Australian Aid to Finland

As we know, Australia sent two full Infantry Battalions of volunteers to Finland for the Winter War together with sufficient volunteers to form supporting units for what would become the Commonwealth Division, a Divisional-sized Field Hospital, Medical personnel and Ambulance Units sufficient to support three Brigades. Australia was also instrumental in sending the personnel for a composite New Zealand / Australian Field Regiment (of Artillery). Finally, Australia (with some limited contributions of personnel from New Zealand and South Africa) would also send sufficient military personnel to establish two Brigade Headquarters units (Canada provided personnel for a third) together with the personnel for the Headquarters units of the “Commonwealth Division” that Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Rhodesia and Canada would jointly agree to forming from the disparate collection of volunteer units dispatched to Finland from within the British Commonwealth. Australian Aid to Finland over the course of the Winter War was significant for a small country on the other side of the world.

Australia would not forget Finland after the Winter War – as well as ongoing shipments throughout WW2 of large quantities of grain, mutton, kangaroo tails and wool for uniforms (albeit on ships of the Finnish merchant marine) – and in 1944, Australia would send a full Infantry Division (as would New Zealand) to fight with the Finns against Germany. While herself short of military equipment and unable to provide weapons and munitions to Finland in the Winter War, Australia would, with New Zealand, also pay for a number of artillery pieces and shells from the UK to be sent to Finland. Australia would also ship a considerable number of Ford Trucks to Finland (paid for through the “Buy a Ford for Finland” fund-raising campaign that was wildly popular with the Australian public, as we will see).

The interesting question one must ask is, why would a country on the far side of the world, with almost no connections with Finland, make such a major commitment to assist a small and almost unknown country in Scandinavia when Australia itself was only just beginning to expand its military for the war against Germany. In considering this question, we will first take a quick look at the state of the Australian armed forces in late 1939, at the same time delving a little into Australian politics and history, primarily World War One and the inter-war years and then take a quick look at the history of Finns in Australia. After that, we’ll look in rather more detail at how Australia reacted to the Winter War. What swayed Australian public and governmental opinion to the extent that the country made the contribution that it did to assist Finland and just what was the full extent of the assistance given by Australia (for it would not be just men to fight)? We’ll consider all of these questions in this and the next couple of Posts.

The state of the Australian armed forces in late 1939

As with Canada and New Zealand, Australia at the end of World War One was in the possession of a well-honed and highly experienced military, blooded in battle in disparate fronts around the world. The AIF had grown through the war, eventually numbering five infantry divisions, two mounted divisions and a mixture of other units. When the war ended, there were 92,000 Australian soldiers in France, 60,000 in England and 17,000 in Egypt, Palestine and Syria. Overall, 421,809 Australians served in the military in WW1 with 331,781 serving overseas. Over 60,000 Australians lost their lives and 137,000 were wounded. As a percentage of forces committed, this was one of the highest casualty rates amongst the British Empire forces. After the War ended, some Australians soldiers in Europe went on to serve in Northern Russia during the Russian Civil War, although officially the Australian government refused to contribute forces to the campaign. HMAS Yarra, Torrens, Swan and Parramatta served in the Black Sea during the same conflict. Elsewhere, in Egypt in early 1919, a number of Australian light horse units were used to quell a nationalist uprising while they were waiting for passage back to Australia.

Despite shortages in shipping, the process of returning the soldiers to Australia was completed rapidly and by September 1919 there were only 10,000 men left in Britain waiting for repatriation. On 1 April 1921, the AIF was officially disbanded. Most of the men of the AIF said good-bye to the army without regret, but there were enough who remained committed to the military to provide a strong cadre of officers, NCOs and men for the re-formed Citizen Force, some of them because they liked the military lifestyle and some out of a conviction that the army they trained or its successor would be called upon to fight again.

Gallipoli and the battles on the Western Front, in which Australian Troops took heavy casualties, made a lasting impression on the Australian psyche, one that has lasted down to the present day. Australian and New Zealand troops landed on the Aegean side of the Gallipoli peninsula near the end of April 1915, and fought there through December 1915, when the troops were evacuated. The Australians lost 8,500 men killed in those few months, New Zealand lost 2,700 – and both the Australians and the New Zealanders placed the blame for these (and the enormous casualties later suffered on the Western Front) firmly on the unthinking, callous and hidebound British Generals. For Australians and New Zealanders, the campaign has been seen as a key moment in a growing sense of national identity. In the context of the Great War, the Gallipoli campaign had little impact but for the men who were there, their families and countless New Zealand and Australian communities, the effects would last for generations, becoming a core part of the ANZAC mythos and permeating the national cultures of both countries.

In the immediate aftermath of World War One, the dead were remembered with a considerable amount of sentimentality: Ray Kernaghan & “Suvla Bay”

In order to advocate for the many thousands of returned servicemen and women many organisations for former servicemen sprang up, te most prominent of which was the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (now the Returned Services Association, or RSA – an Australian and New Zealand icon, particularly in rural areas) which had been established in 1916. Following the war this organisations’ political influence grew along with its numbers, which by 1919 were estimated to be at around 150,000 members. Also in the immediate post-war period, a noticeable number of ex-soldiers entered the political arena in the Australian Parliament, mostly as MPs for the Nationalist Party (and only one as an MP for the Labour Party, which had successfully fought against Conscription in 1916 and 1916). These new MPs (and others in the Nationalist and Country Parties believed that Australian should maintain her links with Britain, and that the Australian military should be maintained at sufficient strength to preserve an effective nucleus for the Armed Forces in the event of another war.

The Australian Labour party, on the other hand, had been reshaped during the war by two historic struggles which overshadowed any other conflicts the Labour movement had experienced. These were the successful campaigns against conscription for overseas service in 1916 and the strikes of 1917. The expulsion from the Labour Party of those members who supported conscription for foreign service had it with a hard core of uncompromising Labour leaders in whose eyes the vital struggle of their period was that between employers and workers – in their eyes the war that had just ended was merely a conflict between two “capitalist” groups . To some of them a khaki tunic was a symbol of “imperialism.” Were not British soldiers in 1920 being employed against the newly-born socialist republic of Russia, against the nationalists of India and, closer still, against Irish patriots struggling for their independence (almost a third of the members of the Labour Party were Irish, or of Irish descent)?

One the left, there was a long-lasting bitterness around the scale of the casualties and the loss of life in an “imperial” war. Eric Bogle’s “Green Fields of France”

Major General Sir Granville de Laune Ryrie KCMG, CB, VD (1 July 1865 – 2 October 1937), Assistant Minister for Defence from 1920 to 1922

In 1920-21, the militia numbered 100,000 compulsorily enlisted men of the 1899, 1900 and 1901 classes, practically untrained, and was equipped with the weapons which the A.I .F. had brought home from Europe and the Middle East – and little else. There was a cadre of 3,150 permanent officers and men, which was about 150 more than there had been in 1914. In the defence debates of 1921, some Labour MP’s advocated going farther than mere reductions and entirely abolishing the army and navy ; others argued that the Australian did not need to begin military training until war began ; “if the war proved anything,” said Mr D. C. McGrath (Labour) “it proved that young Australians many of whom had not previously known one end of a rifle from another were, after training for a month or two, equal to if not superior to any other troops” General Ryrie, the Assistant Minister for Defence at the time, disagreed.

Ryrie worked as a jackaroo (trainee farm manager), and eventually managed his own property. He was also a good heavyweight boxer. He served in the Boer War, where he reached the rank of Major. He was elected to Parliament in 1906 and again in 1911. At the start of WW1, he was promoted to Brigadier-General, and was given command of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade, part of the Anzac Mounted Division, with whom he took part in the famous charge of the Australian Light horse in the battle of Beersheba. After returning to Australia, Ryrie remained a Member of Parliament. In 1920, he was made an Assistant Minister for Defence. In 1927, when he was appointed the Australian High Commissioner in the UK, where he remained until 1932 when he returned to Australia. As Assistant Minister of Defence, Ryrie (who was among the few who believed another war to be possible within a generation) pressed the need for military training and the necessity for maintaining a cadre of skilled officers and men . “Germany”, this veteran soldier said, “is only watching and waiting for the day when she can revenge herself”.

The Ministers who brought forward the modest defence plans of 1920 and 1921 were described by some Labour members as “militarists” and “war mongers”. “We must carefully guard”, said the newly-elected Mr Makin (Labour) “against the spreading in the body politic of the malignant cancer of militarism.” To be fair, many conservatives also advocated reduced defence expenditure at the time. While the Washington Conference negotiating naval strengths was still in session, the Australian Prime Minister, Hughes, had promised Parliament that, if the naval reductions were agreed upon, the defence vote would be substantially reduced . In the following year, nearly half of the ships of the Australian Navy were put out of commission, and it was decided to reduce the permanent staff of the army to 1,600, to maintain the seven militia divisions (five of infantry and two of cavalry) at a strength of about 31,000 men—only 25 per cent of their war strength—and to reduce training to six days in camp and four days at the local centres a year. Seventy-two regular officers out of a meager total of some 300 would be retired.

In the army the sharp edge of this axe was felt most keenly by two relatively small groups. The first was the small Officer corps – careful selection, thorough technical training and moulding of character by picked instructors, followed immediately by active service, had produced an officer corps which, though small, was of fine quality. Before and during the war of 1914-18 each young officer saw a brilliant career ahead of him if he survived. The reductions of 1922 dashed these hopes. It was unlikely that there would be any promotion for most of them for ten years at least. Until then they would wear the badges of rank and use the titles attained on active service, but would be paid as subalterns and fill appointments far junior to those that many of them had held for the last two or three years in France or Palestine .

Even more rigorous had been the reduction in rank of the warrant officers, some of whom had become Lieutenant-Colonels and commanded battalions in the war . They were debarred from appointment to the officer corps — the Staff Corps as it was now named — entry to which was reserved to pre-war regular officers and graduates of Duntroon, and became, at the best, quartermasters, wearing without the corresponding pay and without hope of promotion the rank that they had won in the war. Australia’s defence now became tied to the proposed construction of a naval base the naval base at Singapore – not without opposition from the Labour Party As a consequence of the 1923 conference, the Bruce-Page Government decided to buy two 10,000-ton cruisers and two submarines at a cost of some £5,000,000, whereas, over a period of five years, only £1,000,000 would be spent on additional artillery, ammunition and antigas equipment for the army. In these five years expenditure on the navy aggregated £20,000,000; on the army, including the munitions factories, only £10,000,000; on the air force £2,400,000. The strength of the permanent military forces remained at approximately 1,750, whereas that of the navy rose, by 1928, to more than 5,000 personnel.

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967)

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC (15 April 1883 – 25 August 1967) was Prime Minister of Australia from February 1923 to 1929. Born in Melbourne, his father was a prominent businessman. He was educated at Glamorgan (now part of Geelong Grammar School), Melbourne Grammar School, and then at Cambridge University. After graduation he studied law in London and was called to the bar in 1907. He practised law in London, and also managed the London office of his father’s importing business. When World War I broke out he joined the British Army, and was commissioned into the Worcestershire Regiment, seconded to the Royal Fusiliers. In 1917 he was severely wounded in France, winning the Military Cross and the Croix de Guerre. He was invalided home to Melbourne, and became involved in recruiting campaigns for the Army. His public speaking attracted the attention of the Nationalist Party, and in 1918 he was elected to the House of Representatives as MP for Flinders, near Melbourne. His background in business led to his being appointed Treasurer (Finance Minister) in 1921. The Nationalist Party lost its majority at the 1922 election, and could only stay in office with the support of the Country Party. However, the Country Party let it be known it would not serve under incumbent Prime Minister Billy Hughes. This gave the more conservative members of the Nationalist Party an excuse to force Hughes (whom they had only tolerated to keep the Australian Labor Party out of power) to resign. Bruce was chosen as Hughes’s successor, after which a conservative coalition government was formed.

With his aristocratic manners and dress – he drove a Rolls Royce and wore white spats – he was also the first genuinely “Tory” Prime Minister of Australia. Bruce formed an effective partnership with Page, exploiting public fears of Communism and militant trade unions to dominate Australian politics through the 1920s. Despite predictions that Australians would not accept such an aloof leader as Bruce, he won a smashing victory over a demoralised Labour Party at the 1925 election. Throughout his term of office, he pursued a policy of support for the British Empire, the League of Nations, and the White Australia Policy. His government was reelected, though with a significantly reduced majority, in 1928. Strikes of sugar mill workers in 1927, waterside workers in 1928, then of transport workers, timber industry workers and coal miners erupted in riots and lockouts in New South Wales in 1929. Bruce responded with a Maritime Industries Bill that was designed to do away with the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration and return arbitration powers to the States. On 10 September 1929, Hughes and five other Nationalist members joined Labor in voting against the Bill. The Bill was lost by 34 votes to 35 when the Speaker abstained, bringing down the Bruce–Page government and forcing the1929 election. Labor, now led by James Scullin, won a landslide victory, scoring an 18-seat swing—at the time, the second-worst defeat of a sitting government in Australian history. Bruce was defeated by Labor’s candidate Jack Holloway in his electorate of Flinders, making him the first sitting prime minister to lose his seat.

After his 1929 defeat, Bruce went to England for personal and business reasons, contesting the 1931 election from that country as a member of the United Australia Party (a merger of Bruce’s Nationalists and Labor dissidents). He won his seat back and was named a Minister without portfolio in the government of Joseph Lyons. Lyons immediately dispatched Bruce back to England to represent the government there, following which he led the Australian delegation to the 1932 Ottawa Imperial Conference. When Bruce sailed for the UK and then Ottawa in June 1932, his career in politics was over. Well before his return, Lyons offered him the high commissionership in London and when Bruce endeavoured to defer his decision, Lyons forced the issue in September 1933. At Ottawa Bruce consolidated his reputation as a tough negotiator. From there he went to London to renegotiate Australia’s debt. Blocked by a government embargo on the raising of new capital, Bruce used his old City contacts to break through. As Australian High Commissioner in London from 1933-45, Bruce secured a solid reputation as an international statesman, travelling between London and Geneva while crisis succeeded crisis and the League of Nations floundered. When Turkey sought revision of the Straits Convention in 1936 Bruce was accepted unanimously as president of the Montreux conference and his chairing of it was widely acclaimed.

Meeting as an equal with British ministers in Geneva, it became easier in London to get access to senior ministers and to confidential information which enabled him to be accepted as an adviser to the British government in his own right, while also acting as the main adviser to the Australian government. His technique was to send a situation-appraisal to his Prime Minister with prior warning of the decision he might need to take, so that in most instances the decision when made was as Bruce advised. During the Abyssinian crisis Bruce was a reluctant supporter of sanctions and among the first to advise reconciliation with Italy after partial sanctions had failed to save Abyssinia. The key to peace in Europe he thought was to detach Italy from Germany. He urged the British to recognize this and to formulate clearly their intentions regarding Germany’s claims. France, he repeatedly warned, would drag England into a European war: France would neither concede anything to Germany nor take effective action to block her, would not fight for Czechoslovakia, and could not assist Poland. An “unfulfillable guarantee” to Poland was of utmost danger. In the last days before the war Bruce desperately tried to avert that disaster.

His concern throughout was for the repercussions on Australia of Britain’s situation in Europe and her lack of policy on China: Bruce recognized that the real danger to Australia lay in a Pacific war coinciding with a European war. As early as 1933 he was warning Australian ministers that the Royal Navy might not be available when needed: nevertheless he continued seeking assurances that it would. In 1938 he began negotiations for large-scale aircraft production in the Dominions, seeking guaranteed orders and technical assistance from England to make an Australian plant viable. In December 1938 on his way to Australia and in May 1939 on his way back, Bruce had seen the American president. The conversations dealt with the likelihood of American support if Japan moved south, but the president regarded a public commitment as premature. When war started Bruce and Prime Minister (Sir Robert) Menzies were in complete agreement that Australia should not commit its forces to a European war while Japan’s intentions were unclear. Foreseeing the rapidity with which Poland would be over run, Bruce had tried to mobilize support for a clear definition of peace aims, hoping thereby to avert the destruction of Europe. Meeting with little success, he had put his hopes on Churchill, only to find he had no aim but to smash Germany. Throughout the “phoney war” Bruce pursued this issue beyond the tolerance of erstwhile admirers in high circles.

Bruce regarding the New Zealand High Commissioner’s support for an ANZAC volunteer unit to fight in Finland alongside the Finns as an unwelcome distraction and was not a supporter of the move – however, he did follow instructions from Menzies to assist New Zealand despite his own misgivings as to the policy being followed. He advocated strongly against any further Australian support being offered, but was over-ruled. The success of the Finns, and the considerable publicity accorded the successes of the Australian Volunteers in Finland led to a further reduction in Menzies’ reliance on Bruce. Nevertheless, Bruce continued on as High Commissioner, loyally serving every wartime Australian government. He joined the War Cabinet in 1942 but had little influence, to his chagrin he found he was invited only on selected occasions and in August 1945 his retirement was announced. In 1947 he became the first Australian created a hereditary peer when he was made Viscount Bruce of Melbourne. He was also the first Australian to take a seat in the House of Lords. Bruce divided the rest of his life between London and Melbourne. He represented Australia on various UN bodies, was the chairman of the World Food Council for five years and was appointed as the first Chancellor of the Australian National University, a position he held from 1951 until 1961. He died in London on 25 August 1967, aged 84.

During this period the strength of the militia varied between 37,000 and 46,000 and it was a nucleus which did not possess the equipment nor receive the training “essential to the effective performance of its functions”. It lacked necessary arms, including tanks and anti-aircraft guns and there was not a large enough rank and file with which to train leaders to replace those hitherto drawn from the old A .I .F.—a source of supply which had dried up . In the regular officer corps of 242 officers there was a “disparity of opportunity and stagnation in promotion, with retention in subordinate positions, cannot lead to the maintenance of the active, virile and efficient staff that the service demands”. The only mobile regular unit for example was a section of field artillery consisting of fifty-nine men with two guns. In the long debates on the naval proposals of the Bruce-Page Government, the defence policy of the Labour Opposition was defined . Whereas the Government’s policy was to emphasise naval expenditure, Labour ‘s proposal was to rely chiefly on air power and the extension of the munitions industry . However, the Labour party was to be in office for just over two years in the period between the wars. Consequently Australia’s defence policy closely followed the principles set down in 1923 – these emphasised ultimate reliance on the British Navy to which Australia would contribute an independent squadron as strong as she considered she could afford, and a reliance on the base at Singapore, from which the British fleet would operate in defence of British Far Eastern and Pacific interests . At the same time a nucleus militia, air force, and munitions industry would be maintained.

The army did not share in the comparatively small increases that were made in the defence vote each year from 1924 to 1928 . The effectiveness of the militia continued to decline while the tiny permanent force together with militia officers and men carried on staunchly despite discouragement and a lack of any material reward. However, the system whereby each young lieutenant spent a year with the British Army in the United Kingdom or India, and a number of more-senior officers were always overseas on exchange duty or attending courses at British schools helped to keep the officer corps from stagnation. Gains in equipment were microscopic: in 1926 the army obtained its first motor vehicles—five 30-cwt lorries, one for each military district except the Sixth (Tasmania), and eight tractors for the artillery; in 1927 four light tanks arrived.

Nor could the army comfort itself with the reflection that, when the need arose, it could commandeer even enough horses, because, the breeding of working horses had so declined that Australia was not only losing her export trade in army horses but it was doubtful whether there were enough suitable animals in the continent to mobilise the seven divisions . To the militia officers these circumstances were equally discouraging, and the fact that they were willing to devote their spare time to so exacting a hobby—and a keen officer had to give all his leisure to it – was evidence of uncommon enthusiasm for soldiering and, in most instances, an impelling desire to perform a public service.

By the late 1920s, the numbers of horses in Australia had seriously declined, such that not only was Australia losing her export trade in Army Horses (the famous Walers), it was highly doubtful that there were enough horses available to meet all the transport requirements of the mobilized seven divisions of the Australian Army. This contrast with the situation in WW1, where Australia exported hundreds of thousands of horses for use by the military in the Middle East, Africa and Europe. More horses than men died in WW1.

Australian Militia in the Inter-war years

Peace-time military service conferred little prestige – indeed, an Australian who made the militia a hobby was likely to be regarded by his acquaintances as a peculiar fellow with an eccentric taste for uniforms and the exercise of petty authority. Soldiers and soldiering were in particularly bad odour in the late ‘twenties . From 1927 onwards for four or five years, a sudden revival of interest in the war that had ended ten years before produced a series of angry war novels and memoirs of which Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front”, Robert Graves’ “Good-bye to All That” and Arnold Zweig’s “The Case of Sergeant Grischa” were among the most popular. Whether this criticism was right or wrong, these books and the plays and moving pictures that accompanied them undoubtedly did much to mould the attitude of the people generally and particularly of the intelligentsia to war and soldiers, and produced rather widely a conviction that wars are always ineffectual, are brought about by military leaders and by the large engineering industries which profit by making weapons, and that if soldiers and armaments could be abolished wars would cease. It was, however, not so much a desire for disarmament, and for the peace which was widely believed to be the sequel to disarmament, but another factor that was to produce substantial and sudden reductions in the armies and navies of the world. In October 1929 share prices in New York began to collapse; soon the entire world was suffering an acute economic depression.

The Labour Party had taken office in Australia in October 1929 for the first time since the conscription crisis of 1917, and the day after the first sudden drop on the New York Stock Exchange. Before the full effects of the distant catastrophe were apparent, the new Ministers who, harking back to an old controversy, had promised the electors that if the Labour party was returned it would abolish compulsory training, ordered (on 1st November 1929) that conscription be suspended, and cancelled all military camps arranged for the current year . At the same time the new Prime Minister, Mr Scullin, instructed the Defence Committee to submit an alternative plan for an equally adequate defence. There would, he said, be no discharges of permanent staff . Accordingly the Defence Council submitted a plan, which was eventually adopted, to maintain a voluntary militia of 35,000 with 7,000 senior cadets. The reaction of Mr Roland Green (Country Party) who had lost a leg serving in the infantry in WW1 was an indication of the feelings that were aroused. Green made a bitter speech in the House of Representatives recalling that Scullin and other Labour leaders, including Messrs Makin, Holloway and Blackburn, had attended a Labour Party conference in Perth in June 1918 when a resolution was passed that if the Imperial authorities did not at once open negotiations for peace, the Australian divisions should be brought back to Australia, and calling on the organized workers of every country to take similar action . “As a result of that attitude”, said Green, “Labour was out of office in the Commonwealth for thirteen years, largely because of the votes of the soldiers and their friends. During all that time the party nursed its hatred of the soldiers, and now it is seeking revenge”

Gallipoli became a core part of the ANZAC mythos, permeating the national cultures of both countries. Part of that myth was the pervasive image of the British General’s as butchers – an image that would result in Australia (and New Zealand to a lesser extent) ensuring it’s Divisions could if necessary refuse to participate in British operations if an action was seen as against Australia’s interests – something that would occur a number of times in WW2: This image is perhaps best portrayed in popular Australasian culture in Eric Bogle’s “The Band Played Waltzing Matilda”

James Scullin, (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953), Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia.

James Scullin, (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953), Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Scullin joined the Labor Party in 1903 and became an organiser for the Australian Workers’ Union. In 1913, he became editor of a Labor newspaper in Ballarat, the Evening Echo. Scullin stood for the House of Representatives in 1906 but lost. In 1910 he was elected to the House but was then defeated in 1913 and went back to editing the Evening Echo. He established a reputation as one of Labor’s leading public speakers and experts on finance, and was a strong opponent of conscription. After World War I he came close to outright pacifism. In 1922 he won a by-election for the safe Labor seat of Yarra in inner Melbourne, and in 1928 he was elected Labor leader. He was Prime Minister of Australia from 1929 to December 1931, when his government was defeated in a landslide swing to the Opposition. He remained as leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party until 1934, after which he resigned but remained in Parliament as a backbencher until 1949.

The abolition of compulsory military training resulted in the burden of carrying out the new government’s policies falling upon the same small and over-tried team of officers, both professional and amateur, who had tenaciously been maintaining the spirit and efficiency of the citizen army through nine lean years and now had even leaner ones to look forward to. They “rose to the occasion” and in the first four months of 1930 their recruiting efforts produced a new militia of 24,000, with an additional 5,300 in the volunteer senior cadets—a relic of the big, well-organised cadet force in which all boys of 14 to 17 had formerly been given elementary military training. The numbers increased gradually, between 1931 and 1936 the number of militiamen fluctuated between 26,000 and 29,000. This strength, however, was about 2,000 fewer than that of 1901 ; the permanent force too stood at about the same figure as it had twenty-nine years before. In 1901, when the population of Australia was 3,824,000, the permanent forces had been 1,544, the partly-paid militia and unpaid volunteers 27,400. In June 1930, when the population was 6,500,000, the permanent forces totaled 1,669 and the militia 25,785.

The abolition of compulsory training had been based purely on political doctrine but within a few months the depression resulted in still more severe reductions in the three Services. Defence expenditure was reduced from £6,536,000 in 1928-29 to £3,859,000 in 1930-31 and hundreds of officers and men were discharged from all three services. Further discharges were avoided only by requiring officers and men to take up to eight weeks’ annual leave without pay. A number of regular officers resigned, others transferred to the British or Indian Armies.

However, before the world had emerged from the depression, signs of war appeared in Asia and Europe. In 1931, Japan had begun to occupy Manchuria, in 1933, Hitler’s National-Socialist movement gained power and Germany withdrew from the Disarmament Conference and the League of Nations. Before this critical year was over, the need for repairing the armed services was being canvassed by politicians and publicists in Australia . Brig-General McNicoll, one of a group of soldiers, professional and citizen, who had been elected to the Federal Parliament in 1931 when the Labour party was defeated, declared that “a wave of enthusiasm …. has passed over Australia about the need for effective defence”. This was perhaps an exaggeration, but nevertheless, there was undoubtedly evidence of some alarm and of an increasing discussion of foreign affairs and their significance to Australia. The response of the United Australia Party, successor to the Nationalist party and now the Government, was cautious. The Government considered that its first responsibility was to bring about economic recovery. Between 1933 and 1935 the defence vote increased only gradually.

The Government adopted its policy ready-made and with little amendment, from the Committee of Imperial Defence. A weakness of this body was that it contained no permanent representatives of the Dominions. Such representatives might be summoned to advise on business that closely affected their governments, and would attend during Imperial conferences, exchange of senior officers in all Services, and the attendance of Dominions’ officers at the English staff colleges and the Imperial Defence College somewhat strengthened liaison and encouraged discussion of higher policy. But, if Australian and New Zealand officers at those colleges frequently expressed disagreement with British military policy towards the problem of Japan, for example, that fact was not likely to affect the plans of the Committee of Imperial Defence, whose permanent members, secretary, four assistant secretaries (one from each Service and one from India) were servants of the United Kingdom Government . The committee carried out continuous studies of Imperial war problems but without an influential contribution from the Dominions. It shaped a military policy which carried great weight with Dominion ministers ; yet in the eyes of Dominion soldiers the committee could justly be regarded as a somewhat parochial group, since it was possible that none of its members had ever been in a Dominion or in the Far East .

Within Australia an outcome of dependence on advice from London and the consequent failure to develop a home-grown defence plan was that successive ministers failed also to work out a policy which, while integrated with the plans of the British Commonwealth as a whole, reconciled the differing viewpoints of the army and the navy. Always the ministers’ aim seemed to be to make a compromise division of the allotted defence budget (invariably too small to be effective) among three competing services. Both Government and Labour defence theories were strongly criticised. The Government policy was attacked by some Government supporters as well as by the Labour Opposition on the ground that it disregarded that the British Navy did not, and could not spare a sufficient force to command Eastern seas, that Britain lacked the military and air power even to defend her own bases in the East, and therefore that Australia should take what measures she could to defend herself. Labour’s policy was denounced because it left out of account that Australia’s fate could and probably would be decided in distant seas or on distant battlefields. Gradually those members of the Labour party who had begun to inform themselves upon defence problems discovered that leaders of Australian military thought were able to go part of the way with them .

In their ten-years-old argument against Naval doctrines and particularly against the Singapore thesis the Australian Army leaders had adopted a position not far removed from that which the Labour party was reaching. Thus, when Admiral Richmond, the senior British naval theorist of his day, attacked, in the British Army Quarterly, a theory of Australian defence that resembled the Labour party’s in some respects, his argument was countered (in the same journal) by Colonel Lavarack, then Commandant of the Royal Military College, Duntroon. And when, in 1936, a lecture which had been given to a small group of officers sixteen months before by Colonel Wynter, the Director of Military Training, came into the hand of Mr Curtin, leader of the Parliamentary Labour Party, he read it, without betraying its authorship, as a speech in the House, presumably as an expression of the policy of his party. This incident and another similar occurrence in the same year added greatly to the resentment felt by the regular officer corps towards the right-wing political leaders. The copy of Wynter’s lecture, which contained substantially the same argument as he had published in an English journal ten years before, had been handed to Curtin by a member of the Government party who, like others of that party, was critical of the Government’s defence policy . Four months later Wynter was transferred to a very junior post. One month after Wynter ‘s demotion Lieut-Colonel Beavis, a highly-qualified equipment officer with long training and experience in England, who had been chosen to advise on and coordinate plans for manufacturing arms and equipment in Australia was similarly transferred to a relatively junior post after differences of opinion with a senior departmental official.

John Joseph Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945), 14th Prime Minister of Australia

John Joseph Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945), Australian politician, served as the 14th Prime Minister of Australia. Labor under Curtin formed a minority government in 1941 after two independent MPs crossed the floor in the House of Representatives, bringing down the Coalition government of Robert Menzies, resulting in the September 1940 election. Curtin led federal Labor to its greatest win with two thirds of seats in the lower house and over 58 percent of the two-party preferred vote, and 55 percent of the primary vote and a majority of seats in the Senate at the 1943 election. Curtin led Australia when the Australian mainland came under direct military threat during the Japanese advance in World War II. He is widely regarded as one of the country’s greatest Prime Ministers. General Douglas MacArthur said that Curtin was “one of the greatest of the wartime statesmen”. Curtin died in 1945. It was Curtin’s decision that would see an Australian Division sent to fight alongside the Maavoimat in 1944 and 1945. It was an unpopular decision with many on the left wing of the Labour Party. Ben Chifley, who succeeded Curtin as Prime Minister and who led the Labour Party to victory in 1946, would later say about fighting alongside Finland “It was a decision that was not supported by the Left of the Party, but it was one that resonated with the people of Australian, who still remembered “plucky little Finland” and the part that Australians played in the Winter War – and it certainly helped the Labour Party in the elections of 1946 with the returned soldiers vote.”

From 1935 onwards, defence was becoming a topic of major interest in the newspapers and reviews . More books and pamphlets on the subject were published between 1935 and 1939 than during the previous thirty-four years. Expenditure on defence was slightly increased year by year, and there was an awareness in political circles that there was a growing public opinion in favour of more rapid progress. For the army the three-year plan (for the years 1934-35 to 1936-37) included the purchase of motor vehicles on a limited scale, increased stocks of ammunition, and “an installment of modern technical equipment”. The Army could not mobilise even a brigade without commandeering civil vehicles, and now had to base its plans on the assumption that it would be engaged, if war came, against armies (such as the German) whose weapons belonged to a new epoch.

After the Imperial Conference of 1937, Australian Army leaders now pressed for accelerated expenditure on the equipment of the field army, even if it meant rearming the coast defences more slowly, arguing that coast defences might be taken in the rear if the field army was not converted into an effective force. As the threat of war became more apparent so the Labour party, under Curtin’s leadership, based its defence policy, at the technical level, more and more definitely on the doctrines of those military and naval critics who contended that Australia first and foremost must prepare defence against invasion during a critical period when she might be isolated from Britain and the United States. The Government leaders however, stood firmly by the decisions of 1923—a “fair contribution” to an “essentially naval” scheme of Imperial defence. Defence expenditure continued to rise year by year, in 1935-36 it reached £7,583,822, which was the largest in any year since WW1. In the next year, the figure rose to £8,829,655. In 1938 (when taxation was increased for the first time since 1932) defence spending rose again.

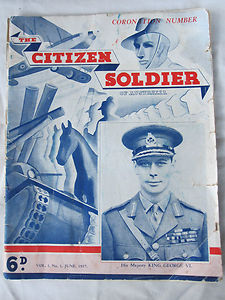

Australian 1930’s Militia Magazine – from 1937

In 1935, for the first time since the depression, the Army’s budget was raised to approximately the sum that it had received in the mid 1920’s. A relatively young officer, Colonel Lavarack, was promoted over the heads of a number of his colleagues and made Chief of the General Staff . The army whose rebuilding he had to control consisted of 1,800 “permanent” officers and other ranks (compared with 3,000 in 1914) and 27,000 militiamen (compared with 42,000 in 1914). Its equipment had changed little since the A.I.F. had brought it home from France and Palestine ; and it was equipment only of the seven divisions, not for the many supporting units that are needed for an army based on seven divisions—such units had been provided in the war of 1914-18 by the British Army . It lacked mortars, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns; it lacked tanks, armoured cars, and a variety of engineer and signal gear; it had inadequate reserves of ammunition. In recommending how the moderately-increased army vote be spent Lavarack’s policy did not differ materially from that laid down fifteen years before by the Senior Officers’ Conference of 1920; broadly it was for training of commanders and staff first, equipment next, and, lastly, the training (or semi-training, for that is all it could be) of more militiamen. Full mobilization would bring into the field the five infantry and two cavalry divisions, 200,000 men in all not allowing for reinforcements . To produce such a force would demand an exacting national effort; on the purely military level it would be necessary, for example, for each brigade of three nucleus battalions not only to bring itself to full strength but to produce a fourth battalion. (The army at that time was still planning on a basis of four battalion brigades). The leaders were thus faced with the problem of making plans for a full mobilisation which would entail expanding each so-called brigade of perhaps 900 partly-trained and poorly-equipped militia, without transport, into a full brigade of some 3,600 fully equipped and mobile infantrymen.

Plans for full mobilisation were based on the assumption that the enemy (Japan) would attack at a time when Australia was isolated from British or American naval aid and would seek a quick decision . The enemy, using carrier-borne aircraft, would, it was assumed, first attempt to destroy the defending air force and to impose a blockade . He would then occupy an advanced naval and air base somewhere outside the relatively well-defended Newcastle-Sydney-Port Kembla area. When his main force was ready he could move overland from this advanced base, whence his force would receive the protection of land-based aircraft, or he could make a new landing farther south . The Australian mobilisation plans provided for the concentration of the greater part of the army in the vital Newcastle-Port Kembla area; the army could not be strong everywhere. It was seen that the accomplishment of even such a modest plan of military defence would take years to achieve despite the larger funds that the Government was then allotting . The sum of £1,811,000 was spent on the army in 1935-36, £2,232,000 in 1936-37, £2,182,000 in 1937-38 ; but one battery of 9.2-inch coast defence guns with its essential equipment cost £300,000, a battery of anti-aircraft guns with its gear and ammunition cost £150,000 . In fact, until the crises of 1938, the army received only enough to repair some of the deficiencies it had suffered under since 1918. The army leaders, in whom the years of parsimony had produced a distrust of politicians, were resolved to spend such funds as they received on something that the politician could not take away from them if the crisis seemed to have passed and the army’s income could be cut again . Thus there was this additional reason for giving priority to guns and concrete rather than men and training: that if the vote was again reduced, the guns and concrete would remain.

In the first two months of 1938, events in Europe and China began to move too rapidly to permit leisurely rearmament. Evidence of the alarm that was felt by the Australian Government was provided a month later when the Government announced that it proposed to spend £43,000,000 on the fighting Services and munitions over the next three years. This was more than twice what had been spent in the previous three years. The army would receive £11,500,000, the air force £ 12,500,000 and the navy £15,000,000. Since 1920 the navy had year by year received more money than the army; now, for the first time, the air force too was promised a larger appropriation than the army’s. Compared with the sum it had been receiving before, the army’s new income, though the least of the three Services’, was astronomical. In December 1938, after the Munich crisis the newly appointed Minister for Defence announced that the total of £43,000,000 for defence would be increased by an additional £19,504,000 to be spent during the three years which would end in 1941. As a result of a recruiting campaign directed by Major-General Sir Thomas Blarney, the militia was increased in numbers from 35,000 in September to 43,000 at the end of 1938 and 70,000, which was the objective, in March 1939 – 22,000 more than the conscripted militia of 1929.

Men in Melbourne collecting recruitment papers

The promise of funds, the successful recruiting campaign and later, the taking of a national register (which was vehemently resisted by trade union organisations as being a step towards military and industrial conscription) sufficed to give citizens the impression that something was being done . It was too late, however, to achieve before war broke out what was far more important than these parades and promises, namely adequate equipment. Machines and weapons which the Australian Army, like the air force, had ordered four years before had not been delivered from British factories, which were fully employed in a last-minute effort to equip the British Armed Forces.

What had been achieved by twenty years of militia training? There were in 1914 and again in 1939 three kinds of armies. The long service volunteer regular armies of Great Britain and the United States were able to attain a high degree of unit efficiency, though this was offset by the higher commanders’ lack of experience in handling large formations. Next in order of efficiency came the large conscript armies of which, in Europe, the German had for generations been the model. With an expert general staff and, in each formation, a strong cadre of professional officers and NCOs, and a rank and file trained for periods ranging up to two or three years, these immense armies were able to move and fight at short notice. In a third category fell the militia armies maintained by nations influenced by a desire for economy or a belief, real or imaginary, in their relative security. Some of these nations—the Swiss for example—managed to create relatively effective militias by insisting on a period of initial training long enough to bring the recruits to a moderate standard of individual efficiency . But in the Australian militia (the British Territorial Army, New Zealand Territorial Army, the Canadian Militia and the United States National Guard fell into much the same category) the recruit lacked this basic training and had to acquire his skill as best he could during evening or one-day parades and brief periods in camp. In Australia, in spite of the brevity of the annual training given to the enthusiastic volunteer militiamen, they were made to undertake complicated and arduous exercises. It was decided that to spend one camp after another vainly trying to reach a good standard of individual training was likely to destroy the keenness of young recruits and was of small value to the leaders.

However, so far as the aim of the Australian system had been to produce an army ready to advance against an enemy or even to offer effective opposition to an invader at short notice it had failed. At no time, either under the compulsory or the voluntary system, had the militia been sufficiently well trained to meet on equal terms an army of the European type based on two or three years of conscript service, and experience was to prove that perhaps six months of additional training with full equipment would be needed to reach such a standard . However, it would be wrong to conclude that the system had not achieved valuable results, and that the devoted effort of the officers and men who had given years of spare-time service had been wasted. The militia had not and could not make efficient private soldiers, but it did produce both a nucleus of officers who were capable of successfully commanding platoons, companies and battalions in action, and a body of useful NCOs. These men were fortunate to have been trained by highly-qualified professional and citizen soldiers who had seen hard regimental service in the war of 1914-18 and were able to hand down to them the traditions of the outstanding force in which they had been schooled (to that extent the militia owed its effectiveness more to the old A .I.F. than to its own system).

And it should not be imagined that, because units were trained for only a week or two a year, the militia officers received no more experience than that. They generally gave much additional time to week-end and evening classes, to tactical exercises without troops and to reading, and the keenest among them attained a thorough knowledge of military fundamentals. A large proportion (but not always large enough, particularly in some city infantry units) were men of good education, and leaders in their professions. Genuine enthusiasm for soldiering was demanded of them, and there were few who did not suffer disadvantages in their civilian work because of their military service. Indeed, an important factor in the small attendances of other ranks at camps was the frequent inability of men to obtain leave from unpatriotic employers (and they were in a majority) except on prejudicial terms such as curtailment of annual vacations and delay in promotion and an efficient officer had to give to military work much time that he could otherwise have spent profitably on his civilian business.

The larger question of what had the Australian Government done between the wars to enable the military to carry out its responsibilities can be summarized briefly? In the inter-war period Australia had become a fully-independent nation, an enhancement of status in which she took some pride. Her population had increased by nearly two million people and her industrial equipment had been vastly elaborated. There had been a corresponding increase in her responsibilities as a member of the British Commonwealth; and the military leaders of the UK had declared that in a major war the immediate help of trained, equipped forces from the Dominions would be needed. Yet in 1939 Australia possessed an army little different in essentials from that of 1914. It was fundamentally a defensive force intended if war broke out to go to its stations or man the coastal forts and await the arrival of an invader. History had proved and was to prove again the futility of such a military policy. The measures that had been taken in the few years of “re-armament” were insignificant in the face of the threat offered by two aggressive Powers, one of which desired to master Europe, the other East Asia.

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland

Copyright secured by Digiprove © 2013 Alternative Finland