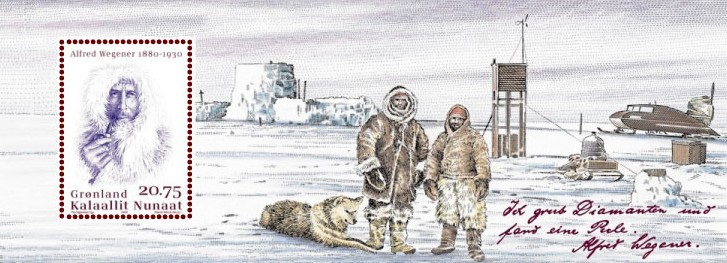

22nd May 2006 commemorative stamp and cancellation from both Germany and Greenland remembering Alfred Wegener. Note the Finnish-designed and built aerosled on the right.

In 1929, two Aerosleds were purchased from the Finnish State Aircraft Factory, Valtion Lentokonetehdas for a German Arctic expedition in Greenland led by Alfred Wegener over 1930-31. The history of those Finnish Aerosleds and the people involved in designing, building and using them has been by and large forgotten for decades. Although there has been some intermittent research and documentation, this exists only in fragments that are available here and there without a complete picture and are generally recounted only in reference to the Wegener Expedition. The focus of this article is on the story of these amazing Finnish Aerosleds, capable of travelling in ideal conditions at speeds of up to 100kmh over the ice while carrying two men and a payload of up to 800lbs of cargo, their antecedents, their use in the ice and snow of the Greenland ice cap and the use of their descendants in the Continuation War which was fought between Finland and the Soviet Union over 1941-1944.

To start of this story, we go back in time almost one hundred years, to 1919. In newly independent Finland, Valtion Lentokonetehdas (the State Aircraft Factory) began building aerosled’s (“moottorireki”) from immediately after the new state was created. In 1919, aerosleds were themselves a fairly revolutionary means of transport, first used in the early years of the twentieth century, they had been popular in the old Tsarist Russia and this is possibly where the idea for the first Finnish aerosleds originated. Regardless of where the idea came from however, we know that a prototype aerosled had been built at Suomenlinna in 1919 by Asser Järvinen. This earliest of Finnish Aerosleds was a large (and heavy) three-ski design that could carry 15 persons and was powered by a 150hp Benz engine.

The 3-ski Aerosled design and built by Asser Järvinen in 1919. A 15-seater, it was powered by a 150hp Benz engine. It ran between Helsinki and Santahamina over the 1920’s. Photo courtesy of Feeniks, the magazine of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society (http://www.imy.fi/)

As can be seen from the photo above, this Finnish-designed and built Aerosled from 1919 was large and appears to have been steered using the single rear ski – which could be easily turned if it hit a large piece of ice or stone. In 1921, a Finnish Jäger named Arvo Tenlenius (he changed his surname to Tervasmaa in 1935) was transferred to Santahamina and after seeing Järvinen’s Aerosled, would go on to further develop aerosled designs. Arvo Tervasmaa, as we shall refer to him from now on, came from a farming family in the hinterlands of Kisko and Karjalohja in the province of Uusimaa. After studying at the Lyceum Ateneum, Tervasmaa had worked as a mechanical engineer. In November 1915, in the midst of World War One, the 24 year old Tervasmaa made the perilous trip from Finland to Germany, skiing across the frozen Gulf of Bothnia to Sweden and thence to Germany to join the Finnish Jääkari – Finnish volunteers fighting with the Germans in order to free Finland from the oppressive yoke of Russian rule. Tervasmaa fought in the ranks of the 27th Jaeger Battalion (the Finnish volunteer unit fighting with the German Army) and while there, attended a number of courses where was trained on almost all the future means of transportation: cars, motorcycles, caravans and tractors to pull heavy assault guns.

When Finland at last gained her independence from Russia, Tervasmaa would return with most of his fellow Jaeger volunteers to fight with the White forces in the Finnish Civil War, the conflict between the Whites and the Reds which was decisively won by the Whites. After the Civil War ended and independence was secured, Tervasmaa ended up in the fledgling Finnish Air Force and in 1920 was appointed commander of the NCO School at Utti. In the following year, 1921, he was transferred to the Santahamina Yard of the State Aircraft Factory, where he worked under Asser Järvinen and would no doubt have seen and traveled on the aerosled Järvinen had built in 1919. At Santahamina, Tervasmaa’s natural tendencies and technical abilities came to the fore and he got his start working in his own right in the field. The technical nature of the branch had attracted Tervasmaa to the air force and the air force would make full use of his ingenuity and ability throughout his entire career with them. While Tervasmaa’s early ambition on joining the air force had been to become a pilot, his flying career unfortunately ended after his first solo flight. According to his son Antti Tervasmaa’s account, he was grinding in the Santahamina machine shop when a chip flew into his eye and so damaged his vision that he was forced to stop flying. Thereafter, he gave up his pilot’s career and went on to serve a full 25 years without interruption in responsible engineering management and aircraft inspection duties in the Air Force. After resigning from regular service, he continued as Technical Director & then Managing Director of the Kupio Amnnunition Factory for a further 10 years (from 1946 to 1956).

Tervasmaa’s life work was undoubtedly management of the Civil Aviation Yard at Santahamina (later the State Aircraft Factory at Santahamina). Already at this time Lieutenant Asser Järvinen had performed engine design work for the domestic airline industry. Järvinen had also assumed responsibility for the air force’s aircraft repair work, responsibility for more and more of which fell on Tervasmaa’s shoulders. Tervasmaa was assigned many difficult tasks and kept very busy, but he had the desire and the enthusiasm to succeed, as well as good eyes and a sure instinct for technical matters. His relative age and experience also contributed to his sound judgement. Finland at this time simply did not have many men trained in this field and Tervasmaa stood out. He worked incredibly fast, himself training a large number of workers in even the smallest tasks and making these workers into capable assistants. It is during these times among the pilots in Finland that the saying “ettei konettä niin rikki saakaan, ettei sitta vielä Telakalla uutta tehtäisi, joten säkkiin vaan ja Santahaminaan” originated (“you can’t break a plane so much, that the Yard can’t make it as new, so put it in a sack and send to Santahamina”).

At this time, early in Finland’s aviation history, all airports (with the exception of Uttia) were located on the waters edge. Aircraft operated using floats in the summer months and using skis to fly off the ice or snow in winter. This necessitated moving personnel around on the water using boats – and in winter, personnel needed to be moved over the ice and snow-covered off-road areas in a similar fashion. At Santahamina, early transport across the ice was by horse-drawn sleigh but as Santahamina grew, running a scheduled service beyween the aircraft factory and Helsinki demanded something more tangible than a one horsepower sleigh. In 1919 the Aviation Factory built a small motorized sleigh, which gave the Factory some good experience. Director Järvinen then designed a solid ski and a 15-person sled (as seen in the photo earlier in this article). When running on a hard, flat surface it worked well, but the skis were not suited to use on heavy snow or on rough surfaces.

An early Tervasmaa aerosled – this was an open 8-person motor sled used for the Santahamina transport service. In favorable conditions this sled could reach a of speed 100-120 km/h.

From this point in time, further design and development of the aerosleds was left to Tervasmaa. His first aerosled was also a three-ski machine, but all the following models he designed and built were constructed with four skis, with two flexible skis used for steering at the front, while the weight of the motor at the rear rested on the two fixed skis. This four-ski design had the great advantage that the rear skis were heavily loaded and slid gently while the front skis carried less weight and were used for steering. Tervasmaa built the skis to be as flexible as possible, so they could handle uneven terrain smoothly. But probably the most important part of the designed was Tervasmaa’s load-bearing framework – the actual load-bearing part formed tray sides, such as much later has been a guiding principle for many well-known car designs.

Tervasmaa also became interested in the design of aircraft skis. Skis on Aircraft had been used by many countries before they were used in Finland – in Russia, Sweden and Germany, and probably in Canada to name only a few. In Estonia, German aircraft visited in the winters of the early 1920’s and also during the winter season visited Santahamina. Tervasmaa at least saw that skis were not well designed and built. Pilots had great difficulty to turning planes on ground and when lifting off the ground into the air. The skis were way too heavy and of a constant width. Tervasmaa would go on to design skis for aircraft which were exported in large quantities to Sweden (to the Junkers subsidiary AB Flygindustri), to Czechoslovakia and to Canada. The Tervasmaa ski was narrower towards the rear, light, and above all flexible. The main idea was the same as cart (car) springs and the goal was to attain the most flexiblity possible, so that the ski in spite of the lightness would work well on uneven surfaces and snow drifted landing places.

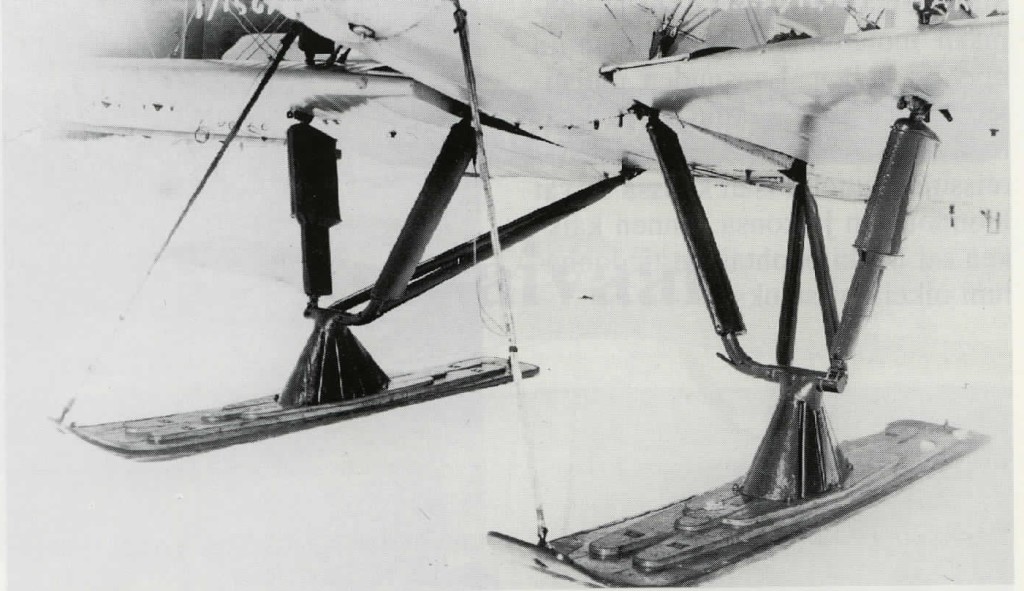

Most likely introduced in the mid-1920’s, and certainly earlier than 1927, these skis were later manufactured by the Aircraft Factory of Karhumäki Brothers. They remained the standard ski of the Finnish Air Force for decades and were used almost unchanged at least until the late nineteen fifties. This ski type is best recognized by the enclosed attachment bracket, which is a complicated welded steel sheet construction and is bolted through the ski. The ski was made of separate blanks of pine wood while the underside was clad with sheet metal, which was bent over the edges. This ski also had a tapered blunt nose. The photo immediately below shows these skis on a Finnish aircraft – in later photos of the Finnish Aerosleds used by the Wegener expedition, you will see the identical skis and ski mountings – a unique characteristic which incidentally makes Finnish-designed aerosleds used in the Continuation War easy to identify.

Tervasmaa’s aircraft ski design, seen here on a VL Kotka. Photo courtesy of Feeniks, the magazine of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society (http://www.imy.fi/)

After having received a number of flattering statements regarding his ski design, Tervasmaa filed a patent for the ski and struts, but the application was rejected already at the first stage (by the Air Staff). The patent application was returned with a short remark, that “design was a part of duty, and does not justify special compensation”. There was of course the possibility that the patent would have been applied for in the name of another person, but that kind of arrangement was not customary in those days.

Aerosled Designer and Builder, Arvo Tenlenius (he changed his name to Arvo Tervasmaa in 1936) with his wife, Helmi Tenlenius and daughter Hillevi (future glider pilot and wife of SAAB engineer Per Schalin). Photo courtesy of Feeniks, the magazine of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society (http://www.imy.fi/)

Arvo Tervasmaa (3 October 1891 – 17 January 1963) was a Finnish Jäger Major who had studied at the Lyceum Athenaeum (the Drawing School of Finnish Art Society in the Ateneum building in Helsinki) over 1907-1908, then worked from 1909 – 1911 as an assistant branch manager for Westerlund & Co. Between 1913-195 he worked in mechanical engineering at Wilhelm Schauman Ab Pietarsaari before joining the Jäger volunteers undergoing military training in Germany. Tervasmaa underwent a baptism of fire fighting against the Tsarist Russian Army on the Eastern Front at Misse River and on the Gulf of Riga in 1916 where he was wounded. After his injuries healed he was placed on a number of German Army training courses for motorboats, motorcycles, motor vehicles and the tractors used to pull heavy assault guns. He went on to fight in the Finnish Civil War as an NCO (Company Sergeant-Major) with the White Army where he took part in the battles of Lempälä and Sainio, as well as the recapture of the city of Viipuri.

After the Civil War Tervasmaa remained in the Army and in January 1921 he was transferred to Utti Airport and placed in charge of NCO training. In March 1921 he was assigned to the Aviation Factory at Santahamina, where he became Head of Civil Aviation. He began flight training but had to stop after his first solo flight (according to his son, Antti Tervasmaa, he was working in the machine shop when a chip flew into his eye and damaged his vision so much that he could no longer fly). He completed study trips to explore the aircraft and engine industry in France in 1924, Germany in 1929 and in Czechoslovakia in 1931. He also attended an Aviation Engineering course in 1933. In January 1928 he was appointed Head of the Santahamina Aviation Factory and in 1937 he was transferred to Flight Regiment 1 and promoted to Captain (he was the Flight Regiment’s Engineering Officer), a role he served in over the course of the Winter War where he fought on the Isthmus as Air Force engineering manager.

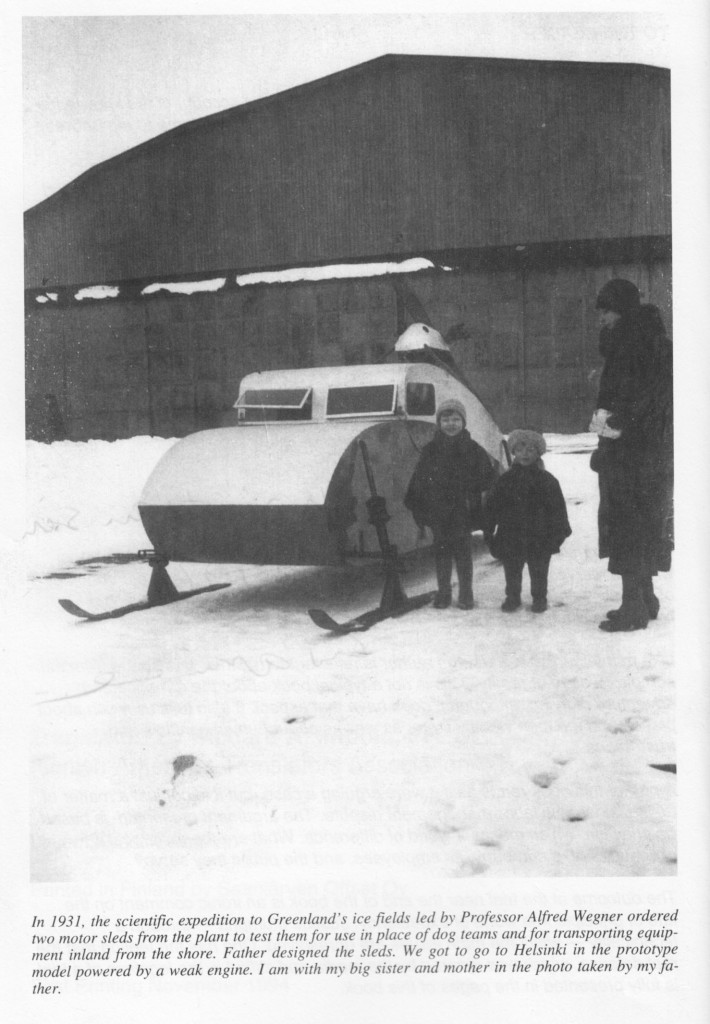

the son of the then Director of the Finnish Aircraft Factory with one of the Aerosleds in Helsinki (photo courtesy of Danish Museum of Science and Technology and taken from Antti Tervasmaa’s autobiography)

Through the 1920’s, Valtion Lentokonetehdas (the State Aircraft Factory, aka VL) went on to build several three-ski and four-ski models, generally powered by 100 hp aircraft engines. These aerosleds were all designed by Tervasmaa. Several of these machines were delivered to the Air Force, others to the Border Guard and most with a capacity for 8-12 passengers. Some of the vehicles built for the Border Guard were armed, most saw routine winter use. Their maximum speed exceeded 100 km/h in optimal conditions. In the 1930’s, a number of eight-man aerosleds, a 12-man armed aerosled and even a 15-man aerosled were built. A 12-person aerosled was operated on Pohjoissatama – Santahamina route on a regular schedule. A special covered and armed sled was designed and built for the Border Guard and Finnish aerosled fame spread quickly through the Nordic countries and even as far as Germany.

Kapteeni Väinö Bremer esitteli 6.2.1928 Näsijärven jäällä lentokelkkaa, jolla oli tarkoitus ryhtyä välittämään matkustajaliikennettä Kuruun ja Teiskoon. Kuvaaja: A. Tammine. Photo sourced from: http://www.museosolmu.fi/sites/default/files/imagecache/585/AL115_2.jpg

At some stage in the late 1920’s, Tervasmaa designed a new aerosled with an enclosed cabin which would become the prototype for the aerosleds used by the 1930/31 Wegener Expedition to Greenland and would also, from the photographic evidence that remains, be used by the Finnish military through World War Two. The photo here is taken from Tervasmaa’s son’s (Antti Tervasmaa) autobiography and shows a prototype. The skis differ markedly from the later aerosleds, as do the windows. Nevertheless, it is clearly the ancestral design of the aerosleds used by Wegener in Greenland and by the Finnish military in WW2.

Somewhat incidentally, Tervasmaa however wasn’t the only Finn designing and building aerosleds. The photo on the left shows a motorised icesled introduced by Captain Väinö Bremer in 1928 which was intended to carry passenger traffic from Tampere to Kuru and Teisko. This water route was very important and busy at the time especially for the farmers in Kuru and Teisko through which they brought their products to Tampere. Also local children studying in Tampere high schools traveled home for weekends using steamships (or, it seems, an aerosled in winter) where possible. I haven’t been able to track down any further information on this aerosled but it does at least show that they were not that uncommon along the Finnish coastline and were an accepted form of transport.

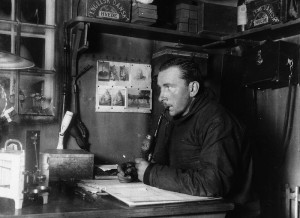

Returning now to Tervasmaa’s aerosleds and their use by the Wegener Expedition to Greenland, Professor Dr. Alfred Wegener was a German scientist who is today better known for his Theory of Continental Drift. Wegener is perhaps less widely known for his enthusiastic contributions to climatology and meteorology, which led to his death on the Greenland ice sheet in 1930 under the most heroic circumstances.

Alfred Wegener pictured during the expedition to Greenland of 1912-1913. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

As a young man Alfred Wegener was a member of the Danmark Expedition (1906-1908) led by Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen and assisted in the exploration of North East Greenland, where he had to witness the tragic death of three participants. In 1912 and 1913 Wegener had successfully wintered with a Danish expedition on the inland ice near the north-east coast of Greenland at the station “Borg”. He then crossed the Greenland ice-shield at its widest extent on an expedition led by Johan Peter Koch during which he got into life-threatening situations on several occasions. This expedition inspired him to undertake his two final Greenland expeditions in 1929-1931, which were only be concluded successfully due to the generous help of many Greenlanders and Danish officials. The memory of these expeditions is still kept alive today by a commemorative plaque and an exhibition in the museum at Unmmannaq on the west coast of Greenland, and by the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany.

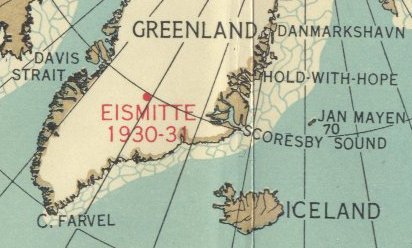

The American meteorologist Professor Hobbs had worked in Greenland, and had formulated theories to explain the formation of cyclones and the causes of weather-changes over the Atlantic and Northern Europe. To test these theories – especially the assumption of constant high air pressure – above the central ice masses of Greenland, Wegener proposed to erect a mid-ice station in conjunction with coastal stations on the same latitude in the east and west and in 1930 he led a large expedition to the Greenland ice sheet to do just that.

Eismitte Base, in the centre of the Greenland Ice Cap at a height of 10,000 feet and 400km from the coast and the west station on the margin of the Inland Ice at Seheideek in Qaumarujuk fjord, Umanak district.

A major innovation in Dr. Wegener’s planned German scientific expedition to the Greenland inland ice cap was to use propeller-driven aerosleds in addition to dogs for transporting supplies from the coast to the expedition’s Central Station. Aerosleds were a new idea for polar transportation and while they had been in use for twenty years, they had not yet been tested in a polar expedition environment in harsh winter conditions. The potential advantages were sufficient to make the motor-driven aerosleds an attractive option. Unlike dogs, which would have to be fed all winter, the motor-propelled aerosleds would only require enough fuel to get them there and back and would require no fuel when not in use. The biggest advantage of motor aerosleds was that more trips carrying more weight could be made to provision the central station. Wegener estimated that the aerosleds could make the round trip in six days, whereas dogsleds required three or four weeks for the same trip. Much of the excitement surrounding the expedition at the time related to the testing of these aerosleds. With the expedition itself now remote in time and without any documentary evidence, it is unclear how Wegener became aware of the Finnish-designed and built aerosleds, but regardless, the fact remains that he commissioned two snowmobiles to use and test alongside dog sleds for his planned 1930-31 Arctic expedition in Greenland. This was the first trial to use a snowmobile in the most difficult of Arctic conditions.

One of the Wegener Aerosleds is being carried out of the Santahamina Aviation Factory’s top floor. Photo courtesy of Feeniks, the magazine of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society (http://www.imy.fi/)

The Official expedition report, published in Germany in 1933 as the book “Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen / Greenland Expedition of Alfred Wegener 1930/31 ” describes the snowmobile experiences in over 30 pages in the chapter ” Die Propellerschlitten”. Roger McCoy’s book, “Ending in Ice” (the story of Wegener’s expedition) relates the story of the expedition and the part played by the aerosleds in some considerable detail, again using the expedition’s book as the primary source. The story of the expedition is indeed fascinating, but this account concentrates instead on the aerosled’s themselves and on their designer and builder, Arvo Tervasmaa, so we shall digress no more.

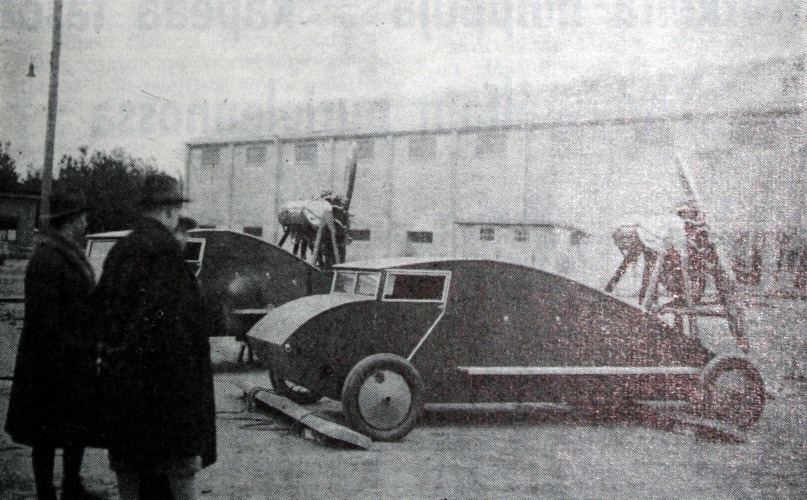

The Sleds for the German expedition to Greenland in front of the yard in Santahamina ready for delivery in March 1930. The wheels were only fitted temporarily in order to facilitate movement. The Skis were of hickory wood. Snowmobile maximum length 5.5 m, skis 2m. The engine was an air-cooled rotary Siemens Sh 12-112 hp. The main tank held 200L, the top tank 15L and the oil tank 16 liters. Enough for 6.5 hours of driving. The Snowmobiles transported heavy loads in difficult conditions.

The two aerosleds used by Wegener’s expedition were manufactured by Valtion Lentokonetehdas (the Finnish State Airplane Factory). Finnish aerosleds were originally designed for winter transport over flat sea ice to offshore islands in the Gulf of Finland and the Bothnian Gulf as well as on Finnish lakes and in these conditions they performed well. Tervasmaa modified his aerosled design for the Wegener expedition and use for oversnow transport, building the two aerosleds for a combined cost of 30,000 German marks. Wegener’s advisor on engineering matters, Asmus Hansen, went with Kurt Schif, who was to be in charge of assembling the motor sleds, to visit the factory in Helsinki, Finland. They were pleased when they saw the bright red sleds finished and ready to be packed in large wooden crates. The sleds resembled a small airplane body with a rear propeller. They ran on four hickory skis, using the front skis to steer like a car.

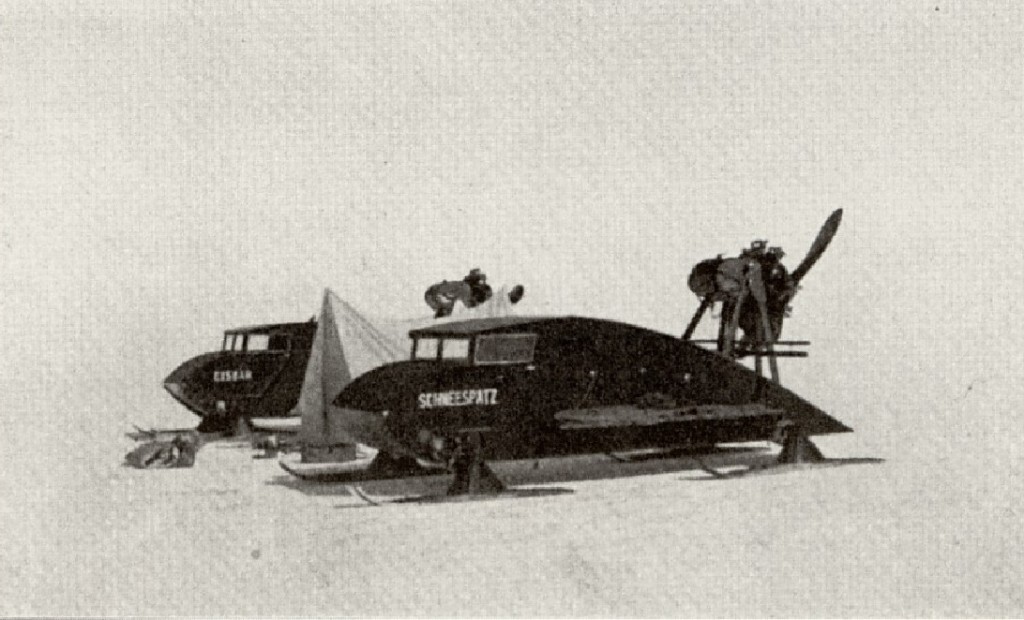

As mentioned above, Tervasmaa’s son, Capain Antti Tervasmaa, mentions in his autobiography that as a young boy, he got to ride in the prototype to Helsinki. In examining the photo of the prototype and comparing to this and later photos we can see how the design of the aerosleds has evolved. The windows are shaped differently and look to offer better visibility, we can see the bench down the side and in later photos the improved Tervasmaa ski design for aircraft is also in evidence. The two aerosleds for the Wegener Expedition were christened Schneespatz (“Snow Sparrow”) and Eïsbar (“Ice Bear”) and looked something like a giant toad with a huge propeller mounted on the back and running on four broad skis. The front skis could be turned like the wheels of a car and were used to steer. The aerosleds were approximately 2m wide and 6m long, with a pilot’s cabin for two persons. The body was constructed of plywood on a steel frame. The propeller was placed at the rear with a motor (a rotary Siemens-Sh-12 radial) developing 112 horsepower engine and carried a 63-gallon fuel tank. The Aerosled without the motor weighed 250 kg and it was therefore heavy work to transport the aerosleds, the motors and the fuel from the sea up the heavily crevassed Qaumarujuk glacier to the margin of the Inland Ice at Scheideck at an elevation of 972 m.

Packing Case containing one of the Aerosled’s being offloaded. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

One of the Aerosled’s has been removed from the packing case and is resting on the ice. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Motorschlitten “Eisbär” und “Schneespatz”; dieser Typ Propellerschlitten wurde ursprünglich in Finnland hergestellt von “Finnish State Aircraft Manufaetory” – zur Überquerung des Bottnischen Meerbusens; Maße: ca. 2 x 6 m; Kabine für 2 Piloten; Stahlrahmen mit Sperrholz; Motor: Siemens-Sh-12; 112 PS; Schlittengewicht ohne Motor: 250 kg; Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Nearing the Ice Cap. The winch in the foreground was used to move the Aerosled up the glacier. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

The Aerosleds first needed to be moved up the Glacier and onto the Ice Cap before they could be used. Photo courtesy of filmclip from the Alfred Wegener Institute.

The aerosleds occupied a key position, for they were the object of great expectations. Wegener was full of enthusiasm about the possibilities of transporting large loads across wide stretches without stopping and in planning the setting up of the Eismitte base, great reliance was placed on utilizing these two machines. The Finns used motor sledges with great success to travel between islands off their coast in winter, but travel on the Greenland Ice Cap was far different from travel on sea ice in the Gulf of Finland and the Bothnian Gulf. The detailed diary entries from August and September 1930 provide an impression of the drama and the difficulties that confronted Wegener.

Things started of badly. Though the main party arrived in western Greenland on April 15, harbor ice hung on stubbornly until June 17, when they were finally able to land their 98 tons of supplies at the base of the ice cap. They were already 38 days behind schedule when they began to move up onto the ice cap to set up the western camp. On July 15, a small party headed inland, establishing the mid-ice camp, “Eismitte,” on July 30. It was 250 miles inland at an elevation of 9,850 feet. (The eastern station was established later, by a separate party that landed on the east coast.) Because of unusually frequent bad weather, only a fraction of the supplies meteorologist Georgi and glaciologist Ernest Sorge would need for the harsh Greenland winter reached Eismitte in the next month and a half.

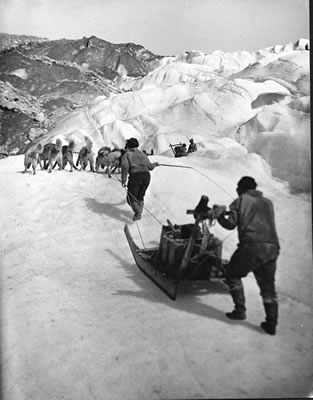

Initial movement of supplies was carried out by dogsled. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

The aerosleds were intended to reduce the human work load, but first they had to be manhandled up to the ice sheet, requiring building a rough road up the glacier. They were far too large and heavy to be loaded onto dogsleds and so they were pulled by ponies across the sea ice and up gentle slopes. Where the slopes were steeper, they had to be dragged up using hand-powered winches and cables. By this means the two aerosleds were moved up the glacier to the edge of the inland ice sheet at an altitude of 2,950 feet. Once at the top of the glacier, the engines needed to be installed and shakedown runs carried out. The conditions of the Greenland Ice Cap were rather different to the flat sea ice of Finland, shakedown runs would be needed to establish the capabilities of the aerosleds in different snow conditions, on uphill runs (for the journey from the edge of the ice cap to Eismitte Base would be a constant uphill run, climbing from 3,000 to 9,000 feet).

The aerosleds were not much brought into use at first, with dog teams being used more. The first dog-sledge expedition into the interior carried only the most necessary equipment, so that meteorological observations might begin as soon as possible. Other dog teams followed later with more provisions and equipment. The trail was marked with black flags, and with posts every five kilometres. The aerosleds followed, but travel at sea level was rather different from travel at several thousand feet above sea level and on the ice cap rather than on sea ice.

There were many concerns with progress. Not only was the expedition starting out six weeks later than planned, the aerosleds took longer than planned to move, assemble and test and their load carrying performance was uncertain. By 29 August the aerosleds were assembled and their motors were running for the first time. While dogsled parties made the first trips to establish Eismitte, the aerosleds were expected to carry the remaining four tons of supplies. Expectations were high. The aerosleds were expected to travel much faster than dogsleds, carrying 880 lbs of cargo plus a crew of two.

Travelling on the ice cap however proved to have its challenges. Every time they stopped the skis froze in place and had to be chipped loose (this problem was solved by placing boards under the skis when they stopped). The sledges were often buried in snow or frozen in during inclement weather. If the skids weren’t encased in ice and snow, then the propeller or engine frequently froze up. Their fuel consumption was high in the deep, soft snows that fell on the icecap, especially if the driver had a difficult time following the trail. The aerosleds had to zig-zag up uphill slopes, making compass navigation difficult. The aerosled engines were not powerful enough to push the loaded aerosleds uphill through drifted snow. Driving into the strong winds which blew down off the ice cap also slowed the aerosleds down.

Unexpected crevasses added their own element of danger. Regardless, Curt Schif and Georg Lissey, in the Schneespatz, and Franz Kelbl and Manfred Kraus, in the Eïsbar, set off from the 53-mile depot for Eismitte. Much of their load and additional fuel had already been cached at the 125-mile depot (by the dog sled team), which they reached in five hours. Nevertheless, conditions encountered meant that they had to turn back. They tried again on September 2nd, but found that making good progress was heavily dependent on the winds, especially when travelling upslope.

Members of the expedition with one of the Aerosleds – the proximity of the men next to the Aerosled gives a good idea of size. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

A third attempt failed because of bad weather and a fourth attempt was made on September 5, when they made good progress. For the first 30 miles the aerosleds travelled at little more than a fast walk but where the slope flattened out and the snow became drier they began to reach speed of up to 15 mph. They found that the aerosled engines were not powerful enough to drive the sleds upslope except in ideal conditions – calm winds, dry snow and gentle slopes.

The fourth sled trip established fuel and supply depots along the route to Eismitte, with each aerosled making trips in stages to the halfway depot over a period of a week. In this time they managed to cache 2,700 lbs of supplies at the halfway depot. During this work they discovered a number of problems with operating the aerosleds. In the low temperatures of the ice cap, carburetors and fuel lines froze and engines were hard to start. A fuel leak occurred and a repair had to be improvised using string, tape and wire.

An Aerosled photographed against the vastness of the Ice Cap. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Camping on the Ice Cap, Aerosled in foreground with open cargo bay visible. You can also clearly see Tervasmaa’s ski’s. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Propeller sledge Schneespatz buried in snowdrifts after a snowfall. Conditions on the Ice Cap at times made progress impossible…. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Unexpected crevasses added their own element of risk and slowed progress. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Another photo of “Schneespatz” and “Eisbar” on the Greenland Ice Cap. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

At the half-way depot they met the Wölcken and Jülg party returning from Eismitte. The next morning the aerosled crews were beset by thick mist and driving snow. While the dog teams, which could travel in virtually any weather, left for Scheideck, the aerosled party had to wait. They could ill afford to get lost under those conditions. For three days the aerosleds were snowed in. When the weather improved on the 20th, After the weather cleared, it took an entire day to clear, heat and start the engines – the Eïsbar’s engine started with difficulty, while the Schneespatz’s engine would not budge. Eventually it yielded – after being heated for an hour and a half by a primus and soldering lamps – but the men were too exhausted to do anything else after hours of struggle at 8,200 feet. A further day was needed to dig out the runners and get the aerosleds moving. Before they could start out, they were hit by another blizzard and again could make no progress. On the 22nd, the weather improved, but the heavy drifts of deep fresh snow and fierce headwind prevented the aerosleds from making any progress toward the east.

There was no way the aerosleds could make Eismitte with a heavy load and then complete the return trip. Thus, only a few hours of travel away from their destination and running out of their own supplies, the aerosled crews made the decision to unload and cache the cargo and return to the West Station at the edge of the ice cap.

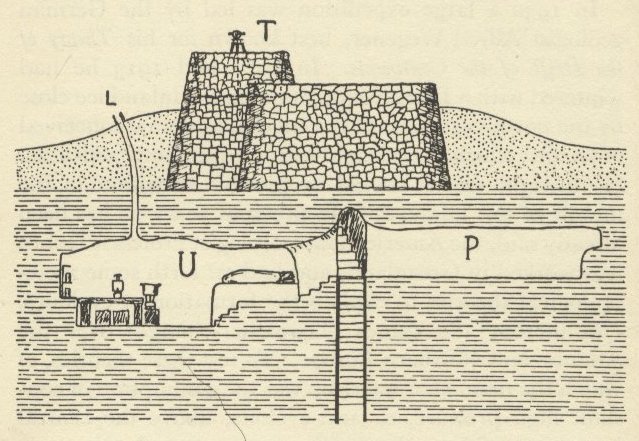

Eismitte Station: resembling more a Roman fort than any igloo, the station comprised an excavated section and an observation platform. From the observation platform, via a sheltering wall, an entrance and steps led down into the ice where a store-room and winter quarters were constructed. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Not enough equipment had been carried to Eismitte base last for the remainder of the year. The boards intended for lining the ice-cave remained at the coast together with the radio transmitter. Provisions were still not truly sufficient by the end of Arctic summer to last through the winter. At that latitude the sun does not set between May 13 and July 30 each year, and does not rise between November 23 and January 20. On September 21 Wegener himself led a 15-dogsled run to relieve Eismitte. He was accompanied bv fellow meteorologist Fritz Lowe and 13 Greenlanders. Because of poor snow conditions and bad weather, however, they covered only 38.5 miles the first seven days. Wegener wrote it was now “a matter of life and death” for his friends at Eismitte. As the relief party continued to struggle eastward, all but one of the Greenlanders gave up and returned to the base camp. Wegener and his two remaining companions finally reached Eismitte on October 30, after traveling for 40 days. For the last five days temperatures had averaged -58 degrees F and a constant, frigid wind had blown in their faces.

A diagram of Eismitte station: T – theodolite for balloon observations, P – provisions store, U – underground accomodation for three men, L – airshaft, In the centre, a shaft leads deeper into the ice for scientific investigations

At Eismitte, the travelers were delighted to find that Georgi and Sorge had been able to dig an ice cave for shelter; moreover, they thought they could stretch their supplies through the winter. The heroic rescue run had been unnecessary, but there had been no way to let Wegener know as there was no radio. Although Eismitte was successfully re-provisioned it could support only three men. Fritz Lowe was exhausted and his feet and fingers were badly frostbitten. Wegener, on the other hand, “looked as fresh, happy and fit as if he had just been for a walk,” marveled Ernst Sorge. “He was fired with enthusiasm and ready to tackle anything.” Rasmus Villumsen, the 22-year-old Greenlander who had accompanied them, was also in good shape.

Two days later, on November 1, the group gaily celebrated Wegener’s 50th birthday. Then, because supplies were short and Fritz Lowe had to stay to recuperate, Wegener and Rasmus Villumsen, the wind now at their backs, set off confidently for the coast. Their friends would never see them alive again. Wegener was found later in a grave which Villemsun had dug in the ice, but the body of Rasmus Villemsun was never found.

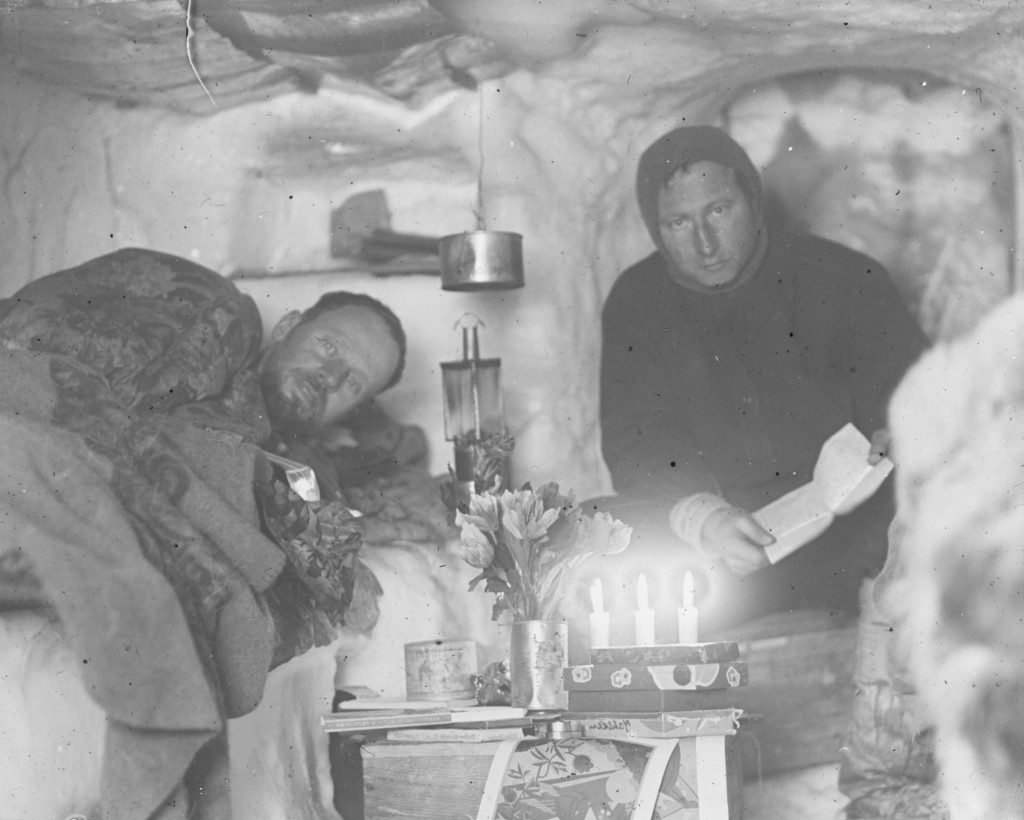

Overwintering at Eismitte – the three men at Eismitte spent most of the winter in their sleeping bags. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Last photo of Alfred Wegener and Rasmus Villemsun, taken on Wegener’s birthday, November 1 1930 at Eismitte, before they started their ill-fated return trip to the coast. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

The three men at Eismitte, by rationing the provisions, made them last until the arrival of a relief party. Fuel was so short that the three men at Eismitte had to spend most of the time in their sleeping bags. Fritz Loewe had his feet frost-bitten, and over the course of the winter his companions had to remove nine of his toes, one after the other, without dressings and without anesthetic, their only instrument being a pair of scissors and a pocketknife.

On May 7th, after the return of the sun, they were relieved by the arrival of the two aerosleds. These brought the desperately-needed stores, and took the sick Dr. Loewe and Dr. Sorge back to the coast with them. But Johannes Georgi chose to remain behind alone over the summer to continue making observations during the expeditions final months.

When Wegener, Lowe, and Villumsen failed to return, those at the base camp assumed they had decided to overwinter at Eismitte. When April came with no word, however, they sent out a search party in the two aerosleds to make sure. Some 118 miles inland the searchers came upon a pair of skis stuck upright in the snow, with a broken ski pole lying between them. They dug around, but found only an empty box. Puzzled, they went on to Eismitte, but when they heard Wegener and Villumsen had left six months before, they hurried back to make a more thorough search. On May 12, 1931, they found Wegener’s body. It was fully dressed and lying on a reindeer skin and sleeping bag stitched into two sleeping bag covers. Wegener’s eyes were open, and the expression on his face was calm and peaceful, almost smiling.

May 1931: Aerosled at Eismitte. In the right conditions, the Aerosleds proved their worth. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Aerosleds at Wegener’s grave – his body now lies under at least 300ft of ice and snow. Photo courtesy of Alfred Wegener Institute via Wikipedia

Apparently he died while lying in his tent. His friends thought Wegener probably suffered a heart attack brought on by the tremendous exertion of trying to keep up with the dogsled on skis over rough terrain. Rasmus Villumsen obviously buried Wegener with great care and respect, then presumably pressed on for the base camp, only to disappear into the white wilderness. Though a long, exhaustive search was made, the faithful Greenlander’s body was never found. Wegener’s friends left his body as they found it and built an ice-block mausoleum over it. Later they erected a 20-foot iron cross to mark the site. All have long since vanished beneath the snow, now 300 feet deep over his grave, inevitably to become part of the great glacier itself. It was a most fitting resting place for this remarkable man who devoted so much of his life to the study of that remnant of the last ice age and whose vision of moving continents provided the key to the mysteries of more ancient glacial epochs.

The expedition was by no means a failure. Careful observation and measurement validated the use of ice cores as precipitation – and hence climate – proxies. The thickness of the ice was measured using a combination of charges of dynamite and seismographs. It had been debated whether the ice was a cap on mountains or a sheet filling a valley. The expedition demonstrated conclusively that the Greenland ice sheet sits in a depression of its own making, the earth’s crust being pressed down by the overbearing weight of so much ice.

The two propeller-driven aerosleds were abandoned at the edge of the ice sheet when the expedition returned home in autumn 1931, although the engines were transported back to Germany. In 1932, Scheideck was visited again by Loewe and from a visit at this locality in 1934 photographs of the station, the surroundings and the propeller sledges were taken by J. Galster, the collection today being in the files of the Arctic Institute of Copenhagen. And again somewhat incidentally, the 1932 movie, SOS Eisberg, starring Leni Riefenstahl, was based on the story of this expedition.

In 1934, mountaineer H N Pallin visited West Greenland over the summer of 1936 on a mountaineering and glacier research expedition where he took photos of the remains of Wegener’s expedition, one of which included the remains of Wegener’s propeller-driven snowmobile.

Thirty years later, in 1965, M. Kogelbauer visited the area around Scheideck and found “Schneespatz” and “Eisbär” at the margin of the Inland Ice (Kogelbauer, 1965). The observations were also of glaciological interest since one of the aerosleds in 1965 stood on rock 6m above the ice surface while in autumn 1931 it had been left standing on a slab of rock level with the ice surface (Loewe, 1968).

However, abandoned and desolate on the edge of the Greenland Ice Cap as they were, the story of the Wegener Expedition’s Aerosleds was not yet over. In 1972 the director of the Danmarks Tekniske Museum, K. O. B. Jorgensen, applied to a mining company working in the area for help in salvaging and transporting of the sledges down from Scheideck. So it was that volunteers from Greenex and Danish Arctic Contractors (the firm running the installations at Sorge Engel) in the autumn 1973 collected and brought down the remnants of the sledges to Märmorilik harbour from where they were sent by boat to Copenhagen, arriving early November 1973. Dr. F. Loewe contributed by making contact between the engineer of the Wegener Expedition, C. Schif, and the Technical Museum so that Schif furnished the Museum with technical information on the sledges. Unfortunately only one of the sledges was reported as being in a condition where complete reconstruction is possible (and this was 40 years ago, in 1973).

Note: When I began researching this topic, I contacted the Danmarks Tekniske Museum (the Danish Museum of Science and Technolgy), who very kindly and promptly responded to me, confirming that they have pieces of the Wegener Propeller Sledge in their collection – the sledge was indeed excavated from the ice in 1973 and transported by ship to Copenhagen, after which the pieces were moved to the Museum at Elsinore. The pieces in the Museum consist of the skis, the engine console, footboards and a number of unidentified pieces. A restoration has been considered over the years but has not yet been decided on. In 1996, Antti Tervasmaa, the son of the Director of the Finnish Aircraft Factory, Arvo Tervasmaa, who had just written an autobiography of his life as a Finnair Captain, visited the Museum – the story of his quest in search of the remains of his father’s aerosleds is related below and based on an article he wrote which was published in the Aviation Society of Finland’s publication, Feeniks, in 1997.

The remains of the Propellor Sledge – from a Danish Newspaper article 1973. Photo courtesy of Danmarks Tekniske Museum (Danish Museum of Science and Technology)

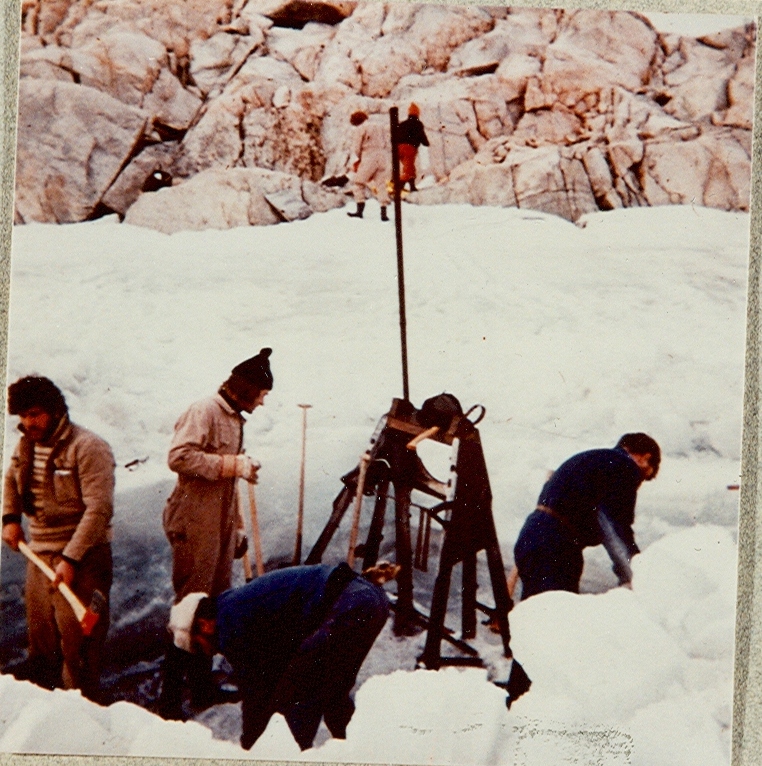

The Aerosleds being excavated from the ice, 1973. Photo courtesy of Danmarks Tekniske Museum (Danish Museum of Science and Technology)

Before the days of the Internet, knowledge of these Finnish-designed and built Aerosleds quickly faded into obscurity. The remains of one sled sat in the Danish Museum of Science and Technology for many years, but very few knew that these historic remnants were there. Just 15 years after the excavation of the Aerosled and its shipment to Copenhagen, in 1988, Finn Pedersen, the director of the museum in the small town of Uummannaq on Greenland’s west coast sent a letter to the Embassy of Finland in Copenhagen asked for help to determine the origins of some artifacts found nearby which had survived storms, snow, frost and ice over the years – the only clue as to the origins of these artifacts was a copper dog tag showing the swastika symbol of the Finnish Air Force and the text “Valtion lentokonetehdas Suomi Finland 14.3.30” (“State Aircraft Factory Finland Finland 03/14/30). Local memory of the snowmobiles had faded away in that short space of time.

The Finnish Embassy in Copenhagen was unable to supply an answer. Finnish museums and the archives of the State Aircraft Factory were examined but no clues were forthcoming. Apparently nobody involved in that early search for information recalled an article by the Finnish Air Force historian Colonel Janarmon in the Finnish aviation magazine Ilmailu, Issue N2 of 1963 (essentially this 1963 article is an obituary of Arvo Tervasmaa, with considerable information on the Wegener Aerosleds, of which much of the content is reproduced in this article). When Finn Pedersen’s inquiry arrived in 1988, Captain Antti Tervasmaa had recently retired and was living in Portugal. He heard about the inquiry a couple of years later and became interested. At the time, the only person still interested in the question was Kavo Laurila, who had followed up with various museums in Denmark and Greenland. As a result of his enquiries, Laurila had determined that the parts were from a snowmobile (aerosled). He learned that parts of one snowmobile, the skis, motor mount and the pilot’s console were in the Danish Technical Museum at Helsingor while other parts including axles were in the Uummannaq museum in Greenland. The origins and history of the snowmobiles however remained at that time obscure. It was known that they were used by the Wegener Expedition, but nobody knew who had designed and built them.

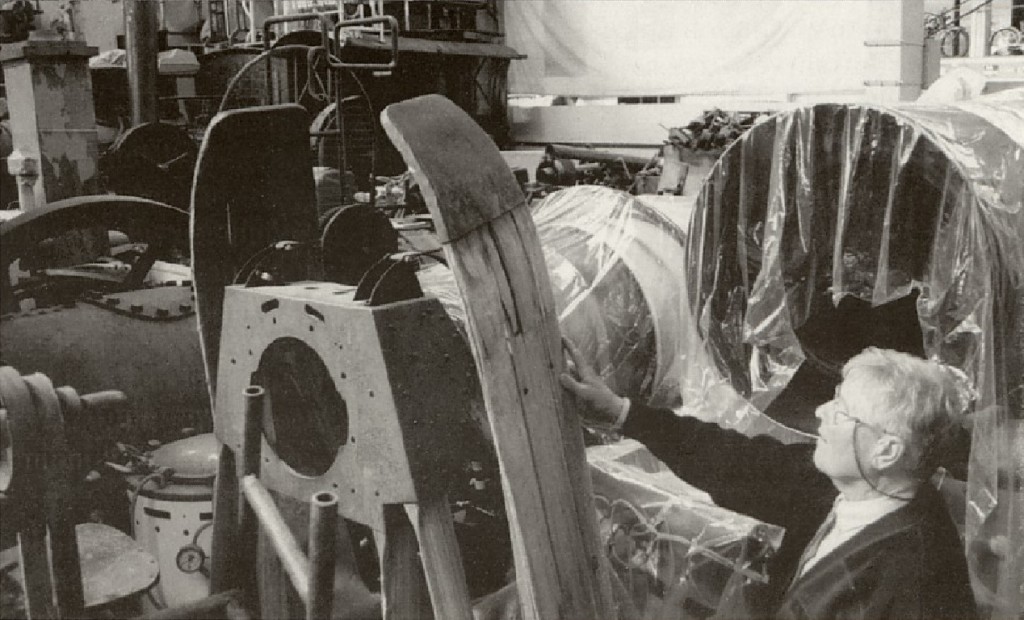

Captain Antti Tervasmaa was able to supply the missing link – the information that his father, Arvo Tervasmaa, had designed and built the Aerosleds for the Wegener Expeditions. Captain Tervasmaa also had in his possession a small number of photographs, one of which was a photo of himself, his older sister and his mother with a prototype of the Aerosleds built for the expedition. He also knew that his father’s design drawings for the snowmobiles had not survived the war – the family had been in the the Greater Vyborg area on the river near the sea, and from there had to urgently escape the advancing Russians. The drawings had been left behind and were never recovered. With his interest aroused, in the mid-1990’s, Captain Antti Tervasmaa set out to find traces of his father’s constructions and managed to track down the remains of both Aerosleds. With Kavo Laurila, he visited the remains of the Aerosled at the Danish Museum of Science and Technology (see photo immediately below). In the case of this Aerosled, only the skis, cabin console, axles and engine mounts together with other miscellaneous pieces remain.

Captain Antti Tervasmaa examines the remains of his father’s design at the Danish Museum of Science and Technology. Photo courtesy of Feeniks, the magazine of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society (http://www.imy.fi/)

In 1996, Captain Tervasmaa and Kavo Lauril flew to Greenland, first to Kangerlussuaq’issa (Sondre Stromfjord) and then on to a place called Ilulissat. For there they flew up the coast for an hour and a half to Uummannaq. The flight was rather indirect and twisted and turned with the coastline as VFR (Visual Flight Recognition) was the only flying possible. In Uummannaq, Captain Tervasmaa found that the small museum had a special section dedicated to the remains of the Wegener expedition, with the remains of the second snowmobile on display. Antti Tervasmaa returned to Finland with the satisfaction of having tracked down both his father’s Aerosleds and reliving childhood memories of his own trips in the Aerosleds. The first of the two photo’s below shows Antti Tervasmaa, son of the designer of the Aerosleds, with the remains of one of the Aerosleds at the Uummennaq Museum, Greenland in 1996. The second photo is a more recent photo of the remains of the sled at the Museum together with other artifacts from the Wegener expedition.

Antti Tervasmaa, son of the designer of the Aerosleds, with the remains of the second sled at th Ummennaq Museum, Greenland. Photo courtesy of Feeniks, the magazine of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society (http://www.imy.fi/)

In Uunnannaq in Greenland, you can see some remaining pieces of one of the motor sleds together with remains of at least 2 of Wegener’s haulage sleds. To the right is a fixture for the motor and airscrew, below the wreath is an axle with laminated ski, both from the propeller-sled.

And almost finally, film from the Wegener Expedition with a number of segments showing the Aerosleds. It’s silent film with no soundtrack, but the short clips showing the Aerosleds in motion gives you a very good idea of what they were capable of under the right conditions.

Tervasmaa’s Aerosleds and the Continuation War

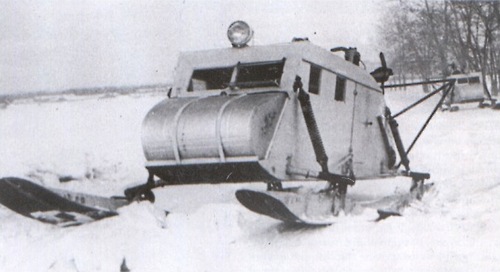

And finally, the photos of the Aerosleds used by the Wegener Expedition and Captain Antti Tervasmaa’s memories of his father’s work shine a new light on some of the aerosleds used by the Finnish military in WW2, the memory of which is preserved in a few hitherto obscure photos in the Finnish Defence Photo Archives, recently made available online. The aerosled in the photo below (with the von Rosen Cross used by the Finns, NOT the German swastika) seems to have been used as a transport model and is, as can be seen at a glance, virtually identical to the Aerosleds used by the Wegener Expedition.

The german caption for the above photo reads “Here’s another variant of the propeller sled used by the Finnish troops, whose military vehicles had the swastika as a national emblem. The bow shape suggests that this is a conversion of a Russian sled type NKL 16/41, used for the first time by the Russian side in the winter 1941/42 as transport snowmobiles.” In light of the Wegener Expedition photos, this is incorrect: this aerosled is very clearly the Tervasmaa design, only slightly different to the models used by the Wegener Expedition ten years previously. As well as the design of the Aerosled, the ski mount design would also support this interpretation.

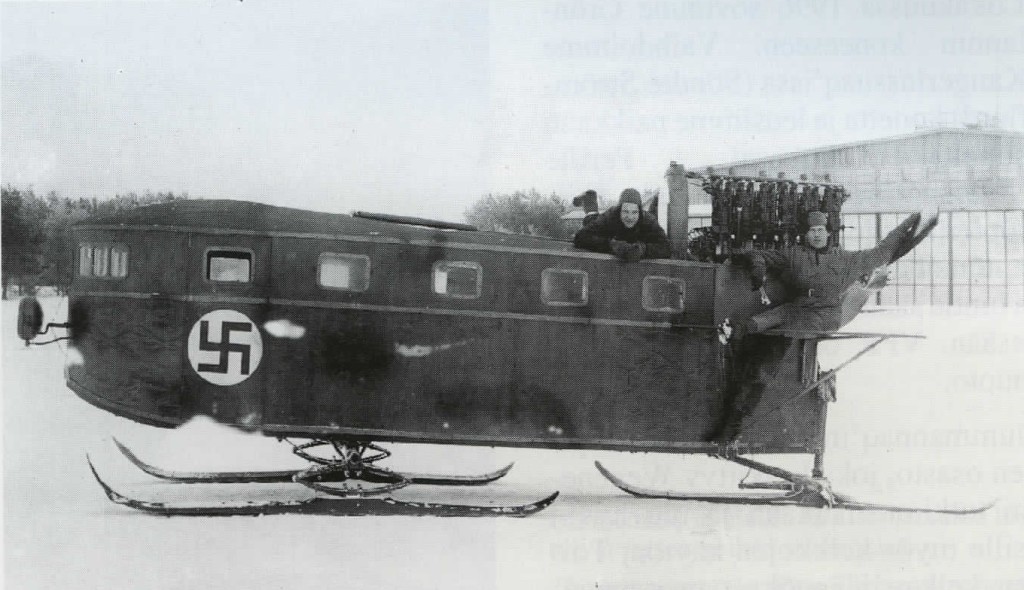

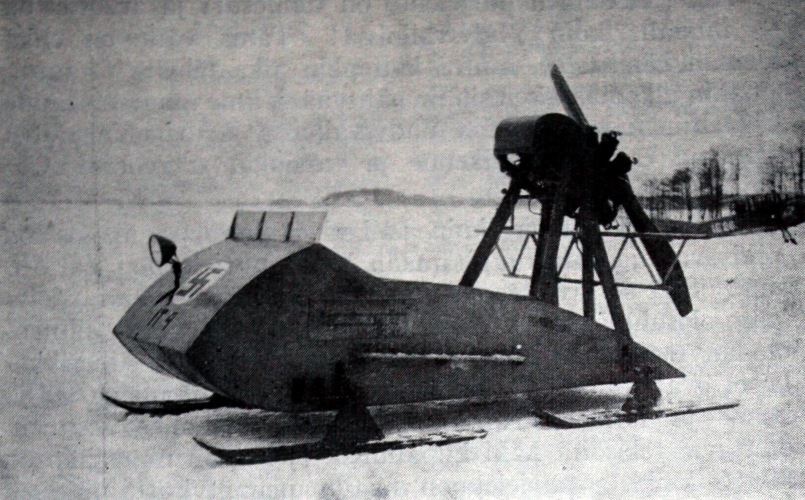

As can be seen in the photo on the right, the Soviet NKL 41/16 doesn’t look anything like the Finnish aerosleds. The skis are a completely different design, the supporting struts for the skis likewise, and the body shape is clearly different. Any resemblance is purely superficial and even to a casual observer, it’s easy to see the underlying design is completely different. And again in the photo below, this also seems to be the Tervasmaa design. Based on the limited photographic evidence, it does indeed seem that the Aerosled designed and built for the Wegener Expedition continued to be built by Valtion Lentokonetehdas for the Finnish military and were used well into the Continuation War, although none of these Finnish military models have survived to the present day.

The photo on the left is sourced from a 1983 French documentary about the Occupation of France, “La mémoire courte” (The Short Memory) and labels this aerosled as a Soviet Aerosani NKL 16/41. Clearly incorrect for anyone whose seen even a few photos of an NKL 16/41. The title of the documentary is indeed somewhat ironic in this instance as this is very clearly a Tervasmaa-designed and built Finnish aerosled. Also note the pintle with the machinegun mounted in the centre of the rear compartment as well as the Finnish ski mountings.

The engine would also appear to be the same Siemens engine as was used in the Wegener Expedition aerosleds – Finland had quite a supply of these engines dating back to a fairly large number purchased by the Air Force in the 1920’s. By the 1930’s, these engines were of no use for aircraft, but made a good source of propulsion for the aerosleds.

In this next photo, we get a good view from the rear of the same aerosled, “#2”. The machinegun on its pintle in the centre of the rear compartment is clearly visible, as is the Siemens rotary engine and again, the Finnish ski mounts. One suspects the troops in the rear compartment would be rather exposed and also subject to considerable noise from the close proximity of an aircraft engine within a few feet. In looking at these aerosleds, there is very little to distinguish them from the aerosleds built for the Wegener Expedition – again, the side windows, the entrance hatch to the rear compartment and the pintle for mounting the machinegun.

Following are a couple more photographs from the Finnish Defence Forces photographic archive. Immediately to the rear of the front Aerosled is another of the “Wegener” model aerosleds. From the caption associated with the photo, it is apparent that these aerosleds were to be used on Lake Onega over the winter of 1941/42. Again, the only real difference from the Wegener aerosleds is the slightly different shape of the side window and the hatch allowing entrance into the rear compartment.

The caption reads “Lento kelkkoja otetaan käyttöön Äänisellä. Kelkkoja puhdistetaan lumesta. Arsen-Navolok 1941.12.16” – Aerosleds will be introduced on Lake Onega. Cleaning the snow sleds. Arsen-Navolok 1941.12.16

The other two aerosleds in this photo pose an interesting question. They’re definitely not Soviet aerosans – being completely different from the Soviet aerosan models in use by the Soviet military. Although some of these were captured and reused by the Finns, these are a completely different design. In looking at the general design and bodyshape, they would appear to be armoured versions of the Tervasmaa design – the part of the ski mount visible in the photo is also a Finnish ski, albeit with reinforcing, no doubt due to the extra weight of the armour. The following photos, also of Finnish aerosleds that bear no resemblance to captured Soviet aerosan, would appear to support this conclusion.

This next photo on the right (below) shows the interior of the rear compartment in one of the armoured aerosleds. The machinegun pintle is clearly visible, as are small viewing ports in the sides and the riveted armour plate construction. And in the subsequent three photos we can see two different views of an armoured aerosled numbered “19”. Again, the basic shape is the same as the earlier Tervasmaa aerosleds, albeit made of armour plate cut and riveted to the basic body shape. On these models the engine is now protected by an armored casing with an armoured air intake. The skis are clearly the Tervasmaa ski design and the mounts for the skis are clearly the standard Finnish design as well.

While there don’t appear to be any published records available, it would appear that somewhere between the Winter War and 1941, a number of armoured aerosleds were constructed using the early Tervasmaa design as a starting point. Whether these armoured aerosleds were designed by Tervasmaa or simply modified from his earlier design is an open question. One would assume that for ease of construction, flat sheets of armour plate were used. From the photos, it would seem that the armour plate was riveted onto the aerosled frame rather than welded and the engines and air intakes were also armoured.

How many were constructed is open to question – the example in the photo to the right is numbered “13” while the aerosled in the photos below is numbered “19” so there must have been a few. That said, there is no published record of specialist Finnish aerosled units and apart from these few photos there is very little published information on Finnish aerosleds in military use during WW2 at all which leads one to surmise that they were not in widespread use. The photos here appear to be all that are included in the Finnish Defence Forces photo archives so even here, the evidence is very limited. The use made of these aerosleds in the Continuation War appears to have been limited to patrols on the ice of Lake Onega and perhaps Ladoga and the Gulf of Finland.

Arvo Tervasmaa himself would survive both the Winter War and the Continuation War. His aerosleds, in the development of which he played so decisive a role, were used heavily during the war, for winter traffic between Finland and Norway and for patrols along Finland’s borders. After finally resigning from the Air Force in 1946, he worked as Technical Director at the Kupio Ammunition Factory until 1949, when as was appointed Managing Director, a position he held until his retirement in 1956.

He was by nature modest, honest, direct and helpful. After the end of a long, stressful working day at the yard, or at the airport, he continued to work tirelessly in the domestic sphere, because he simply could not mess about and relax. The most skillfull wood and metal works and drawings were created in his hard working and talented hands. For his beloved daughters he even designed and cut dresses for many years.

After final retirement in 1956, he acquired a small plot and a cabin and withdrew to the peace of the countryside and his home district. Any thought that old age would bring rest proved far from the case. Work and hustle continued. He built and expanded his house and farm, so that it gradually became of the most highest standard, spacious and above all, a practical home and house design with rich fruit trees and other plantings. The latest technical novelties he installed were the central heating and an electric pump to draw water from the nearby lake. A few months before his death, his own “pump” gave him warning, but “as the timing didn’t disturb much his work plans” he submitted without protest to “a small full repair and rest period” in a hospital. After this, his life went on as usual. The end came suddenly. Arvo Tervasmaa passed away on 17 January 1963 as quietly and calmly as he had lived.

Sources:

In writing this article, I relied heavily on the sources listed below, in particular the article from Feeniks by Tervasmaa’s son, Captain Antti Tervasmaa, and the article from Ilmailu by Colonel Janarmon (both of which I translated from Finnish, with a bit of help – but if there are any mistakes in the translation and interpretation, blame it on my poor attempt at translating from the source) for information on Arvo Tervasmaa’s aerosleds. Some of the content of this article is a straight translation (more or less) from these articles, albeit restructured a little.

For information on the Wegener Expedition, I leaned heavily on Roger McCoy’s fascinating book, with its wealth of detail on Wegener, the expedition and the actual use of the aerosleds. The Danmarks Tekniske Museum was also incredibly helpful with information, as was the Aviation Museum Society of Finland who dug up the old articles for me, scanned them in and made them available to me by email – a tremendous piece of assistance for which I am very grateful. I’d also like to thank Juha-Pekka for help with translations, Seppo Koivisto for his help, translating when I got stuck, and pointing me to source material I would otherwise have been completely unaware of – and last but by no means least, thx Juha for all the photos you dug up!

Mitteilungen – Final Destination of “Schneespatz” and “Eisbär” – the Propeller Sledges of Wegener’s Last Greenland Expedition By Anker Weidiek (http://epic.awi.de/28030/1/Polarforsch1974_1_12.pdf)

Article by Captain Antti Tervasmaa from Feeniks N2, 1997 courtesy of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society

Article by Colonel Janarmon in the Finnish aviation magazine Ilmailu, Issue N2 of 1963 courtesy of the Finnish Aviation Museum Society

Photos and information on the Aerosled remains in the Danmarks Tekniske Museum supplied to the author by the Danmarks Tekniske Museum (Danish Museum of Science and Technology)

Information and photos of the Wegener Expedition from the Alfred Wegener Institute

Antti Tervasmaa’s autobiography, “The Life and Times of an Ordinary Captain”, published by FinPro Inc., Michigan, USA

Roger McCoy’s “Ending in Ice: The Revolutionary Idea and Tragic Expedition of Alfred Wegener”, Oxford University Press, 2006

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2014 Alternative Finland