While the French Government discussed aid from France to Finland, tangible results were slow to eventuate. The first substantial aid to arrive from France was a shipment of thirty Morane-Saulnier fighters. France had promised 50 of these first-rate fighter aircraft but initially only 30 were sent (the remaining 20 were in fact never sent). They were shipped to Sweden and assembled by French mechanics at AB Aerotransport’s facilities at Bulltofta airfield at Malmö, Sweden. The aircraft were flown from Sweden to Finland between 4 and 29 Feb, 1940 where they entered service immediately.

Morane-Saulnier MS406 Fighters for Finland

With a rapidly deteriorating international situation, facing ever increasing pressure from the Soviet Union, and shocked by the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 (and aware of the secret clauses regarding Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania), the Finnish military procurement program had moved into high gear, with Mannerheim in particular using all his considerable personal leverage with the French, Italians, British and Americans in an attempt to prepare Finland for the european-wide war he was sure was coming. However, the sad fact of life was that all of these countries were busy preparing for war themselves and Mannerheim’s personal relationships held no sway. Still, while Mannerheim could at least console himself with the thought that Finland was considerably more prepared than it might have been, the situation was still perilous and Finland continued to make every possible effort to secure additional military equipment.

Negotiations with France however would prove unavailing. French armaments production was well behind schedule and in any case, Finland had no real expectation that the French would be of much assistance – Finland’s hopes were rather more heavily weighted towards the Americans and their massive industrial capacity. However, when Germany attacked Poland on September 1st, 1939, a further Finnish attempt to place an urgent order for forty Morane-Saulnier MS-406’s was again declined by the French Governmen. Finland was advised that with the declarations of war by France and Britain, all aircraft manufacturing output was going to equip the French Air Force and none were available for sale.

French Morane-Saulnier MS 406 aircraft on patrol

However, soon after the actual outbreak of the Winter War on 31 November 1939, the French Government changed its mind and agreed to donate 50 MS 406s to Finland. An initial shipment of 30 aircraft arrived in Sweden in early January 1940, where (as mentioned above) they were assembled by French mechanics at AB Aerotransport’s facilities at Bulltofta airfield at Malmö, Sweden. French test pilots Captains Etienne and Henri Sabary flew each plane before they were handed over to the Finns. Finnish Ilmavoimat Ferry pilots (mostly women) flew the planes from Sweden to Finland with the aircraft already painted with Finnish national markings although the planes still had a French paint scheme.

The picture shows an incident along a Soviet rear-area railway line. Ilmavoimat Morane-Saulnier pilots destroyed over 40 railway engines in the Winter War. This impaired transport of military materiel to the Finnish front

Early trials in Finland identified that at high altitude the guns had a tendency to freeze up and heaters were quickly added to the guns to allow high altitude use. The end result was an effective fighter capable of taking on the best of the Soviet fighters. The Finnish nicknames were Murjaani (blackmoor), a twist on its name, and Mätimaha (roe-belly) and Riippuvatsa (hanging belly) for its bulged ventral fuselage. The thirty MS 406’s would enter service in March 1940 and would fight through the Winter War.

The 30 MS 406 fighters that were delivered in early 1940 were allocated to LeLv 28, commanded by Major Jusu. These aircraft received the Finnish designations MS-301 to MS-330. They were used heavily in combat during the Winter War against the USSR and shot down 134 Soviet aircraft for 15 aircraft lost. The top Morane ace in all theatres was W/O Urho Lehtovaara.

The original of this print is a watercolour painting by the artist Sture Gripenberg with a printing limited to 400 copies. Master Sergeants Erkki Alkio and Oskari Jussila, together with the artist Sture Gripenberg have personally signed each numbered print (link to the artists website is http://personal.eunet.fi/pp/gdes/gallery_eng.htm)

Urho Sakari Lehtovaara – the Ilmavoimat’s top-scoring Morane-Saulnier Pilot

Urho Sakari Lehtovaara was born in Pyhäjärvi, northern Finland on 17 October 1917. He lived there until the family moved to Salo in 1934. There he became interested in the activities of the local aero club. The club was building a glider, and soon Urho was the most enthusiastic member of the club. Lehtovaara volunteered for military service in the Air Force in 1937. He liked flying so much that he decided to earn his living at it, remaining in service as an enlisted NCO (Lance Corporal) in LeLv 26, at first flying the old Bristol Bulldog fighters and then the newer Avia B-534’s. With the rapid expansion of the Ilmavoimat in the last half of the 1930’s, he would find himself spending a considerable amount of his time flying with trainee pilots as the Ilmavoimat concentrated on building a large reserve force.

Physically Lehtovaara was a short man, which is why he gained his nickname of “Pikku-Jätti” (Little Giant) or later plain “Jätti” (“Giant”) when he had proven his real size. His character was introverted, he did not talk much, and usually he was calm and pensive, but if sufficiently provoked he could suddenly lose his temper. Obviously he disliked the attention when photographed as he always looks sullen in the photos. When he was decorated with the Mannerheim Cross on the 9th of July 1944 he was characterized: “as fighter pilot Sergeant Major Lehtovaara has displayed exemplary courage combined with great calmness and judgment”.

When the Winter War broke out in late 1939, Lehtovaara’s squadron still was equipped with the older Avia B-534’s. When the Morane-Saulnier MS-406 fighters donated by the French government became operational in late February 1940 a new squadron, LeLv 28, was created. Sgt. Lehtovaara was one of the pilots transferred to the new unit. The flight in which he served was based on Lake Pyhäjärvi near Turku. Unfortunately the Moranes as delivered were very inefficient interceptors due to a total lack of radio equipment and the weak armament of only three 7.5 mm MG’s. (Very few planes had the French-manufactured 20mm Hispano cannon, which was even less reliable than the MAC machine guns). Moreover, the MS-406 was unstable with a tendancy to oscillate vertically after a turn, making accurate longer-range shooting impossible. The Ilmavoimat moved as fast as possible to rectify these problems – the first measure taken being the installation of radios as soon as these could be made available. The second was the installation of Finnish-manufactured HS404 20mm cannon, which were far more reliable than the French-manufactured guns. However, these retrofits would take place over time and in early March 1940 had not yet been started, meaning the Morane’s could not be vectored onto enemy aircraft by Fighter Control.

Urho Sakari Lehtovaara in front of his Morane Saulnier 406, MS-327, as it is being reloaded for another mission. Note the MAC gun ammo drum on the wing and the wing guns tilted for reloading. The MS-406 demanded twice more labour for service than any other FAF fighter type.

On 2nd March 1940 Lehtovaara’s flight commander received a report of a lone enemy bomber over the town of Salo. He sent out Lehtovaara with MS-326, an eager volunteer as he knew the “lie of the land”. The Morane reached Salo in less than ten minutes but of course the enemy was not there any more. Lehtovaara decided to fly around before returning, and after a minute he saw a two-engine plane. He flew closer and saw that it was an SB-2 with red stars. Lehtovaara decided to play safe, considering that he had a chance of making his first kill and the fact that the guns of his fighter were unreliable. He approached the bomber staying behind the enemy tailplane to prevent the rear gunner from shooting at him, and fired at the enemy’s engines at a range of 30m. The bomber crashed to the ground, taking its crew with her. Lehtovaara had scored his first victory, and was promoted to the rank of Sergeant on the 23rd of March 1940.

LeLv (Fighter Squadron) 28 was transferred to Eastern Karelia (Olonets) in mid-March 1940 as part of the preparation for the late-winter offensive. Lehtovaara immediately scored a further victory – a DB-3. He also became an expert in “train-busting” attacks on the enemy freight trains on the Murmansk railway. The steam locomotives were disabled by shooting holes in the boiler, but the pilot had to defy the train’s AA guns to do this. In late March the Moranes had been upgraded with radio equipment, a rollover bar and seat armour, but the pilots were still relatively inexperienced as most of the more experienced pilots had been moved to squadrons with newer and more capable fighters. Lehtovaara was the only experienced pilot left, the others were novices. Due to the deficient pilot training the squadron was used mainly to assist the infantry with ground strafing and in train-busting attacks and attacks on enemy transport in the rear areas. Also the tactics of the squadron were not well thought out due to the level of inexperience at the command ranks and victories were few and far between, although there were also no losses to the enemy.

In April as the fighting intensified, Wihuri, Hawk, Fokker DXXI, Fokker G1, Heinkel He112, Miles M20, Hurricane, Avia B.534 and Fiat G.50 fighter pilots of the Ilmavoimat caused heavy losses to enemy bombers trying to attack the Finns, but the Morane pilots failed – the enemy came in low and wherever they were, they were always attacked at lunchtimes – even when they moved the time of lunch – and they never seemed to get into the air on time, even when warned by Fighter Control! But Lehtovaara was successful. He was mostly flying MS-327, with which he intercepted three DB-3’s on 3 April 1940 at Ilomantsi. He shot down two and damaged the third. Six days later (on 9 April) he shot down two SB-2’s and after a long dogfight a Soviet fighter. Later he would says that his first real dogfight taught him more than all the training he had been given. Lehtovaara received Senior Sergeant’s stripes on 23 April 1940. An air battle on the 9 May1940 (see details in another “Jätti” story) increased his score to 11 and got him promoted to Sergeant Major. On 12 May 1940 Lehtovaara and another Morane pilot were bounced by several Soviet fighters near Segezha. The other Morane pilot managed to retreat, but Lehtovaara (with MS-327) had to fight it out with a Soviet fighter pilot who was determined to take him on. Lehtovaara shot down his adversary while the other inactive enemy fighters were “watching the show”. The enemy pilots even allowed the victorious Morane escape. It was surmised that they were inexperienced trainees, who had lost their instructor.

The Morane Ace, Sgt. Urho Sakari Lehtovaara (nick-named by friends “Pikku-Jätti” – “Little Giant”) standing by the tail of his Morane Saulnier 406, MS-327, on the 9th of June 1940

On 5 June 1940 Lehtovaara managed to intercept a Soviet bomber on a reconnaissance mission at 7000m – without his oxygen mask. He fired at the photographing bomber from below, the Morane “hanging” on its propeller until the engine stopped. He managed to restart his engine before the two escorting fighters attacked him. In the ensuing dogfight Lehtovaara shot down one of them. Sergeant Major Lehtovaara was transferred to the new LeLv 34 in late June 1940, just as the newly formed squadron began to equip itself with the British-suppled Westland Whirlwind fighters. He belonged to the 3rd Flight commanded by Capt. Puhakka. The first victory that the ex-Morane pilot scored was a Soviet fighter on 19 July 1940. The well-equipped LeLv 34 was involved in heavy air battles against numerically superior enemy but due to the aircraft performance and the skills of the fighter pilots, consistently emerged from the battles unscathed and with numerous enemy aircraft shot down.

For example on 24 July 1940 Lehtovaara fought against unusually large odds. He had taken off at 12.40 hours from Kymi/Juurikorpi air base to test-fly his fighter aircraft after repair. At 12.47 the base was alerted: 15 Soviet bombers escorted by 19 Soviet fighters had been detected approaching Kotka. Major Luukkanen, the Squadron Leader, sent an order to Lehtovaara over the radio: “Attention Giant, fifteen bombers and nineteen fighters approaching Kotka from the South, intercept!” At that very moment Lehtovaara was approaching the runway with gear down. Without hesitation he interrupted the approach and accelerated to full power above the runway until he had picked up enough speed. Then he began to gain altitude to meet the enemy – two more ilmavoimat figherts were frantically being started on the base: Major Luukkanen himself and Sergeant Major Tani were coming to help. The defensive AA opened fire – the enemy bombers dived to attack. The leading bomber was hit by the AA fire and continued her dive into the sea.

Lehtovaara wrote in his battle report: “I attacked the enemy formation but was engaged by enemy fighters that tied me up in a dogfight lasting 20 minutes. I shot at three fighters, each of which shed large pieces and disengaged immediately. A fourth caught fire but the fire was extinghuised soon and the smoking plane was lost from my view before Someri Island. The pilot of the fifth enemy plane that I fired at in a turn was probably hit because enemy half-rolled and nose-dived in the sea about 15 km SE of Someri.” The battle ended as the enemy retreated. The ground crews and other personnel of the base were anxiously waiting. They could hardly believe their eyes as all three Ilmavoimat fighters returned. Lehtovaara parked his fighter and climbed out of the cockpit as the responsible mechanic ran to see what the pilot had done to his fine aircraft.

Lehtovaara paced here and there, cursing aloud at the small ammunition magazine capacity of the Whirlwind, trying to calm down. To their surprise, the mechanics did not find a single hole in the aircraft, just the radio antenna had disappeared. Major Luukkanen was grateful that it had been Lehtovaara who had been in the air as the alert was received. The man’s courage and sense of duty had no limit: without hesitation he had single-handedly attacked thirty-six enemy aircraft. Lehtovaara was the best pilot in the base to obey that order – and survive. Luukkanen had shot down a fighter himself, but Tani failed to score. However it was not this incident that Lehtovaara himself considered his toughest experience (please check “Jätti’s” two combat stories). On 29 July 1940 he was promoted to the rank of Air Master Sergeant (the highest NCO rank).

The Soviet offensive over July and August 1940 was a tough period for the Finnish armed forces, also for the Air Force. The enemy flew often in 100-plane+ formations and despite the constant heavy losses inflicted by the Ilmavoimat, there were always more Soviet fighters and a seemingly unended stream of bombers. There was enough light for flying for 24 hours per day up to mid-July, so the fighter pilots of Squadron 34 often had 19-hour days. In Summer 1940 Lehtovaara’s most successful day was the 2nd of August. At 20.00 hours that day 35 Soviet bombers dive-bombed the Lappeenranta Air Base, followed by a strafing attack by 40 bombers covered by dozens of escort fighters. 11 Hawls of LeLv 24, whose base was attacked, managed to scramble. LeLv 34, based at Taipalsaari a dozen km to the north-west, was asked to help, and sixteen Whirlwinds took off at 20.10 hrs, led by Ltn. Myllylä. Lehtovaara, one of the pilots, chased the bombers and managed to shoot down three in succession. The attackers lost fifteen bombers and one escorting fighter. One Whirlwind was found to be battle damaged on landing. On the 25th Augist, Lehtovaara shot down one Soviet fighter – which was his last victory of the Winter War, bringing him to a total of 44 1/2. He had been awarded the Mannerheim Cross on the 9th of August 1940.

Lehtovaara remained in the Ilmavoimat after the Winter War, was promoted and in mid-1944, when Finland declared war on Germany, he was Squadron Commanding Officer of LeLv 34, a command that he held until he retired from Ilmavoimat service in November 1946. He achieved another 31 victories against the Germans, although it was more than rumoured that a number of these were Soviet aircraft. However, Soviet or German, to the Ilmavoimat a kill was a kill and the only victories that were not counted were those against British or American aircraft, of which there were a small number towards the end of WW2 as Allied fighter pilots initially showed a lack of discernment when it came to identifying the Nazi Swastik vis-à-vis the Ilmavoimat’s Hakankreuz.

We can assume that “Jätti” was addicted to flying and in particular to air battles. The thrill a fighter pilot gets when fighting for his life is a stimulant that peacetime service could not offer. After the war, Lehtovaara returned to his home district. He was the owner-operator of a movie theater at Suomusjärvi near Salo when he suddenly died in 1949 at the age of 42.

Battle of the Moranes

It was the 9th of April 1940 in Eastern Karelia, Olonets. Early in the morning about 06.00, four MS-406 fighters of LeLv 28 were covering the advancing Finnish troops. The flight was led by Sr.Sgt. Urho Lehtovaara flying MS-304. The Finnish pilots saw an approaching formation of 18 Soviet fighters: Lehtovaara gave the order to attack the enemy. A “furball” ensued. The Soviet pilots were disturbed by their own numeric superiority, they were constantly in danger of colliding with each other, thus they had to watch for each other as much as for the Moranes. Also they were tempted to open fire at a long range in competition for targets.

The Finnish pilots knew what to do: they kept turning in one direction only and fired upon opportunity at close range. Lehtovaara scored the first victory, but immediately a section of three fighters managed to get behind his tail. But the rigid three-plane formation prevented the enemy wingmen making use of their superiority, the wing fighters fired into thin air as the leader fired at the Morane. After a while Lehtovaara managed to out-turn the three Soviet fighters and he fired into the engine of the leader. The Soviet fighter engine began to smoke, the fighter stalled and dived, the pilot bailed out.

Lehtovaara disengaged from the leaderless wingmen and checked the general situation. The other three Moranes were each fighting three to four enemies, without any apparent problems. Then Lehtovaara saw one Soviet fighter that tried to disengage and dived after him. Lehtovaara fired, but the salvo hit the enemy fighters armour, only alerting the pilot. The two fighters entered into a dogfight, trying to out-turn each other. The Soviet pilot was very skillful, Lehtovaara begin to consider disengaging. None of his hits had had any effect on the rear armour of the enemy. Then the Soviet pilot for some reason pulled a slow vertical roll, exposing the vulnerable belly of his fighter. Lehtovaara was prepared and his salvo hit the enemy’s engine. The enemy fighter caught explosively on fire and nose-dived to the ground with its pilot.

Now Lehtovaara called his scattered pilots and ordered a join-up. All three responded. Their total score was seven Soviet fighters, three of which were claimed by Lehtovaara. This battle was exceptionally successful for Moranes, planes often considered inferior due to their weak armament. However, it was a typical result of the air battles of the Winter War in terms of the overall outcome.

A Memorable Battle

In 1946 Jorma Karhunen, a fellow pilot and also a Knight of the Mannerheim Cross, met Urho Lehtovaara and asked him what had been the most memorable of his air battles. Lehtovaara declined to answer at first, but as Karhunen told him that he was collecting history, not looking for personal glorification of anyone, “Jätti” told about the 6th of March 1940 at Kotka. The Kymi air base had been made inoperational because of a heavy snowstorm on the 4th of March and it took two days to clear the snow completely from the runway. The 3rd flight of LeLv (Fighter Squadron) 28 had nine Moranes of which five were airworthy. On the 5th of March a ship convoy carrying war supplies had arrived through the ice in Kotka harbour and it was spotted there early next day by a reconnoitering Soviet bomber before two Moranes chased it away. Next day, in the afternoon of the 6th the enemy sent 27 bombers escorted by 12 fighters to destroy the ships in the harbour. The available Moranes were scrambled at 14.00 hrs. Major Luukkanen took off first, after him Sergeant Major Tani, then Air Master Sergeant Lehtonen. Sergeant Major Lehtovaara and Sgt. Lyly could start-up only a couple of minutes later since their fighters were not prepared for immediate take off.

Luukkanen and Lehtonen intercepted the first wave of nine bombers and shot down two before the escorting fighters intervened. The defensive AA guns fired indiscriminately at the aircraft, and the Soviet bombers released hastily their loads and turned away. Tani attacked one wave of the returning bombers head-on and fired at each one as he passed. He once was so close that he saw exploding 20 mm shells ripping holes in the fuselage of a bomber. Tani damaged five and shot down one. Lehtovaara chased the bombers that had been scattered by the defence, and shot down two stragglers at Someri Island before returning back to base to avoid contact with fighters. The total score for the five pilots was five bombers and three fighters. Major Luukkanen’s Morane had been badly damaged in the fuselage by a Soviet fighter. There were no other losses. No ships were hit.

The enemy made a new surprise attack three hours later with 12 bombers escorted by 17 fighters. The base was alerted by Sr. Sgt. Länsivaara who was on an ice reconnaissance mission. Again four Moranes took off to intercept. This time the escort fighters were doing their duty better and prevented the Morane pilots from getting more than one of the bombers. The Finnish fighters were soon dispersed and each pilot had to fight for himself without help from the others. Lehtovaara was engaged by a good fighter pilot, who kept his altitude and speed advantage by doing high yo-yo attacks at the low-flying Morane. Only the enemy’s shooting skill was not equal to his flying skill. The Soviet pilot did not spare ammunition but he fired at too long a range, and Lehtovaara kept evading quite easily. Staying calm and ready for a counterstrike the Finnish pilot noticed that the enemy pilot was losing his temper after ten minutes. Finally the enemy failed to pull up with full speed after a firing pass, allowing Lehtovaara to get behind the Soviet fighter in good range. One salvo from the cannon of the Morane, and the Soviet fighter dived in flames toward the Baltic ice.

Immediately four more Soviet fighters attacked, and all the pilots were equal to the first opponent. Lehtovaara was in great trouble now, because whenever he had dodged one attack, another enemy was already aiming at him. The Finnish pilot could not fly straight long enough to aim and shoot. Slowly the dogfighting fighters gained altitude in the course of the battle. Finally three of the enemies retreated, probably due to fuel shortage, but the fourth was hanging behind the tail of Lehtovaara’s Morane. The altitude was now about 3000m. Lehtovaara was getting exhausted and he felt he could not shake the enemy off without doing something unusual. So he half-rolled and nose-dived – the Soviet fighter followed. Lehtovaara turned the Morane with ailerons so that the setting sun shone him in the face and its glare combined with reflection from the ice impaired his vision. He dived as low as he dared at a final speed of nearly 900 km/h, then pulled out of the dive with two hands on the stick, blacking out. As the Finnish pilot regained his vision, he was flying a few meters over the rough Baltic ice. He turned and looked back to see the enemy – but all he could see was a column of smoke over the ice. Lehtovaara flew closer to inspect. His adversary had not pulled out of the dive in time, the Soviet fighter had touched the ice three times before the final impact.

Lehtovaara tested his guns – they were jammed. His radio was dead, and he felt great weariness when taking direction to the base. After landing he felt as if he were on a foreign planet, where he had no right to be. But for the mercy of God he and the Morane would have been a heap of rubble on the Baltic ice. However, this victory was not credited to him because later the wreck of the Soviet fighter could not be found on the ice – it had been snowed over. That day the 3rd Flight had scored thirteen confirmed victories at the cost of two damaged, repairable Moranes. Three dead and two living Soviet airmen were found on the ice. The men taken prisoners were Lt. Seraphin Pimenow, 20 years in age and Sergeant Major Vladimir Varschidskiy, 23 years, both from the 12th Guards’ Dive-bombing Regiment (12.Gv.PBAP). A dozen bombs had hit the town, destroying several houses and killing 6 civilians and five soldiers. The ships in the harbour had not been damaged in either attack.

The same action has been described in the official history of the Aviatsiya VMF (Moscow, 1983).

We are told that on the 6th of March 1940 Kotka harbour was attacked once by 20 bombers escorted by 18 Fighters. The defence sent six Moranes and four Hawks to intercept. In the ensuing battle the Soviets shot down five Moranes and one Hawk. One Soviet bomber and three fighters were damaged by the defenders. (That is, there were no actual Soviet losses). Several ships were sunk.

You may notice some differences between the Soviet and Finnish stories. The Soviet version of the day might not have been properly researched, and facts from an attack on another harbour on the southern coast of the Gulf of Finland may have been introduced into the story.

The Fall of France and the MS 406’s for Finland

With the fall of France, the twenty remaining MS 406s of the fifty promised would not be delivered. However, despite the ill-feeling between the two countries that had resulted from the Helsinki Convoy and the seizure of the Finnmark, Germany would go on to trade 45 MS 406’s and 11 MS 410’s between 1941 and 1942 for payment in Nickel, which Finland continued to sell or trade to Germany up until the declaration of war in April 1944. By this point the fighters were hopelessly outdated, but until american lend-lease supplies started to flow in mid-1943, the Finns continued to be desperate for serviceable aircraft. Their own aircraft production remained limited and while the aircraft that were produced in Finland were superbly capable and of high quality, there were limits on Finnish industrial capacity which, simply, could not be exceeded. The Finns continued to acquire what they could – and with the MS 406’s / 410’s, they decided to start a modification program to bring all of their examples to a new standard.

The young Valtion Lentokonetehdas (VL) aircraft designer Aarne Lakomaa turned the almost-obsolete “MS” into a first rate fighter, the Mörkö-Morane (Bogey or Ogre Morane). Note: Aarne Lakomaa (1914–2001) was a Finnish aircraft designer. Born in Finland, Lakomaa graduated from Helsinki Polytechnic. He became famous for fitting Finnish-manufactured Hispano-Suiza 12Y engines to the semi-obsolete French Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 fighters, thereby creating a first rate fighter, the Mörkö-Morane. Lakomaa remained with Valtion Lentokonetehdas after the end of WW2 as an aircraft designer and was involved in the development of the joint-venture between VL and Saab, where he was involved with the design of the VL-Saab 35 Draken and VL-Saab 37 Viggen fighters. He would later move to Saab where he headed R&D, designing a number of prototypes, including a rocket propelled interceptor, nuclear weapon carriers, replacements for the Draken and Viggen, and a supersonic business jet.

The photo is of an Enso-Gutzeit Savonlinna shooting competition team. From right, accountant Laitaatsillan Aki Haltia, (a very youthful) Aarne Lakomaa, Mikko Kolehmainen, Mauno Laitinen, District Supervisor Eino Pesonen and Office Manager Toivo Huotari. Competitions were held Pankakoski.

Powered by the Finnish-manufactured license built Hispano-Suiza HS12Y engines of 1,100 hp (820 kW) with a fully adjustable propeller, the airframe required some local strengthening and also gained a new and more aerodynamic engine cowling. These changes boosted the speed to 326 mph (525 km/h). Other changes included a new oil cooler, the use of four belt-fed machineguns and the excellent license-built HS 20mm cannon in the engine mounting. Work on the modifications had begun almost as soon as the Winter War had ended and the prototype of the modified fighter, the MS-631, made its first flight on 25 January 1941. The results were startling: the aircraft was 40 km/h (25 mph) faster than the original French version, and the service ceiling was increased from 10,000 to 12,000 m (32,800 to 39,360 ft). Conversion work proceeded as quickly as could be achieved and by late 1942, all surviving Morane-Saulnier’s had been converted. They would however be relegated to the Ilmavoimat Reserve by mid-1944 and would not see combat against the Luftwaffe.

A bit of background on the MS 406

The M.S.406 had been designed in 1935 by the French aircraft company, Morane-Saulnier. Morane-Saulnier had a long history of producing warplanes dating back to the pre-World War I years but in the inter-war period, they had concentrated on civil designs. The aircraft was a departure for them, their first low-wing monoplane, first enclosed cockpit and their first with retracting gear. The first M.S406-1 prototype flew on 8 August 1935 but development was slow and the second protype didn’t fly until 20 January 1937, almost a year and a half later. At this stage the fighter could reach a speed of 275 mph (443 km/h), which was fast enough to secure a French Air Force order for a further 16 pre-production prototypes, each including improvements on the last version. The two main changes were the inclusion of a new wing structure that saved weight, and a retractable radiator under the fuselage. Powered by the production 860 hp (640 kW) HS 12Y-31 engine, the final design achieved 304 mph (489 km/h). Armament consisted of a 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS-9 cannon with 60 rounds, which fired through the piston banks in the engine and two belt-fed 7.5 mm MAC 1934 machine guns in the wings with 300 rounds each.

The French Armée de l’Air placed an order for 1,000 airframes in March 1938. Morane-Saulnier was unable to produce anywhere near this number at their own factory, so a second line was set up at the nationalized factories of SNCAO at St. Nazaire converted to produce the type. Production for the Armée de l’Air began in late 1938, and the first production example flew on 29 January 1939. Deliveries were hampered more by the slow deliveries of the engines than airframes. By April 1939, the production lines were delivering six aircraft a day, and when the war opened on 3 September 1939, production was at 11 a day with 535 in service with the French Armée de l’Air (we can see then that the thirty supplied to Finland used around 3 days of manufacturing time). Numerically it was France’s most important fighter during the opening stages of World War II but the French version was under-powered, weakly-armed and lacked full armour protection when compared to its contemporaries in the Luftwaffe and the RAF.

The French take further concrete steps to assist Finland

However it was not until late March 1940, when it was apparent that Finland was fighting with tremendous effect against the might of the Soviet Union, that further concrete steps to assist Finland were actually taken. This was however only after the resignation on 20th Match of the French Prime Minister, Édouard Daladier – a resignation that was due (in part) to his failure to aid Finland’s defence in anything more than a cursory fashion. Daladier’s successor, Paul Reynaud, was elected Premier by only a single vote with most of his own party abstaining; over half of the votes for Reynaud came from the French Section of the Workers’ International (SFIO) party. With so much support from the left – and the opposition from many parties on the right – Reynaud’s government was especially unstable; with many on the Right demanding that Reynaud attack not Germany, but the Soviet Union. To alleviate the pressure from the Right, Reynaud would take immedite steps to assist Finland in her struggle for survival with the Soviet Union – and the increasingly favorable news from Finland would assist him in this – the capture of Murmansk by the Finns and the success of the Finnish Winter Offensive in Eastern Karelia dominated the headlines in Paris and London.

The Finn’s fighting successes were in direct contrast to the “Phoney War” being fought along the border between France and Germany. At the same time as Reynaud used aid to Finland to satisfy the French Right, he also abandoned any notion of a “long war strategy” based on attrition. Reynaud entertained suggestions to expand the war to the Balkans or northern Europe; he was instrumental in launching the allied campaign in Norway, though it would end in failure. Britain’s decision to withdraw on 26 April would prompt Reynaud to travel to London to personally lobby the British to stand and fight in Norway and to attempt to persuade the Finnish Ambassador to lobby the Finnish Government to go beyond a pre-emptive seizure of the Finnmark region of Norway and join the fight against Germany in Norway. In both of these he would be unsuccessful. However, in late March 1940, Reynaud was successful in having immediate steps taken to supply material aid to Finland. In almost his first decision to be taken after assuming the reins of power, he acted to send military supplies to Finland, transferred two destroyers of the French Navy to the Finns and arranged the dispatch of a number of aircraft. In addition, he would dispatch Polish airmen and soldiers to Finland – a move which some Poles objected to at the time, as they wished to fight the Germans, but for which they were thankful for after the Fall of France – inadvertently ensuring that they remained able to fight on after France fell, unlike so many of their comrades.

This concrete assistance came in the shape of the transfer of two older L’Adroit Class Destroyers (La Railleuse and Le Fortune) to the Finnish Navy, to be used for trans-atlantic Convoy Escort duties. The Adroit class destroyers were a group of fourteen French navy destroyers (torpilleur) laid down in 1925-6 and commissioned from 1928 to 1931. They were the successors to the Bourrasque class, with the same armament, but being slightly heavier overall. They displaced 1,378 tons (2,000 fully laden), had a length of 354 ft, a beam of 32ft 3in and a draught of 14ft 1in, a speed of 33 knows (38mph), a crew of 142 men and were armed with 4 x single-barreled 130mm gun turrets, 2x37mm guns, 2×13.2mm machineguns and 6 torpedo tubes. They were relatively modern destroyers and there was some objection from the French Navy with regard to handing them over to the Finns. Reynaud however would overrule this and the two destroyers would enter service with the Merivoimat in early April 1940. There would be little time for the Merivoimat crews to familiarize themselves with the ships before taking them into action. They were also under-equipped with AA guns and while the Finns had fitted a number of additional machine-guns to the La Railleuse, in the event these proved to be insufficient protection against the Luftwaffe.

These two destroyers were steamed to Lyngenfiord in late March 1940 as escort for two French cargo ships carrying military supplies and three passenger ships packed with Polish troops from the Polish Army in France. Entering service with the Merivoimat in February 1940, La Railleuse would be sunk by the Luftwaffe in April 1940 after being hit a number of times by bombs as she escorted the Helsinki Convoy through the southern Baltic. Le Fortune would serve as an Atlantic Convoy escort for Finnish merchant ships throughout WW2, based from Lyngenfiord. make her more suitable for Atlatic escort duties, the Finnish Navy removed two gun turrets (#’s 2 and 3) and fitted depth charge launchers together with storage racks. She would first see Finland in August 1945, going on to serve with the Merivoimat in the Baltic until 1950, after which she was handed over to the Estonian Navy. She would serve as the Estonian Navy’s flagship until 1962, when she was scrapped.

The Arrival of the Potez 631’s

However, the next tangible aid to arrive in Finland was actually a single squadron of aircraft. Arriving on the 31st of March 1940 after being flown as a unit was a single squadron of some 20 Potez 631’s.

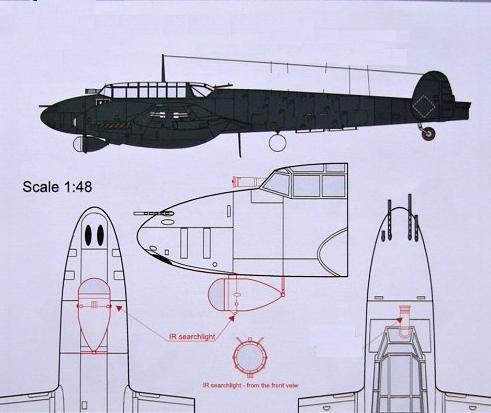

They were flown by Polish Air Force personnel serving with the French Air Force on a route from France to the UK, and thence to Norway, then across Sweden to Finland, The Polish ground crew and parts for the aircraft were dispatched by ship, only linking up with the aircraft some 6 weeks later, but the Potez 631’s would enter service immediately with groundcrew patched together from whatever Ilmavoimat personnel could be made available. There were different versions of the Potez 630 – the Potez 631’s delivered to Finland were in fact intended as night-fighters, similarly to the RAF’s Bristol Blenheim or the German Messerschmitt Bf 110.

The Potez 631’s supplied to Finland had a maximum speed of 264mph, a range of 932 miles and a service ceiling of 27,885 ft. They were armed with 2x fixed, forward-firing 20mm cannon in gondals’s under the fuselage and 1x flexible, rearward-firing 7.5 mm MAC 1934 machine gun. They could also carry 4x 50 kg (110 lb) bombs in a small internal bombbay. On bringing the aircraft into service as night fighters, the Ilmavoimat replaced the internal bomb bay with an additional fuel tank, increasing the range and endurance and eliminated the rear gunner and machinegun, instead adding a radio operator/navigator in the middle seat (later, with the new radar, this would become the radar operator position).

The Ilmavoimat at the time had no night-fighters, the Potez 631’s performance was such that it was regarded as unsuitable for use as a day-fighter and its small bombload was such that it was regarded as no use for ground-attack missions. As such it was relegated to use as a night-fighter – and it was the availability of this aircraft that would provide the impetus for the trial use of a nose-mounted active-infrared searchlight (used to illuminate the target) while a Nokia-designed and developed display unit in the cockpit made the target visible.

Sketch showing the location of the IR Searchlight beneath the nose of the Potez 631 and the IR Viewer location

This equipment was based on the Infrared searchlights and viewers used by the Maavoimat’s night-fighting tanks – and as such was readily available, quickly adapted and rapidly installed. By late May 1940, the Ilmavoimat’s first and only infrared equipped night-fighter squadron was up and running – unfortunately only in late May, by which time the long winter nights were fast fading. However, when vectored onto a target by Fighter Control, it occasionally proved possible for the fighters to actually illuminate the target and half a dozen Soviet bombers on night-bombing missions were successfully show down by the time the war ended.

After the Fall of France, significant numbers of Armée de l’Air Potez 630’s had fallen into German hands and many were impressed by the Germans, mostly to be used in liaison and training roles. The Ilmavoimat would go on to purchase some 40 ex- Armée de l’Air Potez 630’s in late 1941, after Finland’s relationship with Germany had improved somewhat from the somewhat glacial post-Helsinki Convoy chill. And again, the Finns used the supply of Nickel to Germany to exert pressure. These additional aircraft would be refurbished, re-engined, re-armed and over 1942 and 1943 would be equipped with Nokia-design and developed night-fighter aircraft radar. With new and more powerful engines, they would remain in use as night-fighters with the Ilmavoimat until the end of WW2, although by then they would not be the primary night-fighter type.

Somewhat incidentally, Finland’s strength and capabilities in the air would be augmented greatly by Polish Volunteers for the Ilmavoimat through the Winter War, especially in the last months of the War from June to September 1940. In part, Finland benefited from the pre-war agreements with Poland whereby each country agreed to act as a refuge for the other’s armed foirces in the event of war and if possible. The rescue by the Finns of many thousands of Polish military personnel from Latvia and Lithuania had strengthened this relationship, and that so many of these Poles volunteered to fight for Finland against the USSR further stregthened the mutual regard and feelings of gratitude and respect.

A Nokia-designed and developed Infrared display unit in the cockpit of the Potez-631 made the target visible.

After the collapse of France in May 1940, a large part of the Polish Air Force contingent in France was withdrawn or escaped to the United Kingdom. However, the RAF Air Staff were not willing to accept the independence and sovereignty of Polish Air Force personnel. Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding later admitted he had been “a little doubtful” at first about the Polish airmen. The British government informed General Sikorski that at the end of the war, Poland would be charged for all costs involved in maintaining Polish forces in Britain. Plans for the airmen greatly disappointed them: they would only be allowed to join the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, wear British uniforms, fly British flags and they would be required to take two oaths, one to the Polish government and the other to King George VI of the United Kingdom; each officer was required to have a British counterpart, and all Polish pilots were to begin with the rank of “pilot officer”, the lowest rank for a commissioned officer in the RAF. Only after posting would anyone be promoted to a higher grade. Because of that, the majority of the Polish pilots, much more experienced than their RAF counterparts, had to wait in training centres, learning English Command procedures and language, while the RAF suffered heavy losses due to lack of experienced pilots.

This obviously did not go down well with either the Polish Airmen, General Sikorski or the Polish-government-in-exile. Thus, in discussions that were ongoing between Finland and the Polish-government-in-exile, when Finland asked for help from the Poles to provide personnel for the additional aircraft they were bringing into service, and offering equivalent ranks in the Ilmavoimat, together with the formation of 100% Polish squadrons flying under the Polish Flag, the Polish-government-in-exile was quick to agree. Personnel for four squadrons were formed up and moved to Finland in late June 1940. Equipped with aircraft by the Ilmavoimat that ahd been purchased from the USA, the Polish squadrons quickly became effective. As with their countrymen already in Finland, it was found that there flying skills were well-developed from the Invasion of Poland and their time in France and the Polish pilots were regarded as fearless and sometimes bordering on reckless. In other words, very similar to the Finns. Such was the success of these units that the Finns requested more volunteers, but by this stage the RAF, desperately short of personnel and now impressed by the performance of the Polish airmen they had slowly accepted, refused permission.

However, the RAF would still experience some communications problems…..

Some background on the Potez 631’s

The Potez 630 and its derivatives were a family of twin-engined aircraft developed for the French Armée de l’Air in the late 1930s. The design was a contemporary of the British Bristol Blenheim and the German Messerschmitt Bf 110. The original Potez 630 was built to meet the requirements of a 1934 heavy fighter specification which also resulted in the successful Breguet 690 series of attack aircraft. The prototype first flew in 1936 and proved to have excellent handling qualities. It was a pleasant-looking three-seater aircraft with an all-metal stressed-skin, cantilever monoplane with a retractable landing gear and twin engines, with efficient aerodynamic lines and twin tailplanes. The long glasshouse hosted the pilot, an observer or commander who was only aboard if the mission required it, and a rear gunner who manned a single flexible light machine gun.

Only very minor changes were required before the aircraft was placed in production with an order for 80 placed in 1937. Simultaneously 80 Potez 631 C3 fighters were ordered, these having Gnome-Rhône 14M radial engines rather than the Hispano-Suiza 14AB10/11 of the Potez 630. Fifty additional Potez 631s were ordered in 1938 (of which 20 were diverted to Finland). The Potez 630’s engines proved so troublesome that most units had re-equipped with the Potez 631 engines before WW2 began. The Potez 631 was an ineffectual interceptor, slower than some German bombers and 130 km/h slower than the Bf 109E, although it continued in service until the armistice. The Potez 633 exported to Greece and Romania saw more extensive service, in limited numbers. The Romanians used them against the USSR and the Greeks against Italy. A small number of Potez 633’s originally destined for China were commandeered by the French colonial administration in Indo-China and saw limited action in the brief French-Thai War in early 1941.

More than 700 Potez 630’s of various models were delivered by June 1940, with some 220 destroyed or abandoned, despite the addition of extra machine gun armament; the heaviest losses of any French type. Production was resumed under German control and significant numbers were impressed by the Germans, mostly for use in liaison and training roles.All members of the family shared pleasant flying characteristics. They were well designed for easy maintenance and later models had a heavy armament for the time (up to 12 light machine guns for the Potez 63.11). They were also quite attractive aircraft. Although not heavily built they proved capable of absorbing considerable battle damage. Unfortunately the Potez 630 family, like many French aircraft of the time, simply did not have sufficiently powerful engines to endow them with an adequate performance. In the stern test of war they proved easy meat for prowling Messerschmitts, like their British contemporaries, the Fairey Battle and the Bristol Blenheim. Their similarity to the Bf 110 (twin engines, twin tail, long “glasshouse” canopy) was sufficient that some were apparently lost to “friendly fire”. Unlike many contemporary French aircraft, production of the Potez aircraft was reasonably prompt and the first deliveries were effected before the end of 1938. The 630 had been designed with mass production in mind and as a result, one Potez 630 was cheaper and faster to manufacture than one Morane-Saulnier MS.406. As production tempo increased, a number of derivatives and experimental models were also developed.

A typical feature of the 630 and 631 was the frontal armament, which originally consisted of two 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS.404 cannons in gondolas under the fuselage, though sometimes one of the cannons was replaced by a MAC 1934. Later in their career, 631s received four similar light machine guns in gondolas under the outer wings, though it was theoretically possible to fit six. In combat, the 630’s proved very vulnerable, despite being protected with some armour and basic self-sealing coating over the fuel tanks. As a secondary light bomber capability was part of the requirement (though it was rarely if ever used), the fuselage accommodated a tiny bomb bay, carrying up to eight 10kg-class bombs. This bomb bay was replaced by an additional fuel tank in late examples. Additionally, two 50kg-class bombs could be carried on hardpoints under the inner wings.

The dispatch of the Polish Second Infantry Fusiliers Division from France to Finland

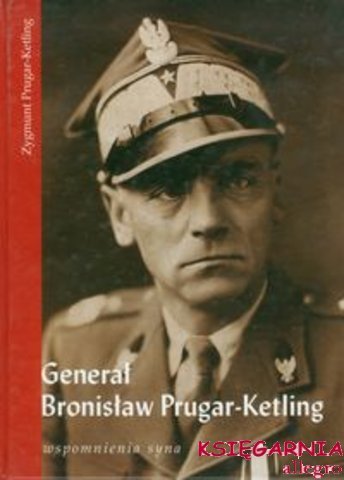

Besides the two cargo ships that were dispatched with their sizable cargo of Caudron-Renault C.714 fighters (more on these below) together with munitions and the artillery pieces that the Maavoimat desperately needed, the small convoy also carried the Polish Second Infantry Fusiliers Division (15,830 soldiers) commanded by Brigadier-General Bronisław Prugar-Ketling.

Brigadier-General Bronisław Prugar-Ketling (2 July 1891, Trześniów, Subcarpathian Voivodeship – 18 February 1948, Warsaw)

Brigadier-General Bronisław Prugar-Ketling (2 July 1891, Trześniów, Subcarpathian Voivodeship – 18 February 1948, Warsaw) was a member of the Polish Military Organisation in World War I, he later served in the Polish Blue Army. He went on to fight in the Polish-Soviet War. During the German invasion of Poland he commanded the Polish 11th Infantry Division in the Karpaty Army. Under his command the 11th I.D. defeated the mechanized groups of the SS “Germania” Regiment in the Battle of Jaworów. After escaping from Poland he arrived in France and was appointed to command the Second Infantry Fusiliers Division in “Sikorski’s Army” (the Polish Army in France). Eager to fight the Germans, he reluctantly acquiesced to the French decision to send his Division to Finland.

The Division had been assigned as part of the French reserves of the XXXXV Corps, but the French were more than happy to get rid of the Poles, whom they regarded as trouble-makers who had brought the Germans down on their heads. For their part, the Poles could not understand why the French did not want to fight. Thus the French were happy to dispatched considerable numbers of Poles, equipped by the French, to Finland.

In his Biography, Prugar-Ketling was later quoted as saying: “the French decision was the luckiest moment in my life. If the French had not decided to send my Division to Finland, I would have been trapped in France along with my men and we would have gone the way of so many other brave Polish soldiers, fighting and dying for a France that had already surrendered in all but word. With the Finns, were were able to keep on fighting, both to revenge oursevles on the Red Army for stabbing us in the back in 1939 and to defeat the Germans and go on to ensure Poland remained free.”

The Polish Second Infantry Fusiliers Division would arrive in Finland via Lyngenfjiord in early April 1940 and would be moved immediately to the Karelian Isthmus as a Reserve Division for the Maavoimat’s spring offensive. The Division would remain in Finland for the Winter War and for a time thereafter, before being shipped to the Middle East where they would fight with the British Army in the Desert War.

In late 1943 they would return to Finland, going on to take part in the Maavoimat’s Invasion of Estonia in early 1944 and then fighting their way southwards along the Baltic peripheral to Poland as part of the joint Finnish-Polish-Allied Army under the overall command of Marshal Mannerheim. The most well-known of the Second Infantry Fusiliers Division’s actions would be their move into Wilno (Vilnius) in the immediate aftermath of the successful Operation Ostra Brama (Operation Gate of Dawn), conducted by the Polish Home Army. Operation Ostra Brama had begun on 7 July 1944, as part of the Polish national uprising, Operation Tempest.

On 12 June 1944 General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, Commander-in-Chief of the Home Army, issued an order to prepare a plan of liberating Wilno from German hands. The Home Army districts of Vilnius and Navahrudak planned to take control of the city before the Soviets could reach it and in anticipation of the Maavoimat reaching them before the Red Army. In this, the Tehran Conference of November 1943, where Finnish Intelligence had gather evidence that Britain and the USA had agreed to the manipulation of the border between Poland and the USSR, was a key factor in the decision to laucnh the uprising. Both the Finns and the Polish Government-in-Exile were well aware of the concessions made to the USSR by Roosevelt and Churchill concerning post-war Poland. The USSR’s ruling triumvirate wished for an area in the Eastern part of Poland to be added to the USSR, and for the border to be lengthened elsewhere in the country. And to the shock of the Poles, Roosevelt and Churchill had agreed to this demand, agreeing that Poland’s borders would lie along the Oder and Neisse rivers and the Curzon line. In addition, Churchill and Roosevelt had also consented to the USSR setting up puppet communist governments in Poland, Czechoslovakia, the Baltic states, Romania, and other Eastern European countries. While the Polish government-in-exile in London had protested bitterly, the Finns were, through bitter experience of the duplicity of the Great Powers, rather less inclined to protest and rather more inclined to take matters into their own hands.

A group of Polish soldiers from the Second Infantry Fusiliers Division sings Dąbrowski Mazurka, the national anthem of Poland, prior to their departure for Finland.

And so it was that despite the large Allied presence with the Maavoimat in the Baltic, the Finnish High Command kept the Allied Units at the front fighting the Germans while Finnish and Polish units fought on the left of the offensive, where they could gain their own objectives. Thus, wherever possible German units were simply cutoff and bypassed as the Maavoimat moved to ensure they held the old Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian borders – as indeed they managed to do. And Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian army units werer rapidly raised and equipped from stockpiled lend-lease equipment (intended by the americans for the Finnish Army, but the Finns preferred to keep their own equipment and used the american equipment to fit out the Divisions of new volunteers – and also the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian units that had been fighting with the Germans but who promptly changed sides when their homelands were liberated.

The Commander of the Home Army District in Wilno, General Aleksander Krzyżanowski “Wilk”, decided to regroup all the partisan units in the northeastern part of Poland for the assault, both from inside the city and from the outside. The starting date was set for 7 July. Approximately 12,500 Home Army soldiers attacked the German garrison and managed to seize most of the city center. Heavy street fighting in the outskirts lasted until 14 July. In Vilnius’ eastern suburbs, the Home Army units initially cooperated with reconnaissance groups of the Soviet 3rd Belorussian Front. General Krzyżanowski wanted to group all of the partisan units into a re-created Polish 19th Infantry Division. However, the advancing Red Army entered the city on 15th July and the NKVD promptly started to intern all Polish soldiers. The internees, almost 5,000 officers, NCOs and soldiers, were sent to a provisional internment camp in Medininkai, a Vilnius suburb.

Battle of Vilnius. Soviet Red Army and Polish Armia Krajowa Soldiers patrolling in Vilnius, July 1944. The orthodox church of Vilnius is visible in background. The soldiers of the Second Infantry Fusiliers Division considered the liberation of Wilno and the freeing of their Home Army comrades from the NKVD as the highlight of their war. By this time the Polish and Maavoimat fighting troops were well aware of what had happened in the Soviet-occupied Baltic States during the Soviet occupation and to the Polish Officers in Katyn Forest in April and May 1940. “Allies” or not, no NKVD member could expect to survive a meeting with Maavoimat or Polish units – and as units of the Polish Army moved southwards into the rear of the 3rd Belorussian Front, many did not. And with the constant air cover and close air support provided by the Typhoons and Spitfires of the Polish Air Force and the fighters and fighter-bombers of the Ilmavoimat, the general attitude towards any Red Army unit that looked askance was “try it”. When accompanied by a flight of Polish Air Force Typhoons or the even more fearsome Ilmavoimat G1’s with their loads of bombs, rockets, napalm and cannon, there were generally no takers. And of there were takers, there were generally no survivors.

And Poles still remembered the Soviet stab in the back of September 1939….

Ballada wrześniowa (September Ballad) Lyrics – Jacek Kaczmarski

Długośmy na ten dzień czekali – We have waited for this day

Z nadzieją niecierpliwą w duszy – With impatient hope in our souls

Kiedy bez słów Towarzysz Stalin – For the moment when Comrade Stalin will silently

Na mapie fajką strzałki ruszy. – Move the arrows on a map with his pipe

Krzyk jeden pomknął wzdłuż granicy – One scream sounded along the border

I zanim zmilkł zagrzmiały działa – Before it stopped

To w bój z szybkością nawałnicy – The cannons had roared with the speed of a storm

Armia Czerwona wyruszała.- The Red Army had set off

A cóż to za historia nowa? – What is the story again?

Zdumiona spyta Europa,- A surprised Europe asked.

Jak to? To chłopcy Mołotowa – You do not know? It is Molotovs Boys

I sojusznicy Ribbentropa.- Ribbentrops allies.

Zwycięstw się szlak ich serią znaczy – A series of victories in their wake

Sztandar wolności okrył chwałą – Their flag of freedom covered in glory

Głowami polskich posiadaczy – The heads of the Polish possessors

Brukują Ukrainę całą. – Were used by them to pave the Ukraine

Pada Podole, w hołdach Wołyń – Padolia falls. Volhynia salutes!

Lud pieśnią wita ustrój nowy, – The people greet the new system with song

Płoną majątki i kościoły – The manors and churches are burning

I Chrystus z kulą w tyle głowy. – And the Christ has a bullet in the back of his head

Nad polem bitwy dłonie wzniosą – On the battlefield they will raise their hands

We wspólną pięść co dech zapiera – In a shared fist which takes the breath away

Nieprzeliczone dzieci Soso, – The countless childen of Soso

Niezwyciężony miot Hitlera. – Hitlers invincible litter

Już starty z map wersalski bękart, – Versailles bastard is wiped off the map

Już wolny Żyd i Białorusin – Jew and Byelorussian are set free

Już nigdy więcej polska ręka – Polish hand will nevermore

Ich do niczego nie przymusi. – Force them to do anything

Nową im wolność głosi “Prawda” – Pravda preaches their new freedom to them

Świat cały wieść obiega w lot, – The whole world is quickly informed

Że jeden odtąd łączy sztandar – That from this day there is one banner

Gwiazdę, sierp, hakenkreuz i młot. – Star, Sickle, Hammer and Swastika

Tych dni historia nie zapomni, – History will not forget these days

Gdy stary ląd w zdumieniu zastygł – When the old continent froze in surprise

I święcić będą nam potomni – And our descendants will celebrate

Po pierwszym września – siedemnasty. – After the first of September – the Seventeenth

I święcić będą nam potomni – And our descendants will celebrate

Po pierwszym – siedemnasty. – After the first of September – the Seventeenth

Soviet Backstabbing – July 1944

On 16th July the HQ of the 3rd Belorussian Front invited Polish officers to a meeting with the intent of arresting them. The local Home Army HQ had been in communication with the Maavoimat throughout the uprising but despite this, there was still a certain amount of shocked surprise at the betrayal by the Red Army. A secret NKVD/NKGB report dated July 17, 1944, from Lavrenti Beria to Litvonov, Molotov, Antonov and Zhadanov reveals the extent of the Soviet conspiracy against Polish forces. The following is an English translation:

July 17, 1944, Moscow

L. Beria to M. Litvonov, V. Molotov, A. Antonov, A. Zhdanov

Forwarding report(s) of [Ivan] Serov and I. Tcherniakovsky

[Concerning] Arrest of Lt. Col. Aleksander Krzyżanowski, and planned disarming of Polish [Armia Krajowa – Home Army] military formations.

Following information was received today from Comrade Tcherniakowsky:

The so-called Major-General “Wilk” / “Kulczycki” was summoned today. Wilk was told that we are interested in the locations of Polish formations, and that it would be prudent that our officers were familiar with them. Wilk agreed, and gave us 6 such locations, where his regiments and brigades are stationed. Additionally, we expressed our interest in his officers’ core, and proposed that he gathers all regimental and brigade commanders, their second in command, and chiefs of staff. “Wilk” also agreed to that, issued the necessary orders, and gave them to his communications officer, who immediately left for his headquarters.

After that, “Wilk” was disarmed [and arrested]; present at the time was a captain – the Chief of Staff who represents [the Polish] Government in London, who attempted to draw his side arm in order to resist, he cocked his gun, but was disarmed [and arrested as well]. Taking under consideration, that we received locations of Polish [Home Army] formations, the following operations’ plan was established

1) Experienced generals and People’s Commisars for the State Security of NKVD were dispatched in order to approach the Poles and to investigate [further].

2) At the same time, units of the 3rd Belarusian Front were dispatched to disarm the Poles.

3) Today, at 1900-hours, a Border Security unit, as well as the leadership cadre of men and women of the NKVD were dispatched to disarm the [Polish] officers’ cadre.

4) Tomorrow, on 18th July, at 4 o’clock in the morning, units designated to disarm the Poles will be move to their deployment positions, will receive orders, and will begin the operation. They will report about the results of the operation.

The Maavoimat reacted with an aggressiveness that brought the Soviet moves to an abrupt halt. The Second Infantry Fusiliers Division, supported by a Polish Armoured Regiment and squadrons of the Polish Air Force moved towards Wilno, eliminating any Red Army units that attempted to resist them and seizing and disarming those few that did not. Detachments of the Division headed straight for the provisional internment camp in Medininkai. The NKVD’s Battalion 32, which had been guarding the Poles and interrogating them to determine which were to be sent to the USSR, had begun executing Officers and NCO’s on news of the Polish Division’s approach. However, they had only just begun when Polish armoured and mechanized units roared into the camp and began their own extermination program.

In the subsequent fighting in and around Wilno, some 6,000 Red Army soldiers and NKVD personnel were killed, while some 12,000 Red Army soldiers were wounded and subsequently handed over to the Red Army after fighting ended. No NKVD wounded were available to be handed over. Remnants of the Red Army units in Wilno retreated into the nearby Rūdininkai Forest. They were soon discovered by Ilmavoimat air reconnaissance and surrounded by the Polish Home Army. Red Army Commanders decided to split their units and try to break through to the Red Army but most were caught and interned. The Second Infantry Fusiliers Division and the newly formed Polish 19th Infantry Division under General Krzyżanowski would hold the Polish areas around Wilno in strength until the end of WW2, eventually moving up to the pre-war Polish border. Other units of the Polish Army would move southwards into the rear of the 3rd Belorussian Front in strength while their advance towards East Prussia was cut off by Maavoimat Divisions surging south.

The Soviet High Command would reluctantly acqueisce to the Maavoimat’s seizure of north-eastern Poland and move their Divisions southwards in a move to seize southern Poland rather than enter into open conflict with the Finnish Army. This would lead to some post-war difficulties.

General Aleksander Krzyżanowski (known as “Wilk”, “Wesołowski”, “Dziemido”, “Jan Kulczycki”), was born in Bryansk and was conscripted into the Russian Army during the First World War, where he first started to specialize in artillery. After Poland regained independence in 1918 he joined the Polish military, and fought in the Polish-Soviet War where he distinguished himself in 1919 receiving the Krzyż Walecznych medal, and in January 1920 he took part in the heavy fighting at the Battle of Daugavpils. During the interwar period in the Second Polish Republic he further continued his military career. At the time of the Nazi invasion of Poland (September 1, 1939) he was commanding the 26th Regiment of Light Artillery, attached to the Polish 26th Infantry Division, part of the Army Poznań under General Tadeusz Kutrzeba. His unit was destroyed during the battle of Bzura.

Soon afterward he organized a partisan unit at Świętokrzyskie Mountains, but after this unit was defeated by the Germans he arrived in Warsaw by late October, and joined the first Polish resistance organizations, the Służba Zwycięstwu Polski. By November he was assigned to Wilno (now known as Vilnius, Lithuania), at the same time occupied by the Soviet Union which divided Poland with the Nazi Germany according to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. The SZP soon transformed into the Związek Walki Zbrojnej. When in April 1941 the Soviet NKVD arrested the commander of the ZWP in the Vilnius region, General Nikodem Sulik, it was Krzyżanowski who de facto replaced him, and his position was officially confirmed by General Stefan Rowecki in August. In 1942 ZWP was transformed into Armia Krajowa (AK).

Krzyżanowski attempted to build a larger anti-German coalition and issued explicit orders that no ethnic group, including Jews, should be mistreated. He also opened negotiations with the representatives of the Lithuanian and Belorussian resistance but these proved fruitless. The negotiations with the Soviets initially lead nowhere as well. The Soviet Union aimed to ultimately regain control from Germany over the territories the USSR had annexed from Poland in 1939 and the Politburo’s aim was to ensure that an independent Poland would never reemerge in the postwar period. The relationship between the Soviets and the Sikorski Polish government in exile, formally a commanding force of the AK, was strained at best, especially in the wake of the evidence of the mass execution of the Polish POW officers by the Soviets that were in 1943 widely publicized by the Nazis.

With Soviet partisans increasingly engaged in terror against the local population and attacking Polish Home Army units, local AK commanders considered the Soviets just another enemy. As ordered by Moscow on June 22, 1943 the Soviet partisans started an open fight against both the German forces and the local Polish Home Army partisans. In January and February 1944, in the wake of growing hostilities between the Soviet partisans and the AK forces, Krzyzanowski conducted a series of negotiations with Germans. Following negotiations with the Nazi German Security Service and Julian Christiansen, the Chief of the Vilnius Abwehr, cooperation between the Germans and the AK was established in the area of Krzyżanowski’s units’ operation. While Krzyzanowski refused to sign an explicit agreement on cooperation, a secret arrangement was made that the AK would “capture” the armaments and provisions left to them by Germans.

However any such arrangements were purely tactical and did not evidenced a type of ideological collaboration as shown by the Vichy regime in France, the Quisling regime in Norway or closer to the region, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. The Poles’ main motivation was to gain intelligence on German morale and preparedness and to acquire some badly needed weapons. There are no known joint Polish-German actions, and the Germans were unsuccessful in their attempt to turn the Poles toward fighting exclusively against Soviet partisans. Such collaboration of local commanders with the Germans was generally atypical and usually occurred due to local circumstances – such incidents were condemned by the AK High Command.

In May 1944 Polish resistance units in the Wilno area were attacked by the Local Lithuanian Detachment under General Povilas Plechavičius. Krzyżanowski attempted to negotiate, but Plechavičius demanded that AK and all Polish partisans retreat from the Wilno region and accept Lithuanian sovereignty over that territory. Krzyżanowski would not agree to such a withdrawal and the fighting escalated, eventually culminating in the Polish victory over the Lithuanian collaborationist forces in the battle of Muravanaya Ashmyanka of May 13-May 14. After that battle Krzyżanowski attempted to resume negotiations but was ignored by the Lithuanian side. The increasing hostilities culminated in June 1944, when pro-NaziLithuanian Security Police forces, which had recently suffered a loss of several members in a skirmish with the AK, massacred 37 Polish civilians in Glinciszki, a village known to support the Polish partisans. Later accusations of widespread massacres made by the Lithuanians against the AK are false and were intended to counteract accusations of widespread German-Lithuanian collaboration and crimes committed by units such as the Lithuanian Secret Police .

Beginning in the spring of 1944 the Polish underground was preparing for the major Operation Tempest, which was designed to cause a large scale uprising behind the German lines to prevent a Soviet takeover of the territory by establishing a local Polish administration before the arrival of the Red Army, as a sign to the entire world that the Polish government in exile commanded significant Polish forces. Operation Tempest would also support of the Soviet Eastern Front offensive. By this time Finland had made a decision to enter the War against Germany and a new and secret Branch of the Finnish Security Service (Suojelupoliisi / Skyddspolisen, abbreviated as SUPO) had been established to support the underground movements in the Baltic States in Poland. Ilmavoimat aircraft began to fly regular supply missions as contacts were established, providing arms, ammunition, radios and training (special teams from the Maavoimat’s Osasto Nyrkki “Fist Force” were inserted to train Polish Home Army members for example. Immediately prior to Operation Tempest commencing, large supply drops had been made and additional Osasto Nyrkki troopers flown in to support and liase with AK units.

After the Poles and Soviets defeated the Germans and captured Wilno on July 17, 1944, Polish officers, including Krzyżanowski, who had been invited to a debriefing with the Soviets, were arrested and briefly imprisoned before being liberated. He would go on to command the 19th Infantry Division (Polish Army) which was formed immediately from Home Army units and equipped from Finnish stockpiles of lend-lease equipment. The 19th Division, the Second Infantry Fusiliers Division and a further newly-formed Division, the 23rd Infantry, would secure the Wilno Region through to the end of WW2. Krzyżanowski health collapsed in 1951 and he died on September 29 of that year from tuberculosis.

Polish Wilno in 1936….

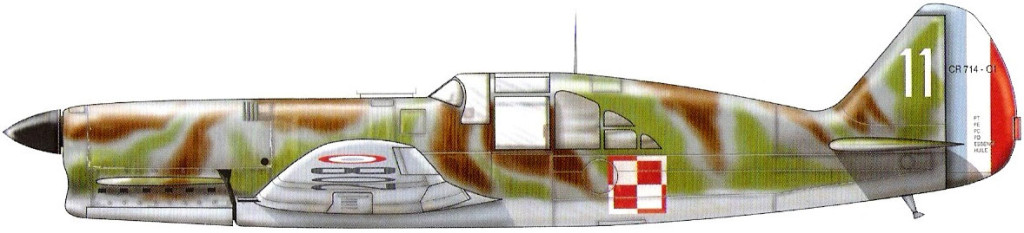

The Caudron-Renault C.714 fighters

The two cargo ships that made up part of the small convoy in addition to artillery pieces and a sizable shipment of artillery shells also carried some forty Caudron-Renault CR714 fighters, in both cases together with Polish pilots and Polish ground crew together with a small team of French engineers to manage the re-assembly of the aircraft on arrival. That these aircraft were actually shipped was again in large part due to the marked emphasis that the French Premier, Paul Reynaud, had placed on visible aid to Finland. Much was made in the French Press of the shipments of aircraft and artillery to Finland – an astute move by Reynaud to at least alleviate some of the pressure from the Right. Even if the move didn’t succeed in bringing them onside, it at least satisfied them to a certain extent. There was no mention of the dispatch of the Polish Division however – it was feared that this might cause problems with the Soviet Union and this was something that caused some trepidation in both Britain and France, even if there were circles in both countries that advocated attacking the USSR as an open ally and source off critical war materials for Germany.

Finland won the propaganda war from the start – and public sympathy in France was strongly on the side of Finland. With the Finnish military successes of early 1940, this added to the pressure on Reynaud to do more than make token gestures.

The C.710 were a series of fighter aircraft developed by Caudron-Renault for the French Armée de l’Air just prior to the start of World War II. The original specification that led to the C.710 series was offered in 1936 in order to quickly raise the number of modern aircraft in French service, by supplying a “light fighter” of wooden construction that could be built rapidly in large numbers without upsetting the production of existing types. The contract resulted in three designs, the Arsenal VG-30, the Bloch MB-700, and the C.710. Prototypes of all three were ordered. The original C.710 model was an angular design developed from an earlier series of air racers. One common feature of the Caudron line was an extremely long nose that set the cockpit far back on the fuselage. The profile was the result of using the 450 hp (336 kW) Renault 12R-01 12-cylinder inline engine, which had a small cross section and was fairly easy to streamline, but very long. The landing gear was fixed and spatted, and the vertical stabilizer was a seemingly World War I-era semicircle instead of a more common trapezoidal or triangular design.

The C.710 prototype first flew on 18 July 1936. Despite its small size, it showed good potential and was able to reach a level speed of 470 km/h (292 mph) during flight testing. Further development continued with the C.711 and C.712 with more powerful engines, while the C.713 which flew on 15 December 1937 introduced retractable landing gear and a more conventional triangular vertical stabilizer. The final evolution of the 710 series was the C.714 Cyclone , a variation on the C.713 which first flew in April 1938, as the C.714.01 prototype. The primary changes were a new wing airfoil profile, a strengthened fuselage, and instead of two cannons the fighter had four 7.5 mm MAC 1934 machine guns in wing gondolas. It was powered by the newer 12R-03 version of the engine, which introduced a new carburettor that could operate in negative g.

The Caudron-Renault C.R. 714 was a single-seat cantilever low-wing monoplane with a wooden structure and retractable main undercarriage. Armament consisted of four 7.5 mm MAC 1934 machine guns in the wing gondolas. They had a maximum speed of 286 mph, a range of 560 miles and were powered by a single Renault 12R 03 inverted V-12 500hp inline piston engine)

The Armée de l’Air had ordered 20 C.714s on 5 November 1938, with options for a further 180. Production started at a Renault factory in the Paris suburbs in 1939. After a series of tests with the first production examples, it became apparent that the design was seriously flawed. Although light and fast, its wooden construction did not permit a more powerful engine to be fitted. The original engine seriously limited its climb rate and manoeuvrability with the result that the initial production order was reduced to 90, as the performance was not considered good enough to warrant further production contracts. After the fall of Poland in 1939, delivered C.714’s were assigned to Polish pilots flying in France (the Polish Warsaw Squadron – the Groupe de Chasse polonais I/145, stationed at the Mions airfield). After just 23 sorties, an adverse opinion of the fighter was confirmed by front-line pilots who expressed concerns that it was seriously under-powered and was no match for contemporary German fighters.

The Caudron fighter was also used by the Polish training squadron based in Bron near Lyon. Although the pilots managed to disperse several bombing raids, they did not score any kills although they also did not lose any machines. French Minister of War Guy la Chambre ordered all C714s to be withdrawn from active service. However, since the French authorities had no other aircraft to offer, the Polish pilots ignored the order and continued to fly the Caudrons. Despite flying a fighter hopelessly outdated compared to the Messerschmitt Me 109E, the Polish pilots scored 12 confirmed and three unconfirmed victories in three battles, losing nine Caudrons in the air and nine more on the ground. Interestingly, among the planes shot down were four Dornier Do 17 bombers, but also three Messerschmitt Bf 109 and five Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters.

In total, 98 C714’s were delivered, with 18 lost in combat. The French government decided to divert the remaining eighty to Finland within days of Reynaud taking office – a decision made easier by the decision that these aircraft should be withdrawn from combat. Reynaud was firm on making a visible commitment and in this way, the commitment could be made very publicly – eighty aircraft was a sizable number indeed – and at the same time the Armée de l’Air could rid itself of aircraft that would otherwise just have been scrapped. They could also get rid of some of those annoying Poles, thus killing three birds with one stone. It was a very French solution. Forty of the aircraft were crated for shipment and moved to Le Havre together with the Polish personnel, from where they were loaded and shipped almost immediately.