to the gunners. All four 12.7mms firing. Reverse. Left into the next position. Left again. More firing. The joukkue CO on the net now, calm, very controlled, calling directions and orders. Reverse. Move right. Back in the troop compartment a frenzy of reloading, belts being passed up, instructions yelled. The Sig in the seat behind talking on the radio. Move again. Keep moving forward through the forest, weaving through the trees. Guns firing. Glimpse of the other Sikas to left and right. Go hull down and wait.

A sudden burst of firing from above. “Got them.”

“Driver. Move out.”

Reverse out. Forward. Left. Left. Right. Red smoke suddenly fills the inside of the Sika. Choking, Lehto bails out straight over the top of the Sig, gasping for air, eyes tearing up. The smoke from the simulated hit is acrid and thick. The others, in the troop compartment, have already gone over the sides. The Sig and the co-driver are the last out, choking and swearing. The Instructor has already started in on them, his face red with anger, pounding a fist on the side of the Sika. “Left. Left. Right. Every bloody time Left Left Right. Every time you do the same thing. You think the Russians are morons, that they won’t notice something as simple as Left Left Right Left Left Right. You are all now officially bleeding dead. Fried. Crispy Critters. You understand that? You want to be deep fried. No? Then change. Alternate. Vary. Do it different. Never the same. Understand? Yes? Right. Back in and lets do it again!”

Back in the Sika, Hietanen gets on the intercom. “OK, my fault. I screwed up. It’s my job to tell you which way to go.” Lehto cut in. “Right. Why not toss a coin.”

“Yeah yeah yeah. Driver. Move out.”

Reverse out. Change into first, jerk ahead to the right.

“Target. Two o’clock.”

Guns firing. “Move forward. Fast. Fast. Stop. Target 10 o’clock.”

And again. And again. And again, until at the end of the day they were bone-weary with exhaustion. After which they got to service the Sika, clean the guns, replenish the ammo bins. And then in whatever time was left they got to eat and then sleep.

The targets were popups, the rounds were real. Live firing, individual vehicles to start with, then in Sections, then Joukkueet, then the entire Komppania. Intensive live firing. First at silhouettes, then as they improved, at moving targets. Firing on the move was harder still. Practicing mounting and dismounting into action on foot. “A Sika can’t clear trenches, only infantry can do that.”

Working with the tanks, coordinating the Sikas and the tanks in movements into battle, in combat itself and in withdrawals. Radio procedures. Command and control. Replenishment. Maintenance. Working with tanks, anti-tank guns, artillery and infantry on foot. Time was short and there were never enough hours in the day. They trained twelve, fourteen hours a day. The men grumbled and complained, but very few tried to get out of it. Those that did, Hakkarainen or Kersantti Hietanen simply told them if they didn’t like it he could have them transferred back to one of the infantry battalions that did it the old way, nobody was begging them to stay if they didn’t want to be there.

Well into their second week of training, Hakkarainen decided he need a bit more time getting familiar with the 12.7mm’s. When he walked into the Shed after dinner, it was to find Sihvonen, Salo and Linna there with two of the Instructors, the front 12.7mm dismounted and one of the Instructors at work with a welding torch. On the workbench next to “his” Sika were a couple of Lahti 20mm AA cannon. Hakkarainen looked at Sihvonen, Salo and Linna and raised an enquiring eyebrow. Sihvonen looked at Salo. They both looked at Linna, then all three of them looked back at Matti. The instructors didn’t even look up from their metalworking. “Well, it’s like this Sir, my younger brother, he’s in the Ilmavoimat at the air base just down the road, he’s an Armourer and he told me they had a warehouse full of those new Lahti AA guns for putting on trucks and things as AA guns for airfield defence, but they got no trucks to put them on, so we did a deal. We figured those Lahti 20mm’s, they pack a hell of a punch, they can take out a tank and we figured if we put two of them on the front, we could take out anything we see, and make the other two 12.7’s twins instead of singles.” Sihvonen was getting more and more enthusiastic as he talked.

Hakkarainen looked at the Lahti’s, thought about what it would be like to be on the receiving end of 20mm AP cannon shells arriving at 360 rounds per minute – from each barrel. From every Sika in his joukkue. After a couple of seconds, he grinned. “How soon do you think you can have it ready?” he asked. One of the instructors looked up. “Be ready by morning,” he said. Hakkarainen thought about it. “I think I’ll just leave you to it,” he said. “And Sihvonen, Salo, Linna, if anybody asks what’s going on, I authorized whatever you’re doing.” By the next morning, the single 12.7mm on the front had disappeared and a pair of 20mm belt-fed Lahti cannon had taken their place. And instead of a single 12.7mm mounted on each side, there were now two twin 12.7mm machineguns mounted. It looked rough and ready, and things like the belt feeds for the 12.7mm’s were a real kluge, but it seemed to work, certainly the pivot mounts tracked smoothly and the reinforcing seemed strong enough to take the recoil when the guns were fired. Sihvonen, Salo and Linna on the other hand looked a bit bleary-eyed. A canteen of hot coffee perked them up.

As they prepared for the days exercise – a company movement forward and into the attack – the Kapteeni wandered over. “Some changes to your Sika, Vänrikki?”

“Yes Sir,” Hakkarainen acknowledged. “We fitted a pair of Lahti 20mm’s on the front mount and converted the 12.7’s to twins.”

“Hmmmmm,” Kapteeni Kaarna climbed into the Sika and took a thorough look. Hakkarainen followed him in. “And this happened when, Vänrikki?” “Ahhh, last night Sir.” Kaarna shook his head. “I’m not even going to ask where you got those 20mm’s from.” He looked at the twin Lahti 20mm guns thoughtfully, then somewhat quizzically at Hakkarainen, then at the guns again. “Let’s take them out to the gunnery range after the exercise and see what they can do.”

The exercise was not routine. No exercise with these instructors ever was. Two of Hakkarainen’s Sikas got stuck and had to be towed out. Under fire. Two were destroyed by simulated enemy fire. They got lost. They let enemy infantry get too close. They screwed up on the radio procedures. “Saatana,” Kersantti Hiekanen complained into the joukkue radio net as red smoke from a simulated hit billowed out from a third Sika and the men bailed out, choking and swearing, “Ei meist’ o’ mihkä!”.” They could all see an Instructor, dressed in bright orange for visibility, storming towards the hit Sika, obviously preparing to rip the crew new assholes. Hakkarainen shuddered. He knew his turn for public humiliation would soon be coming.

In the event, he was spared the public humiliation. He received that privately. If you could call the back of his Sika, with the Kapteeni and one of the Instructors and the rest of the Sika crew en route to the gunnery range private. “That Instructor certainly has an excellent command of the Finnish vernacular,” Linna said admiringly to Sihvonen as he pulled his diary out in the barracks later that evening to jot down a few notes. “For your novel, is it?” Sihvonen asked somewhat sarcastically. Linna grinned. “You want to be in it Sihvonen?” Sihvonen laughed. “If we all live through this, I won’t give a shit whether I’m in it or not, I’ll just be happy I survived.”

On the gunnery range, they’d stopped in a prepared firing position. “Lets see what it does,” Kapteeni Kaarna said mildly. Hakkarainen nodded to Linna, who promptly opened up. The Lahti’s had been loaded with belts of mixed AP and AP-Tracer. A line of fire walked down the static targets as the twin 20mms roared, cascading empty shells onto the floor of the Sika.

“Perkele,” Linna said, his voice hushed, almost inaudible under the roar of the twin Lahti’s.

The rest of the crew, Hakkarainen, Kapteeni Kaarna and the Instructor watched in awe as the targets disintegrated in a maelstrom of 20mm cannon shells, splinters and dust. “Saatanan mahtavaa” Linna screamed at the top of his voice as he hosed the targets down. Hakkarainen looked sideways at Kapteeni Kaarna. The expression on his face hadn’t changed. Linna ceased firing when the belts ran out.

“You know,” the Instructor said thoughtfully, “there’s an old T-26 in the back of the shed, too damaged to use and most of the useful bits have been stripped off. Why don’t we have it dragged out here and we’ll test the guns on that.”

Kapteeni Kaarna thought about it. Then he smiled. “Let’s do it.”

It was midnight before Hakkarainen and his men got back to the barracks. After they’d shredded the T-26 on the range, rather conclusively showing what the Lahti’s could do to a Russian tank in the process, they’d still had to clean down the Sika, strip and clean the guns, collect all the cartridge cases, refuel and service the Sika and get it set up for the next day’s exercise. Kapteen Kaarna and the Instructor had left, engrossed in a discussion of the guns. Hakkarainen had stayed and worked on the Sika with his men. And he’d made sure that they got a hot meal from the kitchen. He’d had to coax the grumbling old Lotta on night duty to get her into motion, but she’d rustled up something for them in the end.

******************************************

The next day’s exercise was another bitch. By the end of a day that was straight from hell, Hakkarainen was seriously considered applying for a transfer to a position as a weather monitor on the Kola Peninsula. Kapteeni Kaarna beckoned him aside as they began cleaning up the Sika’s outside the shed. The sinking feeling in his stomach disappeared as Kaarna asked him where the Lahti’s had come from. Hakkarainen did his best to diplomatically state that they had been “acquired” from the Ilmavoimat, in the best traditions of armiejan scrounging. “Dammit Hakkarainen, just tell me who it was that got them,” Kaarna finally exploded. “I want to know if we can get more of the damn things.”

“Oh.” Hakkarainen deflated. “Sihvonen got them, his brother’s an armourer in the Ilmavoimat, ththey’veot a warehouse of them down the road and they did some sort of a deal.”

“Thankyou so very kindly Vänrikki Hakkarainen.” Kaarna still sounded exasperated. “Perhaps you would be so good as to summon Sihvonen to join us.”

Hakkarainen did. Sihvonen came over, snapped to attention. Even, wonder of wonders, saluted. “Cut the crap Sihvonen, we’re not in the field, there’s no enemy snipers around,” Kaarna’s mouth half-twitched into what might have been a smile. “Now, do you think your brother could lay hands on a few more of those Lahti’s, say a pair for every Sika we’ve got? Plus ammo for training?”

Sihvonen forgot military appearances instantly, wrinkling his forehead, removing his cap and scratching his head. “Have to talk to him Sir, its easy enough to explain a couple going missing, but forty of them, that might be a bit much to ask.”

“Well, you can take the evening off, take Linna and Salo with you and have a chat with your brother, I’m going to talk to our Majuri Järvinen and see if there’s anything he can do for us.”

As it turned out, Majuri Järvinen went up through his own line of command. His request for forty Lahti 20mm’s was expeditiously declined. Conversely, his request for large amounts of 20mm ammunition for training purposes was approved almost immediately. Sihvonen in turn advised that his brother could not see his way to “losing” that many Lahti’s, but certainly the small bunker that they had been moved to was somewhat isolated and not guarded. Thus it was that two nights later, a surprise Soviet air raid took the airbase by surprise. Over a period of an hour or so, a number of sporadic explosions wracked the airbase, none of them doing any appreciable damage – with the single exception of an isolated bunker that was being used to store a number of Lahti 20mm AA guns. A Soviet bomb had blown the whole bunker to fragments, leaving nothing but an overly large hole in the ground and some fragments of wood and metal. The base Armourer, one Sihvonen, reported the writeoff of some forty Lahti 20mm AA guns and put in the paperwork for replacements.

A couple of hours after the Soviet air raid ended, Sihvonen, Salo, Linna and half a dozen other men from Hakkarainen’s joukkue drove into the army base in four rather heavily laden old Ford Muuli trucks, the springs groaning under the weight of their loads. Strangely enough, the Komppanian vääpeli was at the Gate when they arrived and waved the trucks through himself without a security check. The Kersantti of the Guard, who strangely enough was also from Kapteeni Kaarna’s Komppania, blinked not once as the four trucks groaned and squeaked past. Indeed, he even waved at Sihvonen as he leaned nonchalantly on the sill of the passenger’s window. The trucks disappeared towards the Shed that was home to the Sika’s and very shortly afterwards, the sounds of a large group of soldiers hard at work could be heard.

Over the next few days, the Sikas rotated through the shed, three or four at a time. Each morning a few more would emerge with the modifications completed. It took more than a week before the last one was done. And then, on the gunnery range, with the entire Komppania lined up in their Sikas, the sheer firepower of twenty twin-Lahti 20mm cannon and forty twin-12.7mm heavy machineguns was tried out ….

“Impressive,” Kapteeni Kaarna stated blandly.

“Mahtavaa” one Sotamie Maatta was heard to say as he watched chunks flying off the old Russian T-26, which was now looking more like Swiss Cheese than a tank. “Impressive” was something of an understatement. Even the Instructors from the Combined Arms Experimental Combat Group stood there with their jaws hanging, a look of stunned amazement on their faces. Marjuri Järvinen was frantically making notes.

After the day’s live shoot on the gunnery range ended, Kaarna summoned Hakkarainen to his temporary office. “And bring Sihvonen, Salo and Linna with you Vänrikki,” he added, almost as if it was an afterthought. What followed there arrival was not what you would call a speech, but the Kapteeni made it plain to Sihvonen, Salo and Linna that was he well pleased with the initiative they had shown. “Quite impressive Korporaali Sihvonen, Korpraali Salo, Korpraali Linna,” the Kapteeni said blandly, grinning at the surprised look on their faces. “Congratulations on your promotions.” He handed each of them the shoulder stripes for their combat uniforms. “I expect to see you wearing these by the morning.” He turned to Hakkarainen. “And lest I forget Luutnantti, these are for you.” He handed Hakkarainen a set of collar tabs for a 1st Lieutenant. Then shook his hand. “Good work Luutnantti.”

Another week of training followed. Orders came to be prepared to move out the next day. Kapteeni Kaarna gathered the company together outside the Shed to announce their eminent departure. To Vänrikki Koskela, of the Third Joukkue, he had delegated the task of issuing instructions to the Komppania. In his opinion, Koskela, who was taciturn & overly self-conscious, needed all the command experience he could get. Koskela stood in front of the Komppania, looking as though he was meditating how to begin. He always had difficulty giving orders and he would have far preferred Kapteeni Kaarna to issue them. “Er … we move out at 6am tomorrow morning with our Sika’s. …. You NCO’s ….. it’s up to you to look after things. See that all extra equipment is handed in. Make sure you have a change of underwear and socks and your greatcoats and blanket in your packs. And of course bring your weapons and body armour and helmet. Anyone who needs replacement kit, see the Quartermaster. Sika commanders, make sure your Sika’s get all their maintenance done today, all fuel to be topped up, a full combat load of ammo for the Sika’s as well as your personal weapons. Be as quick as you can.”

Kersantti Hietanen ventured a question. “Where are we going? Way the hell out in the wilderness I suppose?” Koskela’s glance first sought out Kapteeni Kaarna, who stood looking blankly inscrutable, then sought the horizon as he answered. “I can’t tell you. All I know is the orders. Get going now, and don’t waste time”. That was all the men learnt. Indeed it was all anyone except Kaarna knew, yet everyone was eager to be off. The rest of the Armieja was fighting, not training, and while no-one was eager to go back to the war, the sooner the war was won, the sooner everyone could go home again. Such was their eagerness that men even asked the NCO’s what else they could do, a rare occurrence in any army. With Luutnantti Hakkarainen off with the Kapteeni, Kersantti Hietanen took charge of the Joukkue. His booming voice rose above the din as he directed the preparations, first in the barracks and then as they worked on the Sika’s. Hietanen was a powerfully built and cheerful young man who had established his authority over the joukkue chiefly due to his immense strength.

They gossiped as they worked, but nobody knew more than anyone else where they were going. One of the men from Lammio’s joukkue came running over. “The panzers are moving out.” They abandoned their tasks for the moment to step out of the shed and watch. The panzers were indeed moving out, long columns of them on their transporters, followed by the seemingly endless logistical tail. It seemed that the entire Divisoona was indeed moving. Ordered back to their tasks, all day they worked on the Sikas. Maintenance. Engines. Oil and grease, topping up everything that could be topped up, servicing everything that could be serviced. Clean the guns. Fill the ammunition belts and the ammo lockers. Check personal weapons, check their individual Lohikäärme Vuota, the body armour that had proved so valuable in battle on the Isthmus, sharpen puukko knives, the now standard-issue Isotalo-Taisteluveitsi (“Isotalo fighting knives”) and the almost two-foot long combat machetes that could be used to chop down a tree or take a man’s head off, load up on extra food – you could always fit in something extra inside the Sika. Extra kit tied on the outside – cammo nets, tarpaulins, spare tires, chains and rope for towing, planks for getting out of the mud if they got stuck, axes, saws, spare parts, whatever seemed necessary, whatever could be scrounged. When they moved out the next morning, Rahtainen’s Sika had a live pig in a hastily made cage tied on the back. Kapteeni Kaarna looked at it expressionlessly as it passed by, squealing loudly. Luutnantti Lammio looked shocked as he stood in his command Sika watching Hakkarainen’s joukkue drive past him.

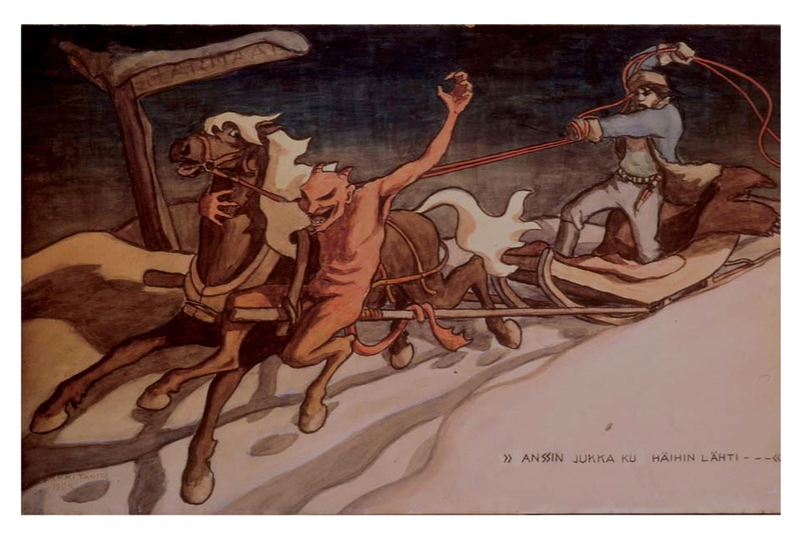

Hakkarainen grinned at Lammio from his command Sika, which his men had named Anssin Jukka, after the notorious Ostrobothnian knife fighter of the same name. Behind him, Salo started singing. The rest of the crew joined in first, roaring out the words, then the rest of Hakkarainen’s joukkue joining in, as much to shock the rather prim and proper Luutnantti Lammio as for any other reason. Also, much to Hakkarainen’s embarrassment, his men seemed to have altered the words somewhat….

“When Luutnantti Hakkarainen set out for the war

the Devil sat down on the shaft

like a gust of wind drove Anssin Jukka

past the Pikku-Lammio Sika…”

Hakkarainen wasn’t quite sure what that said about him or his men, given the rather grim melody of the song, which told of “The Horrible Wedding in Härmä, with drinking and fighting going on — from the hallway to the head of the stairs dead bodies were carried…” In a way, Hakkarainen thought, the singing of the song rather typified the joukkue’s spirit of aggressive intent – though whether it was towards the Russians or towards Luutnantti Lammio was perhaps the question to ask. As if to illustrate the song rather more graphically, Salo flipped his Isotalo fighting knife in the air and caught the blade in his fingers, raising it to his forehead in an ironic salute to Luutnantti Lammio as they drove past. Behind Lammio, his men were grinning. Hakkarainen thought perhaps he should rebuke Salo, but then he gave a mental shrug. As long as the men followed his orders, a certain amount of leeway was permissible. With a grin, he turned his face to the road, caught up in the grim elation of the moment as they headed off towards battle once again……

And just as a bit of an informational post-script….

In the mid-1800s in western Finland, in a region called Ostro-Bothnia along the Gulf of Bothnia, there was a tradition similar to that of the “gun-slingers” of the old American Wild West. Only these guys, mostly wealthy and strong farmers, used the Finnish puukko-knives instead of six-shooter colts to settle their disputes – so perhaos one could call them knife-slingers. They liked fast horses but did not ride them. Instead they had the horse draw a two-wheel cart with iron wheels. They liked to gallop through the villages and enjoyed the drumming of horse hoofs and the rattling of the wheels on the gravel roads. In this they were like some present day Finns in their cars…

Now these guys were very proud of themselves and wanted to be kings of the hill. They used to crash parties like weddings and do all sorts of mischief, fighting against others and against their own gang members. The result was of course a high murder statistic. Some of the most famous of these knife-fighters (and they WERE famous within Finland) were Isontalon Antti, Rannanjärvi, Pikku-Lammi and Hanssin Jukka (more often spelled Anssin Jukka, Anssi being the family name and Jukka “John” the first name, so Anssin Jukka translates to Jukka of Anssi). The memory of these knife-fighters still lives in a very popular song about a wedding at a village called Härmä in 1868 and it can still be bought in many versions, recorded by many military bands. The words go about like this:

“There was a terrible wedding at Härmä

with plenty of drinking and fighting.

Blood was carried there in a damn big pile.

When Anssin Jukka went to the wedding

the devil sat on the shaft of his cart.

Like a gust of wind he galloped past Pikku-Lammi on the way”.

Anssin Jukka arrived at the wedding and shouted from the door: “Good evening, are you not going to show me the beautiful Tilda of Alitalo?” Alitalo was the name of the farm, Tilda being the bride. The song continues, telling that people were playing and dancing till Anssin Jukka came – and then the fight started at once. By the time the fighting ended, there were so many corpses that the row of them reached from the vestibule down to the porch stairs. On the way to the wedding, Anssin Jukka had insulted Pikku-Lammi by galloping past him. This, of course was an insult so they got into a fight at the wedding and ….

“Anssin Jukka had a knife

and Pikku-Lammi had a stake.

There on the floor heaven opened

for Pikku-Lammi as Anssin Jukka cut his throat”.

The song ends by wondering whether the authorities rest well knowing that “the best of the boys has spent ten years in the prison of Vaasa.” Anssin Jukka was a bit of a hero – for instance in the 1930s the glider club at Vaasa had their Grunay Baby glider was named after Anssin Jukka. Also, Marshal Mannerheim’s personal transport aircraft, a DC2, was named “Hanssin Jukka” – one can in all honesty say that very few Military commanders of any nation have had their personal aircraft named after a knife-fighter. This in itself should perhaps have been a warning to the Russians not to attack Finland and probably the popularity of “Anssin Jukka” reflects some deep characteristic of the Finnish soul, who knows….. Anyway, everybody knows about Hanssin Jukka, a Finnish knife-fighter of the 1800s…

Here’s the Finnish and English lyrics for Anssin Jukka Ja Härman Häät. There’s quite a few versions of this, this is only one…..

Härmässä häät oli kauhiat / There was a terrible wedding in Härmä,

siellä juotihin ja tapeltihin. / there was drinking and fighting.

Porstuasta porraspäähän / From the porch to the end of stairway

rumihia kannettihin. / corpses were carried.

Anssin Jukka se häihin lähti / Anssin Jukka went to wedding

ja valjasti hevoosensa. / and harnessed his horse.

Eikä hän muita mukahansa ottanut / He didn’t take with him others

kun Amalia-sisarensa. / than his sister Amalia.

Anssin Jukka kun häihin lähti, / When Anssin Jukka went to wedding,

niin aisalle istuu piru. / devil sits on shaft.

tuulispäänä ajoo Anssin Jukka / Like a gust drove Anssin Jukka

Pikku-Lammin sivu. / past Pikku-Lammi.

Mikähän silloon sen Anssin Jukan / What might then Anssin Jukka

mieles olla mahtoo, / have in his mind,

kun se tuota rytkypolkkaa / when he that rough polka

soittamahan tahtoo. / wanted to play.

Pienet poijan perhanat / Little damn boys

sen tappelun aloottivat, / started the fight,

kaksi oli Anssin veljestä, / two were Anssi brothers,

jokka tappelun lopettivat. / who ended the fight.

Rytkypolkkaa kun soitettiihin, / When rough polka was played,

niin poijat ne retkutteli. / boys were wrestling.

Hiljallensa se Anssin Jukka / Silently Anssin Jukka

helapäätä heilutteli. / wagged a knife.

Anssin Jukka se heilutteli / Anssin Jukka shaked

tuota norjaa ruumistansa. / his flexible body.

Kehuu Pohjan Kauhavalta / Bragged from Ostrobothnian Kauhava

sankari olevansa. / the hero to come from.

Anssin Jukalla puukkoo oli / Anssin Jukka had a knife

ja värjärin sällillä airas. / and dyer’s jack a shaft.

Alataloon laattialla / On the floor of Alatalo

aukes Pikku-lammille taivas. / the heaven opened to Pikku-Lammi.

Herran Köpi se puustellin portilla / Master Köpi at the gate of farmhouse

rukooli hartahasti. / prayed earnestly.

Anssin Jukka se puukoolla löi / Anssin Jukka hit with his knife

niin taitamattomasti. / so unskillfully. (you slit with a knife, don’t stab or you kill somebody)

Anssin Jukan puukkoon se painoo / The knife of Anssin Jukka weighted

puolitoista naulaa. / a pound and a half.

Sillä se sitten kutkutteli / With it he then tickled

tuota Pikku-Lammin kaulaa. / neck of Pikku-Lammi.

Anssin Jukan puukoonterä / Blade of Anssin Jukka’s knife

oli korttelia ja tuumaa; / was a span and an inch;

sillä se sitten koitteli, / with it he then tried,

jotta oliko se veri kuumaa. / if blood was hot.

Anssin Jukan puukoonterä / Blade of Anssin Jukka’s knife

oli valuteräksestä; / was of cast steel;

sillä se veren valutti / with it he drained the blood

tuon Pikku-Lammin syrämmestä. / from Pikku-Lammi’s heart.

Mitähän se harakkakin merkitti, / What did the magpie mean

kun saunan katolle lenti. / when it flew on the roof of sauna.

Vihiille piti mentämän, / It was to be a wedding,

vaan rumihia tehtiin ensin. / but corpses were made first.

Kahreksan kertaa minuutis / Eight times in a minute

tuo rivollipyssy laukes. / the revolver went off.

Alataloon laatialla / On the floor of Alatalo

Pikku-Lammin kurkkuk aukes. / throat of Pikku-Lammi was opened.

alataloon häis kun konjakki loppuu, / When brandy run out at Alatalo wedding,

niin ryypättihin viinaa. / we drank spirits.

Niinimatosta Pikku-Lammille / Of a bast carpet for Pikku-Lammi

tehtihin käärinliina. / a shroud was made

Ja voi kukn se yö oli kauhia / Oh how that night was terrible

kun juotihin ja tapeltihin, / when it was drunk and fought,

ja pirunmoosella lehmänkiululla / and with a large cow pail

verta vaan kannettihin. / blood was carried.

Eikä se Anssin Jukka olisi tullu / Anssin Jukka would not have become

rautojen kantajaksi, / a carrier of shackles

jos ei menny alataloon häihin / if he had not went to Alatalo wedding

konjakin antajaksi. / as a server of brandy.

Jokohan ne herrat Kauhavalla / Wonder if masters at Kauhava

on hyvän levon saaneet, / have already got a good rest,

kun kymmenen vuotta parhaat poijat / when for ten years the best boys

on Vaasan linnas maanneet? / have lied in the prison of Vaasa?

Artist Erkki Tanttu has made a famous painting of this instance leading to that Horrible Wedding, masterfully depicting the Finnish spirit of aggressive intent, see below. So when Hakkarainen, Hietanen, and the rest of the Finnish Army went on the offensive in August 194o, perhaps there was the Devil sitting on the roof of their Sika…

They drove all day in convoy, following the road north of Lake Laatoka and then turned south. “It’s the Svir then,” Kersantti Lehto muttered from his Sika. The entire armiejan seemed to be in motion, not just the 21st, but other divisions mixed in, everyone rumbling south towards the Svir – armour, artillery, infantry, pioneeri, soldiers of every branch imaginable, all with their orders, all looking grim and unsmiling. They knew what was coming and not many were looking forward to it. There were a few who were and Lehto was one of those. He was singing quietly to himself as his Sika rumbled along. His front gunner, Kaukonen, looked sideways at him. “Sounds like you’re enjoying this,” he grumbled. Lehto looked at him and grinned. The grin never touched his eyes, which were an icy blue. “Killing Russians makes me happy,” he said. “And with this baby,” he patted Kaukonen’s twin Lahti’s, “I can be sure I’m going to be very happy indeed.”

In his command Sika, Hakkarainen was studying the map. “Almost there,” he muttered to himself. Twenty kilometres to the Svir. Already the sound of the artillery was a constant, if distant, rumble that was audible even over the diesel engines and the road noise. The Kapteeni had been clear about the movement orders, but aside from the assembly point south of the Svir, he knew as little as Hakkarainen about what they were to do after that. Battalion HQ came up on the radio net. Riitaoja, who Hakkarainen had moved to his Command Sika as the Sig, piped up, “Message from Battalion Sir.” He flicked a switch to relay the radio signal over the internal intercom so everyone could hear.

“Possible Russian infiltrators anywhere between here and the Svir,” the Battalion HQ Sig’s voice was clear. “Entire Battalion on Alert posture. HQ out.”

The Radio net came alive with chatter, Komppania and Joukkue both. Hakkarainen ordered his joukkue to full readiness, guns cocked and ready. They rumbled on, the men now scanning the forest and the intermittent fields they passed by.

Hakkarainen did a quick positional check. His Sika’s were all maintaining standard close-up convoy distances, Lahti’s angled alternately to left and right. Alikersantti Virtanen’s Sika was in the lead, followed by Hakkarainen’s, then Lehto’s, Hietanen’s, Lahtinen’s and lastly Rokka’s. Ahead of them was Koskela’s joukkue and the Komppania HQ Sika’s, behind, bringing up the rear, was Lammio’s joukkue. Apparantly there were remnant Red Army units on the Finnish side of the Svir, Red units that had survived the Finnish counter-offensive and were continuing to fight behind the Finnish lines. Not to much effort had as yet been put into mopping them up, the main focus was on the new fighting south of the Svir and the destruction of the Red Army units on the front. These stragglers had been left for later, but they could still prove a nuisance. Which, indeed, turned out to be the case just a few kilometres down the road. A checkpoint. A truck further ahead, half of the road, burning sullenly. Shooting. Rifles and machineguns. Russian and Finnish. A thin line of Finnish soldiers burrowed into the ground, facing south, older men, their faces grim. An NCO came running over to Kaarna’s command Sika. “Sir, there’s Russian’s up ahead, don’t know where they came from, they ambushed our trucks, there’s fighting up ahead.”

Kaarna leaned over. “Any idea how many Russians?”

“No sir, my men and I, we were in the last truck. Some of the others from up there joined us, there’s fighting up there, we was just about to advance down the road.”

Kaarna thought for a moment. The Sig could get Battalion HQ, which was behind them with Two Company, commanded by young Autio. He advised Battalion of his intentions. Majuri Sarastie concurred. He looked down at the old NCO. “You and your men stay here, I’ll send anyone we recover back to join you. When you have enough, send a group up to recover the trucks.” He got on the radio, issued commands to the joukkue commanders. The Komppania fanned out either side of the road, forming an extended line, Hakkarainen’s joukkue on the left, Lammio’s on the right, Koskela’s on either side of the road and the HQ section as reserve. Virtanen was first to spot their own men from his command position in the lead Sika. Sweaty men bolted towards then, running with their last strength, looking backwards over their shoulders.

“Something’s scared the rabbits.”

“Not “Something”, it’s the enemy. Just be alert on the guns!”

“Shit! The enemy can’t have penetrated this far behind our lines.”

“Well, I doubt they’re running from the Germans.”

Hakkarainen leaned over the side. “You, where’s the enemy, what strength?”

Ignoring him, the men ran by, heads down, panting. At least all of them so far still had their weapons. An NCO, an old, greying, overweight Kersantti, stumbled towards them. Hakkarainen leapt straight over the side of the Sika to the ground and grabbed him with both hands, swung him round and thumped him hard against the side of the Sika. Behind him, Linna had followed him, Hietanen and one of his men piled out of their Sika, all of them manhandling the running men, grouping them behind Hakkarainen’s Sika. Seeing a semblance of organisation and the armoured bulk of the Sika’s offering at least a sense of security, more stragglers joined them.

They were all older men, greying, overweight, rear-echelon transport and logistics troops without any real combat experience. Hakkarainen interrogated them sharply, found they couldn’t tell him much, just that a horde of Russians had emerged from the woods, shot up some of the trucks, they’d mostly run without fighting. He sent them back towards the road to join the men already there. “Take any other’s you find with you, mind,” he told them. “We don’t want to leave anyone behind out here. Start getting the trucks ready to move again, get any badly damaged ones out of the way. We’ll clean out the Russians.” Reassured by the presence of the armoured Sika’s and the aggressive confidence of Hakkarainen’s men, the transport men headed in the indicated direction, at least now looking like they were in an army.

Hakkarainen piled back into his Sika. There was fighting going on ahead, that was for sure. Russian and Finnish rifles, grenades, Russian machineguns. Lammio’s joukkue was in action on the right, he could hear the chatter on the Komppania radio net. Koskela was moving down the road, small groups of the transport troops coalescing around his joukkue and clearing out the Russians as he went. As he scrambled up and into the Sika, his driver threw it into first and they move forward.

“Bounding overwatch,” Hakkarainen ordered. “Virtanen, your section leads. We’ll cover you.”

“Move out.”

“Faster.”

“You drive then,” Maatta’s voice was an angry snarl on ther intercom as they bucked through the forested ground, weaving around large trees, crashing through the scrub and the smaller trees. The first Sika, Virtanen’s, crossed a small stream, climbed up the bank, and halted to wait for the others to follow. The gunners looked around, alert. Someone spotted a small group of Finnish soldiers moving back in good order. Hakkarainen shouted out: “You there, where’s the enemy. What strength?”

An NCO ran over. “Where do you want my men? There’s Russian’s back there, no idea how many,” he yelled up at Hakkarainen. More soldiers were trickling in, some running, some seemingly prepared to fight. “Get a hold of these men falling back and move back to the road.”

“Right,” the Kersantti said, and like a shot he was off, rounding up stragglers.

From beside Hakkarainen, Linna chuckled. “He looks happy to be going.”

“At least he was still fighting,” Hakkarainen snapped. Then, as the second ryhmä moved up, “One ryhmä, move out.”

They moved up and over the slight ridgeline, pausing as the second ryhmä moved up and through. Then leapfrogged again. “Ambush”. Virtanen’s voice on the joukkue radio net was very controlled. “Estimate two hundred romeo alpha’s. Taking fire.”

The twin Lahti’s and the 12.7’s on Virtanen’s Sika blazed lines of fire into the scrub and forest as his Sika accelerated into the ambush, closely followed by the other two in the ryhmä, Hakkarainen’s and Lehto’s, the drivers following their training without orders. Behind them Hietanen’s ryhmä was fanning out to the left and accelerating, engines roaring, machineguns and Lahti cannon blazing lines of fire into the trees. Standard training. Accelerate into an ambush and break through, then circle back and criss-cross through the ambush zone machinegunning everything in sight. To either side of One Ryhmä’s three Sika’s moving in their arrowhead formation, Russians bolted. The cannon and machineguns cut them down, Hietanen’s ryhmä now swinging right and driving into the flank of the ambush, rolling it up from the side. Rifle bullets pinging and whining of the armour.

“Don’t stop!” Hakkarainen barked at gis driver. “The others will follow. Just keep on going!”

“Tank. Left. Eleven o’clock,” Linna yelled, swinging his cannon around.

“It’s one of our own panzers!”

“No, its not!”

There was a moment of indecision as the T-26 nosed towards them. No Finnish markings on the front. Still they hesitated. Hakkarainen saw Russian soldiers moving beside the T-26. They wouldn’t be doing that if it was Finnish.

“It’s Russian. Fire!” he screamed.

Although their Sika was still moving, Linna on the Lahti’s fired. Simultaneously the driver braked hard, and the Sika halted. It stopped so suddenly, that the everyone in the back, Hakkarainen, Linna, Salo, Sihvonen and Vanhala crashed into each other and the side of the troop compartment. Regardless, Linna kept firing, keeping the Lahti’s on target. From below, Riitaoja was alternately swearing and crying. Hakkarainen kicked him in th helmet, as much to quieten his own nerves as to shut Riitaoja up, although it managed that as well.

The T-26 halted and it’s cannon began to swing towards them. Virtanen’s Sika opened fire at the same time as Linna opened up. Two streams of 20mm AP rounds hit the Russian T26, which jerked, turned sideways and stopped. The big white number and a red star were clearly visible on the turret. The 20mm shells poured in; every one was a hit. Flames beginning to flicker from the engine compartment. Two more enemy panzers appeared through the trees. One of them stopped abruptly, as if it had run into an obstacle. It had – fire from Hietanen’s ryhmä. Linna’s Lahti jammed. He tried the cartridge-remover, but it slipped, and fell to the floor. The hammer and the screwdriver didn’t work either and went down there with the cartridge-remover. Vanhala joined him, hands bleeding, because of the bolts and the tools slipping as he tried to pry the jammed cartridge out. Lehto’s Sika took out the third T-26. Nobody tried to escape from any of the T-26’s. The 12.7’s chattered continuously, cutting down the Russian infantry.

“Forward,” Hakkarainen ordered.

They moved forward in a line now, weaving around the trees, crashing over logs and through bushes, the guns firing bursts at anything that could hide a Russian, cutting down Russian soldiers mercilessly.

“Cleared,” Linna and Vanhala frantically loaded belts for the Lahti. Linna fired a quick burst at nothing in particular, just to make sure the guns worked. The burst spooked a small squad of Russians who emerged from wherever it was they’d been hiding, right in front of Lehto’s Sika, hands held high. Lehto pushed Kaukonen aside and swung the twin Lahti’s of his Sika’s to cover them and, after an infinitesimal pause, fired a long burst that cut them down. The 20mm cannon shells at close range blew them apart, blood and body parts sprayed in all directions. From the driver’s seat of Lehto’s Sika came a howl of rage. “Sataana, Lehto, did you have to shoot the poor bastards. You can clean the perkele glass, it’s covered in blood and I’m not touching it!”

“Forward,” Hakkarainen ordered again.

They criss-crossed through the ambush zone, then swept back towards the road. Russians were running away from the road, towards them. The guns continued to cut them down. Riitaoja was on the Komppania net, making sure everybody knew they were sweeping in. Nobody wanted to be taken out by their own side’s fire. They reached the road, turned and swept back down the side of the convoy. It seemed Koskela’s joukkue had done a pretty good job. Groups of Finnish soldiers were already recovering the trucks, policing up the wounded and the bodies of the dead, collecting weapons. At the roadblock that had been their starting point, an infantry company was dismounting from trucks and preparing to move out in a sweep through the woods. Their CO walked by, looking at Lehto’s Sika in disgust. The front looked as if it had been painted red, a dismembered arm was stuck in the front grill. Lehto jumped out, walked around to the front, tugged the arm out and looked at it, looked at the infantrymen passing by and grinned. “You men look like you need a hand,” he said, tossing the arm at a young soldier. Who promptly threw up. Lehto chuckled.

Hakkarainen felt inexpressibly weary as he waited while Lehto wiped down the glass. Around him the Sika’s of his joukkue stood, their engines idling, the gunners continuing to eye their sectors warily. Summoning up some energy, from where he wasn’t sure, he got on the radio and reported in to the headquarters section. Kaarna came up on the net.

“Form up and move to the front of the Convoy Hakkarainen, there’s a rear security unit taking over.”

“Acknowedged. Move back onto the road, front of the convoy and form up. Hakkarainen Out.”

He issued the orders to his joukkue. They backed and filled, turned and moved up the road again. The log troopers waved as they went by.

“Well, I’m glad that’s over,” Salo muttered. Hakkarainen didn’t say anything, but he agreed.

(Viewer discretion advised i.e. if bodies are a bit much, don’t watch…..and just do a bit of mental substitution if you’re watching it….)

He wears green boots and he’s coming to get you

Sika on his sleeve and I can bet you

There ain’t no place where a Russkie can run

or hide his face in Karjala-land.

Now he’s quick with a puukko and he’s fast on the draw

and in Karelia he is the law

He don’t know a word of fear,

everybodies safe when a Sika’s near.

He wears green boots and he’s coming to get you

Sika on his sleeve and I can bet you

There ain’t no place where a Russkie can run

or hide his face in Karjala-land.

Put a tracker on him now, in front of the car,

showing us where the Russkies are

There’s one thing you must understand,

The Armiejan is the law in Karjala-land.

He wears green boots and he’s coming to get you

Sika on his sleeve and I can bet you

There ain’t no place where a Russkie can run

or hide his face in Karjala-land.

Repeat chorus.

He was part of a unit, he could do it

As hard as a rock was Eugene De Kock

To say the things that he has done,

made him enemy number one.

He wears green boots and he’s coming to get you

Sika on his sleeve and I can bet you

There ain’t no place where a Russkie can run

or hide his face in Karjala-land.

Excerpt from “Kalmaralli: Puna-Armeijan tuhoaminen Syvärin rintamalla, Elokuu1940” (“Death-dance: The Destruction of the Red Army on the Syvari Front, August 1940”) by Robert Brantberg, Gummerus, 1985.

Having led the Finnish offensive on the Karelian Isthmus through April and May 1940, fighting southwards from their starting point on the Mannerheim Line to the outskirts of Leningrad in six weeks, the 21st Panssaridivisioona, nicknamed “Marskin Nyrkki” – The Fist of the Marshal – had been withdrawn from the Front to reequip and train replacements for the casualties. As part of this re-equipment, two of the Division’s Jääkäri Battalions had been equipped with the new Sika Armoured Fighting Vehicles together with a miscellany of armoured and unarmoured support. Much of June and early July had been spent reequipping and training in the rear and thus the 21st Panssaridivisioona would not be heavily involved in the initial defensive fighting and counter-attacks on the Svir in late July and early August 1940. They, together with the other 3 Armoured Divisions, two of them the newly created Divisions using captured Red Army tanks and equipment, would be held back in reserve, leaving the localized counter-attacks to the Infantry Divisions, who bore the brunt of the fighting through the furious battles of mid-Summer. Their moment to shine would arrive soon enough.

Like the other officers of the 21st, if not the men, newly promoted Luutnantti Hakkarainen fretted at their inactivity through late July as the fighting carried on. Training palled, but worry turned to hope and then to elation as the news of the fighting at last turned positive and Finnish defensive positions were regained, Russian units annihilated or driven back. In the second week of August, the 21st was moved up towards the front and crossed the Svir, halting in the bridge head that the men and the guns of the British Commonwealth Division and the Armiejan’s 8th Infantry Division had forced as the Red Army fell back in increasing disarray under the relentless counterattacks, breakthroughs and encirclements. And now the 12th Infantry Division had moved ahead, breached the weakened Red Army lines, creating an ever-wider gap through which the 21st would pour, the spearhead of the attack, the massed armour, infantry and guns pounding down the road towards Leningrad, two other Armoured Divisions and the Infantry Divisions of the Strategic Reserve thrown in to the offensive while the Infantry Divisons of the Eastern Karelia Army fanned out, rolling up the Red Army’s flanking units, eradicating the rear area support and logistics units. And all the while the men of Osasto Nyrkki and the Parajaegers were deep in the enemies’ rear, cutting communications, eliminating headquarters units, destroying supply dumps, supported by the fighter bombers, bombers, ground attack aircraft and ground attack gyrocopters of the Ilmavoimat in creating havoc. And always overhead flew the air superiority fighters of the Ilmavoimat, dominating the skies, forever watching for any Russian aircraft which dared to approach.

The destruction of the Red Army on the Syvari Front was a prelude to the great “cauldron” battles of Barbarossa. It was to be a classic demonstration in the use of armor in warfare along the lines articulated by some of the early theorists in tank warfare such as Basil Liddell Hart – or indeed, of Tukhachevsky with his “Deep Penetration” theories – finding a weak spot and pouring an “expanding torrent of mobile firepower through it slashing at the enemy in the weak underbelly of his rear echelon, cutting communications and supply lines and driving him into defeat.” As a battle it is now virtually unknown outside of Finland – more or less deliberately forgotten by Russian historians, unnoticed by the British, who were at this time deeply involved in their own struggle for survival and in the midst of what would become known as “The Battle of Britain”. The Germans vaguely noted the Finnish victory but saw it merely as part of the ongoing Finnish defeat of the Red Army – a sign of weakness that predicated the success of their own inevitable offensive against the Soviets. For the Americans, the battle was a footnote in history, noted for a day by the military attache’s in Helsinki and duly forgotten. The senior officers of the British Commonwealth Division, who were heavily involved in the battle, took lessons from it but were never in a position to apply those lessons during WW2.

Ukkosvyöry: Tuulispäänä Leningradiin

Kapteeni Kaarna was injured by a stray Russian artillery burst as they moved up towards the front after crossing the Syvari. It was a fluke. Battalion HQ had ordered a halt to refuel and replenish ammunition before they moved up to their start positions. They’d paused at the designated point, waiting for the log vehicles to catch up, Kapteeni Kaarna had ordered an impromptu Orders Group when a few stray Red artillery rounds dropped in. First, the evil shrieks of the shells, then violent explosions off in the forest to their left which set the earth quaking, trees toppling. The men were ducking for cover either in or out of their Sika’s. Lammio and Hakkarainen dived to the ground, Hakkarainen wriggled a little further into a slight depression, Lammio hiding behind the illusory protection of a tussock of grass. Koskela was running back to his Joukkue, Kaarna continued to stand there, looking down at them, a bemused smile on his face. “Just random artillery,” he said quite calmly, “not aimed at us.”

Ashamed at seeking cover while the Kapteeni continued to stand, Hakkarainen was about to rise to his feet when something exploded very close. The ground heaved, a crashing explosion half-deafened Hakkarainen, a shower of dirt enveloped him, and as he struggled to brush the dirt of his face, he half-sensed the Kapteeni and Mielonen, the Kapteeni’s Orderly, collapsing. As Hakkarainen struggled to his knees and then to his feet, Mielonen rose instantly and stumbled to where the Kapteeni was lying motionless, his body strangely twisted. Mielonen knelt beside him, deathly pale, calling out in a shaky voice. “Medic …. Medic ….. Quickly, Quickly ….He’s bleeding ….. Quickly!”

Hakkarainen and the Medic from the Kapteeni’s HQ Sika arrived simultaneously. Hakkarainen carefully turned the Kapteeni over on his back and the men saw that one leg was bent unnaturally to the side. Kaarna had taken a direct hit and only the tattered cloth of his breeches kept the leg from falling off altogether. Dully, Mielonen mumbled as if to himself: “Got me in the arm too …. Got me, too ….. Medics …… where the hell are they …. Medics!”

A couple of the men moved Mielonen out of the way, cut the sleeve of his shirt, began to apply emergency dressings to his arm. The medic and Hakkarainen worked furiously on the Kapteeni, Hakkarainen frantically trying to remember his first aid training as the Medic issued instructions dispassionately. The medic had wrapped a tourniquet round what was left of Kaarna’s leg, stopping the bleeding, Hakkarainen was working to keep it on while one of the men applied a pressure pad to the stump. The Medic had found a vein, stuck a needle in and was frantically fitting a bottle of distilled water to the tube as one of the soldiers with medic training worked to reconstitute a 400cc bottle of freeze-dried plasma. The three minutes it took to reconstitute seemed like a lifetime, but the distilled water kept the blood volume up enough to keep his heart beating. As soon as the plasma was ready the medic had it hooked on to the drip with a second unit already being prepared. Kaarna’s eyes opened and looked around, his mouth working. Hakkarainen took one of his hands, leaned in above him. “You got hit sir, medic’s getting you stablized.” In the background, Hakkarainen could hear Lammio talking urgently into the Radio, then yelling at the men. “Clear the road and mark a strip, one of the Storch’s is on its way, be here in ten minutes.”

It was the longest ten minutes of Hakkarainen’s life as they poured unit after unit of reconstituted plasma into the Kapteeni, redid the tourniquet on his leg, dusted the stump with sulpha powder, reapplied pressure pads and bandages, injected morphine, checked for any other injuries. The Storch arrived in nine minutes, sinking down to the narrow strip of road and landing almost next to them. Even before it had stopped an armiejan doctor was out the door and running towards them, medical pack in hand, yelling instructions at the men to bring the stretcher from the Storch over. Kneeling beside them, he did a quick check, nodded his approval and opening his pack, retrieved a bottle of Fresh Whole Warm Blood from his cooler and swapped it in, removing the almost empty plasma bottle. By the time he’d pumped a couple of 1 litre bottles of real blood in, Kaarna was looking more like a casualty and less like a corpse. They moved him tenderly onto the waiting stretcher, strapped him down, waited while the Doc fitted another unit of Fresh Whole Warm Blood and then loaded him into the Storch, the Doc dancing attendance the whole time. He looked out at Hakkarainen just before they shut the door and grinned. “He’ll make it now,” he said. “You men did everything right., never lost a man yet that was in this good shape.” The door shut, the Storch lifted almost vertically, banked over the treetops and was gone.

Hakkarainen stood, looked around, realized his hands were shaking. Kersantti Lehto was beside him, his face as expressionless as ever, proffering a pack of cigarettes. Hakkarainen opened his mouth to say he didn’t smoke, then snapped it shut and started to take one, found he couldn’t get it out of the pack. Lehto flicked the bottom of the pack with one finger, Hakkarainen managed to take the cigarette that popped up, put it to his mouth and gratefully accepted the flaming match that Lehto held to the tip. The cigarette smoke was strangely soothing. Hakkarainen noted that his hands were no longer shaking. Lehto looked at him for a moment, as if checking that he was all there, then turned and walked away. Lammio was beckoning him over. “Battalion CO on the RT,” Lammio said sourly, “He wants a word.” Hakkarainen took the proffered headset and mike.

“Alpha One Leader acknowledging” he said.

Majuri Sarastie came up. “You’re in command replacing Kaarna. You’ve got a field promotion to Kapteeni. I’ve told Lammio. I’m sending you up a replacement for your Joukkue. Be prepared to move out in an hour.”

Hakkarainen blinked. “Alpha One Leader acknowledging, take command, be prepared to move out in an hour. Out.”

“Good man,” Sarastie said. “And good work getting Kaarna patched up. The Aid Post called in to say he’s good, they got him stable and he’s being moved to a Field Hospital for emergency surgery. Tell the men he’s going to make it. BUT! From now on, remember patching up the casualties is the Medic’s job, not yours. You should have taken command right away. No damage done so you’re forgiven. Once. And Kaarna, he’s going to be a hard act to follow, so don’t fuck up on me. Out.” He cut out.

Hakkarainen handed the headset and mike over to the waiting Sig. Lammio still looked sour. “Any orders Sir?” he asked.