Unlike Canada and South Africa, Australia’s entry to WW2 occurred on the 3rd of September 1939 with no debate. At 9.15 p.m. the voice of the Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, was heard by listeners throughout Australia . “It is my melancholy duty”, he said, “to inform you officially that, in consequence of a persistence by Germany, in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war. ” Australia asked London to notify Germany that Australia was an associate of the United Kingdom. This position received almost universal public support, though there was little enthusiasm for war. On the 5th of September, after the formal declaration of war, it was announced that militiamen would be called up 10,000 at a time for sixteen days to provide relays of guards on “vulnerable points.” Since there seemed to be no sign of attack by Japan, the eyes of most Australians were fixed on a war in which they might have to shoulder their rifles and defend the status quo against Germany. When the Federal Parliament met on 6th September Opposition members offered no criticism of the Government’s action in entering the war; it was soon evident that the burning question was whether or not Australia would send forces overseas—the problem which had coloured every debate on defence in Parliament for more than twenty years.

Meanwhile, the Australian Government waited on advice from the British Government as to what form of assistance was needed. The Australian Government was warned that there must be preparation for a long war. “We therefore hope,” the cablegram continued, “that Australia will exert her full national effort including preparation of her forces with a view to the dispatch of an expeditionary force.” The policy of the United Kingdom Government, the cablegram stated, was to avoid a rush of volunteers, but she would nevertheless welcome at once, for enlistment in United Kingdom units, technical personnel, such as fitters, electricians, mechanics, instrument mechanics, motor vehicle drivers and “officers with similar qualifications and medical officers .” If Japan gave no evidence of a friendly attitude, it might be thought unwise for Australia to dispatch an expeditionary force overseas but the Commonwealth Government could assist by holding formations ready at short notice for reinforcement of Singapore, New Zealand, or British and French islands in the Western Pacific. Uncertainty about Japanese policy was not the only reason for the British Government’s hesitation to request military aid in the main theatre of war and the somewhat cautious tone of the communication. Britain lacked military equipment, and knew that the Dominions could not fully arm their own expeditionary forces; indeed that Australia, for example, was still awaiting the delivery of modest orders from Britain that had been lodged four years before. This general shortage had already set up in Britain a struggle for resources between the fighting Services.

Until the Munich crisis Britain had been planning “a war of limited liability” in which only five regular divisions would be prepared for service on the Continent. After Munich, however, Britain reached an agreement with France whereby she would have thirty-two divisions (including six of regulars) ready for oversea service within a year after the outbreak of a war. This entailed doubling the Territorial Army yet the equipment of the unexpanded Territorial Army was then no better than that of the Australian militia. After war broke out the British Government decided to prepare to equip fifty-five divisions (her own thirty-two and twenty-three from the Dominions, India and “prospective Allies). This estimate was evidently based on an estimate that contingents from the Dominions would be on the scale of 1918, when there were six Australian divisions (including one mounted), four Canadian divisions, one “Anzac” mounted division and one New Zealand division in the field. It was already evident that it would be impossible for Australia to be at war and Australians to stand aloof. If no expeditionary force was raised no regulation could prevent Australians from finding their way to other Allied countries to enlist and the British Government had already asked that professional men and technicians be allowed to volunteer for service in the British forces.

Within a day after the declaration of war by Britain and France the Japanese Government shed a little light on its policy by informing the belligerents of its intention to remain not “neutral” but “independent.” Thus, while fear that Japan would take advantage of the preoccupation of Britain and France in Europe had always to be taken into account, it appeared that, for the present, either she was too heavily committed in China—and Manchuria where a minor war against Russian frontier troops was in progress—or she intended to wait and see how affairs developed in Europe. Nevertheless plans for sending Australian expeditionary forces abroad had to take into account the possibility of both of Germany’s allies, Italy and Japan, being at war. In that event Britain and France would be outnumbered at sea and, unaided, could not command the oceans both in the West and the East. Moreover, the British and French Air Forces were perceived as inferior both in Europe and the East to those of their enemies or potential enemies.

In addition to fear of Japan, lack of equipment, and the opposition of the Labour party (for the Labour Party remained strongly opposed to sending an expeditionary force overseas), there were other brakes on the sending abroad of a military force. One of these was the widespread conviction that, in the coming war, armies would play a far less important part than in the past. It had become apparent between the wars that the air forces would inflict greater damage in a future struggle than in 1914-18 and also that the increasing elaboration of the equipment of each of the fighting Services would require that a greater proportion of a belligerent s’ manpower than hitherto would be needed in the factories and in the maintenance units of the forces. Enthusiasts had expounded these points with such extravagant eloquence that the impression had become fairly general that armies, and in particular, infantry would play a minor part in the coming war, an impression which air force leaders and industrialists had done much to encourage. An additional brake on a full-scale war effort was the opinion not noised abroad but nevertheless widely entertained at the time by leaders in politics and industry in Australia as in England—and Germany—that an uneasy peace would be negotiated leaving Germany holding her gains in eastern and central Europe.

However, a chain of events had been set in motion. War had been declared, Britain was in danger. Australians should be there. To probably a majority of Australians the problem was seen in as simple terms as that. And on 9th September the New Zealand Government, which faced a similar situation, announced that it had decided to raise a “special military force” for service in or beyond New Zealand, and as a first step 6,600 volunteers were to be enlisted. In Australia most of the newspapers had from the beginning urged that an expeditionary force be formed, and as days passed and no decision was announced, their demands became more vehement. “The outward complacency of a Federal Government actually engaged in carrying on a war,” declared the Sydney Morning Herald on 14th September, “is beginning to arouse more than astonishment among the Australian public.” Finally, on the 15th, Menzies, in a regular Friday night broadcast, announced that a force of one division and auxiliary units would be created—20,000 men in all—for service either at home or abroad “as circumstances permit.” The new infantry division, he said, would consist of one brigade group from New South Wales, one from Victoria and one from the smaller States (as had the 1st Division of the A.I.F. of 1914) . Privates and NCOs must be over 20 and under 35, subalterns under 30, captains under 35, majors under 40 and lieut-colonels under 45, and preference would be given to single men not in “essential civil jobs.”

In a broadcast address a week later he said “that Great Britain did not want Australia to send a large force of men abroad” and expressed the opinion that “any active help that Australia gave would be in the air.” “Every step we take,” he added, “must be well considered, and we must not bustle around in all directions as if we were just trying to create an illusion of activity. We must see that every step is a step forward.” At the same time as it was announced that the militia would be called up 10,000 at a time to continue training and to guard vulnerable points it was also announced that “experts” would cull out militiamen in reserved or exempted occupations based on an occupational list. This list provided, for example, that tradesmen such as shearers and carpenters would not be accepted if they were over 30, foremen if over 25, brewing leading hands over 25, there was a complete ban on the enlistment of engineers holding degrees or diplomas. On 10th October 1939 the War Cabinet decided not to fill gaps in the militia caused by enlistment in the A.I.F. and discharges to reserved occupations – and married men were to transfer to the reserve after one month’s training. These decisions threatened to reduce the strength of the militia by half, since 10,000 vacancies in the AIF. had been allotted to it, more than 6,000 men had been lost to the reserved occupations in the first few weeks of the war, and an additional 16,000 men of the force were married.

In September 1939 the militia had a strength of about 80,000 men – about 40 per cent of the full mobilisation strength of the four infantry and two cavalry divisions, the independent brigades and ancillary units. Considerably more than half the citizen soldiers of September 1939 had been in the force less than a year. All divisional and brigade commanders and most unit commanders had served as regimental officers in the war of 1914-18 and the junior officers had been trained under these experienced leaders, but the strength in veteran leaders in the senior ranks was offset by an extreme shortage of regular officers to fill key staff posts. A divisional commander was fortunate if he had two Staff Corps officers on his own staff, four as brigade majors and four or five as adjutants. The force was armed with the weapons which the A.I.F. had brought back in 1919, the infantry with the Lee-Enfield 303 rifles and Lewis and Vickers machine-guns, the artillery regiments with 18-pounder field guns and 4.5-inch howitzers. Most of the signal and engineer equipment was obsolete, nor was there enough equipment to meet active service conditions. Obsolescence and deficiency are relative terms, there were armies in Europe which were not as well equipped as the Australian militia, but the Australians judged their force by the standard of the British regular army. There were not enough anti-tank and modern anti-aircraft guns in Australia to fully equip one unit. The tank corps consisted only of a small training section with a few out-dated tanks. The only weapons that the Australian factories were capable of manufacturing for the army were anti-aircraft guns of an out-dated type, rifles and Vickers machine-guns, though it was hoped to soon be producing Bren light machine-guns to replace the Lewis guns which were already decrepit and would soon be quite worn out. Machine-gun carriers and 3-inch mortars had been ordered but were not yet being produced. If the militia were to be armed from Australian sources it would be necessary to manufacture up to date field, anti-aircraft and anti-tank guns, mortars, pistols, grenades, armoured fighting vehicles, a wide variety of other technical gear, and thousands of trucks. To meet these requirements would demand expenditure on factories and war material on a far higher scale than Australian Governments had hitherto contemplated.

On 29th September the Minister for Supply and Development submitted to the War Cabinet a proposal for capital expenditure on new munitions projects amounting to £2,755,000 “to bring munitions production up to a condition whereby the war may be prosecuted effectively.” The largest item but one was £750,000 to build a second explosives filling factory, because the existence of only one such factory which a single air attack or a single accident might put out of action had long been an anxiety . This was agreed to but the largest item, £855,000, to extend the Commonwealth’s only gun factory and its ammunition and explosives factories so that they could produce 25-pounder field guns and ammunition, was not approved. A few weeks later a proposal to buy 2,860 motor vehicles, including 664 motor cycles, for the militia and 784, including 180 motor cycles, for the new division was approved. Those numbers, however, would not equip either force for war, but only for training, the vehicles on the war establishment of one infantry division at that time being about 3,000. In this way plans for adequately equipping the army in general and the A.I .F. in particular were allowed to proceed at a cautious pace. Treasury officials seemed resolved that the war should not be an excuse for undue extravagance on the part of the Services. Fortunately the proposal to make 25-pounder guns was approved, with Cabinet assent to the expenditure of £400,000 (less than half the original sum) to provide for the manufacture of 25-pounder field guns and 2-pounder anti-tank guns. There had then, however, been a delay of four months in initiating the manufacture of modern field guns, in spite of the fact that at the outset, in September, the War Cabinet had been told that the guns with which the militia was equipped were “obsolete” although “quite effective for local defence” – a somewhat optimistic description of them.

Thus far, the Government had called for volunteers for an expeditionary force, but on a minimum scale, and had approved a plan of militia training, but one which would take only 40,000 men at a time away from fields and factories. By 15th September 1939 it had approved expenditure on the fighting Services and munitions amounting to £40,000,000—as much, as Menzies pointed out, as Australia had spent in 1915-16 “with the war in full blast and large forces overseas”—and the Services were asking for more and more. Relative to pre-war military expenditure it was indeed a huge sum, but, in relation to the demands that would be made if full mobilisation became necessary, it was small indeed and was in any event based on an assumption that the greater part of the equipment the Australian forces needed could be bought from Britain. Throughout October 1939 a decision about the future of the Second A.I.F., as the new force was named, was deferred. The danger of attack by Japan was a constant concern – if Japan was hostile, no troops could be sent out of Australia except to reinforce Far Eastern garrisons and localities. The War Cabinet decided, on 25th October, to inform the Dominions Office that the period needed to train the Second A.I.F. even up to the stage where it might be possible to send units abroad for garrison duty and further training would “afford a further opportunity for the international position to clarify itself as to the possibility of the dispatch of an expeditionary force from Australia.” Meanwhile the staffing and organisation of that force proceeded. It was named the 6th Division.

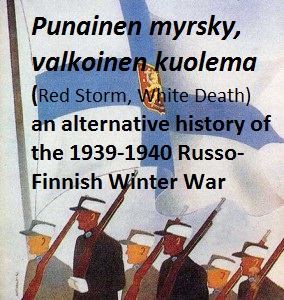

This brings us up to the early November 1939 timeframe, the arrival of the Finnish Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team in Sydney and the start of the Finnish “information war” in Australia. But before we move to looking at the activities of the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team in Sydney and the interaction of these with regard to the groundswell in support for Finland, we’ll take a quick look at pre-WW2 Finnish immigration to Australia and the participation of Australian-Finns in WW1 with the Australian Army – for this was a facet of Finnish life in Australia that the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team in Sydney would be quick to grasp and utilize to advantage.

Early Finnish immigration to Australia prior to WW1 and Australian-Finns in WW1

Toisen polven australiansuomalainen Arthur Nikolai Ronnlund kuului vuonna 1917 Australian joukkoihin Ranskassa ja joutui saksalaisten vangiksi. Kuva Siirtolaisinstituutti, Turku / Second-generation Australian-Finn Arthur Nikolai Rönnlund with the Australian troops in France in 1917. He was captured by the Germans. Picture from the Migration Institute, Turku, Finland

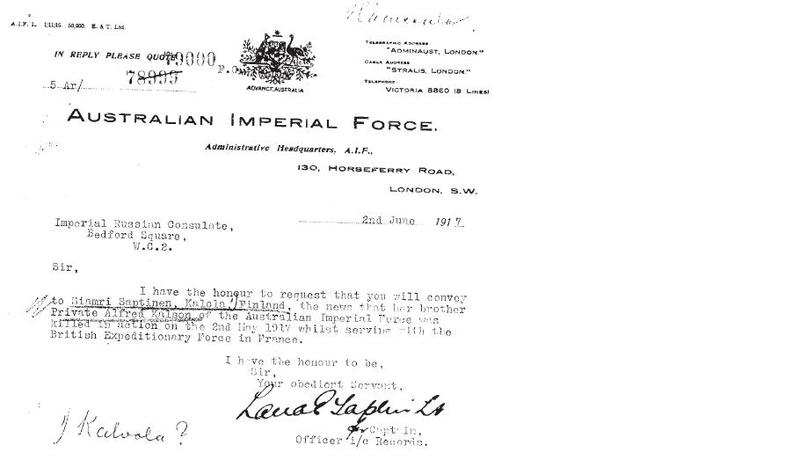

Finnish immigration to Australia began in Australia’s early days. Even before 1900, Finns had been arriving in Australia in small numbers, generally sailors deserting from sailing ships or small groups of young women immigrants. The young women were usually familiar with a Finn already in Australia and were met on arrival at their destination. Early Finns in Australia remembered as many as a hundred men, but the number of Finnish girls could be counted on the fingers of two hands. The outbreak of WW1 resulted in the immediate enlistment of volunteers, a number of whom were Finnish. These “Australian-Finns” belonged to two main categories – Finns who were resident in Australia, generally labourers or sailors who lived in the cities – primarily Sydney and Melbourne, and a smaller group of second-generation immigrants who had grown up as adults in Australia. So far, some 246 Finns have been identified in the Australian armed forces in WW1, based on source material in the Australian National Archives.

The first major fighting the Australian forces were involved in was in the Middle East against the Turks. With the invasion at Gallipoli and the ANZAC landings on April 25th, 1915, fierce fighting took place as the Turks tried to drive the invaders into the sea. Australian losses were 8,587 killed and 19,367 wounded while the new Zealand Army lost 431 killed and 5,140 wounded. Two Australian-Finns are known to have been killed at Gallipoli – Thomas Lind, killed in action on 26 April 1915 (i.e. during the actual landing), and Jacob L. Jofs (Jåfs), whose date of death was 18 November 1915.

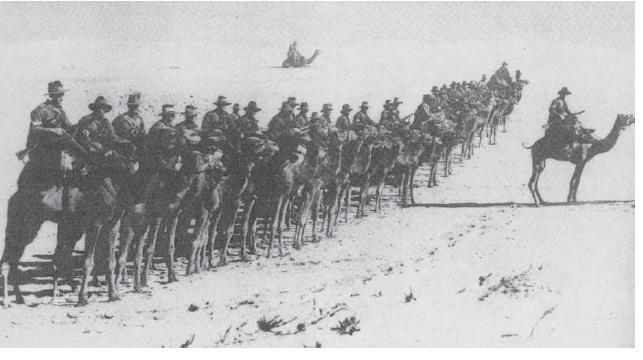

After the withdrawal from Gallipoli, the AIF was reorganized in Egypt and gradually transferred to France from March 1916 onwards. Australian Mounted Rifle units remained in the Middle East fighting the Turks, and the majority of the “British” troops in the Camel Corps were also Australian. These units advanced across the Sinai and battled the Turks in Palestine. At least one Australian-Finn is known to have died fighting with the Camel Corps. He was Wilhelm Konsten, born in Rauma in 1895. Konstens fell in battle in Jerusalem in 19 April 1917, aged 22 years. He already had been awarded two medals for bravery. Australian losses in the Middle East were minor compared to those that would be experienced on the Western Front. At the Somme, the Australians lost 5,500 men in one day. By the end of 1916, 42,000 Australians had been killed or wounded on the Western Front and many Australian-Finns are recorded as having died at Ypres. Overall, current information is that about 250 Australian-Finns fought in the ranks of the Australian military and of these 53 are known to have been killed. It is believed that all but three died on the Western Front. While throughout the Australian armed forces, the average death rate was 17.9%, the Australian-Finn death rate was 21.2%. One of the causes of the proportionally higher mortality rate was that the Australian-Finns were generally found in the forefront of the battle.

The photo shows Australian-Finn Carl V. Suominen at a military camp near Melbourne in 1916. (Kuva, Siirtolaisinstituutti, Turku, Finland)

he Australian Imperial Camel Corps Brigade was formed in December 1916 and took part in fighting in the Sinai and Palestine. Australian-Finns also served in the Camel Troops, Wilhelm Konsten was killed at Jerusalem 19 April 1917.

Prior to 1921, the Australian census recorded Finns as Russians, so numbers can only be estimated. But according to the 1921 census, there were 1,358 persons born in Finland then living in Australia. Of these, 1,227, or 90%, were men. The largest age group were 25-30 year olds. During WW1, a number of young Finnish men left Australia to avoid having to join the Army. And in 1917, after Finland gained independence, a number of Finns returned to Finland from Australia via Siberia. As, in 1921, new immigration from Finland to Australia had not really started up, it can be estimated that at the time of the start of WW1 there were about 1,500 Finns in Australia. In addition, there were also a number of children born to Finnish parents resident in Australia. Given these numbers, it is estimated that about a fifth of the Finns in Australia joined the Australian armed forces and of these, one in five died.

Pihlajaveteläinen Niilo Kara osallistui vapaaehtoisena ensimmäiseen maailmansotaan Australian joukoissa haavoittuen rintamalla. Toivuttuaan hän palasi Australiaan ja toimi jonkin aikaa farmarina. Kuva Siirtolaisinstituutti, Turku / Niilo Kara fought in the First World War as a volunteer in the Australian Army, where he was wounded at the front. After recovering, he returned to Australia and was for some time a station hand (a “station” in the Aussie and Kiwi vernacular is a very large sheep or cattle farm). Following the outbreak of the Winter War, Niilo Kara would speak frequently around New South Wales at fund-raising events in support of Finland. Picture from the Migration Institute, Turku, Finland

What made so many Finns take up arms for a foreign country? The Finns who joined the Australian Army were usually young men, and very often sailors, who had been left ashore in a port. During the war, cargo ships could not go on as before, and for unemployed seamen, joining the army was often one of the few options available. The armed forces also offered something new, interesting and exciting and the adventure probably overweighed the economic factors as a reason to join the military. For second-generation Finnish-Australians, the main motivation to join the Army was usually, as with almost all the volunteers, a strong sense of Australian identity and a sense of duty to the country and the Empire.

And this was something that Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus would constantly highlight – that Finns had fought and died for Australia in WW1 out of selfless patriotism and loyalty to their adopted country. And now, when Finland was in need, Finnish Australians were rallying to support their old homeland, and asking for the support of all Australians to help their country remain free from Soviet tyranny – and the Soviet Union was the ally and friend of Nazi Germany, with whom Australia was now at war. Stalin and Hitler were but two faces of the same totalitarian enemy whom free peoples around the world were fighting.

Appendix: (identified) Finnish-Australian troops killed over 1914-18

Gallipoli

– Jofs, Jacob L., Vöyri, sotilas, kuoli 18.11.1915;

– (SSSP: Jåfs, Johan Gustaf, kaatunut Egyptissä 18.11.1915)

– Lind, Thomas, killed in action 26.4.1915.

Palestiina

– Konsten, Alli Wilhelm, s. 1895, Rauma, merimies, sotilas, kuoli taistelussa 19.4.1917, 22 v. Imperial Camel Corps, Jerusalem, Palestiina, BWM, VM.

Ranska (France)

– Alenius, Edward E. , Helsinki, kuoli taistelussa 3.8.1916 Ranska, BWM, VM.

– Asplond (Asplund/Haapaniemi), Hugo, Vaasa, kuoli haavoihin 15.10.1917 Belgia, BWM, VM.

– Backman, Onnie, Yarkup(?) , Finland, kuoli taistelussa 29.7.1917 Pozieres, Ranska, BWM, VM.

– Backman Evert I., Kristiinankaupunki, kuoli haavoihin 25.9.1917 Belgia, 37 v.MWM, VM.

– Borg, Charles Leonard kuoli taistelussa 13.4. 1918.

– Broström, John kuoli taistelussa 8.8.1916; (SSSP: Broström, Johan Ferdinand, s. 11.3.1894, Mustio, Karjaa, merimies, kaatunut Ranskassa 8.8.1916)

– Carlson (Vesala), Victor Köyliö, kuoli taistelussa 14.11. 1916 Somme, Ranska, 1914–15 Star, BWM, VM.

– Edman, Alfonso E., Helsinki, kuoli taistelussa 28.12. 1916 Lesboefs,Ranska, BWM, VM; (SSSP: Idman, Alfons Eugén, s. 23.11.18888, Helsinki, kaivertaja, kaatui Ranskassa 28.12.1916)

– Ek Emil, Turku, kuoli taistelussa 20.9. 1917 Zillebeke, Belgia, 1914–15 Star, BWM, VM.

– Ekland, Adolf, Hanko, kuoli taistelussa 1.9.1916 Villiers-Bretonneux, BWM, VM.

– Falk, Paul Richard Eugene Napoleon Nicholas, s. 5.4.1893, Helsinki (Hanko), aliupseeri, kuoli taistelussa 25.9.1918 Star, BWM, VM; (SSSP: Falk, Paul Richard, Eugen, s. 5.4.1893, Helsinki, aliupseeri, kaatunut Ranskassa syyskuussa 1918, haudattu Tincourtin sotilashautausmaalle 25.9.1918)

– Graubin, John G., s. 6.12.1881, kuoli taistelussa 26.9.1917 Ypres, länsirintama, BWM, VM; (SSSP: Granlin, Johan Gustaf, s. 6.12.1881, Helsingfors, kaatui Ranskassa 26.9.1917)

– Halona, Mikael (isä Helsingissä), kuoli taistelussa 14.8.1917 Belgia, BWM, VM.

– Hanson, Hugo, kaatunut taistelussa 8.8.1918; (SSSP: Hansson, Johan Hugo, s. 22.1.1894, Pernaja, kaatunut Ranskassa 1918)

– Henderson, John, kuoli taistelussa 21.3.1918.

– Hendrickson, John, kuoli Ranskassa 18.12.1916.

– Holmen (Vastamaa), Kustaa Victor, Kullaa, kuoli haavoihin 5.7.1918 Ranska, 29 v. BWM, VM.

– Johanson, Gustaf, kuoli taistelussa 4.7.1918.

– Johnson, Karl Johannes, kuoli taistelussa 3.9.1916.

– Jorgensen, Carl, kuoli Englannissa 6.11.1918.

– Kalson (Karlson?), Alfred, Finland, sotilas, kuoli taistelussa 2.5.1917 Ranska, BWM, VM.

– Karllström, Gunnar, kuoli haavoihin 11.1.1917.

– Knappsberg, Oscar Bruno, kuoli haavoihin 7.5.1917; (SSSP: Knappsberg, Oskar Bruno, s. 29.12.1889, Mustio, Karjaa, tehtaantyömiehen poika, kaatunut Ranskassa 18.5.1917)

– Kortman, Ernst H., Helsinki, kuoli haavoihin 22.8.1917 Belgia, 1914–15 Star, WM, VM; (SSSP: Kortman, Ernst Hjalmar, s. 15.4.1879, Helsinki, merimies, kuollut Ranskan rintamalla ilmeisesti 1918 joskin todellista kuolinajankohtaa ei tiedetä)

– Kotkamaa Johannes, kuoli taistelussa 19.8.1917.

– Kärnä, Alfred, Kankaanpää, kuoli taistelussa 3.5.1917 Ranska.

– Lauren, Karl Walter, kuoli haavoihin 12.7.1918.

– Lehtonen, Johan Alfred s. 1891 Helsinki, merimies, kuoli taistelussa 3.1.1917.

– Liljestrand, Erik Arvid, s. 1884, Kirkkonummi, merimies, naimaton, sotilas, kuoli Englannissa 9.6.1918, 34 v.; (SSSP: Liljestran, Erik Arvid, s. 5.1.1884, merimies, Australia, kuoli sodan aiheuttamaan haavaan 9.6.1918)

– Lindholm, John, kuoli taistelussa 1.10.1918.

– Ljung, Karl R., Helsinki, kuoli taistelussa 2.4.1917 Ranska, 1914–15 Star, BWM, VM.

– Nelson Eric William, kuoli taistelussa 10.4.1917.

– Olin, Axel Alexand, kuoli taistelussa 21.2.1918.

– Pennanen, Alfred H. , Viipuri, kuoli taistelussa 17.7.1916 Ranska, 1914–15 Star, BWM, VM.

– Petersen, Charles, Finland, kuoli taistelussa 14.1.1918 Belgia, BWM, VM.

– Peterson, Mat H. ( äiti Tippo (Jeppossa?) kuoli haavoihin 5.7.1916 Ranska, BWM, VM.

– Petterssan, August S. , (isä Kiskasta, Orijärveltä) kuoli taistelussa 4.10.1917, Ypres, Belgia, BWM, VM.

– Piukkula, (Puikkula), Otto Valfrid Bruno, s. 1891, Turku , kuoli Sommen taistelussa 11.4.1918.

– Ravoline (Ravolaine, Ravolainen ( = Savolainen?)), David Sylvester , Mikkeli (Viipourin mlk), korpraali, kuoli taistelussa 24.7.1916, BWM, VM.

– Saarijärvi, Adolf, kuoli Englannissa 28.10.1918.

– Salonen Usko Leonard, s. 23.9.1889, Turku, korpraali, kuoli taistelussa 8.6.1917 Belgia (kaatunut 8.7,1917), BWM, VM.

– Savolainen, Arthur John, kuoli taistelussa 20.7.1916.

– Somero, Daniel, Yli-Kitka, kuoli taistelussa 4.10.1917 Ypres Belgia BWM, VM.

– Talava (Jalava), Ansselmi, (isä Turussa), kuoli taistelussa 23.8.1918 Ranska, BWM, VM.

– Tornroos (Törnoroos), Arvo Malakias, s. 1891, Rauma, merimies, naimaton, sotilas, kuoli taistelussa 5.10.1918, Ranska.

– Troyle (Turja?, mikä oli äidin nimi), Kontrat J., Turku, kuoli sotavankina 13.10.1918, Berliini, BWM, VM.

– Weckman, Walter Alen, kuoli Englannissa 9.11.1918.

– White, John H. , Viipuri, kuoli taistelussa 12.10.1917 Ypres, Belgia, BWM, VM.

– Wikström, Karl, Turku, kuoli haavoihin 17.8.1917 länsirintama Ranska, BWM, VM.

– Winter, Frank, kuoli Australiassa 12.9.1916.

– Wirta, Tobias Oscar, kuoli taistelussa 12.9.1916.

(Note on sources: The above information is summarized from an article (AUSTRALIAN JOUKOISSA SURMANSA SAANEET SUOMALAISET VUOSINA 1914–18 by Olavi Koivukangas) in “SUOMALAISET ENSIMMÄISESSÄ MAAILMANSODASSA – Venäjän, Saksan, Ison-Britannian, Ranskan, Australian, Uuden Seelannin, Etelä-Afrikan, Yhdysvaltain, Kanadan ja Neuvosto-Venäjän armeijoissa vuosina 1914–22 menehtyneet suomalaiset sekä sotaoloissa surmansa saaneet merimiehet” Lars Westerlund (toim.). ISBN 952-5354-48-2, Published by Edita Prima Oy, Helsinki 2004. Photos included in the text above are from the same source).

Finns in Australia – the Inter-war Years

A note on sources for this Post: There’s a book about the first 50 years of the Finnish Society in Sydney (Australia), published in 1979 – “Finnish Society of Sydney – 50 vuotta Värikästä Toimintaa” written by Satu Beverley. (For information, seehttp://finnsinsydney.org.au/). It’s available as a downloadable PDF file (Finnish language only, just in case you’re not Finnish) for anyone interested. This is the source used for much of the information below (although I have tweaked the Winter War Aid “a bit” in my alternative history), while a paper from the Journal of Baltic Studies, Volume 9, Issue 1, 1978, pages 66-72 entitled “Australian aid to Finland and the Winter War” by A.R.G. Griffiths (Flinders University of South Australia) forms the foundation for much of the political aspects of Aid to Finland by Australia (and many thanks to the Toronto Reference Library for having available this rather obscure Journal in all it’s issues and for copying the requested articles for me and providing them free of charge through the inter-library loan system. Gotta love libraries that keep all this obscure stuff and make it available at no cost – getting something tangible back for the taxes one pays is a real benefit).

Most of the Finns in Australia at the time of the Winter War had arrived in the 1920’s in the period after emigration to the United States became more difficult. As with North America, the majority of the Finnish immigrants to Australia came from the region of Ostrobothnia. One of the early arrivals was a Pastor Boijer, who arrived as a priest in Australia during World War I. He founded the Finnish Seamen’s Home and a Finnish Reading Room in a small apartment on Hamer Street in the Woolloomooloo district. This became a popular gathering place, especially since there it was possible to read Finnish newspapers.

In 1918, immediately after independence and the establishment of the Finnish Republic, Finland had established a consulate in Sydney. The first Finnish Consul in Sydney (and for Australia as a whole) was Kaarlo J Naukler. However, his term as Consul was short-lived as he died in 1921 (the inquest on his death was reported on May 21st, 1921 in an Australian newspaper, The Northern Advocate where it was disclosed that he had committed suicide. A doctor gave evidence that the deceased had come to him and said he had injected morphia into his leg because he was upset over his wife leaving him and asked if the Doctor could save him. The remedies tried proved unavailing. According to other evidence, Naukler had been overworking and was suffering from mental strain. The verdict was that death was caused by morphine willfully self-administered). A news report in the Sydney Morning Herald of 12 May 1921 reported that the body of Mr. Naukler was to be removed to Melbourne to be cremated, with the ashes to be brought back to Sydney, and afterwards be sent to Finland. The deceased had expressed a desire that his body should he cremated, and his widow was reported as observing his wishes. A Funeral Service was held at the parlours of Messrs. Wood Cofill Limited, George Street with the Rev. O. Schenk, of the Evangellical Lutheran Church, officiating. The service was attended by representatives of the Government, Military Forces, and Consular services. The Rev. Mr. Schenk delivered a short address, paying a tribute to Mr. Naukler’s public usefulness and private worth. There were present a full representation of the consular body and many representative citizens. During Naukler’s term, he apparently set up some sort of sports club for Finnish men.

His successor was Consul Harold Tanner, who in 1926 founded a local Finnish magazine. In those early years, the Finnish Consulate, apart from providing consular services, also played the role of a social club for the Australian Finnish community. In May of 1929, the Finnish Society of Sydney was founded by three women (Inga Lindblom, Aino Potinkara and Helvi Larsson) who were meeting in a coffee shop when one of them suggested founding a Finnish Society. The others agreed and they invited 10 more women to join in and a sewing circle was founded with membership consisting of the previously named women together with Elmi Lammi, Mimmi Tuomi, Martha Aflect, Helena Wirsu, Elmi Peltonen, Marja Koski, Margaret Klemola, Lyyli Muje and Ella Tanner, the wife of the consular representative. The number of members quickly grew to 19 and in November that same year men joined also and the Sydney Finnish Society was well underway. Gathering took place in the early days at home every other Friday. The presidents were all men from 1929 up to until 1983 when the first woman was chosen to be the president.

The Rev. Kalervo Kurkiala

In 1922, the same year as Consul Harold Tanner arrived, a new priest, the Rev. Kalervo Kurkiala, arrived to minister to the Finnish community in Sydney. The Rev. Kurkiala would go on to play an important role with the Australian Volunteer Force for Finland. Kurkiala was born on 16 November 1894 to Karl Johan Gabriel Groundstroem and Aina Fredrika Widbom (like many Swedish-Finns, he had changed his surname to a Finnish name). His brother was Jaeger (light infantry) Captain Ensio Groundstroem. In 1913 Kalervo Groundstroem graduated from the Helsinki Normal school, after which he studied at the Theological Faculty of the University of Helsinki from 1913 to 1915, gaining his degree. In the midst of WW1, Kurkiala left his theological studies and joined the 27th Jäger Battalion as a volunteer on 29 December 1915 where he was made a lieutenant. He fought in battles on the German Eastern Front on the Misa River, the Gulf of Riga and the Gauja. He married Elisabeth Rolfsin, a German woman, in 1918.

Kurkiala was influenced by a militarism that he thought beneficial to young men, including “country boys” as well as “bookworms and spoilt, sloppy idlers”. In his view, military training, besides preparing a person for the future, built muscle and character. In 1919 he wrote that military service can build an unshakable sense of duty in the individual. The barracks life, where many conscripts live close together, removes pettiness, selfishness and vanity. In another tract, however, he warns recruits of the dangers of barracks life. After the Finnish Civil War broke out, Kurkiala travelled to Vaasa, the White headquarters, and on 25 February 1918 was appointed Lieutenant. In March 1918 he was appointed a battalion commander in the White forces, taking part in the battles at Tampere, Lahti, Lyykylä, Mannikkala and Tali, where he was slightly wounded. He served with the General Staff from 3 June 1918 until he resigned from the army on 26 June 1919. He then resumed his theological studies and was ordained a minister in 1919. On 1 August 1919 he was ordered to take the post of pastor with the Central Finland Regiment and Häme cavalry regiment. He resigned from the Army again on 1 April 1920, and then studied philosophy and theology at the University of Greifswald in Germany from 1920 to 1921. On 1 August 1921 he was appointed pastor of the Jaeger Artillery Regiment. He held this position until 15 April 1922, at which time he again resigned and traveled to Australia, where he worked as chaplain at the Finnish Seamen’s Mission until 1926. It was at this time that he changed his surname from Groundstroem to the more Finnish-sounding Kurkiala.

Returning to Finland at the end of 1926, he was appointed Deputy Secretary of the Finnish Seamen’s Mission. In 1938 he was appointed secretary of the Finnish general ecclesiastical committee, a position he held until 1931. On 1 May 1931 he was appointed chaplain of Ikaalinen, and also worked as an English teacher in the Ikaalinen school from 1931 to 1938. He obtained a degree in doctrinal education in 1932 and was a member of the local military organization from 1934 to 1938. As an enthusiastic member of the Suojeluskuntas, he was among the first to take up the rapidly developing Finnish military martial art of KKT, and by 1938 was both a black belt, a sensei and a frequent writer on the subject of KKT in Finnish magazines and newspapers. On 1 May 1938 he was appointed Vicar of Hattula. As the threat from the USSR heightened in 1939, Kurkiala was asked to return to Australia with the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus Team travelling to Sydney. He accepted immediately and on arrival in Sydney, immediately commenced renewing old ties. Fluent in English as well as German, Swedish and Finnish, he spoke at many Church gatherings around New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia as well as at numerous meetings organized by the Australian Finland Assistance Organization, a group jointly chaired by Dr. Lewis W. Nott (more on Dr. Nott later) and Colonel Eric Campbell.

The success of this group and others in influencing the Australian Government to permit and support the raising of Volunteer Units to be sent to Finland owed much to Kurkialas’ speeches. He was a popular speaker and much admired for his ability to sum up the issues clearly and succinctly, as well as for his oft-stated intention of returning to Finland to fight alongside the Australian Volunteers. He would in fact accompany the Australian Volunteers on board ship to Finland. Appointed Liaison Officer to the Australian Volunteers, he spent his time en-route to Finland with the volunteers training Australian Officers and NCOs on the Finnish military, conducting lectures to the men on Finland and holding Sunday services. No stranger to combat himself, he also introduced the Australians to the Finnish martial art of KKT, of which he was both an enthusiastic practitioner and sensei. Extremely popular with the Australians and a strong believer in martial Christianity, he would remain with the Commonwealth Division and fight with the Australians for the duration of the Winter War, taking part in the battles on the Karelian Isthmus and later on the Syvari Front. The Commonwealth Divisional CO would appoint Kurkiala a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Australian Army.

Finnish Liaison Officer to the Commonwealth Division and Military Chaplain, Lieutenant-Colonel Kalervo Kurkiala making a memorial speech to fallen Australian brothers-in-arms in late 1940

Kurkiala would remain with the Australians after the end of the Winter War, volunteering to accompany the Volunteers to the Middle East where he retained his rank in the Australian Army and was appointed Military Chaplain with the Australian 17th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Stanley Savige, one of the two Australian Brigade Commanders in Finland. With the Australians in the Middle East, he would continue to promote KKT enthusiastically, passing in his skills to many Australian soldiers. He would return to Finland in early 1944 as Finnish Liaison Officer with the Australian Division that would fight with the Maavoimat for the remainder of WW2.

Kurkiala would remain with the Australians after the end of the Winter War, volunteering to accompany the Volunteers to the Middle East where he retained his rank in the Australian Army and was appointed Military Chaplain with the Australian 17th Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Stanley Savige, one of the two Australian Brigade Commanders in Finland. With the Australians in the Middle East, he would continue to promote KKT enthusiastically, passing in his skills to many Australian soldiers. He would return to Finland in early 1944 as Finnish Liaison Officer with the Australian Division that would fight with the Maavoimat for the remainder of WW2.

After the war Kurkiala and his family immigrated to Australia, where he worked as a primary school teacher until 1947, when he became a teacher of religion and philosophy at Knox Grammar School, NSW. In 1950 he was appointed Vicar of St John’s Estonian and Finnish Lutheran Parish of Sydney, a position he held until he retired in 1964. Also in 1950, he was elected Chairman of the Australian Winter War Veterans Association, a position he held until 1960, after which he stood down. Kalervo Kukkiala died on 26 December 1966. He was buried in Sydney, Australia. Iivari Rämä’s biography of Kalervo Kurkiala, “Jääkäripapin Pitkä Marssi” (The Jäger Priest’s Long March) was published in 1994.

Returning to the Finnish Community in Sydney

Another Finn in Sydney, Karl Selvinen rented an old house at 48 Arthur Street, Surry Hills, part of the city, and in 1929, established a boarding house called “Suomi Koti” (Finland Home), mainly for mariners. The reading room at the Consulate was transferred to Suomu Koti, as was a library from the Consulate. For Finns in Sydney, Suomi Koti now became Sydney’s general place of assembly. The Finnish Society met there from 15 November 1929. The gatherings also came to include men such as Karl Selvinen, James Aalto, August Lammi and Lillqvist. The Finnish Society of Sydney had now begun. Rules for the Society were drawn up and with the assistance of a Finnish sailor, printed in Melbourne. These Rules stayed in effect for more than 20 years, until 1964 when the club changed its name to the Sydney Finnish Club.

“Suomi Koti” and the official opening of the Independence Day of December 1929. The presence of about 70 people, including. Wirsu, Laukka, Consul Tanner, his wife, Mrs. and Mr. Lammi, Hill, Selvinen, Raninen, Walton, Muje, Lillqvist, Pohjanpalo, Huhtala, Mrs. and Mr. Tuomi, Orava, Mr. and Mrs. Tulander, Aalto, Laherholm, Westburke. This photo was published in the Sydney Daily Telegraph 9 December 1929

The founding meeting of the Sydney Finnish Society of 15 November 1929. Approximately 80 people were present, among them. Consul Harald Tanner and his wife Ella, Potinkara, Snellman, Toppinen, Loukola, Väisänen, the Hoipon brothers, Lagerholm, Walton, “Helsingin Oskari” (Helsinki Oscar), Aalto, Wallie, Peltomaa, Adamson, Halonen, Gustavson, and Selvinen.

The Finnish Society benefited greatly from the warm-hearted support of the Consul H. Tanner and his wife. Mr. Jorma Pohjanpalon was a regular presence at the Society’s meetings, always sitting at the piano and playing folk songs, polkas and waltzes, etc. A number of the other men also played Finnish music, including Josef Kaartinen on the saxophone, Eric Bergen on his hanurinsoittaja (piano accordion) and Bruno Emelaeus with his violin. Just when the club was getting a good start, the financial depression began to have an effect. Industrial plants were closed down, construction work came to an end and Finnish men began to seek out of town employment, many of them in the Gosford region, which later became a very Finnish community. One of the first Finns in the Gosford region was August Lammi Kauhava, whose Apple Orchard was in 1980 the largest Finnish-owned farm in the locality. Men and women gradually moved out to the country and in the city were left only a few families, women working as maids and a few more or less unemployed young men. All of this adversely affected the club’s activities and also the business of Suomi Koti.

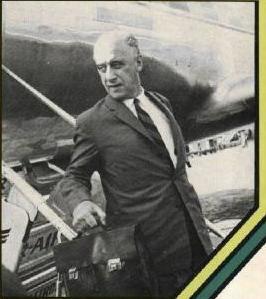

Jorma Pohjanpalo was born in Ylivieska, in Ostrobothnia. After completing business school, where he studied economics, he was Secretary at the Finnish Consulate in Sydney from 1927-31. During this period he acquired what would be a lifelong interest in Finnish migration. Following his return to Finland he published a book based on his experiences entit;ed “Australia by Pen and Camera.” He would return to Australia in October 1939 to work as part of the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team in Sydney.

Post WW2, Professor Pohjanpalo served on many committees and was for many years on the Executive Board of Suomi-Seura. When the Institute of Migration was established in 1974, Jorma Pohjanpalo as appointed as the Suomi-Seura delegate on the Institute’s Council and was elected as the first council chairman. Having served in this capacity from 1974-1984, Professor Pohjanpalo was then elected as the Institute’s first Honorary President. He supported the Institute’s work in many different ways, on his journey’s to different parts of the world, and by donating materials linked to migration, including writings, photographes, etc., to the Institute’s Archives. (Photo taken on his 80th birthday on 12.12.1985). He published several books on shipping and plastics.

When at last the economic situation started to improve, Karl Selvinen, handed over the lease for Suomen Koti to two Finnish ladies, Inga Lindblom and May Mclntosh. When both of these ladies married a couple of years later, the home ceased to be a gathering place for Finns. From then on, the Club had no permanent meeting place. When the new Consul, Paavo Simelius and his wife arrived from Finland in 1935, their spacious home became the new gathering place. Many festive occasions were held there and Society meetings were often held at the Finnish Consulate’s reading room on Saturdays, hosted by the new Consul.Many good memories remained of these events. The Finnish Society of Sydney’s founding members, James Aalto, and Mimmi Tuomi, later reminisced about those early days. Jormi Pohjanpalon was a lunatic on the piano, Josef Kaasalainen was a professional saxophone player and Sylvia Aalto often sang solo songs. On social occasions, members performed their own events, and no paid performers were ever needed. The atmosphere was intimate, as the number of Finns in Sydney was small and all knew each other well.

Many of the events were attended by 70-100 members even before World War II with guests coming from all over – including from Newcastle, Albion Park, Wollongong and the Gosford area. Alcohol was not drunk at the public meetings – in the old Finnish tradition, members brought alcohol with them and stashed it “just around the corner” to drink. For dances, the entrance fee included a cup of coffee and sandwiches, which the hostesses brought to the table. All members, including officers, paid the entrance fee. This remained unchanged until the late 1950s. The Society intended only to cover the running costs and not make money.

From the beginning, activities included meetings, dances and picnics. The first picnic was held the day after the inaugural event. Popular picnic spots were the beaches, especially at Dee Why beach, which was then a totally uninhabited beach. Centennial Park and Maroubra were also popular. James Aalto also remembers with joy the dances. These were held in the house over the liquor cellars, where a “fishing line” was dropped into the cellar and the “catch” was hauled up. In the early days life was good. Politics and religion did not intrude into the activities of the Society. Mrs. Ida Niemi remembers how in the opening ceremony of the Society it was very clearly said that we are all Finnish and class differences among immigrants do not exist. All members eagerly participated in the club and were prepared to assist in dances, gatherings and performances. The needy were also assisted. Times were tougher back then and while help was forthcoming from the government, it was not much – and the Finnish people were strangers in Australian society, which in its own way was rather insular. Under these circumstances, the club activities were of great importance to the small group of Finnish immigrants in Australia.

Australian Finns outside of Sydney

Note on Sources: Some of the below is sourced from an article, “Suomalaiset Australiassa” by Olavi Koivukangas, Professori, Siirtolaisuusinstituutin Migrationsinstitutet, Turku – Åbo 2005. More detailed information on Finns in Queensland is sourced fromhttp://freepages.history.rootsweb.ances … he%20Finns while information on Nestori Karhula is sourced from Wikipedia.fi (photographs from http://www.migrationinstitute.fi ) for providing the initial information that led me to include this. Almost all of the photos in this post are sourced from the Finnish Migration Institute – http://www.migrationinstitute.fi – which has a great collection of photos on Finns in Australia. I’ve also referred to chapters in a book entitled “Tyranny of Distance: Finns in Australia before the second World War”, also by Olavi Koivukangas.

We’ve already covered some information on Finns in Sydney and Finnish Australians in WW1 – but Finnish connections to Australia extend far into the past. When Captain James Cook, the British explorer who mapped Australia for the Royal Navy, landed at Botany Bay in Sydney around, a native of Turku, Herman Spöring was part of the scientific group on the Endeavour. Spöring died of fever in the Java Sea in January 1771 as the Endeavor was returning to Britain and was buried at sea, but many of Spöring’s illustrations remain in the British Museum in London. Captain Cook had earlier shown his appreciation of Spöring’s work by naming an island in New Zealand after him (Spöring, or Pourewa, Island – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pourewa_Island). Cook was also apparently grateful to Spöring for repairing a quadrant that some Tahitians had stolen and broken. Canberra (the capital of Australia) has a street named after Spöring and in 1990 a memorial was erected in Turku ((Åbo), Spöring’s birthplace. The memorial includes a rock taken from Pourewa (Spöring) Island, commemorating the first Finn to set foot in New Zealand in 1769. The Finnish Federation of Australia Association has also set up the Spöring Fund, which supports Finnish-Australian cultural exchanges.

After the United States and Canada, Australia has been the next most popular destination for Finnish migrants. The Finnish emigration of some 361,000 persons to the United States and Canada over the last half of the nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth was part of the enormous migratory movement in which over 55 million Europeans left their homelands for overseas countries between the Napoleonic wars and about 1930. In this mass migration, Australia was not a popular choice. Travelling the vast distance between far northern Finland and the antipodean world of the Southern Seas in a period when a voyage around Africa or South America took months, was costly, and often dangerous. The strongest brake on Australia’s population growth was its distance from Europe. When European overseas mass emigration started in the first half of the nineteenth century, a working family in Britain was not easily attracted to Australia. The sea voyage was much shorter, safer and three or four times cheaper to New York than to Sydney. Moreover, during the long voyage to Australia, a working man was compulsorily unemployed for months. And if he eventually decided to return from Australia, he had only a faint prospect of being able to pay his passage back to Europe. The disadvantages of isolation eliminated Australia as a goal for most emigrants who had to pay their own fare.

While Australia attracted few working men until the late 1820s, it could attract men of capital by offering free land and convict labourers. The problem of attracting working people to Australia was therefore crucial. A way of paying the fares had to be found. In line with the ideas advanced by Edward G. Wakefield, a bounty system was introduced in the 1830s allowing private employers to select migrants and to receive a government bounty for each approved person landed. Others came through direct government assistance. The source of money was the vast expanses of land owned by the crown. Discovery of gold in eastern Australia in 1851 brought a large influx of immigrants, including Germans, Scandinavians, Chinese and Americans. By 1860, the Australian population had grown to 1,145,000, three-quarters from immigration. About 40 per cent of the immigrants were assisted. Owing to the gold and free labour, the transportation of convicts ended. By the end of the 1880s, assisted immigration had been virtually abandoned by all the colonies except Queensland and Western Australia. Around 1900 a policy of virtual exclusion of non-European migrants was adopted—this policy remaining essentially unchanged until after the Second World War. In the years preceding World War One, Australia experienced extensive immigration, especially after 1906, and this continued until the war halted immigration. About 187,000 assisted settlers arrived in this period.

There is no record of the first Finn to settle in Australia, but more than likely he was a sailor who jumped ship from one of the thousands of sailing ships that visited Australia. In 1874 for example, there were likely to be at any one time 4 to 5 Finnish ships in Sydney. Even up until WW2, Finnish sailing ships from the Åland-based Gustaf Erikson line transporting wheat from Australia to Europe were often to be found (as we have covered in an earlier post) in Australian ports. In 1851, news of the rich gold discoveries in Australia spread quickly and sailors and miners from the California gold fields were the first to respond. It is estimated that about 200 Finns tried their luck in the Victorian and New South Wales gold fields. Some of them stayed permanently in Australia, others continued the search for gold in New Zealand and some returned to Finland.

The Barque “Basset” – it was on sailing ships like this that the first Finnish immigrants came – generally seamen who left their ships in Australia and stayed…

Thousands of Finnish seamen sailed under foreign flags, especially in British and American ships, and these vessels whaling and sealing in Australian and New Zealand waters after 1788 generally had crews of highly mixed national origin. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Finnish ships also began to visit Australian ports. Before gold was discovered in Australia in 1851, a 23-year-old seaman, Isak Herman Sandberg, from Kaskinen, Finland, landed there in January 1851 from the Bombay, sailing via London. When he was naturalized fifty years later, he was living in Victoria and gave his occupation as laborer. As the news about the rich Australian gold discoveries did not reach Europe before the second half of the year 1851, there must have been some other reason for Sandberg’s staying in Australia. Assuming that only a minor part of the early Finns in Australia were eventually naturalized, there probably were but few Finns among the 400,000 inhabitants of Australia in 1851, although next to nothing is known about these early settlers.

When gold was discovered in eastern Australia in 1851, tales of fabulous fortunes made in Australian goldfields spread rapidly all over the world, causing the first major influx of non-Britishers to the Australian colonies. Thousands of men started to cross the oceans to Australia. Over 600,000 immigrants arrived and the four colonies grew to six as Victoria and Queensland cut loose from New South Wales. Another feature was the inflow of seamen deserting their ships in Melbourne and Sydney in response to the lure of the goldfields. In the first week of 1852, only three of the thirty-five foreign ships in the bay at Melbourne had full crews. Often the whole crew, including the captain, deserted their ship. The Australian gold discovery of 1851 must be seen in connection with the California gold rush of 1848. It was in 1849 that the first Finnish sailors jumped ship to follow the crowds to the goldfields. It has been estimated that California gold drew over two hundred Finns, who settled on the Pacific coast. Many returned to San Francisco with empty pockets and from there, with the strong demand for sailors, the Finns could ship out to Europe—or to Australia—for reasonably good wages. One Finnish fortune-seeker was Isaac Mattson, a native of Turku, who travelled from San Francisco to Sydney in 1852. He proceeded to the rich Ballarat goldfield in Victoria and spent seven years there. Then he went to Tasmania, presumably on a similar quest, and after staying there for thirty years, moved on to New South Wales and then to New Zealand before living out his last years in Melbourne. When he was naturalized there in 1911, nearly sixty years after his arrival, he gave as his occupation “mine carpenter” and went on record as a widower with four children. Isaac Mattson’s life reveals the great mobility of the early Finnish settlers in Australia.

There were also Finns among the gold miners who left the fields after a few years. Two brothers, Alfred and Wilhelm Haggblom, natives of Isojoki, Finland, were sea captains who spent four years in the goldfields in Victoria and New South Wales and returned to the Old Country in 1858. In Australian naturalization records, there are listed fifty-one Finnish settlers who arrived in the “golden decades” of the 1850s and 1860s. Assuming that of these early immigrants every fourth became naturalized, the number of Finnish settlers that landed in Australia in 1851-69 was approximately two hundred. How many left Australia to return to the land of their birth, to move to other countries, or to go back to sea is difficult to estimate. A rough estimate of the number departing could be every second or third. The Finns in the Australia of the gold rush after the middle of the nineteenth century numbered only a couple of hundred; and they were often counted—especially the Swedish-speaking Finns—as belonging to the larger Scandinavian group, some 5,000 strong. These numbers also include seamen employed in Australian coastal waters, labourers in seaports, artisans, etc., many of whom, perhaps, had first tried their luck searching for gold.

The major influx of Finns to pre-Second World War Australia took place in three waves: in the 1880s, in the years preceding the First World War, and again in the 1920s. The first peak can best be called the seaman immigration, when Finnish deep-sea sailing vessels and other ships with Finns in the crew put into Australian ports. With the growth of its population and its wheat and wool production, Australia held out attractive opportunities for Finnish seamen to sail with the Australian coastal fleet or work on the wharves of rapidly growing Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide, or even in inland mining towns. The number of these mobile Finns in the 1880s may have been somewhere up to 1,000—almost all males. In the depression years of 1890-1906, Australia did not attract many Finns.

The Utopian Commune of Matti Kurikan

The peak of Finnish migration to the United States was in the early 1900’s, culminating in 1902 when 23,000 Finns took ship to America. However, at the turn of the century Australia was trying to attract immigrants from Britain – and when enough British immigrants could not be found, the Queensland State Government offered free passage to migrants from Scandinavia. Over 1899 and 1900, when the travel grants was in force, some 200 Finns settled in Queensland over a period of around 10 months. Of these 200, 78 were members of a group led by Matti Kurikka (24 January 1863, Tuutari, Ingria – 4 October1915 Rhode Island, USA, a writer, journalist, leader of the labor movement and utopian socialist) dedicated to setting up a utopian settlement. The Kalevalan Kansa Society was founded in Helsinki in 1899 with the aim of establishing a Finnish utopian socialist settlement in Australia. Kurikka arrived in Brisbane in October 1899, after which his supporters soon began to arrive. The settlement was not successful, and Kurikka moved on to Canada in 1900, together with many of his supporters, to set up the rather more successful “Sointula” community in British Columbia.

Kurikka was the editor of the Työmies newspaper from 1897–1899. In 1908 Kurikka purchased the Wiipurin Sanomat. As editor of Wiipurin Sanomat, Kurikka was initially influenced by the Young Finns political movement, later moving towards Christian socialism. Kurikka moved to North America in the year 1900 and founded the newspaper Aika, the first Finnish-Canadian newspaper. In 1901 Kurikka helped establish Sointula, a utopian island colony on Malcolm Island, British Columbia based on cooperative principles. Sointula dissolved as a utopian colony in 1905 after financial difficulties and a devastating fire, but continued as a fishing and logging based community.

However, many of Kurikka’s supporters remained in Queensland and settled in the Nambour area, 100km from Brisbane, where they moved into sugar cane cultivation. The Finnish colony in this area came to be called Finnbury, where a Finnish immigrant society, “Erakko”, provided a hand-written magazine called “Orpo” (“The Orphan”) for the small Finnish community which felt somewhat isolated in a foreign country and culture. In general however, the early Finnish immigrants in Australia were seamen and labourers, a mobile group who were not disposed to establish societies or clubs. Another factor militating against a more active social life was the small number of women. The most common meeting place for Finns in Australia — as for many other nationalities — was the local hotel or pub, where fellow countrymen could be met and news heard.

It was only at the turn of the century, when the first groups of Finnish farming settlers appeared in Queensland, were any Finnish societies founded. Perhaps the first of these was the socialistic-minded Nambour settlement mentioned above. A Finnish society was founded in Brisbane in 1914 and another in Melbourne in 1916. When, in the first half of the 1920s, as Finns began to arrive in the sugarcane fields of northern Queensland, a society was formed by some 150 Finns around their leader, Nestori Karhula, a former officer in the Finnish army. It arranged picnics and athletic meetings, tried to establish a library and even arranged to run a course in the English language. This compact Finnish community dispersed after Karhula left for Brisbane in 1926.

After the USA introduced immigration restrictions, another 1,000 Finns diverted to Australia, most finding employment in the sugar cane fields of Queensland. Some of these Finns acquired farms around Nambour, Bli Blistä. Nambour itself had had an active Finnish Association since 1915, of which a central part was the Sports Club. Former members of the commune established by Matti Kurikan were active members of the Association and to this day, descendants of Finnish immigrants live in the area, forming one of the largest enclaves of Finns outside Sydney and Newcastle. Finnish immigrants also moved to Mullumbimby where, post WW1, they built another large enclave of Finns. By the 1930s they were amongst the largest immigrant groups in the district. Those who lived in this banana-growing area came mainly from the Swedish-speaking communities of the north-west coast, while New South Wales’ next largest Finnish enclave at Gosford was predominately Finnish speaking.

Suomalaisia keininhakkuussa Innisfailissa. Nambour, Qld./ Finnish sugar cane farmers, Nambour, Queensland

Elsewhere, another Swedish-Finn, Karl Johan (aka Jacky) Back, led the Finnish invasion of Mullum in 1902. He was of Swedish descent, born in Munsala (Ostrobothnia) under the old family name of Ohls in 1877, and migrated to Australia in 1899 to slip the conscription agents of the Russian Czar. Probably with stake money provided by his father, he acquired three blocks (640, 510 and 22 acres) at Goonengerry and shortly afterwards started construction of a sawmill on the smallest block, Devil’s Lookout, adjacent to which his brother, William Andrew (Vilhem Anderson), and his father, Andrew William, acquired respectively 442 and 65 acre blocks shortly afterwards. The mill was a massive undertaking, but it never got operational and the huge hardwood logs stood on the skyline for about 40 years until a bushfire destroyed the place. (In 1999 the farm blocks became the main portion of the Goonengerry National Park.)

Cutting and moving timber for Sawmilling, Queensland. 1923-1928. Finnish immigrants tended to move into work they were familiar with from the home country – timber-felling, sawmilling, farming….

“Jacky” Back’s father Anders, and his 16yr old brother, Vilhelm (“Billy”) arrived at Bangalow Station in early 1903 in the middle of a heat wave. The story goes that they walked through the Big Scrub all the way to Goonengerry, with Anders dressed in fur-lined clothes suitable for the arctic winter, having been attacked along the way by hundreds of leeches dropping from the trees. Whether it was this experience, or snakes and other nasties, unheard of in Finland, that turned him off the promised land is unknown, but Anders Back promptly returned to Finland and left his sons to get on with the job on their own. He is however believed to have been a man-of-means in Finland and to have made another trip out to Australia at some stage. A short time later “Jacky” and “Billy” made their way along the bullockies’ tracks to Wilson’s Creek where Jacky became the pioneer sawmiller on site. After a swag of surrounding scrub had been felled and burnt and all the stumps removed he diversified into farming and market gardening. Billy meanwhile had branched out on his own and established a farm at Burringbar, having mortgaged his Goonengerry block to the NSW State Savings Bank. He won the hand of Miss Christina Hart in 1908 and subsequently was credited with driving the first motorcar over the tracks to Wilson’s Creek to visit his in-laws. Upon settling in Mullum he became an elder and keen worker for the Presbyterian Church.

Jacky, a backwoods philosopher, has the distinction of being the first Finnish author in Australia, a remarkable feat for a bloke who never had a day’s schooling in the English language in his life. Using the pseudonym “Australianus”, he wrote a book of verse and stories called “The Royal Toast”, of which he had several hundred printed. He also wrote a book on economics and contributed articles to the Sydney Bulletin. In the middle of the Depression he tried to save the world with his book “A Solution to the World’s Financial Problems”, published in 1932. He gained a reputation as an eccentric and colourful character who could turn his hand to anything. He seems to have become a banana grower at Yelgun sometime in the 1930s before retiring to live with his Holm relatives at Billinudgel. He died in 1962 aged 84 and lies in Mullum cemetery.

As for “Billy”, the Tweed Times and Brunswick Advocate was prescient in early 1909: “Mr W. Back of Burringbar was offered by auction at Burringbar £16 per acre for his farm of 296 acres… and he …owns over 1000 acres of prime land along the railway line and 1280 acres at Mullumbimby. As Mr. Back is a very young man, there must be looming in front of him the vision of a millionaire’s wealth. His Burringbar farm supplied the poles for the Lismore to Casino telephone line.” He went on to become a mover and shaker in the business world – Beyond doubt the wealthiest Finnish immigrant in Australia. Just before the war he left Burringbar and settled in Mullum where, in 1918, he built “Cedarholm” with cedar milled by his brother Jacky. In Mullum he became an auctioneer and stock and station agent and began buying up large properties and subdividing, including “Jasper Hall” at Rosebank and “Morrison Farm” fronting the Brunswick, which took up about a quarter of the Mullum municipality. He is credited with building 100 houses in Mullum and creating 30 dairy farms. Later he moved into Queensland and acquired a large station at Winton, amongst others, before developing the suburb of St Lucia in Brisbane. Sydney properties were also in the portfolio. Through the 1930s and 40s his real estate company was the leading broker of banana plantations, but the growth of his Queensland business interests forced a move to Brisbane in the late 1940s. Both he and Christina died in Brisbane (he in 1974 aged 87 and she in 1970 aged 83) but are buried in the Mullum cemetery.

The Back brothers sister Anna (Mrs Erik J. Holm (Nyholm), landed with her husband and five children in 1921. They lived and worked at Main Arm for 6yrs before acquiring a 275 acre farm at Billinudgel where they remained until 1968. Another sister, Sofia, remained in Finland, where their father Anders died in 1928 and their mother, Sanna in 1937. That such remote deaths in Finland should be reported in the Tweed Daily (the local newspaper) suggests the local prominence of Billy Back at that time. Billy Back certainly had pull. During WW1 it wasn’t safe to speak with any sort of a non-Australian or non-British accent in Mullum and in mid 1915 the Star found it necessary to say “It has been said that Mr. W. Back of this town is of German nationality. On Mr Back’s naturalization papers, 18 Feb1908, the place of birth is given as Munsala, Finland, a Swedish part.” The next paragraph continued in the same vein: “Mr E. J. Erichs, a native of Denmark….” But no such consideration was given to other aliens, who had to pay for their own adverts.

The Backs also acted as the nucleus for the chain migration of their compatriots from Finland. Their father Anders no doubt passed the word around of the success of his sons in Australia and “Billy’s” holiday back home in 1923/24 generated much interest. Some of those who followed the Backs include the Kastren, Holmkvist, Holmnas, Fors, Melen, Tuohimaki, Roos, Snabb and Soderholm families. (Possibly connected to the farming Soderholms was Captain Soderholm, the Finnish Master of the ‘SS Bonalbo’ doing regular runs between Ballina and Sydney through to the early 1930s.) The Back farm at Wilsons Creek was the staging post for Finns proceeding into Queensland, particularly those making for the Finnish Commune at Nambour. The Backs were followed by other migrants from Swedish-speaking Finland, including members of their own family. The Finnish community at Mullumbimby grew during the 1920s… and became firmly established during the 1930s. Billy Back’s farms were also the initial source of employment for many new arrivals who later moved on to north Queensland.

Aksel Rönnlundin (kuvassa taustalla) perhettä ja työmiehiä Nambourissa. Edessä maatyömies ja Orpo-lehden toimittaja I. O. Peurala. /Aksel Rönnlund (in the background) and the family of the laborers – Nambour. Maatyömies front and Orpo journalist I.O. Peurala.

A number of these new arrivals were men who had fought on the “White” side in the Finnish Civil War. In all, it seems that around a dozen “white” infantryman went to Australia in the 1920s, preferring to emigrate to Australia rather than Canada – especially as many of the Canadian Loggers were on the so-called red side. But Australia was also preferred over Canada due to the economic and climatic aspects – if the travel money could be acquired from somewhere. One of these young men was Antti Isotalo, great-grandson of Antin Isotalo, who later returned to Finland. Another such was Nestori Karhula, the driving force behind the Cairns Finnish Community, who arrived in 1921. Karhula was one of a number of young Ostrobothnian men who began to arrive in groups in the early 1920’s.

Nestori Karhula – Jaeger Lieutenant and Volunteer in the Winter War

Nestori Ilmari Karhula (9 November 1893 Lohtaja – 13 January 1971 Brisbane Australia) was a infantry lieutenant in the Finnish Jaegers, later emigrated to Australia and returned to Finland with the Australian Volunteers to fight in the Winter War. His parents were farmers, Tuomas Karhula and Mariana Huhtala and Nestori himself married in 1920 to Kerttu Wäggin. Nestori Karhula graduated from high school in Kokkola in 1913 and joined the South Ostrobothnian Students’ Association. He continued his studies at the University of Helsinki in the Faculty of the Philosophy Department and in agricultural economics between 1914-1915. In 1915 Karhula travelled to Germany as a volunteer soldier where he underwent infantry training in the 27th Jaeger Regiment. He took part in the fighting on the Eastern Front at the Misse River, the Gulf of Riga and the Aa River.

Karhula returned to Finland on 8 December 1917 and joined the White Army where he took part in the preparation for the Civil War by training Suojeluskuntas members in Oulu. He was also involved in the transfer of arms from Kokkola to Oulu in January 1918. After the beginning of military operations, he led the capture of Kokkola. Under his command were assembled Suojeluskuntas units from Kaustinen, Vetelin, Esse, Terjärv and Kokkola, as well as the rural Guards. After the capture of Kokkola, he used his frontline experience to train the troops. Karhula eventually transferred to the Jaeger troops and was made first commander of 7 jääkäripataljoonaan, then on 2 April 1918 to Konekiväärikomppaniaan Light Infantry Regiment, and on 20 April 1918 company commander 4 Jaeger Battalion konekiväärikomppaniaan. He took part in the Civil War battles at Tampere, Tarpilassa and Raivola.

Karhula served after the Civil War as a machine gun company commander in the 2nd Jaeger Regiment, and later in the Pori infantry regiment No. 2 He resigned from the Army in 2 September 1918 and moved to the Civil Guards where he was as the local head of the Lohtaja Kokkola Civil Guards. He was transferred on 1 May 1919 to be local head of the Central Ostrobothnia Suojeluskuntapiiriin, from which he was transferred on 10 February 1921 to be the Lohtaja Guard local commander. In 1921 he left Lohtaja to emigrate to Australia, where he worked as a farmer in Queensland.

Keskellä Nestori Karhula. Cairns District, Qld. Joulukuu 1923 – “Crocodile” Karhula (standing in the middle of the group), Cairns District, Queensland, Australia, December 1923

Suomi-farmi (Redlynch lähellä Cairnsia), Queenslandissa. Oikealla jääkäriluutnantti Nestori Karhula, Kerttu Karhula ja tytär Toini. 1920-luku / Suomi-Farm (at Redlynch, near Cairns), Queensland. On the right, ex-Jaeger infantry lieutenant Nestori Karhula, his wife Kerttu Karhula and their daughter Toini. 1920s.

ääkäriluutnantti Nestori Karhula tyttärensä Toinin kanssa Väinö Ojalan haudalla. Redlynch. 1920-luku / Jaeger Lieutenant Nestori Karhula daughter Toini with Väinö Ojala’s grave. Redlynch. The 1920s

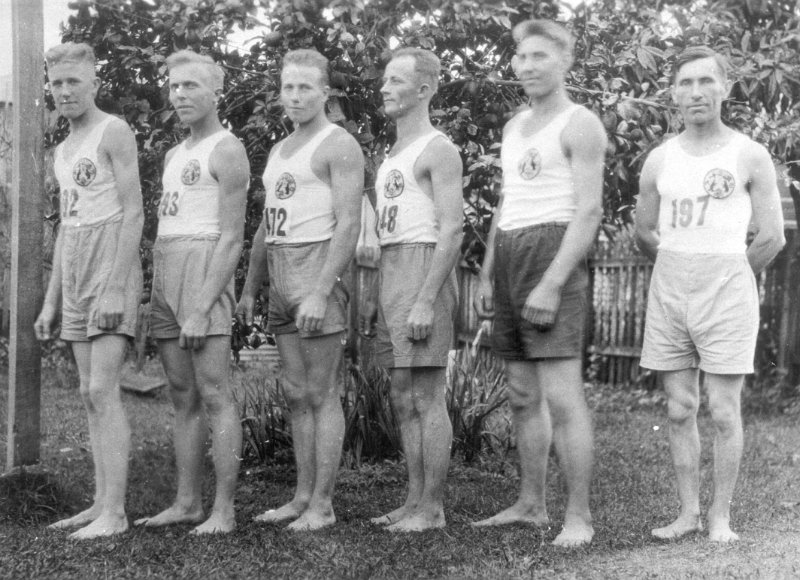

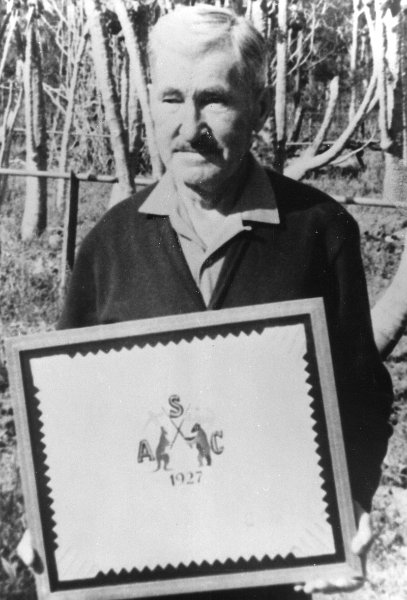

In Queensland he also became a Justice of Peace), in 1925 he helped establish the local Finnish magazine. He was also interested in the old Australian and New Zealand Finnish and in 1923 he founded the Cairns Finland Society. In 1927 he also founded the Suomen Athletic Club in Brisbane. Karhula was Secretary on the the Eight Mile Plains Elementary School Committee in 1927-1928 and the Secretary to the Mt. Grovattin School Committee in 1929-1931, as well as Runcovrin Progress Association secretary from 1929 to 1932. Karhula was also a member of the local air defense (Australian Air Force Reserves perhaps?).

Like almost all Australian-Finns, Karhula was actively involved in local Finnish Association and Finnish community activities as well as in wider community activities. He was also well acquainted with the previous Finnish Consul, Harald Tanner as well as with the new Consul, Paavo Simelius. As the threat of war between the USSR and Finland loomed, Karhula was heavily involved with the work of the Finnish Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team as they planned and worked to garner Australian support for Finland. As an ex-Army officer, and one with considerable experience in both the First World War and the Finnish Civil War, as well as being well-acquainted with the Finnish Consul, Harald Tanner, and well-established in the local community in Queensland, Karhula was consulted frequently.

Suomi Athletic Clubin edustajia 1920-luvulla. Vasemmalta: Reino Ruhanen, Aimo Sulkava, Matti Takala, Niilo Klemola, tuntematon ja Nestori Karhula / Finnish Athletic Club members in the 1920’s. from left: Reino Ruhanen, Aimo Sulkava, Matti Takala, Niilo Klemola, unknown and Nestori Karhula

Lindströmin farmilla. 1931. Vasemmalla konsuli Tanner, Mr & Mrs W.Lindström, Jussi Tilus, Mrs Karhula (istuu), Mrs Tanner ja Nestori Karhula / At Lindström’s farm in 1931. On the left, Finnish Consul Harald Tanner, Mr & Mrs W.Lindström, Jussi Tilus, Mrs. Karhula (sitting), Mrs. Tanner and Nestori Karhula

Nestori Karhula esittelee perustamansa Suomi Athletic Clubin tunnusmerkkiä / Nestori Karhula presents founder Finland Athletic Club emblem

As the threat of war between the USSR and Finland loomed, Karhula at first planned to raise a company of Australian-Finnish Volunteers to travel back to Finland to fight in the Winter War as part of the Finnish Army – and by early December 1939, some 150 Australian-Finns had committed to join this unit. However, as the wave of Australian support to send a large contingent of Australian Volunteers turned into a solid commitment from the Australian Government in early January 1940, Karhula and his Company of Australian-Finns were subsumed into the overall Australian unit.

Their ability to speak Finnish as well as the Australian version of English, and the fact that a number of them were familiar with the Finnish Army, led to the Australian-Finns being attached to the Australian Volunteer Units as liaison officers. This ensured that every Australian Unit within the volunteers had a number of fluent Finnish-speakers attached. On arrival in Finland, as the different components of the Commonwealth Division came together, the Australian Finns were farmed out across the entire Division, thus ensuring at least a modicum of communication with Finnish units was possible.