The Boer Volunteers of the De La Rey Battalion formed an oddball unit from within the British Commonwealth, but it was a unit which refused point-blank to fight alongside any of the British units or under any British officers or British Commonwealth commanders at any level. This was the De La Rey Battalion, a unit of South African Boer volunteers who were all members of the Ossewabrandwag. The Ossewabrandwag had started out as an organisation dedicated to the preservation of Afrikaans culture but had rapidly evolved into a highly motivated politically militant organisation, with a membership in the hundreds of thousands.

The Ossebrandwag was strongly anti-communist and this, together with their seeing many parallels to their own situation at the hands of the British in the plight of Finland let to the dispatch of a sizable volunteer contingent to fight for Finland.

The Boer militants of the Ossebrandwag were hostile to Britain, opposed South African participation in WW2, even after the Union of South Africa declared war in support of Britain in September 1939 – but they were strongly sympathetic to Finland, seeing many parallels to their own situation (where the Republiek van Transvaal and the Oranje Vrijstaat had been attacked, conquored and annexed to South Africa by the British) in the attack on Finland by the USSR. Staunchly religious, the Boerevolke had much in common with the congregations of more conservative Lutheran churches in Finland such as the Pietists and were strongly anti-communist.

Not only did they have much in common, there were also long-standing ties between Finland and the Boers – ties that had faded a little from popular memory in both countries by the late 1930’s but which were rapidly resurrected in South Africa at least, and most strongly by the Ossebrandwag. These ties went back to the 1899-1902 Boer War (in Afrikaans, die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, the “Second War for Freedom.” The official term in the Afrikaner historiography for the wars against the British Empire in 1880-1881 and 1899-1901 were the First and Second Wars for Freedom).

Eighty-five odd years ago, on December 11th, 1924, the Republic of Finland celebrated a very special anniversary – the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Magersfontein, part of the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902. The state and the military establishment hosted this anniversary at the Officers’ Casino Building in the Katajanokka neighborhood of Helsinki and among the guests of honour were Lauri Malmberg, the minister of defense, and Per Zilliacus, the chief of staff of the Civil Guard. The Suojeluskuntas (Finnish Civil Guard) also sent a wreath tied with blue-white ribbons to South Africa, where it was laid at the monument on the battlefield of Magersfontein. (the Battle of Magersfontein was the second of the three battles fought over the “Black Week” of the Second Boer War. It was fought on 11 December 1899 at Magersfontein near Kimberley on the borders of the Cape Colony and the independent republic of the Orange Free State. General Piet Cronje and General De la Rey’s Boer troops defeated British troops under the command of Lieutenant General Lord Methuen, who had been sent to relieve the Siege of Kimberley).

The conservative Finnish newspaper “Uusi Suomi” (New Finland) advertised the event on its front page, and the periodicals of the Suojeluskuntas published anniversary articles on the conflict between the Boer republics and the British Empire. The celebration opened with the Finnish Naval Orchestra’s performance of “Kent gij dat volk,” the South African anthem.

“Kent gij dat volk” – the National Anthem of The Transvaal

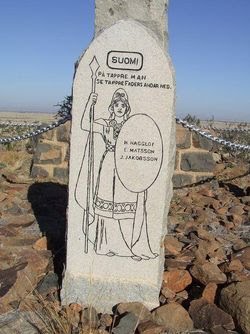

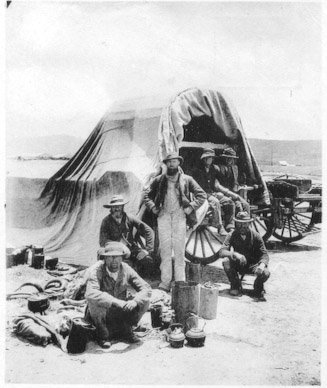

The reason that independent Finland in 1924 celebrated a battle fought in a British colonial conflict in South Africa a mere 25 years previously was straightforward. Finnish volunteers had fought in the battle as soldiers of the Scandinavian Corps of the Boer forces. The Scandinavian Corps was founded in Pretoria on September 23rd, 1899, supposedly as a testimony of loyalty felt by the Scandinavian immigrants towards the South African Republic. It included 118 men; 48 Swedes, 24 Danes, 19 Finns, 13 Norwegians and 14 other miscellaneous nationalities, mainly Germans and Dutch. In addition, three Swedish women served as nurses in a separate ambulance unit. The Scandinavians fought in the siege of Mafeking and in the battles of Magersfontein and Paardeberg; of these battles, Magersfontein was the most significant.

Those Finns who volunteered to fight in the Boer forces were, of course, immigrants to the Transvaal, people who had come to the gold fields of Witwatersrand in search of wealth and a better life. Some had arrived directly from Finland, others came via the United States. The uptick in immigration to the Transvaal had been one of the causes of the war, and the British guest-workers and settlers — the so-called “uitlanders” — formed a fifth column through which the British Empire sought to strengthen its grip over the Boer republic. As a political and military strategy, the British attempt to control the Transvaal via migration failed utterly. After the outbreak of the war, most of the British immigrants were either deported or decided to leave on their own, rather than fight the Boer governments. Worse yet (from London’s perspective), the non-British immigrants — Germans, Dutch, Italians, Irish, Russians, and obviously Scandinavians, including Finns — decided to stay and support the Boer war effort.

There is a further irony in the fact that most of the Finns in South Africa were Swedish-speaking, from coastal Ostrobothnia. This was an era of bitter language strife in Finland, when the rural Swedish population sought to present itself as a separate ethnic group of “Finland Swedes.” Nevertheless, the Finnish immigrants to South Africa identified closely with their former homeland, and set up a separate Finnish platoon rather than merging with the Swedish nationals who made up the majority of the Scandinavian Corps. Of the eighteen men who served in the Finnish platoon, only three spoke Finnish as their first language, but it appears that all of them regarded themselves as Finns. Matts Gustafsson, one of the volunteers who wrote poems, later noted, “Och wi voro finnar hwarendaste man,” which translates as, “And we were Finns, every single man.”

Although there was a lot of sympathy for the Boer cause outside of the British Commonwealth, there was little overt government support as few countries were willing to upset Britain, in fact no other government actively supported the Boer cause. There were, however, individuals who came from several countries as volunteers and who formed Foreign Volunteer Units. These volunteers primarily came from Europe, particularly Germany, Ireland, France, Holland and Poland. In the early stages of the war the majority of the foreign volunteers were obliged to join a Boer commando. Later they formed their own foreign legions with a high degree of independence, including the: Scandinavian Corps, Italian Legion, two Irish Brigades, German Corps, Dutch Corps, Legion of France, American Scouts and Russian Scouts. While the vast majority of people involved from British Empire countries fought with the British Army, a few Australians fought on the Boer side as did a number of Irish, the most famous of these being Colonel Arthur Lynch, formerly of Ballarat, who raised the Second Irish Brigade. Lynch, charged with treason was sentenced to death, by the British, for his service with the Boers. After mass petitioning and intervention by King Edward VII he was released a year later and pardoned in 1907. However the free rein given to the foreign legions was eventually curtailed after Villebois-Mareuil and his small band of Frenchmen met with disaster at Boshof, and thereafter all the foreigners were placed under the direct command of General De la Rey.

After the war, a special Scandinavian monument was constructed on the battlefield of Magersfontein. The monument consisted of four cornerstones, representing the four Nordic countries, each decorated with the Scandinavian valkyrie and national symbols of each country. The verse on the monument is from Johan Ludvig Runeberg’s March of the Pori Regiment, these days the official Finnish presidential march: “On valiant men the faces of their fathers smile.” The names of the fallen soldiers are engraved on the shield. Emil Mattsson died at Magersfontein; he was buried on the battlefield. The British captured Henrik Hägglöf, who died from his wounds at an infirmary near the Orange River. Johan Jakob Johansson — whose name is mistakenly written “Jakobsson” — died at the British prison camp on St. Helena and is buried in grave number 18 at the Knollcombe cemetery on the island. The name of Matts Laggnäs, another Finnish volunteer who died in captivity on St. Helena, is missing.

The foreign volunteers who fought with the Boer forces — John MacBride perhaps being the most famous example — utilized their talents in later conflicts in their own homelands. The “flying columns” invented by the Boer commandos became a standard tactic in the Irish Republican Army. In Finland, the Boers served as an example to both the Civil Guards, who formed the White forces in the Civil War of 1918, and their Red Guard opponents. Lennart Lindgren, the commander of the Oulu Red Guard in 1918, was a veteran of the Boer War, and even Väinö Linna’s “Under the North Star” — something of a modern national epic in Finland, and recently made into a movie for the second time — includes a reference to Finnish Red Guardsmen “reminiscing about the stories of the Boers, which they had heard from their parents as small boys.”

What was the significance of the Finnish Republic’s 1924 commemoration of its citizens’ participation in the Boer War? Perhaps most importantly to Finland, the Boer resistance against the British Empire set an example for national movements of the time and this explains the Finnish fascination with the Boers. At the time of the war, the Grand-Duchy of Finland had become a target of Russian imperial reaction. The February Manifesto of 1899 began a Russian attempt to abrogate Finnish autonomous institutions and integrate it into the Russian Empire. The Boer resistance to Britain aroused sympathy in beleaguered Finland, and the participation of the Finnish volunteers in the battle on the Boer side became a source of pride. Arvid Neovius, one of the organizers of the underground opposition to Russia, wrote an article where he spoke of the “intellectual guerrilla warfare” and argued for modelling Finnish passive resistance to Russia on Boer hit-and-run-tactics. The South African national anthem became a popular protest song that eventually found its way into Finnish schoolbooks. Finnish participation in another country’s war of national liberation was thus very much alive and supportive of the Afrikaner “liberation struggle” in 1924, only seven years after Finland gained its independence.

Finnish author Antero Manninen later described the view of the Boer War with the following words: “Over forty years ago, as the 19th century was drawing to a close, two small nations became targets of unjustified pressure and attack by their greater and more powerful neighbors. One of these was our own nation, whose special political status was singled out for elimination in the so-called February Manifesto; the other one were the Boers, living on the other side of the globe. This common experience between our nations was the reason why the people of Finland, like the entire civilized world, followed the Boers and their struggle for independence with special sympathy, and rejoiced for the successes they gained in the early stages of the war.” The situation was paradoxical, because Russian popular opinion in 1899-1902 was also very sympathetic towards the Boers. Consequently, the Russian press could write with official state endorsement articles espousing a pro-Boer and anti-British postion …. while at the same time, the Russian Governor-General would censor similar articles in Finnish newspapers.

During the inter-war era, the memory of the Boer War was invoked in Finland on many occasions. As mentioned, the old Transvall national anthem, “Kent gij dat volk” was translated in Finnish and included in elementary school songbooks. The festivities of 1924 were followed by a Scandinavian shooting contest named “In Memory of Magersfontein” in Helsinki in the summer of 1925. A Finnish encyclopedia from 1938 contains a page-length article on the Finnish volunteers in South Africa, as a prologue to the history of the Finnish independence struggle. It was definitely considered an important historical event. The memory of the Boer War was also used in domestic Finnish political rhetoric. Perhaps the most famous example is Juho Kusti Paasikivi, who was the chairman of the conservative National Coalition party in the 1930s, and became the President of the Republic after WW2. At the height of the extreme right-wing reaction and the activities of the Lapua movement, Paasikivi sought to actively distance the right-wing conservatives from the extremist elements and established himself as the right-wing champion of parliamentary democracy. On June 21st 1936 he travelled to the town of Lapua in Ostrobothnia, to the very cradle of Finnish right-wing extremism, and gave a speech entitled “Freedom”, in which he defended parliamentary democracy and civil liberties, urging the locals to abandon extreme right-wing radicalism. As a historical example to be followed, he invoked the memory of South Africa, and made a reference to a speech where Jan Smuts had also defended parliamentary form of government: “As I was thinking of my presentation, I re-read one speech, made two years ago by a freedom fighter who, even though he lives and operates far away from our country, is a Western man by his opinions and character – the leading general and statesman of the Boer nation in South Africa, his name is Jan Smuts. As we all know, those Boer farmers, who served their God and fought for their freedom far away in the southern lands, share the same mentality as the people of Ostrobothnia…” The Union of South Africa was thus invoked as a model of democracy by the inter-war Finnish champions of democracy.

Finnish views were not however wholly one-sided in support of the Boers. At the time of the Boer War, the Finnish press did express some criticism towards the Boers. The one newspaper which stood out was the venerable Conservative-Fennoman Uusi Suometar (“New Finlandia” – , Suometar translates as the feminine embodiment of Finland), at the time the leading national newspaper with the widest circulation. Already during the autumn of 1899, Uusi Suometar adopted a critical tone towards President Krüger’s confrontational policy, and criticized the government of the Transvaal for a lack of realism. As far as is known, they were also the only Finnish newspaper which criticized the Boer actions towards the native African peoples in any way. The newspaper also expressed understanding for British interests, attempted to portray the war in a “fair and balanced” fashion, and expressed a hope that Britain would be willing to grant tolerable peace terms to the Boer republics. This position was essentially a reflection of those same arguments which the newspaper advanced with regard to the question of Finnish autonomy and relations with Russia. As a conservative paper, the newspaper advocated Finnish acquiescence and compliance towards Russian imperial interests, in order to avoid excessive imperial reaction; while at the same time, they were also reluctant to criticize Britain, because they considered British goodwill and sympathy important in the international campaign for Finnish autonomy.

(For details on the internation campaign on behalf of Finland, you may check the address “Pro Finlandia”, signed among others by Florence Nightingale, Émile Zola and Anatole France. The year 1899 was an important year for many small nations, and Finland was a small cause célèbre for European intellectuals for a short period). Uusi Suometar was the largest newspaper, but it was probably an exception in its moderate approach to the conflict. Other Finnish newspapers were rather more openly pro-Boer. The constitutional Päivälehti (“Daily Newspaper”, a direct predecessor of today’s Helsingin Sanomat, “Helsinki News”) was very pro-Boer, although they also remembered to mention hat Britain should be considered as the “supporter and guardian of Finland in Europe”. Not surprisingly, this newspaper was also the favourite target of Russian censorship. The socialist Työmies (“Worker”), which was censored by both the Russian and Finnish authorities, was overtly pro-Boer, and regarded the conflict as an imperialist war initiated by the British capitalists. Swedish-language Finnish newspapers were in a class of their own, because they were the only ones which mentioned the race factor openly. Nya Pressen, which advocated constitutional resistance towards Russia, condemned the British actions in South Africa precisely because of their nature as actions against another white nation. The newspaper made it specifically clear that they wholeheartedly approved colonial rule over “inferior” people, but the Boers were “representatives of European culture”. This was a clear reflection of the newspaper’s own view of the Swedish-speaking minority in Finland as the “bulwark of Scandinavian civilization” standing against the Russian influence.

The other Scandinavian newspapers were equally divided in their opinions. The conservative Svenska Dagbladet was pro-British, but the liberal and social democratic Swedish newspapers were pro-Boer. The Norwegian Aftonbladet and Verdens Gang were pro-Boer, but also tried to avoid excessive criticism of Britain. The Norwegian reasons for this moderation were somewhat similar to Finnish motives; they were reluctant to jeopardize British support for Norway at a time when the termination of the union with Sweden was becoming topical. In their views, the Finnish newspapers were more or less part of the Scandinavian mainstream in their opinions and in their differences of opinion. The Russian opinion, however, was adamantly and absolutely pro-Boer and anti-British all across the political spectrum, from Tolstoy all the way to Lenin. As the war continued, even Uusi Suometar gradually adopted a more pro-Boer stance. The decisive factor in this change of opinion were the British actions towards the end of the war, the scorched-earth tactics and the concentration camps, which aroused absolute horror even in Finland. The large scale deaths of Boer women and children in the British concentration camps evoked protests world-wide, as did the conditions in the island prisons of Ceylon and St. Helena, the latter of which housed Finnish prisoners for nineteen long months. The reason was simple. The British Empire was regarded as a liberal, responsible and humane great power, and if they could resort to such methods, what was going to prevent the other, more callous great powers from taking equally harsh actions with other small nations? Because of the Russian censorship, the Finnish newspapers could not openly mention that the British actions had ignited their fear of Russia, but the message was clear from between the lines.

In 1924, these memories were still vivid in the minds of many Finns. The young people who lived in the inter-war era sang the Finnish translation of “Kent gij dat volk” in schools while in Church they would light a candle and recite the words “De God onzer voorvaden heeft ons heden een schitterende overwinning gegeven.” Even after the successful gaining of independance from Russia, the clash between a few amateur Finnish riflemen and the elite Scottish soldiers of the British Army continued to hold a national symbolic importance in Fimland.

South Africa and the Winter War

By 1925, Finnish diplomatic representation in South Africa consisted of honorary consulates in five South African cities – Cape Town, Johannesburg, Durban, Port Elizabeth and East London. The duties of the honorary consuls involved mainly trade and maritime affairs. Finnish nationals were preferred for the posts but when they were unavailable, Scandinavian nationals were somewhat reluctantly appointed. The Finnish foreign ministry held (understandably) suspicions that Scandinavians might promote exports from their home country rather than Finnish exports. The Great Depression of the 1930’s forces the intensification of cooperation between the Finnish foreign ministry and Finnish exporters in the search for new markets and South Africa became one of the targets. From 1925 to 1939 exports to South Africa averages 1.45% pf the total value of Finnish exports annually. Although the figure is small, South Africa was a large market for Finnish sawn timber and was the number one source of imported timber for South Africa, ahead of both Canada and Sweden. Many of the Finnish firms which later achieved prominent positions in South African markets established their trading relationships at this time. Wool, tannic acids and fruits were in turn the top South African exports to Finland. However, even with the growing trade between the two countries it was not until 1937 that a Finnish consulate in Pretoria was actually established.

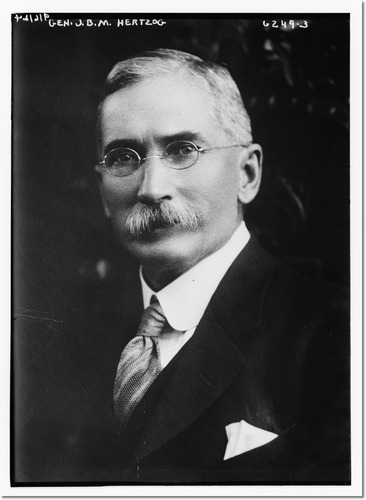

When the USSR attacked Finland on 30 November 1939, the reaction in South Africa was as strongly pro-Finnish as in almost all other countries worldwide. As the Finns had sympathized with the Afrikaners on the Boer War, so the South Africans were supportive of Finland. South Africa donated 25 aircraft (Gloster Gauntlets that South Africa had purchased but which were still in the UK) and public donations of 27,000 pounds were raised within days. In an additional gesture of goodwill, South African wine growers donated 24,000 litres of brandy. Initially, the South African Government had decided little more could be done to assist Finland – there were greater concerns within the country as, as on the eve of World War II, the Union of South Africa found itself in a unique political and military quandary. While it was closely allied with Great Britain, being a co-equal Dominion under the 1931 Statute of Westminster with its head of state being the British King, the South African Prime Minister on September 1, 1939 was J.B.M. Hertzog – the leader of the pro-Afrikaner and anti-British National Party. The National Party had joined in a unity government with the pro-British South African Party of Jan Smuts in 1934 as the United Party.

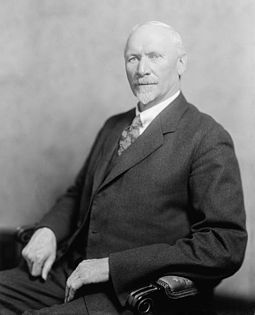

James Barry Munnik Hertzog, better known as Barry Hertzog or J. B. M. Hertzog (3 April 1866 near Wellington, Cape Colony – 21 November 1942 in Pretoria, Union of South Africa) was a Boer general during the second Anglo-Boer War who later went on to become Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1924 to 1939. Throughout his life he encouraged the development of the Afrikaner culture, determined to protect the Afrikaner from British influence.

Hertzog’s problem was that South Africa was constitutionally obligated to support Great Britain against Nazi Germany. The Polish-British Common Defence Pact obligated Britain, and in turn Britain’s Dominions, to help Poland if it was attacked by the Nazis. After Hitler’s forces attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, Britain declared war on Germany two days later. A short but furious debate unfolded in South Africa, and particularly in the South African Parliament, pitting those who sought to enter the war on Britain’s side, led by an Smuts, against those who wanted to keep South Africa neutral, if not pro-Axis, led by Hertzog. In this view, Herzog was reflecting the majority Afrikaner viewpoint – and he was also acutely conscious of the political threat to the National Party by the “Purified National Party” of D. F. Malan, which had broken away from the National Party when the latter merged with Smuts’ South African Party in 1934 and which was by this time perhaps the chief vehicle of Afrikaner nationalism. On September 4, the United Party caucus refused to accept Hertzog’s stance of neutrality in World War II and deposed him in favor of Smuts. Hertzog himself, together with a number of supporters, left the United Party and merged with Dr D.F. Malan’s National Party in a party called the Herenigde (Reconstituted) National Party under Hertzog’s leadership. But while Malan supported Hertzog with enthusiasm, the more radical nationalists in the north constantly undermined him. Hertzog’s real commitment was to a form of democracy that was modeled on that of the old Boer republics and after a showdown at a party congress Hertzog withdrew from the party and Malan became leader in 1940. Hertzog himself was now a disillusioned and embittered man but even so, he discouraged militant action against the war effort. To future entrepreneur Anton Rupert and some other Afrikaner students who privately asked his advice about militant resistance, he suggested they return to their studies. The Afrikaners would take over after the war by way of the ballot booth, he assured them. Hertzog died in 1942.

Upon becoming Prime Minister, Smuts declared South Africa officially at war with Germany and the Axis. He immediately set about fortifying South Africa against any possible German sea invasion because of South Africa’s global strategic importance controlling the long sea route around the Cape of Good Hope. Smuts was also invited to join the Imperial War Cabinet in 1939 and in May 1941 was appointed a Field Marshal of the British Army, becoming the first South African to hold that rank. The Afrikaner Ossewabrandwag movement and other Afrikaners strongly objected to South Africa’s participation in World War II and ultimately, Smuts would pay a steep political price for his support for the War, his closeness to the British establishment, to the King, and to Churchill. All of these would combine to make Smuts highly unpopular amongst the Afrikaners, leading to his eventual downfall in the immediate aftermath of WW2.

General Jan Christiaan Smuts (24 May 1870 – 11 September 1950) was a prominent South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various cabinet posts, he served as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa from 1919 until 1924 and from 1939 until 1948. He served in the First World War and as a British Field Marshal in WW2.. He led Boer commandos in the Second Boer War, fighting for the Transvaal. During the First World War, he led the armies of South Africa against Germany, capturing German South-West Africa and commanding the British Army in East Africa. From 1917 to 1919, he was also one of five members of the British War Cabinet, helping to create the Royal Air Force. He was the only person to sign the peace treaties ending both the First and Second World Wars. At home, his preoccupation with the war had severe political repercussions in South Africa. Smuts’s support of the war made him unpopular amongst the Afrikaners and this together with D F Malan’s pro-Apartheid stance won the Reunited National Party the 1948 general election. Smuts, who had been confident of victory, lost his own seat in the House of Assembly and retired from politics.

In late 1939, the South African population consisted of two million whites of which there were about 250,000 men in the military age group of 18 to 44. At the time of the declaration of war against Germany in September 1939, the South African Army Permanent Force (PF) numbered only 3,353 regulars, with an additional 14,631 men in the Active Citizen Force (ACF) which gave peace time training to volunteers and in time of war would form the main body of the army. The commando units had a strength on paper, of about 122,000 men, but of these only about 18 000 men were properly armed and many of these were not properly trained. Furthermore, it had to be borne in mind that not all PF, ACF or Commando members were in favour of the Union’s participation in the war. The declaration of war on Germany had the support of only a narrow majority in the South African parliament and was far from universally popular. Indeed, there was a significant minority actively opposed to the war and under these conditions conscription was never an option and thus the expansion of the army and its deployment overseas depended entirely on volunteers. In addition, pre-war plans did not anticipate that the army would fight outside Southern Africa and it was trained and equipped only for bush warfare.

In the view of the Government, all of this precluded any substantial assistance to Finland beyond what had already been extended. South Africa simply did not have the industrial capacity to offer any meaningful assistance to Finland.

In this however, the Ossewabrandwag (the “Ox Wagon Sentinels”) begged to differ. As has been mentioned, the Ossewabrandwag was a highly motivated and politically militant organisation dedicated to gaining power for the Afrikaners and to the preservation of Afrikaans culture. In 1939, when the white population of South Africa numbered some two million, of which around half were Afrikaners, the membership of the Ossewabrandwag numbered around one hundred thousand. And the Ossewabrandwag were not only politically militant. Members of the Ossewabrandwag refused to enlist in the South African forces, and sometimes harassed servicemen in uniform. They also formed a paramilitary wing, the Stormjaers (Assault Troops), one of whose “generals” was the future South African Prime Minister, Balthazar Johannes Vorster (December 1915 – 10 September 1983),

In December 1939, the news that South Africa’s traditional foes on the Rugby field were sending a Battalion of Volunteers made headline news in South Africa. Within Afrikaner political circles, a fierce debate raged. The assistance given by the small number of Finns to the Boer Commandoes in die Tweede Vryheidsoorlog was raised, as was Finnish support in the war that in 1939 was well within living memory. Within the Ossewabrandwag, the debate centered on whether Boer volunteers should go to Finland, and if so could this be seen as assisting Britain in any way. Vorster himself, one of the young firebrands of the Stormjaers, was firmly of the opinion that a Boer Volunteer force could and should assist Finland and that this should be done regardless of Britain’s actions. The actions of the Finnish volunteers in fighting for the Boer Republics was a debt that should be repaid, Vorster repeated in speech after speech, and in this he and his mentor, Johannes Frederik Janse ‘Hans’ van Rensburg, who was in complete agreement on this point, carried the day.

Over January 1940, the Ossebrandwag organised a group of some 1,100 volunteers, almost all of whom were already members of the Stormjaers (the paramilitary wing of the OB). After heated negotiations (conducted by Hertzog on behalf of the OB) with the government of Jan Smuts, whom the members of the Ossebrandwag regarded as a traitor to the Afrikaaner cause, it was agreed that the South African government would provide a ship to transport the volunteers to Finland together with individual military equipment (uniforms, webbing, basic kit, Rifles, machineguns and ammunition). Many of the Boer volunteers had limited military experience from the Commandoes, enough had military training that they could provide sufficient officers and men for the unit, and almost all had grown up on the veld, shooting since they were old enough to stand up unaided. As with their fathers and grandfathers from the Boer War, many were crack shots and all were used to living rough. They were tough men, used to an outdoor lifestyle, used to living rough and not afraid of a good fight. By popular acclaim, they named their unit the De La Rey Battalion, after the Boer Was hero, General Koos de la Rey. The nature of the Stormjaers of the De La Rey Battalion was evidenced by the oath sworn by the volunteers as they signed on to fight for Finland: “As ek omdraai, skiet my. As ek val, wreek my. As ek storm, volg my” (“If I retreat, kill me. If I die, avenge me. If I advance, follow me”).

Op ‘n berg in die nag lê ons in die donker en wag

in die modder en bloed lê ek koud,streepsak en reën kleef teen my

en my huis en my plaas tot kole verbrand sodat hulle ons kan vang,

maar daai vlamme en vuur brand nou diep, diep binne my.

On a mountain in the night, we lie in the darkness and wait

In the mud and blood I lie cold, grain bag and rain cling to me

My house and my farm burnt to ashes, so they they could capture us

But those flames and that fire burn now deep deep within me.

De La Rey, De La Rey sal jy die Boere kom lei?

De La Rey, De La Rey

Generaal, generaal soos een man, sal ons om jou val.

Generaal De La Rey.

De La Rey, De La Rey will you come to lead the Boer?

De La Rey, De La Rey

General, General as one man, we’ll fall in around you.

General De La Rey.

Oor die Kakies wat lag,’n handjie van ons teen ‘n hele groot mag

en die kranse lê hier teen ons rug,hulle dink dis verby.

Maar die hart van ‘n Boer lê dieper en wyer, hulle gaan dit nog sien.

Op ‘n perd kom hy aan, die Leeu van die Wes Transvaal.

And the Khakis that laugh, just a handful of us against their great might

With the cliffs to our backs, they think its all over for us

But the heart of a Boer lies deeper and wider, that they’ll still find out

At a gallop he comes, the Lion of the West Transvaal

De La Rey, De La Rey sal jy die Boere kom lei?

De La Rey, De La Rey

Generaal, generaal soos een man, sal ons om jou val.

Generaal De La Rey.

De La Rey, De La Rey will you come to lead the Boer?

De La Rey, De La Rey

General, General as one man, we’ll fall in around you.

General De La Rey.

Want my vrou en my kind lê in ‘n kamp en vergaan,

en die Kakies se murg loop oor ‘n nasie wat weer op sal staan.

Because my wife and my child lie in a Hell-camp and perish,

And the Khakis vengeance is poured over a nation that will rise again

De La Rey, De La Rey sal jy die Boere kom lei?

De La Rey, De La Rey

Generaal, generaal soos een man, sal ons om jou val.

Generaal De La Rey.

De La Rey, De La Rey will you come to lead the Boer?

De La Rey, De La Rey

General, General as one man, we’ll fall in around you.

General De La Rey.

The Boer Volunteers, mostly men from the Northern Transvaal and from the Orange Free State, gathered outside Cape Town over the month of January 1940, trickling into the Camp in small groups. By late January 9104 some 1,100 volunteers had gathered, almost all with at least some form of training from the Commandoes and all undergoing basic military training under the instruction of those with prior military experience or training. NCO’s and Officers had been selected, largely following the old Boer tradition of the men selecting their own leaders. The Commando CO was selected in the same way, with 24 year old Ossewabrandwag Stormjaer “General”, Balthazar Johannes Vorster (who would go on to become Prime Minister of South Africa in 1966) being elected as the commanding officer. The Union Defence Force provided the volunteers with individual military equipment (uniforms, webbing, basic kit, Rifles and rifle ammunition) and machineguns and mortars for training but little else.

The Commando was the basic unit of organisation of the Boer militia with the term coming into English usage during the Second Boer War. The Commando system had its origins as early as 1658, when fighting had erupted between the Dutch settlers of the Cape Colony and the local Khoi-khoi tribes. In order to protect the settlement, all able bodied men were called up to fight and at the conclusion of this war, it was decided that all men in the colony should be liable for military service if needed – and all were expected to be ready on short notice. By 1700, the size of the colony had increased hugely in geographical size and the small military garrison at Cape Town couldn’t be counted on to react swiftly in the distant border districts. It was at this time that the commandosystem was expanded and formalized. Each district had a Kommandant who was charged with calling up all burghers in times of need. In 1795, with the First British Occupation and again in 1806 with the Second British Occupation, the commandos were called up to defend the Cape Colony. At the Battle of Blaauwberg (6 January 1806), the Swellendam Commando held the British forces off long enough for the rest of the Cape Colony army to retreat to safety.

At the time of the Great Trek, the commando system was still in existence and was institutionalized by both the Boer republics – the Transvaal and the Orange Free State as well as by the short-lived Natalia Republic. The Great Trek itself is a central part of the Afrikaner culture and history – some 12,000 Voortrekkers (literally “those who trek ahead”) left the British-governed Cape Colony and trekked east and north-eastward into Africa and away from British control during the 1830’s and 1840’s. The reasons for the mass emigration from the Cape Colony have been much discussed over the years. Afrikaner historiography has emphasized the hardships endured by the frontier farmers which they blamed on British policies regarding the treatment of the Xhosa tribes, who often attacked the Boer farmers. Other historians have emphasized the harshness of the life in the Eastern Cape (which suffered one of its regular periods of drought in the early 1830s) compared to the attractions of the fertile country of Natal, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. Growing land shortages have also been cited as a contributing factor. The true reasons were obviously very complex and certainly consisted of both “push” factors (including the general dissatisfaction of life under British rule) and “pull” factors (including the desire for a better life in better country.)

The Great Trek itself led to the founding of numerous Boer republics, the Natalia Republic, the Orange Free State (Oranje-Vrystaat) and the Transvaal being the most notable. The Orange Free extended between the Orange and Vaal rivers – between 1817 and 1831, the country was devastated by the Zulu chief Mzilikazi and his Matabele and almost all this area had been largely depopulated. In 1824 the Voortrekkers from the Cape Colony who were seeking to escape the British settled in the country. They were followed in 1836 by the first parties of the Great Trek. These emigrants left the Cape Colony from various motives, but all were animated by the desire to escape from British sovereignty. In December 1836 the emigrants beyond the Orange drew up in general assembly an elementary republican form of government. The Boers did not escape collision with Matabele raiding parties who attacked Boer hunters who had crossed the Vaal. Reprisals followed, and in November 1837 Mzilikazi and his Matabele were decisively defeated by the Boers and thereupon fled northward. After the defeat of Mzilikazi the town of Winburg (so named by the Boers in commemoration of their victory) was founded in late 1837, a Volksraad elected, and Piet Retief, one of the ablest of the Voortrekkers, chosen “Governor and Commandant-General.”

Retief proposed Natal as the final destination of the Voortrekker migration and selected a location for its future capital, later named Pietermaritzburg. The Voortrekkers migrated into Natal and negotiated a land treaty with the Zulu King Dingane, who then double-crossed the Voortrekkers, killing their leader Piet Retief along with half of the Voortrekker settlers who had followed them to Natal. Other Voortrekkers migrated north to the Waterberg area, where some of them settled and began ranching operations. Another Boer leader, Andries Pretorius, filled the leadership vacuum left by the death of Piet Retief and entered into negotiations with Dingane, demanding that in return for peace Dingane would have to restore the land he had granted to Retief. When Dingane sent an imp (armed force) of around twelve thousand Zulu warriors to attack the local contingent of Voortrekkers in response to the demands, the Voortrekkers defended themselves at the Battle of Blood River fought on 16 December 1838. In the Battle, the vastly outnumbered Voortrekker force of 470 men defeated 10-15,000 Zulu warriors. This date has hence been known as the Day of the Vow as the Voortrekkers made a vow to God that they would honor the date if he were to deliver them from what they viewed as almost insurmountable odds.

The Battle of Blood River – The victory of the Voortrekkers was considered a turning point by the Boers. The Natalia Republic was set up in 1839 but was annexed by Britain in 1843 whereupon most of the local Boers trekked further north joining other Voortrekkers who had established themselves in the Transvaal.

At the same time as the Boers were establishing their republic, the British Cape Colony Government was making treaties with African chiefs, recognising native sovereignty over large areas which Boer farmers had settled, and in doing so seeking to keep the Boer emigrants under British control and to protect both the natives. The Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir George Napier, also maintained that the emigrant farmers were still British subjects. The effect was to precipitate collisions between all three parties. Shortly afterwards hostilities between the Boers and the Griquas broke out. British troops were moved up to support the Griquas, and after a skirmish at Zwartkopjes (May 2, 1845) the administration of the territory was placed in the hands of a British resident, a post filled in 1846 by Captain H. D. Warden. The place chosen by Captain (afterwards Major) Warden as the seat of his government was known as Bloemfontein, which subsequently became the capital of the Orange Free State. Extending between the Orange and Vaal rivers, its borders were determined by the United Kingdom in 1848 when the region was proclaimed as the Orange River Sovereignty by Sir Harry Smith, the Governor of the Cape.

The Boers did not recognize British rule, with the volksraad at Winburg during this period continued to claim jurisdiction over the Boers living between the Orange and the Vaal and as a result, relations between the Boers and the British were in a continual state of tension. There was an armed clas at Boomplats on August 29, 1848, in which the Boers were defeated. The Sand River Convention of 1852 acknowledged the independence of the Transvaal but left the status of the Orange River Sovereignty untouched, but in January 1854 the British abandoned all claims to the Sovereignty. A convention allowing the independence of the country was signed at Bloemfontein on the 23rd of February by Sir George Clerk and the republican committee, and in March the Boer government assumed office and the republican flag was hoisted. The Orange Free State was declared a Republic. This did not bring peace, as the Transvaal Boers wished to unite the two states in a confederation. Thecommando’s of the two sides met but did not fight, the end result being each state acknowledging the absolute independence of the other. Fighting with the Basuto did however go on for some time before the Basuto were defeated and the Basuto country (present day Lesotho) taken under British protection.

The second of the two Boer states, the Transvaal (or, more properly, The South African Republic / Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) was established in 1856. In 1817 the region had been invaded by Mzilikazi, originally a lieutenant of the Zulu King Shaka, who was pushed from his own territories to the west by the Zulu armies. Mzilikazi and his warriors virtually emptied the Transvaal of the previous inhabitants in a series of wars and raids. From 1835 to 1838, Boer settlers began to migrate across the Vaal and came into conflict with Mzilikazi. Early in 1838 Mzilikazi fled north beyond the Limpopo (to current day Zimbabwe where he founded what is now Matabeleland), never to return to the Transvaal. Andries Potgeiter, one of the Boer leaders, after the flight of the Ndebele, issued a proclamation in which he declared that the country which Mzilikazi abandoned was forfeited to the emigrant farmers. After this, many Boer farmers trekked across the Vaal and occupied parts of the Transvaal. On 17 January 1852, the United Kingdom signed the Sand River Convention treaty with 5,000 or so of the Boer families (about 40,000 white people), recognising their independence in the region to the north of the Vaal River, or the Transvaal. In December 1856 the name Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (South African Republic) was adopted as the title of the state

In 1877, before the 1886 Witwatersrand Gold Rush, Britain annexed the Transvaal. The Boers viewed this as an act of aggression, and protested. In 16 December 1880 the independence of the republic was proclaimed again, leading to the First Boer War. The Pretoria Convention of 1881 gave the Boers self-rule in the Transvaal, under British oversight. Kruger was elected president in 1883 and the republic was restored with full independence in 1884 with the London Convention, but not for long. The Gold rush also brought an influx of non-Boer European settlers (called uitlanders, outlanders, by the Boers), leading to a destabilisation of the republic. Kruger was re-elected president in 1888 and 1893, each time defeating Piet Joubert.

In 1895, Cape Premier Cecil Rhodes planned to support an uitlander coup d’état against the Transvaal government. Leander Starr Jameson carried out this plan, without publicly-acknowledged British authorisation, in December of that year – in the ill-fated Jameson Raid. After the failed raid, there were rumours that Germany offered protection to the Boer republic, something which alarmed the British. Kruger won another presidential election in 1898, but the following year British forces were gathering on the borders of the Boer Republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State and fearing Britain’s imminent annexation, the Boers launched a preemptive strike against the nearby British colonies in 1899, a strike which became the Second Boer War. The Second Boer War was a watershed for the British Army in particular and for the British Empire as a whole. It was here that the British first used concentration camps in a war setting. By May 1902, the last of the Boer troops surrendered, mourning the deaths of 26,000 women and children who died in British internment. The independent Boer republic became the Transvaal Colony, which in 1910 became the Transvaal Province of the newly created Union of South Africa, a British Dominion.

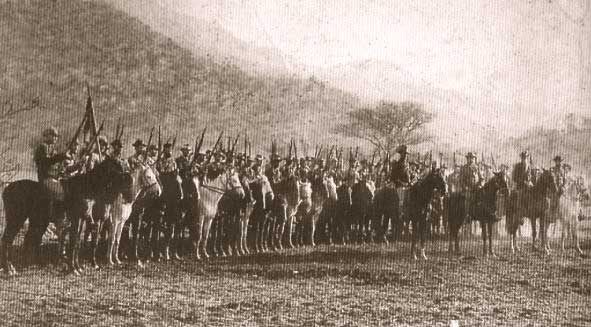

Thus, as we have seen, even prior to the Boer War, the Boers were no strangers to conflict or to fighting both the British, the african tribes or each other for that matter. There was a long tradition of a citizen militia where every able-bodied man fought, and in this fighting had evolved the “Commando” system. Both the Orange Free State and the Transvaal republics issued commando laws, making commando service mandatory in times of need for all male citizens between the ages of 16 and 60. During the Anglo-Boer War ( 1899–1902) the Boer Commandoes formed the backbone of the Boer forces. Each commando was attached to a town, after which it was named (e.g. Bloemfontein Commando). Each town was responsible for a district, divided into wards. Thecommando was commanded by a Kommandant and each ward by a Veldkornet or field cornet (equivalent to a senior NCO). The Veldkornet was responsible not only for calling up the burghers, but also for policing his ward, collecting taxes, issuing firearms and other material in times of war.

Theoretically, a ward was divided into corporalships. A corporalship was usually made up of about 20 burghers. Sometimes entire families (fathers, sons, uncles, cousins) filled a corporalship. The Veldkornet was responsible to the Kommandant, who in turn was responsible to a General. In theory, a General was responsible for four commandos. He in turn was responsible to the Commander-in-Chief of the Republic. In the Transvaal, the C-in-C was called the Commandant-General and in the Free State the Hoofdkommandant (Chief Commandant). Other auxiliary ranks were created in war time, such as Vleiskorporaal (“Meat Corporal”), responsible for issuing rations.

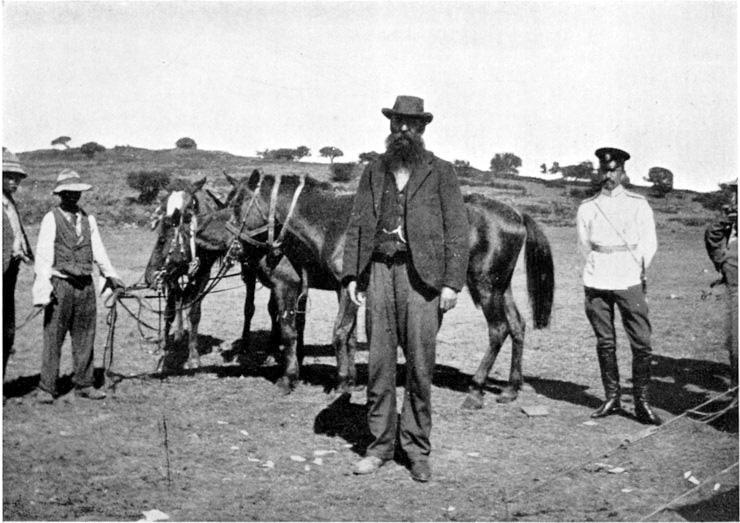

The commando was made up of volunteers, all officers were appointed by the members of the commando, and not by the government. This gave a chance for some exceptional commanders to emerge, such as General Koosde la Rey and General C. R. de Wet, but also had the disadvantage of sometimes putting inept commanders in charge. Discipline was also a problem, as there was no real way of enforcing it. Without straying into a history of the Boer War, the Commandos made up the armed forces of the Boer Republics over the Boer War – in which the fiercely independent Boers had no regular army. When danger threatened, all the men in a district were formed into commandos and elected officers. Being civilian militia, each man wore what they wished, usually everyday neutral or earthtone khaki farming clothes such as a jacket, trousers and slouch hat. Each man brought his own weapon, usually a hunting rifle, and his own horses.

The average Boer citizens who made up the commandos in the Boer War were farmers who had spent almost all their working life in the saddle, and because they had to depend on both their horse and their rifle for almost all of their meat, they were skilled hunters and expert marksmen. Most of the Boers had single-shot breech loading rifle such as the Westley Richards, the Martini-Henry, or the Remington Rolling Block. Only a few had repeaters like the Winchester or the Swiss Vetterli. As hunters they had learned to fire from cover, from a prone position and to make the first shot count, knowing that if they missed the game would be long gone. At community gatherings, target shooting was a major sport and competitions used targets such as hens eggs perched on posts 100 yards away. The commandos became expert light cavalry, making use of every scrap of cover, from which they could pour an accurate and destructive fire at the British with their breech loading rifles which could be rapidly aimed, fired, and reloaded.

Over the course of the Boer War, 50,000 Boer Commando’s faced over 400,000 British and Dominion troops. The Boers were mostly farmers without any formal military training, fighting what was perhaps the greatest power in the world. While the match was uneven from the start, the Boers were fighting on their home ground and used unconventional guerilla tactics to good advantage. They achieved some early victories over the British but in failing to take advantage of their early victories, they gave Britain time to bring overwhelming numbers to the war, whereupon the tide slowly turned against the Boers despite the huge casualties they were inflicting on the British.

Now fighting a defensive war, the Boers lived off the land with help from sympathetic farms. The British responded by removing this advantage. When Kitchener succeeded Roberts as commander-in-chief in South Africa on 29 November 1900, the British army introduced new tactics in an attempt to break the guerrilla campaign and the influx of civilians grew dramatically as a result. Kitchener initiated plans to flush out guerrillas in a series of systematic drives, organised like a sporting shoot, with success defined in a weekly ‘bag’ of killed, captured and wounded, and to sweep the country bare of everything that could give sustenance to the guerrillas, including women and children…. It was the clearance of civilians—uprooting a whole nation—that would come to dominate the last phase of the war. As Boer farms were destroyed by the British under their “Scorched Earth” policy—including the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields—to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base, tens of thousands of women and children were forcibly moved into the concentration camps.

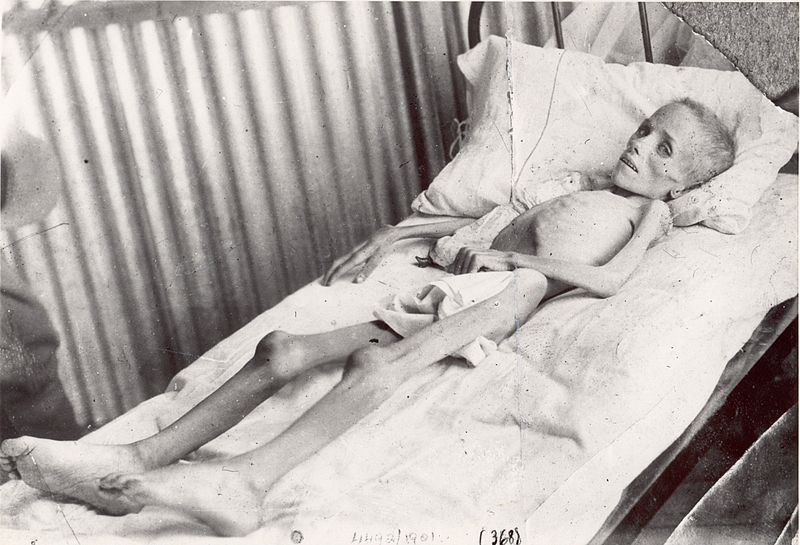

The camps were poorly administered from the outset and became increasingly overcrowded when Kitchener’s troops implemented the internment strategy on a vast scale. Conditions were terrible for the health of the internees, mainly due to neglect, poor hygiene and bad sanitation. The supply of all items was unreliable, partly because of the constant disruption of communication lines by the Boers. The food rations were meager and there was a two-tier allocation policy, whereby families of men who were still fighting were routinely given smaller rations than others. The inadequate shelter, poor diet, inadequate hygiene and overcrowding led to malnutrition and endemic contagious diseases such as measles, typhoid and dysentery to which the children were particularly vulnerable. A report after the war concluded that of around 100,000 Boer prisoners, 27,927 Boers (of whom 24,074 (50 percent of the Boer child population) were children under 16) had died of starvation, disease and exposure in the concentration camps. In all about one in four (25 percent) of the Boer inmates, mostly children, died.

Lizzie Van Zyl – a Boer child deliberately starved to death in a British concentration camp for Boer women and children. Some 50% of all Boer children died in the British Camps.

At the time of the Boer War, Emily Hobhouse told the story of the young Lizzie van Zyl who died in the Bloemfontein concentration camp: “She was a frail, weak little child in desperate need of good care. Yet, because her mother was one of the “undesirables” due to the fact that her father neither surrendered nor betrayed his people, Lizzie was placed on the lowest rations and so perished with hunger that, after a month in the camp, she was transferred to the new small hospital. Here she was treated harshly. The English doctor and his nurses did not understand her language and, as she could not speak English, labeled her an idiot although she was mentally fit and normal. One day she dejectedly started calling for her mother, when a Mrs Botha walked over to her to console her. She was just telling the child that she would soon see her mother again, when she was brusquely interrupted by one of the nurses who told her not to interfere with the child as she was a nuisance”. Quoted from Stemme uit die Verlede (“Voices from the Past”) – a collection of sworn statements by women who were detained in the concentration camps during the Second Boer War (1899-1902).

Late in the war, Lord Kitchener attempted to form a Boer Police Force, as part of his efforts to pacify the occupied areas and effect a reconciliation with the Boer community. The members of this force were despised as traitors by the Boers still in the field. Those Boers who attempted to remain neutral after giving their parole to British forces were derided as “hensoppers” (hands-uppers) and were often coerced into giving support to the Boer guerrillas. (This was one of the reasons for the British ruthlessly scouring the countryside of people, livestock and anything else the Boer commandos might find useful.) Even well after the Boer War, the attitude of the Boers to those who cooperated with the British is well illustrated in the following short story, “The Affair at Ysterspruit” by Herman Charles Bosman.

“The Affair at Ysterspruit” by Herman Charles Bosman

It was in the second Boer War, at the skirmish of Ysterspruit near Klerksdorp, in February 1902, that Johannes Engelbrecht, eldest son of Ouma Engelbrecht, widow, received a considerable number of bullet wounds, from which he subsequently died. And when she spoke about the death of her son in battle, Ouma Engelbrecht dwelt heavily on that fact that Johannes fought bravely. She would enumerate his wounds, and, if you were interested, she would trace in detail the direction that each bullet took through the body of her son.

If you like stories of the past, and led her on, Ouma Engelbrecht would also mention, after a while, that she had a photograph of Johannes in her bedroom. It was with great difficulty that a stranger could get her to bring out that photograph. But she usually showed it, in the end. And then she would talk very fast about people not being able to understand the feelings that went on in a mother’s heart.

“People put the photograph away from them,” she would say, “and they turn it face downwards on the rusbank. And all the time I say to them, no, Johannes died bravely. I say to them that they don’t know how a mother feels. One bullet came in from in front, just to the right of his heart, and it went through his gall-bladder and then struck a bone in his spine and passed out through his hip. And another bullet…” So she would go on while the stranger studied the photograph of her son, Johannes, who died of wounds received at the skirmish at Ysterspruit.

When the talk came round to the old days, leading up to and including the second Boer War, I was always interested when they had a photograph that I could examine, at some farm-house in that part of the Groot Marico District that faces towards the Kalahari. And when they showed me, hanging framed against a wall of the voorkamer – or having brought it from an adjoining room – a photograph of a burger of the South African Republic, father or son or husband or lover, then it was always with a thrill of pride in my land and my people that I looked on the likeness of a hero of the Boer War. I would be equally interested if it was the portrait of a bearded commandant or of a youngster of fifteen. Or of a newly appointed veld-kornet, looking important, seated on a riempies-stoel with his Mauser held upright so that it would come into the photograph, but also turned slightly to the side for fear that the muzzle should cover up part of the veld-kornet’s face, or a piece of his manly chest. And I would think that the veld-kornet never sat so stiffly on his horse – certainly not on the morning when the Commando set out for the Natal border. And he would have looked less important, although perhaps more solemn, on a night when the empty bully-beef tins rattled against the barbed wire in front a a blockhouse, and the English Lee-Metfords spat flame.

I was a school-teacher, many years ago at a little school in the Marico bushveld, near the border of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. The Transvaal Education Department expected me to visit the parents of the school-children in the area at intervals. But even if this huisboek was not part of my after-school duties, I would have gone and visited the parents in any case. And when I discovered, after one or two casual calls, that the older parents were a fund of first-class story material, that they could hold the listener enthralled with tales of the past, with embroidered reminiscences of Transvaal life in the old days, then I became very conscientious about the huisboek.

“What happened after that, Oom?” I would say, calling on a parent for about the third week in succession, “when you were trekking through the kloof that night, I mean, and you had muzzled both the black claf with the dappled belly and your daughter, so that the Mojaja’s kafirs would not be able to hear anything?” And then the Oom would knock out the ash from his pipe on his veldskoen and he would proceed to relate – his words a slow and steady rumble and with the red dust of the road in their sound, almost – a tale of terror or of high romance or of soft laughter.

It was quite by accident that I came across Ouma Engelbrecht in a two-roomed, mud-walled dwelling some little distance off the Government Road and a few hundred yards away from the homestead of her son-in-law, Stoffel Brink, on whom I had called earlier in the afternoon. I had not been in the Marico very long then, and my interview with Stoffel Brink had been, on the whole, unsatisfactory. I wanted to know how deep the Boer trenches were dug into the foot of the koppies at Masgersfontein, where Stoffel Brink had fought. Stoffel Brink, on the other hand, was anxious to learn whether, in regard to what I taught the children, I would follow the guidance of the local school committee, of which he was chairman, or whether I was one of the new kinds of school-teacher who went by a little printed book of subjects supplied by the Education Department. He added that this latter class of school-master was causing a lot of unpleasantness in the bushveld through teaching the children that the earth moved around the sun, and through broaching similar questions of a political nature.

I replied evasively, with the result that Stoffel Brink launched forth for almost an hour on the merits of the old-fashioned Hollander school-master, who could teach the children all he knew himself in eighteen months because he taught them only facts. “If a child stays at school longer than that,” Stiffel Brink added, “then for the rest of the time he can learn only lies.” I left about then, and on my way back, a little distance from the road and half-concealed by tall bush, I found the two-roomed dwelling of Ouma Engelbrecht. It was good, there.

I could see that Ouma Engelbrecht did not have much time for her son-in-law, Stoffel Brink. For when I mentioned his references to education, when I had merely sought to learn some details about the Boer trenches at Magersfontein, she said that maybe he could learn all there was to know in eighteen months, but he had not learnt how to be ordinarily courteous to a stranger who came to his door – a stranger, moreover, who was a school-master asking for information about the Boer War.

Then, of course, she spoke about her son Johannes, who didn’t have to hide in a Magersfontein trench, but was sitting straight up on his horse when all those bullets went through him at Ysterspruit, and who died of his wounds some time later. Johannes had always been such a well-behaved boy, Ouma Engelbrecht told me, and he was gentle and kind-hearted. She told me many stories of his childhood and early youth. She told me about a time when a span of red Afrikaner oxen got stuck with the wagon in the drift, and her husband and the kafirs, with long whip and short sjambok could not move them – and Johannes had come along and he had spoken softly to the red Afrikaner oxen, and he had called on each of them by name, and the team had made one last mighty effort and had pulled the wagon through to the other side.

“And yet they never understand him in these parts,” Ouma Engelbrecht continued. “They say things about him, and I hardly ever talk about him anymore. And when I show them his portrait, they hardly even look at it, and they put the picture away from them, and when they are sitting on that rusbank where you are sitting now, they place the portrait of Johannes face dopwn beside them.” I told Ouma Engelbrecht, laughing reassuringly the while, that I stood above the pettiness of local intrigue. I told her that I had already noticed that there were all kinds of queer undercurrents below the placid surface of life in the Groot Marico. There was the example of what had happened that very afternoon, when her son-in-law, Stoffel Brink, had conceived a nameless prejudice agsinst me, simply because I was not prepared to teach the school-children that the earth was flat. I told her that it was ridiculous to imagine that a man in my position, a man of education and wide tolerance, should allow himself to be influenced by local Dwarsberge gossip.

Ouma Engelbrecht spoke freely, then, and the fight at Ysterspruit lived for me again – Kemp and de la Rey and the captured English convoy, the ambush and the booty and a million rounds of ammunition. It was almost as though the affair at Ysterspruit was being related to me, not by a lonely woman whose some received his death-wounds on the vlaktes near Klerksdorp, but by a burgher who had taken a prominent part in the battle.

And so, naturally, I wanted to see the photograph of her son, Johannes Engelbrecht.

When it came to the Boer War (although I did not say that to Ouma Engelbrecht) I didn’t care if a Boer commander was not very competent or very cunning in his strategy, or if a burgher was not particularly brave. It was enough for me that he had fought. And to me General Snyman, for instance, in spite of the history books’ somewhat unflattering assessment of his qualities, was a hero, nonetheless. I had seen General Snyman’s photograph somewhere: that face that was like Transvaal blouklip: those eyes that had no fire in them, but a stubborn and elemental strength. You still see Boers on the backveld with that look today.

In my mind I had contrasted the portrait of General Snyman and Matts Gustafsson, the Finn who had come all the way from Europe to shoulder a Mauser for the Transvaal Republic. Gustafsson, poet and romantic, last ditch champion of the forlorn hope and the heroic lost cause. …. Oh, they were very different these two men, Gustafsson, the Finnish gold-miner and poet and Snyman, the Boer. But I had an equal admiration for both of them.

Anyway, it was well on towards evening when Ouma Engelbrecht, yielding at last to my cajoleries and entreaties, got up slowly from her chair and went into the adjoining room. She returned with a photograph enclosed in a heavy black frame. I waited, tense with curiosity, to see that portrait of that son of hers who had died of wounds at Ysterspruit, and whose reputation the loose prattle of the neighborhood had invested with a dishonour as dark as the frame about his photograph.

Flicking a few specs of dust from the portrait, Ouma Engelbrecht handed over the picture to me.

And she was still talking about the things that went on in a mother’s heart, things of pride and sorrow that the world did not understand, when, in unconscious reaction, hardly aware of what I was doing, I placed beside me on the rusbank, face downwards, the photograph of a young man whose hat-brim was cocked on the right side, jauntily, and whose jacket with narrow lapels was buttoned up high. With a queer jumble of inarticulate feelings I realized that, in the affair at Ysterspruit, they were all Mauser bullets that had passed through the youthful body of Johannes Engelbrecht, National Scout.

Notes: Rusbank is Afrikaans for couch. The Boers generally used Mauser Rifles and the National Scouts were a unit of Boers who fought for the British. To say they were not liked by the Boers who fought on against the British is somewhat of an understatement as the following short article illustrates all too well.

“Betrayal”

Troopers John Beck and Frederick Nel, amongst other National Scouts were killed in action by their former friends of the Heidelberg Commando on 24 July 1901 at Braklaagte. They were buried next to each other in the Kloof Cemetery, Heidelberg. During the same action Scheepers, Danie Maartens’ brother-in-law, was badly wounded. Scheepers and a group of National Scouts had turned his (Danie Maarten’s) sister and her daughter out of their house in nightclothes before burning it. They then drove them into the freezing veld in front of their horses for a kilometer before abandoning them. Danie found his wife and child the following morning in a critical condition from the cold.

After the Braklaagte action Danie demanded to see the wounded Scheepers, who was under armed guard. Scheepers crawled towards Danie, begging for mercy. “Danie told him that he wished to hear nothing, but wanted to shoot him between the eyes. He aimed, fired, then climbed on his horse and rode away.” Two other former friends captured during this action, Piet Bouwer and Roelf Van Emmenes, were tried and later executed. This was a particularly emotional execution as it was carried out by blood relatives, friends, and ex-pupils of the Schoolmaster, Piet Bouwer.

The Second Boer War cast long shadows over the history of the South African region. The predominantly agrarian society of the former Boer republics was profoundly and fundamentally affected by the scorched earth policy of Roberts and Kitchener. The devastation of the Boer population in the concentration camps and through war and exile were to have a lasting effect on the demography and quality of life in the region. Many exiles and prisoners were unable to return to their farms at all; others attempted to do so but were forced to abandon the farms as unworkable given the damage caused by farm burning and salting of the fields in the course of the scorched earth policy. Destitute Boers swelled the ranks of the unskilled urban poor competing with the “uitlanders” in the mines. It’s certainly easy to see why the Boers had no love for the British and why most Boers opposed any entry into either WW1 or WW2 on the side of the British.

After the end of the Boer War in 1902, the Commandos were disbanded, although many Boers formed themselves into clandestine “shooting clubs” – commandos in all but name. With the white population of the newly-formed Union of South Africa existing in still heavily-armed rival English and Afrikaans-speaking factions, and the new army tried to channel these aggressive tendencies and in 1912, the Commandos were reformed as an Active Citizen Force in the Union Defence Force. When the First World War broke out, the Union sent an expeditionary force of 67,000 men into neighboring German South-West Africa and overwhelmed the tiny German garrison there. The army also showed its loyalty to the British Empire by quickly crushing an attempted Boer revolt, using many Afrikaans-speaking troops in the effort. Britain officially removed its garrison from South Africa in 1921, turning over responsibility to the Union Defence Forces. New legislation in 1922 re-established conscription for white males over the age of 21 for four years of military training and service. UDF troops assumed internal security tasks in South Africa and quelled several revolts against South African domination in South-West Africa. South Africans suffered high casualties, especially in 1922, when an independent group of Khoikhoi – known as the Bondelswart-Herero for the black bands that they wore into battle – led one of numerous revolts; in 1925, when a mixed-race population – the Basters – demanded cultural autonomy and political independence; and in 1932, when the Ovambo population along the border with Angola demanded an end to South African rule.

As a result of its conscription policies, the UDF increased its active-duty forces to 56,000 by the late 1930s; 100,000 men also belonged to the Active Citizen Force, which provided weapons training and practice. The permanent army however remained small and under-funded, and during the 1930s served mostly as a job-training program for unemployed young men. Several times it deployed against striking industrial and railway workers. In 1939, Britain’s declaration of war against Germany caused a serious political upheaval in South Africa. For three days debate raged, until the World War One hero J.C. Smuts split the ruling United Party to oust prime minister J.B.M. Hertzog, an Afrikaner nationalist who wanted to keep South Africa neutral. Smuts rammed through the declaration on 6 September, but anger over his action smoldered for years afterwards, as has been previously commented. The army quickly began to expand, but under some limitations. At first South Africa began conscripting all young white men aged 17 to 21, but this led to political unrest amongst many of the Boer communities. In February, 1940, the army reorganized itself, separating the conscripts into those with a responsibility to serve only within the Union and volunteers who took the “Africa Oath” and could serve anywhere on the continent — but not elsewhere. These men made up the Active Citizen Force, and these units would form the South African divisions in Egypt.

Nevertheless, as has been mentioned, a considerable percentage of the Afrikaners opposed entry into WW2, opposed conscription and refused pointblank to fight for the British. The Ossewabrandwag were by no means the most extreme of this group. However, where the Ossewabrandwag were unique was in their desire to assist Finland in their fight against the Russians. To the volunteers, the parallels were obvious. A small nation which desired nothing more than independence and to be left alone was fighting a great power which sought to conquer and occupy them. And not only that, this was a small country from whence volunteers had come to help the Boers fight their own war. And while the Boers had lost their war, perhaps with enough assistance the Finns could win theirs and a debt of honour could be repaid. For the government of Jan Smuts, the desire of the Ossewabrandwag to send volunteers to Finland was a godsend. Rather than opposition to fighting alongside the British, here was an opportunity to divert the attention of the Boers who opposed fighting the Germans into the support of a war that everyone saw as just and behind which all South Africans could unit in praising the volunteers.

Smuts committed the South African Government to wholeheartedly supporting the De La Rey Commando by any and all means possible. And so, the De La Rey Commando answered the Call for volunteers to assist Finland with the backing of the entire nation.

Blood River’s Calling: The spirit of the Boer Volunteers was driven by the memories of the Boer War and the warrior spirit that had led the Boers to fight against heavy odds for almost their entire existence as a nation. (Note: I’m going to be editing the video with photos that better fit the ATL, but in the meantime….)

The De La Rey Battalion embarked on the SS Mariposa (Matson Lines) and sailed for Belfast in early March 1940 after two months of hard training, in company with the New Zealand ship SS Awatea and their escort, the light cruiser HMNZS Achilles. After a six weeks of training with the Maavoimat, the De La Rey Commando moved up to the front in mid-May 1940, where they found themselves responsible for a sector on the Syvari River, the frontline with the Red Army that ran from Lake Ladoga to Lake Onega. The soldiers of the De La ReyCommando called their sector “Die Kaplyn” – “The Cutline” – due to the wide band of forest that had been cleared along the banks of the Syvari in order to offer a clear field of fire. Their task was to patrol and guard their sector of the Cutline against any incursions and river crossings by the Red Army. For three long months the Commando guarded the Syvari, four weeks on the front followed by two weeks in the rear. The fighting was of low intensity, patrols and skirmishes, raids across the river into the Red Army positions to take prisoners and gain intelligence, ambushing Red Army patrols and Red Army raids across the river, always on guards, always taking casualties in the ones and twos. The ongoing small scale fighting and the constant casualties made an impact on the Boer volunteers, many of them young men aged from eighteen into their mid-twenties.

“Die Kaplyn” (“The Cutline”) – Bok van Blerk

Tussen bosse en bome, Tussen grense wag ons almal vir more

Maar op agtien was ons almal verlore, Hoe kon ons verstaan

En wie weeg nou ons lewe, Want net God alleen weet waarvoor ons bewe

Want op agtien wou ons almal net lewe

Net een slag toe was jou lewe verby

Between bushes and trees, Between borders we all wait for tomorrow

But at eighteen we were all lost, How could we understand

And who weighs our lives now, Because only God alone knows why we quiver

Because at eighteen we all just wanted to live

Just one flash and your life was gone

Roep jy na my, Roep jy my terug na die Kaplyn my vriend

Deur die jare het die wêreld gedraai, Toe ons jonk was hoe sou ons dit kon raai

Soek jy na my, Soek jy my nou in die stof en jou bloed

Jy’t gesê jy hoor hoe God na jou roep

Toe’s dit als verby…

Are you calling me, Calling me back to the ‘Die Kaplyn’ my friend

The world has turned over the years, When we were young how could we have guessed

Are you searching for me, Searching for me now in the dust and your blood

You said you heard how God was calling you

Then it was all over…

Na al hierdie jare, Ver verlore dryf ons rond in ons dade

Net soldate leef met grense se skade, Hoe kan julle verstaan

Want daai bos vreet ons spore, In die donker bos was broeders gebore

In die donker saam gebid vir die more

Maar met net een slag jou lewe verby

After all these years, Far gone do we drift around in our deeds

Only soldiers live with damage caused by borders, How can you understand

Because the bush gobbles our tracks, In the dark bush brothers were born

In the dark we prayed together for tomorrow

But in one flash your life was over

Roep jy na my, Roep jy na my terug na die Kaplyn my vriend

Deur die jare her die wêreld gedraai, Toe ons jonk was hoe sou ons dit kon raai

Waar is jy nou, Is jou naam dan op ons mure behou,

Jy was nooit vereer en niemand gaan nou, Oor jou lewe skryf en wat jy nog wou…,

En by daai muur, Staan ek vir ure,

Maar waar’s jou naam nou my vriend, Kan hull nie verstaan…

Jong soldate vergaan…, Sonder rede dra hulle die blaam…

Are you calling me, Are you calling me back to ‘Die Kaplyn’ my friend

The world has turned over the years, When we were young how could we have guessed

Where are you now, Is your name then retained on our walls

You were never honoured and no one will, Write about your life and what you still wanted…

And at that wall, I stand for hours

But where’s your name now my friend, Can they not understand

Young soldiers perish…, Without reason they carry the blame…