1937 was a relatively straightforward year for VL (the State Aircraft Factory) – delivery of the Fokker D.XXI fighters, Bristol Blenheim bombers and Viima trainers continued, monopolising all of VL’s construction capacity. However, for the 1937 Ilmavoimat / Merivoimat Air Arm Procurement Team it was a rather more challenging year. Budgetary provisions for the Ilmavoimat in 1937 had increased and Somersalo and the Fighter advocates were pushing strongly for a front-line fighter which would be on a par with the more modern fighters that were even now beginning to supersede in capabilities the Fokker D.XXI in other european air forces. In addition, the Merivoimat had a (what was for them) large budget allocation for aircraft for the Merivoimat Air Arm (the 1937 Merivoimat budget included provision for one fighter squadron and one dive-bomber squadron as well as a limited number of transport aircraft).

An additional and important factor was that in early 1937, as mentioned in an earlier Post, the Finnish Finance Minister, Risto Ryti, had scored a major coup in negotiating a thirty million dollar loan on very favorable terms from the United States Government for the purchase of military equipment from US suppliers. A good half of this loan was allocated to the acquisition of artillery, munitions and the like for the Armiejan, twenty five percent to the purchase of industrial machinery while the remainder was allocated to the Ilmavoimat for the purchase of more modern aircraft, primarily fighters. In the same period (early 1937), the Finance Minister had also negotiated a substantial loan under similar favorable conditions from the French government for the purchase of French weapons, armored vehicles, aircraft and munitions. While there were accusations from the left that the country was being bankrupted and mortgaged into ruin to finance the military, this was an extreme left view that was largely ignored by the bulk of the electorate, many of whom were committed members of either the Civil Guard or the Active Reserves – which now included a sizable proportion of SDP members.

All that aside however, the first three orders placed in 1937 were actually for British and Italian aircraft.

The first of these orders was for an Advanced Training Aircraft. As mentioned, in 1936, with the rapid expansion of the Ilmavoimat well underway and with a rapidly increasing demand for training aircraft that was beginning to exceed availability, it had been decided that more Advanced Trainers were required and the VL Pyry prototype had been commissioned. However, this was not expected to be completed and thoroughly tested until 1938. At the same time it was also recognized that the State Aircraft Factory was already heavily committed to construction to meet existing orders and, while expanding capacity rapidly, could not deliver additional Advanced Trainers quickly and in the numbers needed. A decision was therefore made in the first quarter of 1937 to purchase Advanced Trainers from abroad in addition to the Pyry order placed with VL.

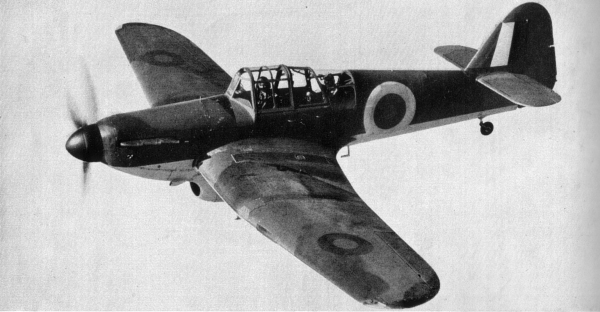

Miles M.9 Kestrel Advanced Trainer – 40 Ordered 1937, further 20 ordered as a Glider Tug version later in 1937

In looking for a good low-wing monoplane trainer, the Ilmavoimat Procurement Team had sounded out their contacts in various countries. Within the UK, this led them to examine the Miles Magister, which was designed specifically as a trainer for the RAF, serving as an ideal introduction to the Spitfire and Hurricane for new pilots. The Magister first flew in March 1937 and the RAF ordered it in large numbers with production commencing in October 1937. At the same time, F.G, Miles, the designer, had been working on the design for the Miles Kestrel advanced trainer and at the time the Ilmavoimat Team contacted him (in July 1937), the prototype was about to fly – indeed, it was demonstrated at the Hendon Airshow (in the UK) in July 1937.

The M.9 Kestrel, powered by the 745 hp (555 kW) Rolls-Royce Kestrel XVI V-12 engine, could reach 295 mph (475 km/h), had a range of 393 miles, a crew of two (Instructor and Student) and had a service ceiling of 28,000 feet. In trainer form, the Kestrel was equipped to carry eight practice bombs, plus one .303in Vickers machine gun mounted in the front fuselage. It was also modified for use as a Glider Tug and the Ilmavoimat aircraft were designed and built with six wing-mounted .303 in Browning machine guns to enable use as an emergency fighter. Kestrels were built by Phillips and Powis Aircraft Limited at Woodley, Berkshire (UK).

After evaluating a number of Advanced Trainer aircraft types from early to mid 1937, the Ilmavoimat knew a winner when they saw one and after a through evaluation and test flight program of their own, a decision was made by the Ilmavoimat to purchase the Miles M9 Kestrel as an Advanced Trainer. The Ilmavoimat placed an order for 40 of the Miles Kestrel Trainers in late 1937. These were built by Phillips and Powis Aircraft Limited at Woodley, Berkshire (UK) and delivered to Finland from early to mid-1938. The Ilmavoimat had had the design modified to include six wing-mounted .303 in Browning machine guns in all aircraft so as to enable use as an emergency fighter.

Also in early 1937, the newly formed Finnish Special Operations Command had begun experimenting with gliders and had purchased a small number of the German DFS230 Gliders from the Deutsche Forschungsanstalt für Segelflug for trials. By mid-1937 it had been decided to design and build gliders for the Special Operations units and the newly forming Parajaeger (Paratroop) Division, and with additional DFS230’s being built for training, tugs were needed. An additional order was placed towards the end of 1937 for a further 20 Miles Kestrel’ to be delivered specifically for the glider-towing role, with the bottom of the rudder cut away to allow fitting of a towing hook. These 20 aircraft were also delivered in mid-1938 and were used exclusively by the Glider Training School. The forty Advanced Trainers were later modified to allow them to also be used as Glider Tugs.

The Kestrel’s maximum speed of 295 mph was actually higher than the Fokker D.XXI’s 280 mph and its six machineguns compared favorably with the four mounted in the Fokker. In the event, all forty Kestrel Trainer’s were at various times thrown into the Winter War as fighters, primarily used in the air defence of Turku, Vaasa, Tampere and Helsinki, and were flown by Instructors and students near graduation from the Fighter Pilot Training School, achieving some significant successes in attacks on Soviet bomber formations in the early days of the war. The Kestrel’s performance was quite remarkable, only 15 mph less than the concurrent version of the Hurricane, making it one of the fastest and most maneuverable trainers of its day. It would serve within the Ilmavoimat for the duration of WW2 and well into the 1950’s before it was retired.

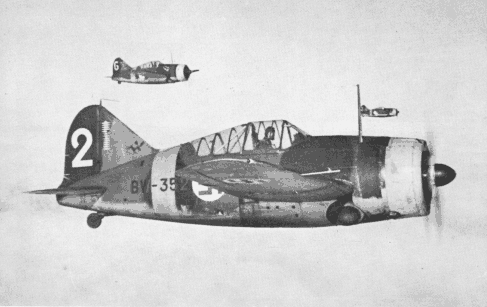

Curtiss Hawk Model 75 Fighter – 40 ordered in mid 1937

With substantial funding secured from both the United States in the form of a large loan in early 1937, the Finnish Air Force’s upgrading continued to move ahead at a consistent pace. As previously mentioned, by 1937 the Ilmavoimat was being allocated the financing to procure an additional 2 to 3 squadrons of imported fighter aircraft each year, in addition to whatever could be locally constructed. The securing of the huge US loan in 1937 made it possible to purchase aircraft from the United States, which was, as of the late thirties, the only western country capable of large scale aircraft manufacturing for export (Britain and France were both concentrating on rearmament of their own air forces with consequent impact on exports).

Now that it was possible to purchase more modern aircraft from the United States, albeit at a higher cost, the Ilmavoimat proceeded to do just that. The first truly modern fighter the Finns purchased was a direct result of this loan funding being made available. The Ilmavoimat Procurement Team had been well aware of the Curtiss Hawks, and had also been informed that the aircraft was a private venture by the company and thus it turned out to be far easier to contract for the numbers of aircraft that they wanted as they were not then being produced for the US Armed Forces, which was itself experiencing a massive buildup in strength. For the Finns, one of the joys of buying from the United States was the sheer scale possible for industrial production of aircraft. Having sourced limited numbers of fighter and bomber aircraft from the British, Italians, Germans and Dutch in the past, and having struggled to acquire more than a few aircraft at a time over an extended period, the sheer scale of what was possible with such financing available overwhelmed them. The Curtiss Hawks were acquired for approximately $55,000 each (approximately the same as for the Hawker Hurricane) with an additional amount for spare parts and, having had the prototype built in 1934, were able to be rapidly manufactured and delivered to the Ilmavoimat. An order for Curtiss Hawks was placed in mid-1937.

However, the spanner in the works for this order was a combination of a French order for the Curtiss Hawk and opposition from the USAAC. France in 1937, as a result of industry nationalisation and the recent introduction of the forty hour working week, suffered from production bottlenecks due mainly to the lack of mass production techniques and was having great difficulty in meeting its own aircraft production needs. The only realistic answer was foreign purchase, and with Britain also rearming at full speed, the United States was the only source for combat aircraft supply. Even before the Hawk entered production, the French Air Force had entered negotiations with Curtiss for delivery of 300 aircraft.

The negotiating process ended up being very drawn-out because the cost of the Curtiss fighters was double that of the French Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 and Bloch MB.150, and the delivery schedule was deemed too slow. Since the USAAC was unhappy with the rate of domestic deliveries and believed that export aircraft would slow things down even more, it actively opposed the sale to the French, which incidentally also impacted the Ilmavoimat order. Eventually, it took direct intervention from U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt to give the French test pilot Michel Detroyat a chance to fly the aircraft. Detroyat’s enthusiasm, problems with the Bloch MB.150, and the pressure of continuing German rearmament finally forced France to purchase 100 aircraft and 173 engines.

The first Hawk 75A-1 arrived in France in December 1938 and they began entering service in March 1939. After the first few examples, aircraft were delivered in pieces and assembled in France. Officially designated Curtiss H75-C1 (the “Hawk” name was not used in France), the aircraft were powered by Pratt & Whitney R-1830-SC-G engines with 900 hp (671 kW) and had metric, translated instruments, a seat for French dorsal parachutes, a French-style throttle which operated in reverse from U.S. and British aircraft (e.g. full throttle was to the rear rather than to the front) and armament of four 7.5 mm FN-Browning machine guns. The aircraft evolved through several modifications, the most significant being the installation of the Wright R-1820 Cyclone engine. This variant, designated as Curtiss H751-C1, saw little operational use due to its late delivery and reliability problems with the new engine. A total of 416 H75’s were delivered to France before the German occupation.

However, in the midst of all this the Finns had managed to have their order approved (after all, what use was a thirty million dollar loan for defence-related purchases if it couldn’t be used) and the forty Hawks ordered by the Ilmavoimat were the first off the production line. Subsequently, the shipment of forty Hawk 75A-1’s arrived in Turku in December 1938, and began entering service in March 1939. Delivery was completed with a second shipment of spare parts received in June 1939. The Curtiss Hawk Model 75A-1 made a welcome addition to the Ilmavoimat’s strength.

A contemporary of the Hawker Hurricane and Messerschmitt Bf 109, the Curtiss Hawk Model 75 was one of the first fighters of the new generation – sleek monoplanes with extensive use of metal in construction and powerful piston engines. The first prototype constructed in 1934 featured all-metal construction with fabric-covered control surfaces, a Wright XR-1670-5 radial engine developing 900 hp, and an armament of one 0.30-cal. and one 0.50-cal. machine guns firing through the propeller arc. Also typical of the time was the total absence of armor or self-sealing fuel tanks. The distinctive landing gear which rotated 90 degrees to fold the main wheels flat into the thin trailing portion of the wing was actually a Boeing-patented design for which Curtiss had to pay royalties.

The Hawk prototype had first flown in May 1935, reaching 281 mph (452 km/h) at 10,000 ft (3,050 m) during early test flights. The initial engine (the unreliable Wright XR-1670-5 radial engine) was replaced with a Pratt & Whitney R-1830-13 Twin Wasp engine producing 900 hp (671 kW) and the fuselage was reworked, adding the distinctive scalloped rear windows to improve rear visibility. Interestingly, a comparison of a Hawk with a Supermarine Spitfire Mk I revealed that the Hawk had several advantages over the early variant of the iconic British fighter. The Hawk was found to have lighter controls than the Spitfire at speeds over 300 mph (480 km/h), especially in diving attacks, and was easier to maneuver in a dogfight thanks to the less-sensitive elevator and better all-around visibility. The Hawk was also easier to control on takeoff and landing. Not surprisingly, the Spitfire’s superior acceleration and top speed ultimately gave it the advantage of being able to engage and leave combat at will, but the Hawk turned out to be an excellent fighter that proved itself effective in combat.

The Royal Air Force also displayed interest in the aircraft, tested the Hawk H-75A’s and found them to be generally inferior to both the Hurricane and Spitfire in both speed and armament. Comparison of a borrowed French Hawk 75A-2 with a Supermarine Spitfire Mk I revealed however that the Hawk did have several advantages over the early variant of the iconic British fighter. The Hawk was found to have lighter controls than the Spitfire at speeds over 300 mph (480 km/h), especially in diving attacks, and was easier to maneuver in a dogfight (thanks to the less sensitive elevator) and better all-around visibility – the Hurricane, Spitfire and the Bf-109 all tended to exhibit heavy control forces at these speeds. The Hawk was also easier to control on takeoff and landing and was found to be more maneuverable than the Spitfire at any speed, athough the Spitfire had a better sustained turn rate. The Hawk French pilots had also commented on the ease and rapidity of maneuvers. Not surprisingly, the Spitfire’s superior acceleration and top speed ultimately gave it the advantage of being able to engage and leave combat at will. Although Britain decided not to purchase the aircraft, they soon came in possession of 229 Hawks comprised of diverted shipments to occupied France and aircraft flown by escaping French pilots.

The Curtiss Hawk 75-A CU-558 in this picture achieved 13 victories in WW2. In Ilmavoimat service, the Hawk was well-liked, affectionately called Sussu (“Sweetheart”). The Ilmavoimat enjoyed success with the type, credited with 190 1/3 kills by 58 pilots over the course of the Winter War, for the loss of 15 of their own. Finnish ace Kyösti Karhila scored 13 1/4 of his 32 victories in the Hawk, while the top Hawk ace K. Tervo scored 15 3/4 victories. Sourced from an original painting by artist Sture Gripenberg. A limited edition of 200 copies has been printed. The proofs are numbered and they are signed by Finnish Air Force ace Kyösti Karhila and the artist.

The Ilmavoimat Hawks as delivered were armed with one 12.7 mm Colt machine gun in the fuselage and four 7.7 mm Browning machine guns on each wing. The Finnish Hawks were also equipped with Revi 3D or C/12D gunsight. As delivered they had a top speed of 322 mph (slightly slower than the Hurricane), a ceiling of 32,340 feet and a range of 650 miles. While sufficient during the Winter War, the increasing speeds and armor of aircraft soon showed this armament was not powerful enough. The installation of heavier armament did not cause changes to the very good flying characteristics of the fighter but the armament was much more powerful against German planes in the later stages of WW2. The Finnish Hawks were also equipped with Revi 3D or C/12D gunsight. Surviving Finnish aircraft remained in service with the FAF aviation units HLeLv 13, HLeLv 11 and LeSK until 1946.

In combat against the Soviet Air Force, the Hawk proved to be an excellent dogfighter, much more agile than the Soviet fighter aircraft and easily able to outturn Soviet aircraft in most manoeuvres. It also had a superior diving speed, which allowed the experienced Finnish pilots to break off an engagement at will provided that there was enough altitude. In terms of general reliability, the Curtiss fighter was strongly built, with a robust structure that could withstand a lot of combat damage and rough field handling. The aircraft was designed for ease of maintenance with excellent access to important components and the Twin-Wasp engines proved to be highly reliable. The armament was a weak point, with the 7.7mm machine guns proving (as they did in many other airforces) to be ineffective at longer range. However, the Ilmavoimat tactic of closing to practically point blank range wherever possible tended to reduce the impact of this weakness in practice.

Ilmavoimat Douglas DC-3 Transport Aircraft – ordered in early 1937

With the formation of the Finnish Army’s Parajaeger Division in 1936, the Military Command started in 1937 to look at suitable aircraft for carrying paratroops as well as for towing the military gliders that were being assessed and tested from Germany or that were on the drawing board as part of the Special Operations Command programs. The results of the earlier transport aircraft evaluation were looked at but the major influencing factor this time around was the substantial loan made available by the US Government in early 1937 – tied to a proviso that the financing was available for purchases from US manufacturers only – and it was this loan which financed the purchase of the aircraft.

Twenty Douglas DC3’s were ordered in the first quarter of 1937. They were built at the Douglas manufacturing plant at Santa Monica, California, Long Beach, California and shipped to Finland, arriving in Turku in late 1937, where they were freighted to the State Aircraft Factory for assembly and test flights, entering service with Aero Oy in the first quarter of 1938 and forming a Transport Squadron of the Air Force Reserve. The DC3’s were utilised as passenger aircraft by Aero Oy. In war, they were to be mobilised by the Ilmavoimat and would be allocated to a Reserve Squadron whose personnel were all Aero Oy aircrew and groundcrew.

Sotka” The first DC-3 of Aero Oy (1938). The depicted OH-LCA was destroyed in an accident in November 1963. The Print is by Sture Gripenberg, taken from a watercolour (http://personal.eunet.fi/pp/gdes/ENG/21.htm). The proofs are signed by captains Seppo Saario, Mauri Maunola and Börje Hielm, radio operator Kosti Uotila and stewardess Kirsti Müller.

The Douglas DC-3 was an American fixed-wing, propeller-driven aircraft whose speed and range revolutionized air transport starting in the mid-1930s. The DC-3 was engineered by a team led by chief engineer Arthur E. Raymond, and first flew on 17 December 1935. The aircraft was the result of a marathon phone call from American Airlines CEO Cyrus Smith to Donald Douglas requesting the design of an improved successor to the DC-2 (of which the Ilmavoimat already had a small number purchased in 1935). The DC3 had gone into production in 1936 and both civilian and military versions were available. The majority of military DC3’s used the Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial which offered better high-altitude and single engine performance. The aircraft quickly developed a reputation for ruggedness – enshrined in the lighthearted description of the DC-3 as “a collection of parts flying in loose formation.” Its ability to take off and land on grass or dirt runways also mades it popular in countries such as Finland where the runway was not always a paved surface.

OH-LCA “Sotka” was the first of a series of DC3 aircraft delivered to Finland prior to WW2. They flew as passenger aircraft prior to the Winter War, were mobilized by the Ilmavoimat for the duration of WW2 and post-war, after being refurbished, the survivors went back into passenger service with Aero Oy (which was be then renamed Finnish Air Lines). Ten of the DC-3s that survived the war were in operation from 1946 to 1965.

The DC3 had a maximum speed of 237 mph, a range of 1,025 miles, a service ceiling of 24,000 feet and, with a Crew of 2, could carry 20 fully-loaded paratroops. They were powered by Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engines of 1100hp each and could be fitted with skis or floats as well as wheels. They were taken too immediately by their pilots and served through the war years as the primary transport workhorse of the Ilmavoimat. The aircraft were allocated to LLv.18, (Flying Squadron 18) – 6th Flight Regiment (Air Transport).

Merivoimat Douglas DC-3 Transport Aircraft – 10 ordered in 1937

The Merivoimat was also intent on purchasing a number of transport aircraft for use in a supporting role for the Rannikkojääkärit. With the Ilmavoimat’s decision to purchase DC3’s, the logical decision for the Merivoimat was to follow suite, and this they did. The Merivoimat’s DC3’s were delivered together with the Ilmavoimat order in December 1937 and in service in early 1938. Unlike the Ilmavoimat, the Merivoimat retained their DC3’s and used them over 1938 and 1939 to develop tactical doctrine of both providing transport support for Rannikkojääkärit operations and for the evolving tactic of parachuting Rannikkojääkärit troops into operations.

De Havilland Wihuri (“Mosquito”) Medium Bomber – ordered mid-1937

A rather more innovative and also rather risky (in that it was unproven) acquisition by the Ilmavoimat was the purchase of a manufacturing license by the State Aircraft Factory for the De Havilland “Wihuri” in mid-1937 (built under license in Finland).

While the De Havilland Mosquito was first proposed to the UK’s Air Ministry in late 1938 and the first prototype flew in November 1940, 10 months after the actual go-ahead, it could have come about much sooner. Throughout the 1930s, de Havilland had established a reputation in developing innovative high-speed aircraft such as the DH.88 Comet mailplane and DH.91 Albatross airliner that had already successfully employed the composite wood construction that the Mosquito would use. There two earlier aircraft were instrumental in the emergence of the Mosquito. The de Havilland DH.88 Comet was a twin-engined British aircraft that won the 1934 MacRobertson Air Race. It set many aviation records during the race and afterwards as a pioneer mail plane. The airframe consisted of a wooden skeleton clad with spruce plywood, with a final fabric covering on the wings. A long streamlined nose held the main fuel tanks, with the low set central two-seat cockpit forming an unbroken line to the tail. The engines were essentially the standard Gipsy Six used on the Express and Dragon Rapide passenger planes, tuned for best performance with a higher compression ratio. The propellers were two-position variable pitch, manually set to fine before takeoff and changed automatically to coarse by a pressure sensor. The main undercarriage retracted upwards and backwards into the engine nacelles. The DH.88 could maintain altitude up to 4,000 ft (1,200 m) on one engine.

In 1935, de Havilland had already suggested a high-speed bomber version of the DH.88 to the RAF, but the suggestion was rejected (OTL, De Havilland later developed the de Havilland Mosquito along similar lines as the DH.88 for the high-speed bomber role). As it turned out, experience with the DH.88 would be put to use in designing one of the war’s finest aircraft—the de Havilland Wihuri (“Mosquito”). A second aircraft developed along the same lines was the de Havilland DH.91 Albatross. This was a four-engine British transport aircraft developed in the 1930s. A total of seven aircraft were built in 1938-1939. The DH.91 was designed in 1936 by A. E. Hagg to Air Ministry specification 36/35 for a trans-Atlantic mail plane. The aircraft was remarkable for the ply-balsa-ply sandwich construction of its fuselage which was later made famous in the de Havilland Mosquito bomber. The first Albatross flew on May 20, 1937. Production was limited and the type was retired in 1943.

In June 1937, one of the small team of Ilmavoimat officers based in London and managing the procurement program from British aircraft manufacturers was invited to view the new De Havilland Albatross. Having already seen the De Havilland Comet, this officer was also aware of De Havilland’s 1935 proposal to the British Air Ministry for a high speed all-wooden bomber. Interested by the suitability for Finland of the Alabtross’s construction techniques and material composition, aware of VL’s research program with regard to the earlier Haukka II Fighter which had led to innovations in the Finnish timber industry and putting two plus two together, this officer made further inquiries about the possibility of designing and building such a high-speed bomber for the Ilmavoimat, along with licensing production by Finland.

He was impressed enough following initial discussions with De Havilland that he had recommended an urgent followup. In Helsinki, his immediate superior in the procurement program was convinced enough that he recommended a team visit De Havilland immediately. Somersalo (and Mannerheim himself) had become involved as it became obvious that the all-wood aircraft was uniquely suited to Finland’s resources and manufacturing capabilities and, together they joined the team that visited the De Havilland offices for initial discussions. At the same time, the Ilmavoimat was negotiating orders for the Miles Kestrel Advanced Trainers and Glider Tugs. Marshal Mannerheim and Somersalo, the head of the Ilmavoimat, used the opportunity to meet personally with Geoffrey de Havilland Sr. and discuss the possibility of contracting with de Havilland for the design and construction of a high speed medium bomber based on discussions the Ilmavoimat team had already had with De Havilland.

The interest was mutual, with De Havilland demonstrating the Comet and the Albatross and reviewing the construction techniques for the Albatross together with the conceptual work De Havilland had already done on a fast medium bomber. The end result of the intensive week-long series of meetings was a contract (signed in early July 1937) with De Havilland for the design and development of a prototype in an accelerated timeframe. A number of qualifiers were added – primarily the use of Bristol Blenheim cockpit instruments and the Blenheim undercarriage and the use of Merlin engines, the construction of which Finland had just signed a license for. Subject to acceptance of the prototype, the Ilmavoimat signed a statement of intent for the construction of forty aircraft and the purchase of an unlimited manufacturing license together with the immediate assistance of a De Havilland Team in setting up VL production facilities and starting construction in Finland. The cost of the prototype would be shared equally between both parties, but with Finland supplying the engines.

A joint team from the Ilmavoimat and from VL, including VL’s lead designer Arvo Ylinen, were on the way within days of the contract being signed, and worked closely with De Havilland over an intensive four month design and prototype construction period. While the Finnish aircraft started off as an adaptation of the Albatross, the Ilmavoimat was from the first, looking for a fast lightweight tactical medium bomber and fighter-bomber capable of also filling a ground-attack role rather than a strategic heavy bomber. The designers worked to remove everything that was unneeded in order to lower the weight. The initial design had started off as an adaptation of the Albatross, armed with three gun turrets and a six-man crew, and powered by two Rolls-Royce Merlin engines. The designers started removing everything that was unneeded in order to lower the weight. As each of the gun turrets was eliminated, the performance of the aircraft continued to improve, until they realised that, by removing all of them, the aircraft would be so fast it might not need guns at all. What emerged was the concept that the Ilmavoimat team had been grasping at but had not quite visualized, a small twin-engined, two crew aircraft so fast that nothing in the sky could catch it. It could carry 1,000 lb (454 kg) of bombs for 1,500 miles (2,414 km) at a speed of almost 400 mph (644 km/h), which was almost twice that of contemporary British bombers. And at the same time, three basic design variations had been mapped out – a fighter-bomber, a medium bomber and a reconnaissance version.

The original estimates at the time of the initial meetings had been that as the bomber prototype had twice the surface area and over twice the weight of the Spitfire, but also with twice its power, it would end up being 20 mph (32 km/h) faster than the Spitfire. By December 1937 the prototype had been completed. The bulk of the Wihuri, as it was now being called, was made of custom plywood – and from the start, the Finnish wood industry was closely involved. The fuselage was a frameless monocoque shell built by forming up plywood made of 3/8″ sheets of Ecuadorean balsawood sandwiched between sheets of Finnish birch. These were formed inside large concrete moulds, each holding one half of the fuselage, split vertically. While the casein-based glue in the plywood dried, carpenters cut a sawtooth joint into their edges while other workers installed the controls and cabling on the inside wall. When the glue was completely dried, the two halves were glued and screwed together. A covering of doped Madapolam (a fine plain woven cotton) fabric completed the unit.

The wings were similar but used different materials and techniques. The wing was built as a single unit, not two sides, based on two birch plywood boxes as spars fore and aft. Plywood ribs and stringers were glued and screwed to form the basic wing shape. The skinning was also birch plywood, one layer thick on the bottom and doubled up on the top. Between the two top layers was another layer of fir stringers. Building up the structure used an enormous number of brass screws, 30,000 per wing. The wing was completed with wooden flaps and aluminium ailerons. When both parts were complete the fuselage was lowered onto the wing, and once again glued and screwed together. The remainder consisted of wooden horizontal and vertical tail surfaces, with aluminium control surfaces. Engine mounts of welded steel tube were added, along with simple landing gear oleos filled with rubber blocks. Wood was used to carry only in-plane loads, with metal fittings used for all triaxially loaded components such as landing gear, engine mounts, control surface mounting brackets, and the wing-to-fuselage junction. The total weight of metal castings and forgings used in the aircraft was only 280 lbs. The glue used was initially casein-based.

In testing of the first prototype over December 1937-January 1938, the prototype surpassed all estimates, easily besting the Spitfire in testing with a top speed of 392 mph (631 km/h) at 22,000 ft (6,700 m) altitude, compared to a top speed of 360 mph (579 km/h) at 19,500 ft (6,000 m) for the Spitfire. Construction of a prototype Wihuri fighter-bomber version was then carried out and in May 1938, Geoffrey De Havilland personally flew this off a 450 foot field. The first reconnaissance prototype followed on 10 June 1938. During testing of the bomber version, it was found that the Wihuri day bomber prototype had the power and internal capacity to carry not just the 1,000 lbs of bombs originally specified, but four times that figure. In order to better support the higher loads the aircraft was capable of, the wingspan was increased from 52 ft 6in (16.0 m) to 54 ft 2in (16.5 m). It was also fitted with a larger tailplane, improved exhaust system, and lengthened nacelles that improved stability.

Following the successful trials of the prototype day bomber, the prodution order for forty aircraft was confirmed and construction was started by De Havilland. The forty Wihuris were built as fast bombers with construction starting in March 1938, and all forty were completed and handed over by December 1938. They could carry a 4000 lb bomb load and the design team had worked in external drop tanks which extended the range to 2500 miles. The fighter-bomber version completed it’s trials in June 1938, by which time the Ilmavoimat had confirmed an order for twenty of this type – and De Havilland started construction of the remaining twenty aircraft of the order as the fighter-bomber variant in November 1938. The fighter-bomber version had a strengthened wing for external loads and along with its standard fighter armament of four 20 mm Hispano-Suiza HS-9 cannon mounted in the fuselage and a further four 7.7mm Brownings mounted in the nose, it could carry two 250 lb bombs in the rear of the bomb bay and two 250 lb bombs under the wings. These aircraft were delivered in April 1939. An order for a further twenty had been placed in October 1938 as it was realized that VL (the State Aircraft Factory) would not be able to commence production until at least the end of the second quarter of 1939. These additional twenty fighter-bombers were delivered in June 1939. An order for a further twenty had been placed by then but this was canceled and the order was taken over by the RAF. However, the British did offer the Finns other aircraft in compensation – something that will be covered when we review 1939. Attempts to order more Wihuri’s from de Havilland as the Winter War broke out were declined.

Within weeks of the fighter-bomber trials having been completed, a team from De Havilland was on their way to Helsinki to assist the State Aircraft Factory to start up production. Startup was slower than planned. Subcontractors had to be contracted and trained, local materials sourced, production facilities built, workers hired and trained. The De Havilland-VL Team worked around the clock, twelve hour days, seven day weeks. Fuselage shells were made by two local furniture companies. The specialized wood veneer used in the construction of the Wihuri was made by Tampere Wood Veneers, who had teams of dexterous young women ironing the (unusually thin) strong wood veneer product before shipping to the assembly plant. Wing spars and many of the other parts, including flaps, flap shrouds, fins, leading edge assemblies and bomb doors were also produced locally by the established furniture-manufacturing industry. The Merlin engines were produced by the State Aircraft Engine Factory, while VL supplied Blenheim instruments and undercarriages from the Blenheim production line.The first Finnish-built prototype flew almost a year later, in June 1939.

A picture from the Finnish Central Air Museum warehouse in 1991 – the crates contain blue prints and original drawings of the de Havilland Wihuri that were used by VL in the manufacture of the aircraft

By October 1939, forty bomber versions and forty fighter-bomber had been delivered from De Havilland and were in service. And by October 1939, VL production had actually started, with two aircraft a month rolling of the VL production line. With Soviet threats becoming ever more blatant, VL made every effort to ramp up production but the Winter War broke out before this could be achieved. However, by the end of November 1939 the first four Finnish-built Wihuri’s (all fighter-bomber variants) had been completed and were in service, bringing the total number available to 84 – and an increase in production to four a month would take place from December 1939 on.

The performance of the VL Wihuri was a source of wonder to the Finnish pilots assigned to the aircraft. At 415 mph, the sheer speed of the plane and its ability to outfly anything and everything else the Finn’s had, even the fighters, was astounding. And the operational ceiling was outstanding. With no bombload, she could fly even higher and the Ilmavoimat put this capability to good use with reconnaisance flights over the Soviet Union taking place again and again in late 1939. Able to fly at over 40,000 feet, it let them watch everything the Soviet’s were up to with little or no suspicion they were being watched.

Stepping back a little, in August 1939 VL began to experiment with mounting a 37mm Anti-tank gun in the aircraft, intending to use this as a counter-measure to the overwhelming numbers of Soviet tanks should a war occur, as was seeming more and more likely. With the assistance of De Havilland, an auto-loader was designed and built by a British company, Molins, to allow both semi- or fully-automatic fire with the nose-mounted gun. Ground trials of the auto-loader proved successful, as did experiments in how best to mount the gun within the Wihuri. The November 1939 production run of two aircraft were fitted with the 37mm gun in the nose for air trials, along with two .303 in (7.7 mm) sighting machine guns. With the outbreak of the Winter War on the 30th of November 1939, the trials were “live” – and highly successful. But while highly effective, the 37mm gun did require a steady and vulnerable approach-run to aim and fire the gun and there was a weight penalty. Given the overwhelming numbers of tanks the Red Army was throwing at the Armeijan, it was decided however that the benefits of an airborne anti-tank gun were well worth it and that the next series of Wihuri’s off the VL production line would be this version.

With 4 Wihuri’s a month rolling off the production line, 20 of these aircraft had been delivered by the time of the May 1940 “Spring Offensive” that recaptured the Karelian Isthmus from the Red Army. Overall, the Wihuri was an aircraft that was to prove of incalculable value to the Finns in the Winter War, and one which was a complete surprise both to the Soviet Air Force and to the Red Army. And it could also be effective on aircraft as well as ground targets. The effect of the new weapon on aircraft was demonstrated on 10 March 1940 when one 37mm-equipped Wihuri attacked 10 Soviet SB2 bombers. Three of the SB2’s were shot down. One SB2 was destroyed with four shells, one of which tore an entire engine off the SB2.

However, at the time the Wihuri Project was started, there were no guarantees of its success and a number of other, smaller, aircraft orders were also initiated in 1937. We will look at these next.

Earlier in this Chapter, it was mentioned that there were two British aircraft and one Italian aircraft ordered almost immediately at the start of 1937. But I jumped to orders placed later in 1937…… So, to rectify the omission, here is one of those immediate orders…..

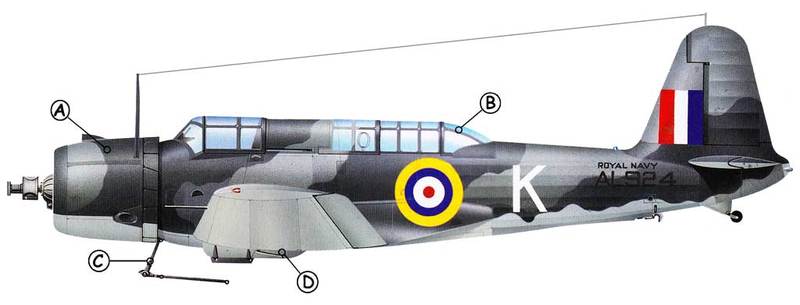

The Avro Anson Multi-role Aircraft – ordered January 1937

The Avro Anson was a British twin-engine, multi-role aircraft that served with the Royal Air Force, Fleet Air Arm and numerous other air forces during the Second World War and afterwards. The Anson was derived from the commercial six-seat Avro 652 and the militarised version, which first flew on 24 March 1935, was built to Air Ministry Specification 18/35.

It was the first RAF monoplane with a retractable undercarriage. A distinctive feature of the Anson was its landing gear retraction mechanism which required no less than 140 turns of the hand crank by the pilot. To forgo this laborious process, Ansons often flew with the landing gear extended at the expense of 30 mph (50 km/h) of cruise speed. The Anson required a crew of 3-4, was powered by 2× Armstrong Siddeley Cheetah IX radial engines, 350 hp (260 kW) each, had a masimum speed of 188mph, a range of 790 miles, a service ceiling of 19,000 feet and was armed with 1× .303 in (7.70 mm) machine gun in the front fuselage and 1× .303 in Vickers K machine gun in the dorsal turret. The Anson could also carry one 360 lb (160 kg) bomb or depth charge.

The Eesti Õhuvägi’s (Estonian Air Force) sole Avro Anson, acquired for evaluation. This aircraft escaped from Estonia when the Soviets attacked the country and made it to Finland, where it served with the Ilmavoimat until the liberation of Estonia.

In January 1937, the ilmavoimat ordered 10 Avro Anson I aircraft directly from the factory. The first was delivered in Manchester, U.K. on 25 April 1937 and flown to Finland via the route Croydon – Amsterdam – Malmö – Turku, where the aircraft arrived on 1 May. Delivery of all aircraft orded was completed by December 1937. It was originally designed for maritime reconnaissance but was soon rendered obsolete. However it was rescued from obscurity by its suitability as a multi-engine air crew trainer, and it was primarily for this purpose, with a secondary role as a light transport that the Ilmavoimat purchased the aircraft. All Anson’s purchased were attached to the Pilot Training School. The Ilmavoimat also at times used the Anson in operational roles such as coastal patrols and air/sea rescue. The aircraft’s primary role, however, was to train pilots for flying the Ilmavoimat’s multi-engine bombers and transports such as the Blenheim, SM-73 and DC3. The Anson was also used to train the other members of a bomber’s air crew, such as navigators, wireless operators, bomb aimers and air gunners.

The Anson was a maneoueverable aircraft – in January 1940, a training flight of three Ansons over the Gulf of Finland was attacked by nine Soviet Air Force fighters. Remarkably, the Ansons downed two Soviet aircraft “and damaging a third before the ‘dogfight’ ended”, without losing any of their own. Incidentally the Eesti Õhuvägi (Estonian Air Force) also acquired a single Avro Anson.

Merivoimat Air Arm Fighter – the Brewster Buffalo, 20 ordered mid-December 1937, a further 20 ordered in April 1938

The 1937 budget included provision for the purchase of fighter aircraft to fit out one squadron for the Merivoimat Air Arm. The stated objectives for the Air Arm Fighters were to provide fighter cover for Merivoimat ships operating in the Baltic and to provide fighter cover for Rannikkojääkärit (Marine) operations, primarily along the Gulf of Finland littoral. To this end, a fighter with a relatively long “loiter” capability was needed and for this (as for their dive bomber), the Rannikkojääkärit looked to their US Marine Advisory and Training Team for advice. Never slow to push the superiority of US aircraft (even when they weren’t) the US Marines pointed the Merivoimat procurement team at the fighters being developed for the US Navy to replace the Grumman F3F biplane. The Merivoimat Air Arm Procurement Team spent a considerable amount of time with the US Navy – they also talked to the British Fleet Air Arm, but considered their procurement to be too restricted by the RAF to be of any use.

While the Merivoimat operated under far different conditions to the US Navy, the basic fighter requirement was similar, with the major difference being that the Merivoimat did not need to operate of Aircraft Carriers and could dispense with much of the carrier-related requirements. As one member of the Merivoimat Procurement Team joked, “the Ahvenanmaa Islands are our aircraft carrier….”

In 1935, the U.S. Navy had issued a requirement for a carrier-based fighter intended to replace the Grumman F3F biplane. The Brewster XF2A-1 monoplane, designed by a team led by Dayton T. Brown, was one of two aircraft designs that were initially considered, together with the Grumma XF4F-1 – a “classic” biplane design with a double-row radial engine. The U.S. Navy competition was re-opened to allow another competitor, the XFNF-1, a navalized Seversky P-35, eliminated early on when the prototype could not reach more than 267 mph (430 km/h). The Brewster XF2A-1 first flew on 2 December 1937 and early test results showed it was far in advance of the Grumman biplane entry (while the XF4F-1 would not enter production, it would later re-emerge as a monoplane, the Wildcat).

The new Brewster fighter had a modern look with a stubby fuselage, mid-set monoplane wings and a host of advanced features. It was all-metal, with flush-riveted, stressed aluminum construction, although control surfaces were still fabric-covered. The XF2A-1 also featured split flaps, a hydraulically-operated retractable main undercarriage (and partially retractable tail wheel), and a streamlined framed canopy. However, the aircraft lacked self-sealing tanks and pilot armor. Fuel was only 160 U.S. gal (606 l), stored in the fuselage. Powered by an 950 hp (708 kW) single-row Wright R-1820-22 Cyclone radial engine, it had an impressive initial climb rate of 2,750 ft/min and a top speed of 277.5 mph (447 km/h), later boosted to 304 mph (489 km/h) at 16,000 ft (4,879 m) after improvements were made to the cowling streamlining and carburetor/oil cooler intakes. With only a single-stage supercharger, high-altitude performance fell off rapidly. Fuselage armament was one fixed .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning machine gun with 200 rounds and one fixed .30 in (7.62 mm) AN Browning machine gun with 600 rounds, both in the nose. The US Navy awarded Brewster Aeronautical Corporation a production contract for 54 aircraft as the F2A-1.

Impressed by the prototype, the Merivoimat signed a statement of intent in December 1937 and concurrent with the US Navy order, ordered 20 of the F2A-1’s early in 1938 at an overall cost of US$1.5 million. The Merivoimat specified compatibility with 87-octane fuel and had the fighters de-navalized – removing all the naval equipment on the fighters, such as their tailhooks and life-raft containers, resulting in a somewhat lighter aircraft. The Finnish F2A-1s also lacked self-sealing fuel tanks and cockpit armor. After delivery to Finland, the Merivoimat Air Arm added armored backrests for the pilots, metric flight instruments, the Finnish Väisälä T.h.m.40 gunsight, and four .50 in (12.7 mm) machine guns. The top speed of the Finnish Buffalos, as modified, was 297 mph.

Service testing of the XF2A-1 prototype began in January 1938 (testing in which a Merivoimat Air Arm evaluation team participated) and in June, production started on the F2A-1. They were powered by the 940 hp (701 kW) Wright R-1820-34 engine and had a larger fin. The added weight of two additional .50 in (12.7 mm) Browning wing guns and other equipment specified by the Navy for combat operations reduced the initial rate of climb to 2,600 ft/min. Plagued by production difficulties, Brewster delivered all aircraft ordered by the Merivoimat but only delivered 11 F2A-1 aircraft to the US Navy (the remainder of the order was diverted to Finland in modified form to fill the additional Finnish order place in mid-1938).

The Buffalo fighter was never referred to as the “Buffalo” in Finland; it was known simply as the “Brewster” or sometimes by the nicknames Taivaan Helmi (“Sky Pearl”) or Pohjoisten Taivaiden Helmi (“Pearl of the Northern Skies”). Other nicknames were Pylly-Valtteri (“Butt-Walter”), Amerikanrauta (“American hardware” or “American car”) and Lentävä Kaljapullo (“flying beer-bottle”). In Merivoimat service, the Buffalos were regarded as being very easy to fly, a “gentleman’s plane”. The Buffalo was also popular because of their relatively long range and flight endurance, and also because of their low-trouble maintenance record. This was in part due to the efforts of the Finnish engine mechanics who solved a problem that plagued the Wright Cyclone engine simply by inverting one of the piston rings in each cylinder. This had a positive effect on engine reliability. The cooler weather of Finland was also a plus for the engine. In the end, the Brewster Buffalo gained a reputation in Finnish service as one of their more successful fighter aircraft.

The 1938 Procurement Program had made provision for a second fighter squadron for the Merivoimat Air Arm and in April 1938, an order for a further 20 Buffalos was placed. Manufacturing for the Meroivoimat order for 40 aircraft began in June 1938 and the aircraft were shipped in November 1938, arriving in Turku December 1938 and entering service between January-March 1939. Payment for the aircraft was made from the thirty million US Dollar loan negotiated in 1937 with the overall cost of the two orders amounting to some US$3.5 million. All 40 Buffalo fighters were in service with the Merivoimat Air Arm on the outbreak of the Winter War.

And after the actual outbreak of the Winter War on 30 November 1939, Finland worked furiously to acquire additional aircraft. On 16 December 1939, Finland signed a contract for the provision of a further 44 Model 239 fighters. The total price to be paid was US $3.4 million, and the deal included the provision of spare parts, 10 replacement engines and 20 Hamilton Standard propellers. These 44 Buffalos were fitted with the new 1,200 hp (895 kW) Wright R-1820-40 engines giving a maximum speed of 323mph and again, were stripped down and de-navalized for Finland. The aircraft were diverted from an order for the US Navy – who protested but who were overruled in this instance by Roosevelt. Built in four batches, the Brewster Buffalos were loaded aboard four merchant ships in New York and shipped for Bergen, in Norway, arriving in January-February 1940. The crates with the fighter were sent by railway to Sweden and assembled by SAAB, near Gothenburg. By April 1940, all 44 Buffalos had been assembled, flight tested and were in service with the Ilmavoimat in time for the May 1940 Spring Offensive, where they had their baptism of fire in combat.

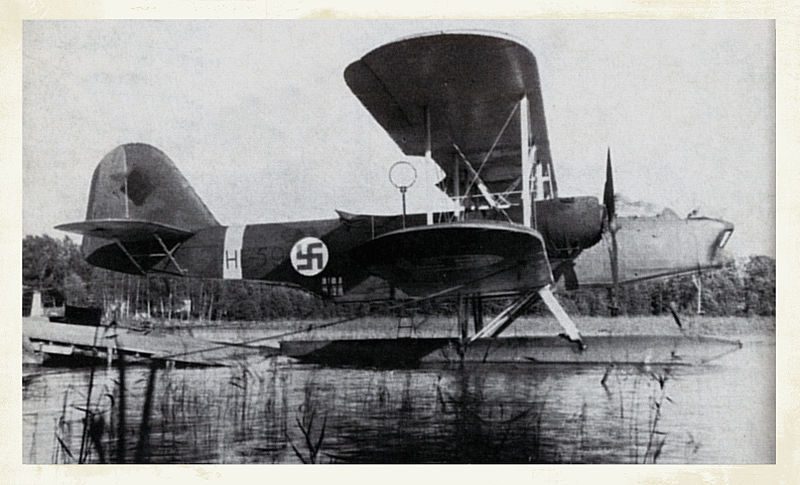

Heinkel He59 Maritime Aircraft – ordered early 1937

The Merivoimat Air Arm purchased 10 of these aircraft in early 1937 to use as a light transport and SAR aircraft. During the Winter War they were also used at times to ferry long range reconnaissance patrols behind enemy lines and to retrieve them.

The Heinkel He 59 was a German military aircraft designed in 1930 resulting from a requirement for a torpedo bomber and reconnaissance warplane able to operate with equal facility on wheeled landing gear or twin-floats. In 1930, Ernst Heinkel began developing an aircraft for the German Navy. To conceal the true military intentions, the aircraft was officially a civil aircraft. The He 59B landplane prototype was the first to fly, an event that took place in September 1931, but it was the He 59A floatplane prototype that paved the way for the He 59B initial production model, of which 142 were delivered in three variants. The Heinkel He 59 was a pleasant aircraft to fly; deficiencies noted were the weak engines (2× BMW VI 6.0 ZU water-cooled V12 engines, 660 hp each), the limited range, the small load capability and insufficient armament (Two or three machine guns).

The He 59B-2 was a four-seat mixed-structured twin-engined bi-plane maritime aircraft.. The wings were made of a two-beam wooden frame, where the front was covered with plywood and the rest of the wing was covered with fabric. The box-shaped fuselage had a fabric covered steel frame. The tail section was covered with lightweight metal sheets. The keels of the floats were used as fuel tanks – each one holding 900 liters of fuel. Together with the internal fuel tank the aircraft could hold a total of 2,700 liters of fuel. Two extra fuel tanks could also be placed in the bomb bay, bringing the total fuel capacity up to 3,200 liters. The propeller was fixed-pitch with four blades. With a crew of three, a speed of 146mph, a combat range of only 466 miles, a ferry range of 1,175 miles, and a service ceiling of only 16,400 feet, performance was limited. The aircraft could carry 4 × 250 kg (550 lb) bombs or 1 × 800 kg (1,760 lb) torpedo or 4 × 500 kg (1,100 lb) mines. Alternatively, 6-8 passengers could be carried.

Merivoimat Dive Bomber – Vought SB2U Vindicator – 20 ordered in late 1937

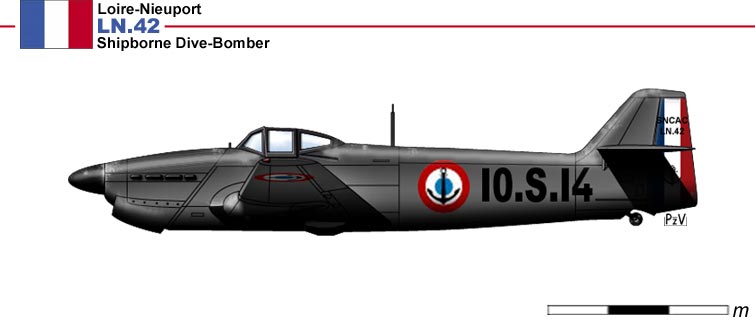

In their search for a Dive Bomber to equip a single Merivoimat Dive Bomber Squadron in 1937, the Procurement Team evaluated a number of different aircraft before making a decision. Among these were the American Vought SB2U Vindicator, Northrop BT, Curtiss SBC-3 Helldiver, Brewster SBA and Grumman SBF, the British Blackburn Skua and Hawker Henley, the French Loire-Nieuport LN 410, the German Ju87 and the Italian Breda BA-65 ground attack fighter. The overall evaluatuion and flight testing program was lengthy, with a decision not reached quickly and an order was placed only shortly before the end of the year. And eventually, as with other purchasing decisions made in 1937, the final and major influencing factor was the sizable US loan that had been made available in 1937.

Vought SB2U Vindicator

The Vought SB2U Vindicator was a carrier-based dive bomber developed for the United States Navy in the 1930s, the first monoplane in this role. In 1934, the United States Navy issued a requirement for a new Scout Bomber for carrier use, and received proposals from six manufacturers. The specification was issued in two parts, one for a monoplane, and one for a biplane. Vought submitted designs in both categories, which would become the XSB2U-1 and XSB3U-1 respectively. The biplane was considered alongside the monoplane design as a “hedge” against the U.S. Navy’s reluctance to pursue the modern configuration.

The Vought SB3U-1 Corsair was a two seat, all metal biplane dive bomber built by Vought Aircraft Company of Dallas, Texas for the US Navy. The aircraft was equipped with a closed cockpit, had fixed landing gear, and was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 radial air-cooled engine. The SBU-1 completed flight tests in 1934 and went into production under a contract awarded in January 1935, with 125 being built. The Corsair was the first aircraft of its type, a scout bomber, to fly faster than 200 mph. Maximum speed was 205mph, range was 548 miles and armament consisted of 1x Fixed forward firing .30 in (7.62 mm) Browning machine gun and 1x machine gun flexibly mounted .30 in machine gun in rear cockpit and 1 x 500lb bomb. This aircraft was not evaluated by the Ilmavoimat – introduced into service in 1935, by 1937 it was already outdated.

By way of contrast, the Vought XSB2U-1 was a conventional low-wing monoplane configuration, with a retractable tailwheel undercarriage and the pilot and tail gunner seated in tandem under a long greenhouse-style canopy. The fuselage was of steel tube construction, covered with aluminum panels from the nose to the rear cockpit, and with a fabric covered rear fuselage, while the folding cantilever wing was almost completely fabric except for a metal leading edge. A 700hp Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin-Wasp Junior radial engine drove a two-blade constant-speed propeller, which was intended to act as a dive-brake during a dive bombing attack. A single 1,000 lb (450 kg) bomb could be carried on a swinging trapeze to allow it to clear the propeller in a steep dive, while further bombs could be carried under the wings to give a maximum bombload of 1,500 lb (680 kg).

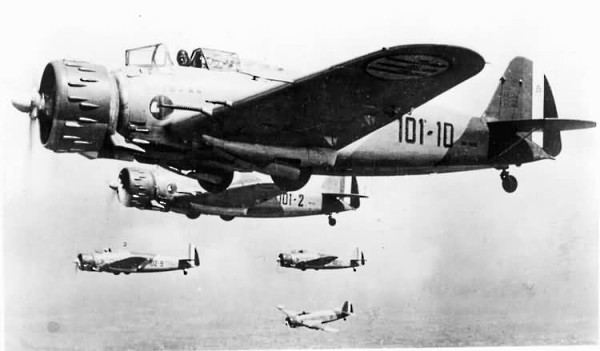

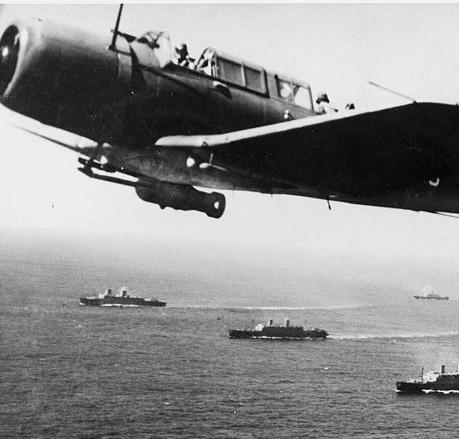

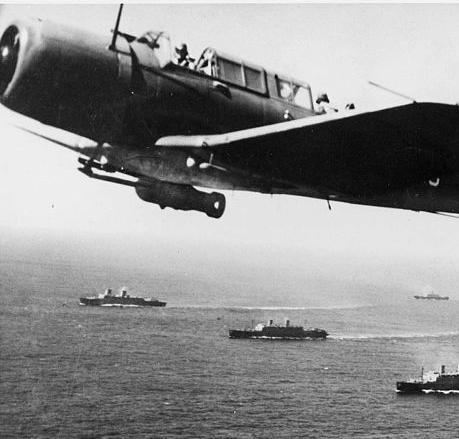

Merivoimat Vought Vindicator escorting ships of the Helsinki Convoy through the Baltic north of Gotland, Spring 1940

Designated XSB2U-1, one prototype was ordered by the US Navy on 15 October 1934 and was delivered on 15 April 1936. Accepted for operational evaluation on 2 July 1936, the prototype XSB2U-1, BuNo 9725, crashed on 20 August 1936. During the Navy tests a number of problems were uncovered. It had been intended to equip the aircraft with a reversible propeller to act as a dive brake; however, this proved to be difficult to use and became technically unsatisfactory. As a replacement, Vought constructed a dive flap that consisted of a number of finger-like spars mounted near the wing leading edge that, during normal flight, were flush with the wing surface but during a dive could be extended at right angles to the wing surface to slow the aircraft. These flaps failed to work satisfactorily because they caused so much drag that full engine power was needed to maintain control. Additionally, the flaps caused severe aileron buffeting, and weighed some 140 pounds. As a result, the Navy decided to adopt a shallower dive angle and to extend the landing gear to act as a form of dive brake. The prototype was also modified to include additional bracing on the pilots and observers canopies. The successful completion of trials led to an initial order for 54 aircraft from the US Navy in October 1936.

The Ilmavoimat evaluated the Vindicator early in 1937. While they rated the aircraft highly, the Procurement Team went on to evaluate a number of other Dive Bombers before reaching a final decision to purchase the Vindicator in late 1937. An order was placed for 20 of the aircraft. Delivery took place in June 1938 and the Vindicators entered service shortly thereafter.

With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner) and powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1535-96 Twin Wasp Jr radial engine of 825 hp (616 kW), the Merivoimat Vindicators had a maxiumum speed of 251mph. Additional fuel tanks were added after delivery, increasing the range from 630 miles to some 800 miles and a service ceiling of 27,500 feet. The Merivoimat version was armed with four forward firing machineguns in the wings and one machinegun in a flexible mount for the rear-facing gunner. Bombload consisted of one 1,000lb or one 500lb bomb.

Within the US Navy, the Vindicator was by now well-tried and popular. However, by late 1938 it was beginning to be phased out as the new Douglas SBD Dauntless aircraft began to be delivered. Both the US Navy and Vought were wondering what to do with the surplus Vindicators. This was opportune for Finland. Early in 1939, with the threat of war with the USSR increasingly a risk and the deteriorating European situation, the Finnish Finance Minister, Risto Ryto, had negotiated a further loan from the USA (although not in the same ballpark as the 1937 $30 million amount) and additional war supplies were being purchased whereever they were available.

Vought Vindicators ordered for France, resold to the British and then side-tracked for urgent delivery to Finland in June 1940…..they entered service with the Merivoimat Air Arm in September 1940 and saw little or no action.

Among these purchases were a further 20 US Navy surplus Vindicators. These were well-used, but as second hand aircraft the cost was significantly reduced and they were shipped to Finland in summer 1939, along with a number of other second hand aircraft that had been purchased (these will be covered when we get to cover 1939 and the Emergency Procurement Program of that year, which was allocated some 45% of all Finnish State spending, significantly reducing funding for every other government program, albiet with some major but as it proved, short-lived, political fallout).

In the event, the ex-US Navy Vindicators arrived in August 1939 and had not yet even been repainted as the Winter War broke out. Still with their US markings in many cases, they were pressed into service immediately – such was the tempo of operations that some of these aircraft were not reflagged until March 1940 – something which led to accusations from the USSR that US forces were assisting Finland.

Another and later source of supply were Vindicators that had been ordered for the French Air Force. The V156 (the export version of the Vindicator) was shown at the Paris Air Show in November 1938 and French interest had been aroused. The French Government decided in May 1938 to order ninety Vindicators as their own dive bomber program was falling apart. The first five were delivered to Orly in July 1939 and more were on the way as WW2 broke out. Some forty in all were delivered before Franch fell to the German onslaught. Circumventing the US Neutrality legislation, a further thirty Vindicators from the remaining French order, which had been already been repainted for sale to the UK, were reallocated to Finland and shipped to Petsamo in June 1940, entering service only in the final month of the Winter War where they saw little action.

Northrop BT

The Northrop BT was a two seat, single engine, monoplane, dive bomber built by the Northrop Corporation for the United States Navy at a time when Northrop was a subsidiary of the Douglas Aircraft Company. The design of the initial version began in 1935.

The Northrop XBT-1 had been entered in the competition as a combination dive bomber/scout aircraft and the Navy decided to develop the design as a dive bomber. The first prototype was powered by a 700 hp (522 kW) Pratt and Whitney XR-1535-66 Twin Wasp Jr. double row, radial air-cooled engine. The aircraft had slotted flaps and a landing gear that partially retracted. The next iteration of the BT, designated the XBT-1 was equipped with a 750 hp (559 kW) R-1535 engine. This aircraft was followed in 1936 by the BT-1 that was powered by an 825 hp Pratt and Whitney R-1535-94 engine. One of the BT-1 aircraft was modified with a fixed tricycle landing gear and was the first such aircraft to land on an aircraft carrier.

The Ilmavoimat/Merivoimat team evaluated the BT-1 in early 1937, but at this stage the prototype was undergoing a redesign to address issues indentified in testing.The aircraft was eliminated from consideration at this point, although it was agreed that it would be reevaluated following completion of the next version prototype. The final variant, the XBT-2, was a BT-1 aircraft modified to incorporate a fully retracting landing gear, wing slots, a redesigned canopy, and was powered by an 800 hp (597 kW) Wright XR-1820-32 radial air-cooled engine. The XBT-2 first flew on 25 April 1938 and after testing the US Navy placed an order for 144 aircraft. In 1939 the aircraft designation was changed to the Douglas SBD-1 with the last 87 on order completed as SBD-2s. The Northrop Corporation had become the El Segundo division of Douglas aircraft hence the change to Douglas. The U.S. Navy placed an order for 54 BT-1s in 1936 with the aircraft entering service during 1938. The BT-1s served on the USS Yorktown and Enterprise. The type was not a success in service due to poor handling characteristics, especially at low speeds, “a fatal flaw in a carrier based aircraft.” It was also prone to unexpected rolls and a number of aircraft were lost in crashes.

With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner), the BT-1 was powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1535-94 Twin Wasp Jr. double row radial air-cooled engine of 825 hp (615 kW), giving a maximum speed of 222mph with a range of 1,150 miles and a service ceiling of 25,300 feet. Armament consisted of one forward and one rear-facing machinegun and a 1,000lb bomb carried under the fuselage.

Curtiss SBC-3 Helldiver

The Curtiss SBC Helldiver was a two-place scout bomber built by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. It was the last military biplane procured by the United States Navy. In 1932, the U.S. Navy gave Curtiss a contract to design a parasol two-seat monoplane with retractable undercarriage and powered by a Wright R-1510 Whirlwind, intended to be used as a carrier-based fighter. The resulting aircraft, designated the XF12C-1, flew in 1933. Its chosen role was changed first to a scout, and then to a scout-bomber (being redesignated XS4C-1 and XSBC-1 respectively), but the XSBC-1’s parasol wing was unsuitable for dive bombing. A revised design was produced for a biplane, with the prototype, designated the XSBC-2, first flying on 9 December 1935.

The SBC-3 was the initial production model and was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior. The SBC-3 began operational service in 1938. A total of 83 SBC-3s were built. The SBC-4 was powered by a Wright R-1820 Cyclone. The SBC-4 entered service in 1939 with 174 SBC-4s in all being built. The US Navy took deliveries of the new aircraft in mid-1937 with the first batch of carrier-based aircraft going to the Yorktown, but time and technology caught up to the advanced biplane. The Finnish procurement team evaluated and tested a prototype aircraft in early 1937 but even at that stage, before it had enetered service, considered it an outdated design with inadequate performance. It was crossed off the list.

In US service, the SBC-4 was soon relegated to hack duties and service as an advanced trainer for training units in Florida. Within the US Navy, the SBC Helldiver was not destined to have a long U.S. service life, but its impact was felt as the type made a lasting contribution by serving as the key platform in developing dive bombing tactics and honing aircrew skills crucial to winning the war in the Pacific.The last aircraft was stricken from the Navy roster in October 1944. Aware of the use being made of the SBC-4 Helldivers in early 1939 on hack duties and service as an advanced trainer, the Finnish Procurement Team in Washington DC pressed the US to sell these to Finland as a matter of urgency, even going so far as to have the Finnish Ambassador in the US directly raise the matter with President Roosevelt. However, in this instance nothing successful was achieved and in the end some 50 SBC-4s were delivered to the French Navy. The 50 SBC-4s delivered to France were actually aircraft already in service with the United States Navy.

The Curtiss SBC Helldiver Biplabe had a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner), was powered by a single Wright R-1820-34 radial engine of 850 hp (634 kW) with a maximum speed of 234mph, a range of 405 miles and a service ceiling of 24,000 feet. Armament consisted of two machineguns (one forward facing, one rear) and one 1,000lb bomb.

On 6 June 1940, Naval reservists received orders to immediately fly 50 SBC-4’s to the Curtiss factory at Buffalo, New York. At Buffalo, a Bureau of Aeronautics inspector informed the pilots their aircraft were to be flown to Halifax, Nova Scotia to be loaded aboard the French aircraft carrier Béarn. From Buffalo to Halifax, the reserve pilots were officially employees of Curtiss. Curtiss paid each pilot $250 plus return rail fare from Halifax to Buffalo. All navy insignia were removed from their uniforms or taped over. Upon return to Buffalo, the pilots went back on Navy orders for return to their home bases. Curtiss employees worked overtime to remove and replace all gear and instruments marked BUAERO, BUSHIPS or BUORD. The Navy .30 in (7.62 mm) machine guns were replaced by .50 in (12.7 mm) guns and the aircraft were repainted in camouflage colors with the French tricolor on the rudders. The hasty conversion did not allow time for adequate checkout of replacement instruments. Weather deteriorated with rain and fog over most of the route from Buffalo to Halifax. The Bureau of Aeronautics inspector temporarily halted flights after one of the first pilots was killed in a crash between Buffalo and Albany.

When the weather improved, sections of three aircraft were dispatched from Buffalo Houlton, Maine. After landing at Houlton, the aircraft were towed down a road across the Canadian border for takeoff from a New Brunswick farm pasture to avoid legal implications of flying over the border. The surviving 49 aircraft flew over the Bay of Fundy and 44 of them were loaded aboard Béarn at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia together with 21 P-36 Hawk fighters and 25 Stinson 105’s for the French Armée de l’Air and five Brewster Buffalos for Belgium. France surrendered while Béarn was crossing the Atlantic; she turned south to Martinique, where the SBC-4s corroded in the humid Caribbean climate while waiting on a hillside near Fort-de-France. The five SBC-4s remaining in Canada when France surrendered were taken over by the United Kingdom and were used as ground-instructional airframes. Nothing practical was gained, and Finland missed out on what could have been a reasonably adequate ground attack aircraft. Fortunately, other aircraft were available and it was not a critical loss.

Brewster SBA

The SBN was a United States three-place mid-wing monoplane scout bomber/torpedo aircraft designed by the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation and built under license by the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The United States Navy issued a specification for a scout-bomber in 1934 and the competition was won by Brewster. One prototype designated the XSBA-1 was ordered on October 15, 1934. The prototype first flew on April 15, 1936, and was delivered to the Navy for testing. Some minor problems were found during testing and the aircraft was given a more powerful engine.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation identified the production bottleneck issues with this aircraft and despite the promising performance of the prototype, it was eliminated from the shortlist as a result. Events proved this to be a correct decision.

With a Crew of 3 (Pilot, Navigator, Gunner), a single Wright XR-1820-22 Cyclone radial engine of 950 hp (709 kW) giving a maximum speed of 254 mph, a range of 1015 miles, a service ceiling of 28,300 feet and armed with one rearward firing machinegun, the SBN carried up to 500lb of bombs.

Because of the pressures of producing and developing the Brewster F2A the company was unable to produce the aircraft and the Navy acquired a license to produce the aircraft itself at the Naval Aircraft Factory. In September 1938 the Navy placed an order for 30 production aircraft. Due to pressures of work at the NAF it did not deliver the first aircraft, now designated the SBN, until 1941 and the remaining aircraft were delivered between June 1941 and March 1942.

Grumman SBF

In late 1934, the U.S. Navy’s Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) issued a specification for new scout and torpedo bomber designs. Eight companies submitted 10 designs in response, evenly split between monoplanes and biplanes. Grumman, having successfully provided the FF and F2F fighters to the Navy, along with the SF scout, submitted an advanced development of the SF-2 in response to the specification’s request for a 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) aircraft capable of carrying a 500 lb (230 kg) bomb. Given the model number G-14 by Grumman, the aircraft received the official designation XSBF-1 by the Navy, and a contract for a single prototype was issued in March 1935.

With a Crew of 2, the Grumman SBF had a maximum speed of 215mph, a range of 525 miles and a service ceiling of 26,000 feet. Amed with two machineguns (one forward-firing, one rear-facing, it could carry up to a 500lb bombload

The XSBF-1 was a two-seat biplane, featuring an enclosed cockpit, a fuselage of all-metal construction, and wings covered largely with fabric. Power was provided by a 650 hp (480 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior air-cooled radial engine driving with a variable-pitch propeller. Armament was planned to be two .30 in (7.62 mm) forward-firing M1919 Browning machine guns, one of which could be replaced by a .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning; the prototype carried only a single gun. A single .30 in weapon was fitted in the rear cockpit for defense, and one 500 lb (230 kg) bomb was to be carried in a launching cradle under the fuselage. The arrestor hook was carried in a fully enclosed position, while flotation bags were fitted in the wings in case the aircraft was forced to ditch. The landing gear of the XSBF-1 was similar to that of the F3F fighter.

The XSBF-1—piloted by test pilot Bud Gillies—flew for the first time on December 24, 1935. Following initial testing, which found the aircraft to be reasonably faultless, the XSBF-1 was delivered to the U.S. Navy for evaluation in competition with two other biplanes submitted to the 1934 specification, the Great Lakes XB2G and the Curtiss XSBC-3. Unusually for biplanes, all three types possessed retractable landing gear. The evaluation showed that the design from Curtiss was superior to the Grumman and Great Lakes designs, and an order was placed for the Curtiss type, designated SBC-3 Helldiver in service, in August 1936.

Given the US rejection of the aircraft, the Ilmavoimats evaluation of the prototype was cursory at best – it had been assigned to the Naval Air Station at Anacostia where it was being used for continued testing and as a hack aircraft.

Blackburn Skua – evaluated 1937

The Blackburn B-24 Skua was a carrier-based low-wing, two-seater, single-radial engine aircraft operated by the British Fleet Air Arm which combined the functions of a dive bomber and fighter. Built to Air Ministry specification O.27/34, it was a low-wing monoplane of all-metal (duralumin) construction with a retractable undercarriage and enclosed cockpit. It was the Fleet Air Arm’s first service monoplane, and was a radical departure for a service that was primarily equipped with open-cockpit biplanes such as the Fairey Swordfish. Performance for the fighter role was compromised by the aircraft’s bulk and lack of power, resulting in a relatively low speed; the contemporary marks of Messerschmitt Bf 109 made 290 mph (467 km/h) at sea level over the Skua’s 225 mph (362 km/h). However, the aircraft’s armament of four fixed, forward-firing 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns in the wings and a single flexible, rearward-firing Lewis .303 in (7.7 mm) machine gun was effective for the time (although whenever possible the gunner would try to replace this with a Vickers “K” gun which was more reliable and had a higher rate of fire).

For the dive-bombing role, a single 250 lb (110 kg) or 500 lb (230 kg) bomb was carried on a special swinging crutch under the fuselage, which enabled the bomb to clear the propeller arc on release. Four 40 lb (20 kg) bombs or eight 20 lb (9 kg) Cooper bombs could also be carried in racks under each wing. The 500lb AP and SAP bomb was only used against armoured warships, for attacks on merchant ships and ground targets the normal bombload was a 250 lb bomb in the fuselage recess and either 20lb or 40lb bombs on the light series carriers. The 250 lb bomb had only a little less explosive content than the 500lb SAP and AP bombs (the extra weight of the latter was down to the casing, needed to punch through armour). If used against ground targets the SAP and AP bombs would often bury themselves deep before exploding, reducing the blast effect. The small and largely ineffective 100 lb anti-submarine (AS) bomb could also be carried in the fuselage recess.

Powered by a Bristol Perseus XII nine cylinder, sleeve valve, air cooled radial engine rated at 815 hp, the Skua had a maximum speed of 225mph, a service ceiling of 20,500 ft (reached in 43 mins – the Skua had a very poor rate of climb) and maximum range of some 760 miles (an endurance of over 4 hours). It had large Zap-type air brakes/flaps which helped both in dive bombing and landing on aircraft carriers at sea.

The first prototype Skua had problems with stability and it and the second prototype (both known as Skua MK Is) had to be modified with a longer nose and upturned wingtips, features carried over to the production aircraft (known as Skua Mk IIs). The spin characteristics of the Skua were bad enough to prompt the fitting of an anti-spin parachute in the tail to aid recovery. Interestingly, the Skua was designed with a very specific task in mind, the sinking of enemy aircraft carriers, for which its single 500 lb bomb would have been more than adequate (only Britain developed and deployed aircraft carriers with armoured decks during World War II). The role of fighter was intended as secondary. In combat however the Skua was forced to be used as a fighter much more often than as a dive bomber. Its performance as a fighter was often better than might be imagined just by looking at its modest speed in level flight. Its long endurance also meant it could loiter at altitude (once it got there, it had a very poor rate of climb) and dive onto its victims. Where the Skua had the potential to be badly misused was in attacks against heavily armoured warships, where its 500 lb bomb would cause little damage.

Two prototypes were ordered in 1935 with the first prototype (K5178) flying nearly two years later on 9th Feb 1937. It was this first prototype that the Ilmavoimat evaluated in mid-1937. While the test pilots liked the Skua’s handling, the aircraft could only carry half the bombload of the Vindicator (which was the leading choice at this stage), was slower and had less range. The Ilmavoimat decided at this stage to eliminate the Skua from consideration but to revisit the aircraft after it entered production.

In the UK, in October of 1937 the first prototype went on to handling trials at A.&A.E.E. Martlesham. The second prototype (K5179) did not fly until 4th May 1938, and the first production Skua (L2867) flew on 28th August 1938. A total of 190 Skuas had been ordered as far back as July 1936, even before the first prototype had flown. Thus production was started a full two years after the order. However deliveries were prompt after that and over 150 had been delivered by the time WW2 started, with all but one being delivered by the end of 1939. This meant that the Skua was very much a “new” aircraft when it first went to war and its pilots were still finding their way in this big metal monoplane aircraft with its retractable undercarriage and enclosed cockpits, all a novelty to British carrier pilots of the time. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened if the original expected “in-service” date of 1937 had been kept to. Then the crews would have had two years to get to know their aircraft and the Navy would probably have had 4 or 5 fully equipped and trained Skua Squadrons “ready to go” at the outbreak of war.

One further weakness of the Skua was that, as delivered to the British Fleet Air Arm, the Skua’s only means of radio communication was by Morse code back to the carrier. There was no speech-based radio communication with the carrier and not even Morse code communication with other Skuas. This meant communication between aircraft was limited to hand-signals or Aldis-lamp. This must have severely limited the ability of the Skua crews to co-operate, particularly in the fighter role – No “Tally Ho Red Leader, bandits 9 o’clock low” for the poor Skua pilots!

Hawker Henley